Mon, Jul 14, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 3, Issue 1 (Winter 2017 -- 2017)

JCCNC 2017, 3(1): 3-10 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abdulla Karim M, Rafii F, Nikbakht Nasrabadi A. Kurdistan Nurses’ Feelings and Experiences About Patients’ Death in ICUs: A Case Study in Kurdistan Region, Iraq. JCCNC 2017; 3 (1) :3-10

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-122-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-122-en.html

1- Head of Continuous Professional Development, General Directorate of Erbil Health, Ministry of Health, Kurdistan Region Iraq, Iraq.

2- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,rafiee.f@iums.ac.ir

3- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 568 kb]

(1575 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5696 Views)

Full-Text: (1616 Views)

1. Background

Death of a patient generally creates a great deal of pain and grief in nurses providing care (Oberle & Hughes 2001). The recurrent nature of these events affects the nurses confidence to perform their duties and results in dissatisfaction with their work (Carlson & Bultz 2003). Intensive Care Units (ICUs) of hospitals are designed to provide care for critically ill patients (Kongsuwan et al. 2010). Such patients are transferred to ICUs to receive advanced care using sophisticated medical technologies, with the aim of prolonging their life expectancy (Williams et al. 2003). However, even with the critical care which provides in ICU, dying of some patients is inevitable which in turn affects the nurses more than other health care team and could be attributed to the relationship that has formed during caring encounters among the nurse, patient and his or her relatives (Valiee, Negarandeh & Dehghan Nayeri 2012).

Patients in the ICU are cared for and monitored very carefully by a group of health care experts, including nurses (Dunn, Otten & Stephens 2005). During their ICU stay, patients receive constant specialized and critical care from the nursing staff (Hov, Hedelin & Athlin 2007). ICU nurses are commonly trained to cope with any unusual situation that may arise in the ICU (Prompahakul & Nilmanat 2011). Although the main emphasis of health care provision in the ICU is on recovery, many patients still die, at an estimated rate of one out of five admissions (Frommelt 2003). Nevertheless, nurses perform a variety of activities aiming at recovering and preserving physical and psychological integrity of both patients and their family members (Thacker 2008). As a result, many nurses working in ICUs experience a great deal of pain and pressure by the stress they experience from caring for these patients (Rafii, Nikbakht Nasrabadi & Karim 2015).

The ICU environment is generally stressful or emotionally distressing for not only nurses, but also patients and their family members (Hays 2006). Moreover nurses by providing medical care, develop a sympathetic relationship with the seriously diseased or terminally ill patients (Valiee, Negarandeh & Dehghan Nayeri 2012). While performing such critical duties, nursing staff face many challenges in the ICUs (Espinosa et al. 2010). For instance, unwelcome circumstances and conflicts may happen between nurses, physicians, and patients’ families. However, nursing staff are expected to overcome these barriers and remain attentive when caring for critically ill patients (Kirchhoff 2000). Also, inadequate documentation exerts a negative impact on quality care for terminally ill patients; because some patients may receive insufficient treatment due to late recognition of the deterioration, poor documentation, and unsuitable communication (Nelson-Marten, Braaten & English 2001).

While most patients and their families expect greater care in the ICU, shortage of well-trained nurses prevents the provision of standard medical care

(Beckstrand, Callister & Kirchhoff 2006). According to Hansen et al. (2009), provision of effective and advanced care to terminally ill patients requires high levels of knowledge and skill. Moreover, many studies have emphasized on a positive relationship between nurse’s educational level and self-awareness, along with a better delivery of patient’s care (Emami & Nasrabadi 2007). In general, nurses are required to undergo tailored courses to become qualified as an ICU attendant. However, there are no such available training courses in Kurdistan (Moore et al. 2004). Also, study conducted by Salih et al. (2014), reports that Kurdish nurses with qualification regarding ICU provide better care than those who lack relevant education. While some nurses perceive end-of-life care in ICU as an effective and compassionate experience (Beckstrand & Kirchhoff 2005), others feel perplexity, despair, and frustration as reported by nurses in the neuroscience ICU (Calvin, Kite-Powell & Hickey 2007). However, Valiee et al. (2012) concluded that one could barely find pleasure in a workplace where suffering is a constant norm. Accordingly, both pleasure and suffering should be considered in studying Kurdish nurses who work in ICU to be able to find out their feelings and giving proper recommendations.Hence, the present study attempts to explore the feelings and experiences of Kurdish ICU nurses who care for dying patients in the cultural context of Kurdistan Region, Iraq. The outcome of this study would provide evidence on the impact of feelings on the role played by ICU nurses.

2. Materials & Methods

Study design

Kurdish nurses’ feelings and experiences regarding their care for dying patients in the ICU were explored using an inductive content analysis approach (Lichtman 2012).

Participants

A purposive sample of 10 eligible ICU nurses working in Rezgary Teaching Hospital and Hawler Teaching Hospital were recruited with prior approval of the related hospital managers. The inclusion criteria for participation in this study were as follows: 1) being Kurdish registered nurses working in ICUs in Erbil City, 2) having cared for at least three critically ill adult patients, 3) having at least 2 years of ICU experience, and 4) willing to participate in the study.

The participants were five males and five females and their age ranged from 26 to 35 years, with the mean age of 30 years. While seven participants held a BS in nursing, the other three had a diploma in nursing. Years of experience of working in ICU ranged from 4 to 12 years, with a mean of 6 years. During an initial phone call with potential participants, they were provided with detailed description of the study and its risks and benefits, confidentiality of data, and the informed consent procedures.

Data collection

Data were collected through in-depth semi-structured individual interviews. Before the interviews, the study objectives were explained and the participants’ questions and concerns were answered and considered. Individual face-to-face interviews were performed in local language (Kurdish). The participants were asked to describe their feelings and experiences when working in the ICU and subsequent questions were framed around their responses. Follow-up questions were then posed to encourage the participants to further explain their perceptions. These questions included “What feelings make you suffer when working in the ICU?”, “How do you tackle these feelings?”, “What encourages you to continue working in the ICU?”, “How does caring for different patients differ?”, “Can you explain more?”, “Can you give me an example?”, “How did you feel/think about that?”, “What was it like?”, and “You mean ...?” For a better understanding, the interviewer sometimes remained silent as a tactful way to prompt the participants to recall and describe their experiences. The participants were also asked to elaborate on any other aspects which were not covered by interview questions. The interviews were tape recorded and immediately transcribed and analyzed. Each interview lasted 30-60 minutes. The interviews continued until data saturation.

Data analysis

To investigate the feelings and experiences of Kurdish nurses regarding their care for dying patients in the ICU, the qualitative content analysis method was employed (Lichtman 2012). To meet this goal, first the obtained data were translated into English line by line and word by word by a native bilingual person and then inductive content analysis was performed on the transcribed interviews as suggested by Elo and Kyngäs (2008). Accordingly, the first stage of inductive content analysis was open coding during which the transcriptions were read, notes were taken, and the headings were marked in the margin of the text. The headings and categories were created freely to portray all aspects of the provided content. In the second stage, i.e. creating categories, the interviews were reread several times and similar headings were merged to reduce the number of categories and creation of broader categories. The last stage, i.e., abstraction, involved the formulization of a hierarchy for the developed categories. All categories and their subcategories were named based on their lexical content. The highest possible level of abstraction was sought in this process (Elo & Kyngäs 2008).

Trustworthiness

In all qualitative approaches, including content analysis method, trustworthiness is a measure of the level of soundness or adequacy of a research method (Elo & Kyngäs 2008; Holloway & Wheeler 2010). Therefore, when performing a content analysis, the researchers need to accurately describe data analysis procedures and justify the reliability of the results (Elo & Kyngäs 2008). In an attempt to ensure trustworthiness, we determined appropriate times and places for the interviews, tried to win the participants’ trust and establish good relationships with them, benefited from the complementary opinions of our colleagues, and reviewed the handwritten texts. The transcriptions and the extracted codes were checked by two professors. Moreover, the PhD candidate who conducted the interviews had worked in Kurdistan and had relevant experience in critical care nursing.

Ethical considerations

The research project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Before the recruitment of the nurses, prospective participants were called and provided with details on the objectives, risks, and advantages of the study, confidentiality of data, the voluntary nature of participation, and their right to withdraw at any time. In addition upon the recruitment of each nurse, an informed consent was received and before each interview the permission to record was also obtained. During the transcription of interviews, the names of all participants were changed into codes to ensure anonymity. Moreover, the recorded interviews and transcriptions were kept in a safe place.

3. Results

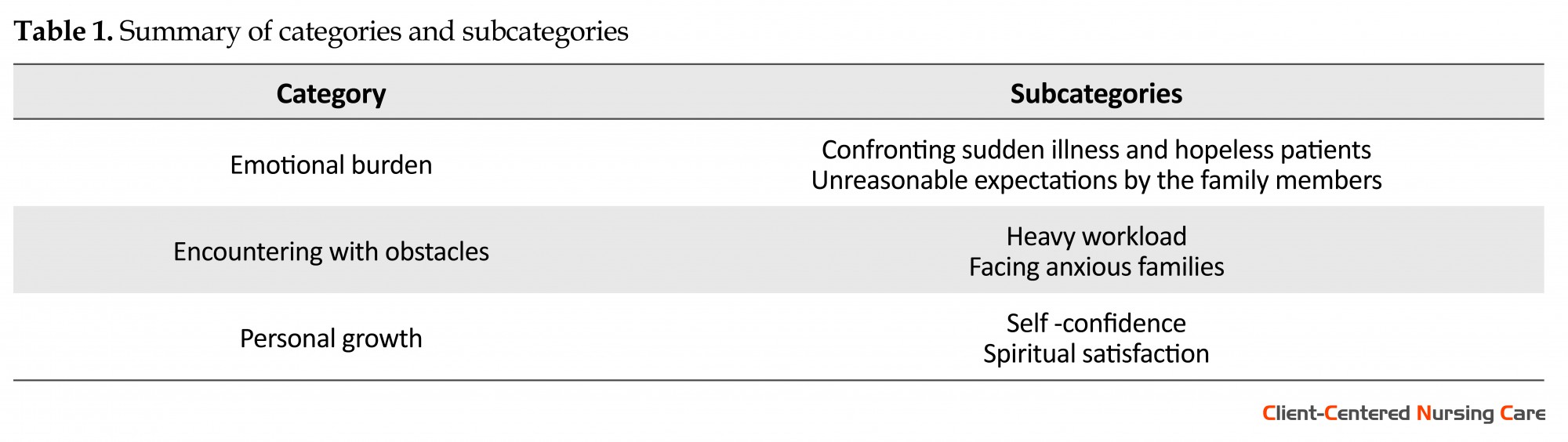

After data analysis, three main categories, including emotional burden, encountering with obstacles, and personal growth emerged. Each category comprised a number of subcategories (Table 1).

Death of a patient generally creates a great deal of pain and grief in nurses providing care (Oberle & Hughes 2001). The recurrent nature of these events affects the nurses confidence to perform their duties and results in dissatisfaction with their work (Carlson & Bultz 2003). Intensive Care Units (ICUs) of hospitals are designed to provide care for critically ill patients (Kongsuwan et al. 2010). Such patients are transferred to ICUs to receive advanced care using sophisticated medical technologies, with the aim of prolonging their life expectancy (Williams et al. 2003). However, even with the critical care which provides in ICU, dying of some patients is inevitable which in turn affects the nurses more than other health care team and could be attributed to the relationship that has formed during caring encounters among the nurse, patient and his or her relatives (Valiee, Negarandeh & Dehghan Nayeri 2012).

Patients in the ICU are cared for and monitored very carefully by a group of health care experts, including nurses (Dunn, Otten & Stephens 2005). During their ICU stay, patients receive constant specialized and critical care from the nursing staff (Hov, Hedelin & Athlin 2007). ICU nurses are commonly trained to cope with any unusual situation that may arise in the ICU (Prompahakul & Nilmanat 2011). Although the main emphasis of health care provision in the ICU is on recovery, many patients still die, at an estimated rate of one out of five admissions (Frommelt 2003). Nevertheless, nurses perform a variety of activities aiming at recovering and preserving physical and psychological integrity of both patients and their family members (Thacker 2008). As a result, many nurses working in ICUs experience a great deal of pain and pressure by the stress they experience from caring for these patients (Rafii, Nikbakht Nasrabadi & Karim 2015).

The ICU environment is generally stressful or emotionally distressing for not only nurses, but also patients and their family members (Hays 2006). Moreover nurses by providing medical care, develop a sympathetic relationship with the seriously diseased or terminally ill patients (Valiee, Negarandeh & Dehghan Nayeri 2012). While performing such critical duties, nursing staff face many challenges in the ICUs (Espinosa et al. 2010). For instance, unwelcome circumstances and conflicts may happen between nurses, physicians, and patients’ families. However, nursing staff are expected to overcome these barriers and remain attentive when caring for critically ill patients (Kirchhoff 2000). Also, inadequate documentation exerts a negative impact on quality care for terminally ill patients; because some patients may receive insufficient treatment due to late recognition of the deterioration, poor documentation, and unsuitable communication (Nelson-Marten, Braaten & English 2001).

While most patients and their families expect greater care in the ICU, shortage of well-trained nurses prevents the provision of standard medical care

(Beckstrand, Callister & Kirchhoff 2006). According to Hansen et al. (2009), provision of effective and advanced care to terminally ill patients requires high levels of knowledge and skill. Moreover, many studies have emphasized on a positive relationship between nurse’s educational level and self-awareness, along with a better delivery of patient’s care (Emami & Nasrabadi 2007). In general, nurses are required to undergo tailored courses to become qualified as an ICU attendant. However, there are no such available training courses in Kurdistan (Moore et al. 2004). Also, study conducted by Salih et al. (2014), reports that Kurdish nurses with qualification regarding ICU provide better care than those who lack relevant education. While some nurses perceive end-of-life care in ICU as an effective and compassionate experience (Beckstrand & Kirchhoff 2005), others feel perplexity, despair, and frustration as reported by nurses in the neuroscience ICU (Calvin, Kite-Powell & Hickey 2007). However, Valiee et al. (2012) concluded that one could barely find pleasure in a workplace where suffering is a constant norm. Accordingly, both pleasure and suffering should be considered in studying Kurdish nurses who work in ICU to be able to find out their feelings and giving proper recommendations.Hence, the present study attempts to explore the feelings and experiences of Kurdish ICU nurses who care for dying patients in the cultural context of Kurdistan Region, Iraq. The outcome of this study would provide evidence on the impact of feelings on the role played by ICU nurses.

2. Materials & Methods

Study design

Kurdish nurses’ feelings and experiences regarding their care for dying patients in the ICU were explored using an inductive content analysis approach (Lichtman 2012).

Participants

A purposive sample of 10 eligible ICU nurses working in Rezgary Teaching Hospital and Hawler Teaching Hospital were recruited with prior approval of the related hospital managers. The inclusion criteria for participation in this study were as follows: 1) being Kurdish registered nurses working in ICUs in Erbil City, 2) having cared for at least three critically ill adult patients, 3) having at least 2 years of ICU experience, and 4) willing to participate in the study.

The participants were five males and five females and their age ranged from 26 to 35 years, with the mean age of 30 years. While seven participants held a BS in nursing, the other three had a diploma in nursing. Years of experience of working in ICU ranged from 4 to 12 years, with a mean of 6 years. During an initial phone call with potential participants, they were provided with detailed description of the study and its risks and benefits, confidentiality of data, and the informed consent procedures.

Data collection

Data were collected through in-depth semi-structured individual interviews. Before the interviews, the study objectives were explained and the participants’ questions and concerns were answered and considered. Individual face-to-face interviews were performed in local language (Kurdish). The participants were asked to describe their feelings and experiences when working in the ICU and subsequent questions were framed around their responses. Follow-up questions were then posed to encourage the participants to further explain their perceptions. These questions included “What feelings make you suffer when working in the ICU?”, “How do you tackle these feelings?”, “What encourages you to continue working in the ICU?”, “How does caring for different patients differ?”, “Can you explain more?”, “Can you give me an example?”, “How did you feel/think about that?”, “What was it like?”, and “You mean ...?” For a better understanding, the interviewer sometimes remained silent as a tactful way to prompt the participants to recall and describe their experiences. The participants were also asked to elaborate on any other aspects which were not covered by interview questions. The interviews were tape recorded and immediately transcribed and analyzed. Each interview lasted 30-60 minutes. The interviews continued until data saturation.

Data analysis

To investigate the feelings and experiences of Kurdish nurses regarding their care for dying patients in the ICU, the qualitative content analysis method was employed (Lichtman 2012). To meet this goal, first the obtained data were translated into English line by line and word by word by a native bilingual person and then inductive content analysis was performed on the transcribed interviews as suggested by Elo and Kyngäs (2008). Accordingly, the first stage of inductive content analysis was open coding during which the transcriptions were read, notes were taken, and the headings were marked in the margin of the text. The headings and categories were created freely to portray all aspects of the provided content. In the second stage, i.e. creating categories, the interviews were reread several times and similar headings were merged to reduce the number of categories and creation of broader categories. The last stage, i.e., abstraction, involved the formulization of a hierarchy for the developed categories. All categories and their subcategories were named based on their lexical content. The highest possible level of abstraction was sought in this process (Elo & Kyngäs 2008).

Trustworthiness

In all qualitative approaches, including content analysis method, trustworthiness is a measure of the level of soundness or adequacy of a research method (Elo & Kyngäs 2008; Holloway & Wheeler 2010). Therefore, when performing a content analysis, the researchers need to accurately describe data analysis procedures and justify the reliability of the results (Elo & Kyngäs 2008). In an attempt to ensure trustworthiness, we determined appropriate times and places for the interviews, tried to win the participants’ trust and establish good relationships with them, benefited from the complementary opinions of our colleagues, and reviewed the handwritten texts. The transcriptions and the extracted codes were checked by two professors. Moreover, the PhD candidate who conducted the interviews had worked in Kurdistan and had relevant experience in critical care nursing.

Ethical considerations

The research project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Before the recruitment of the nurses, prospective participants were called and provided with details on the objectives, risks, and advantages of the study, confidentiality of data, the voluntary nature of participation, and their right to withdraw at any time. In addition upon the recruitment of each nurse, an informed consent was received and before each interview the permission to record was also obtained. During the transcription of interviews, the names of all participants were changed into codes to ensure anonymity. Moreover, the recorded interviews and transcriptions were kept in a safe place.

3. Results

After data analysis, three main categories, including emotional burden, encountering with obstacles, and personal growth emerged. Each category comprised a number of subcategories (Table 1).

Emotional burden

This category reflected the Kurdish nurses’ persistent emotional distress during their caring encounters in the ICU and included two subcategories of “confronting sudden illness and hopeless patients”, and “unreasonable expectations by family members”.

Confronting sudden illness and hopeless patients

Although every ICU nurse is normally confronted with critically ill patients, sometimes an additional sudden illness develops in these patients. Effective management of such circumstances requires extra efforts on behalf of the nursing staff. Participant number 6 perceived these incidents as a challenge in the ICU environment: “There are, sometimes. sudden situations with no prior intimation. You do not expect them to happen, but they do and they add to your worries and anguish”. Furthermore, participant number 4 stated that such unexpected and abrupt situations increase nurses’ occupational stress. The working climate during caring for hopeless patients in ICU was described as distressful and gloomy by this participant. The presence of terminal or hopeless patients in the ICU led the nurses to further despair. Participant number 10 stated: “Since ICU holds terminal or hopeless patients; nurses are always in a sad climate. Having to see such patients all the time affects nurses and makes them feel stressed and depressed”.

Unreasonable expectations by family members

In rare cases, when there is no hope for recovery, family members ask nurses to take the patient off the ventilator or discontinue the treatment to end the patient’s pain and suffering. However nursing staff are not authorized to make such crucial decision and permission from the in charge physician is required. As participant number 3 explained: “It is embarrassing for us when patient` families ask us to discontinue the medicines or to remove the ventilator because euthanasia is not a legal act in Iraqi Kurdistan and not an accepted act in our religion. This unreasonable behavior of family members is distressing for nurses and only nurses are responsible to respond in such a gloomy situation”. This participant continued: “Similar to above example, one day my cousin who was also a close friend of mine passed away because his father decided to take him home from hospital while he was on ventilator. It was a very painful experience”.

Encountering with obstacles

This category reflected how Kurdish nurses were performing difficult tasks in the ICU and included two subcategories of “heavy workload” and “facing anxious families”.

Heavy workload

The heavy workload of ICU nurses emerged as a major concern among the participants. Kurdish ICU nurses performed many additional duties which could lead them to stress and uneasiness: “In our ICU, we have lots of difficulties. We have to do more duties and extra work due to lack of qualified staff and more inflow of critically ill patients”. Heavy workload negatively affects both patient’s safety (because of suboptimal care) and nurses’ job satisfaction. The participants believed that they work beyond their responsibilities and obligations at ICU. Participant number 7 said that “It is quite difficult to keep up with all the duties at ICU due to shortage of nursing staff”. The nurses felt too much work pressure due to lack of nursing staff at ICU as reported by participant number 8: “As the number of nurses per unit doesn’t meet international standards particularly at evening and night shifts, nurses admit to difficulty and fatigability at their work place”.

Facing anxious families

Satisfaction of family members was an important factor in the provision of effective nursing care. In some cases, the decisions or behaviors of family members could adversely affect the performance of nurses. Participant number 1 explained: “Sometimes a patient dies and we inform his/her family about it. They may not believe or bear such bad news. In such cases, besides reassuring the family members, this is only the nurse who has to arrange carrying the dead bodies to their homes”.Dealing with an anxious family was always a major concern for nurses; participant number 7 stated: “When patients’ relatives gather in front of the ICU doors, we as nurses, feel afraid of them! They sometimes command what we must do and this is really demanding and difficult for us”.

Personal growth

During their work, the studied Kurdish nurses felt proud of themselves because of their ability to care for dying patients in the ICU. This category comprised two subcategories, including “self –confidence” and “spiritual satisfaction”.

Self confidence

Since patients were constantly looked after and monitored by ICU nurses; both patients and their families tend to trust them and this in turn had the power to boost nurses’ self-confidence. Participant number 3 mentioned: “Family members believe that the life of their patient is in the hands of nurses. They thus tend to rely on nurses rather than the other members of health care team”. This participant believed that by passing time, they have gained more experience in ICU and are able to make better plans to properly care for patients and it enabled them to work with more passion and confidence. Participant number 5 had this to say: “We have treated so many patients that were beyond everyone’s expectations. Therefore, I feel very content when I see that my colleagues have confidence in me”. And also participant number 4 confirmed that: “I have been working with dying patients in the ICU for a long time. Working in this unit gives me higher levels of confidence and enthusiasm”. Nurses consider themselves as custodians of patient’s health. This spirit was also sensed in the statements of the studied Kurdish nurses, as participant number 6 recalled: “Due to the nature of my job, I have always defended patient’s rights according to international norms and standards. Doing all such extra duties, I feel proud and consider myself more beneficial and better than resident doctors”.

Spiritual satisfaction

The study participants believed that religion plays a very positive role in enhancing their capabilities and have promoted their caring behavior towards patients. As participant number 2 stated: “Only God knows how long a person would live. Therefore, everyone should be patient and contended in life since sometimes miracles can happen. Interestingly, sometimes a patient is declared dead, but breathes again. Prescience belongs solely to God and that’s why we never feel desperate”. Most participants believed that Islam recommends nurses to take care of patients. This encouraged the nurses to continue their caring activities even when there was little chance for survival. Participant number 9 said: “Working in the ICU sometimes leave nurses in a hopeless state, but our religious beliefs help us to handle this negative state of mind and to look forward under any sort of undesirable circumstances”.

4. Discussion

In hospitals, ICUs are held in reserve for patients suffering from severe and life-threatening diseases (Payne, Seymour & Ingleton 2008). Complex and advanced instruments and close monitoring and support are needed to care for these patients. ICU patients also receive specialized care from the medical team, including nurses. Moreover, ICUs are providing terminally ill patients with end-of-life care. The availability of nursing professionals in ICUs is imperative since they perform various duties and play a crucial role in restoring patient’s health (Efstathiou & Clifford 2011). However, due to the presence of critically ill patients, ICU nurses have to cope with constant stress (Gélinas et al. 2012) and Kurdish nurses are not an exception. The present study attempted to shed some light on the experiences of Kurdish nurses working in ICUs to explore their perceptions and feelings.

Stress has been previously reported as one of the most common reactions in ICU nurses (Emami & Nasrabadi 2007). Moreover, levels of stress observed in ICU nurses have been higher than nurses working in other fields (Keane, Ducette & Adler 1985). All of participants in this study reported experiencing some levels of despair because of being aware of patients’ poor prognosis. Due to working in a gloomy environment, the participants became desperate and distressed and thus needed some sort of psychological rehabilitation to help them efficiently cope with such terrible situations. Similarly, some studies have suggested that caring for dying patients is more difficult in the ICU for nurses and other members of health care team (Naidoo 2014). Insufficient resources and shortage of nursing staff are regarded as major concerns for the Kurdish health care system; therefore the extra duties performed in ICU by Kurdish nurses led them to further distress. Adeb-Saeedi (2002) reported that heavy workload pose negative impacts on the performance of nursing staff and the quality of patient’s care. Although this problem is a global issue, nursing managers should adopt any possible approaches (e.g. increasing the number of personnel and nurse/patient ratio) to reduce the workload of critical care units (Valiee, Peyrovi & Nikbakht Nasrabadi 2014). In fact, improving nurses’ working conditions and recruiting adequate nurses based on patients’ inflow may help decrease the feeling of stress among ICU nurses. According to previous studies, a nurse/patient ratio of 1:1 is necessary in ICUs to ensure better care for both emergency and critically ill patients (Beckstrand, Callister & Kirchhoff 2006).

Emotional burden was felt by the nurses in this study and having to deal with the sudden illness in a terminal ill patient was a cause of stress among these participants. Dealing with such distressful circumstances in the ICU requires more urgent management from nursing staff. Death of younger patients is hard to handle emotionally by the whole health care team and thus produces more pain (McMillen 2008). In Kurdistan, patients are generally accompanied by their family members in ICUs (sometimes in large numbers). Many studies have identified the presence of family members in either emergency departments or ICUs as one of the greatest stressors hindering patient care and increasing level of anxiety in nurses (Adeb-Saeedi 2002). Similarly, in the current study, satisfaction of family members was regarded an important factor in the provision of effective nursing care. According to this study, the decision or the behavior of family members frequently and unfavorably affects the performance of Kurdish nurses.

The participants had to encounter with many obstacles. Shortage of well-trained nurses in Kurdistan’s ICUs may directly influence patient’s care. High patients’ inflow, shortage of nurses, and additional duties were actually recognized as sources of stress in Kurdish ICU nurses, especially those working during the night shifts (since most nurses, particularly female nurses, are not willing to work at night due to socio-cultural reasons). The effects of socio-cultural factors on nurses’ performance have also been documented in previous studies (Nikbakht, Emami & Parsa Yekta 2003). Likewise, shortages of sufficient nursing staff in ICUs have been considered as a source of stress in nurses (Chang et al. 2005). Our participants felt disgraced when they were asked by patient families to discontinue medical care. Although it is legally allowed in certain countries like Thailand (Kongsuwan et al. 2010), euthanasia or peaceful death is not a legal act in Kurdistan. However, in rare cases, patient families’ insistence on the cessation of medical care will prompt the doctor to authorize such decision. On the other hand, according to McMillen (2008), the decision of allowing a peaceful death by withdrawing care/treatment in the ICU has remained another challenge that health care staff, especially nurses confront.

Empowerment has been seen as a process of personal growth and development (Kuokkanen, Leino-Kilpi & Katajisto, 2003). Personal growth of nurses in this study was accomplished by the self- confidence and spiritual satisfaction they acquired by caring for ICU patients. High level of self-confidence among Kurdish nurses was accompanied by pride. In fact, as patients and their families showed greater trust in their care, the ICU nurses felt more committed to provide all patients, particularly the critically ill patients with optimal care. Some researchers believe that professional and skillful nurses can improve their potentials by showing enthusiasm in their work (Messmer, Jones & Taylor, 2004). Moreover, other factors such as the effects of religion, high morality, and ability to work independently resulted in more self-confidence and spiritual satisfaction among Kurdish ICU nurses.

Similarly, Valiee et al. (2012) suggested that nurses’ socio-cultural and religious backgrounds have great impacts on their attitude toward life, death, and decision-making about end-of-life care provision. About the study limitation we can mention some points. The findings of this study are based on the feelings and experiences of Kurdish ICU nurses from two major governmental hospitals in Erbil-Iraq and nurses employed in private sections are not included. Furthermore as a qualitative study, the transferability of the findings will be limited to comparable settings. As suggested by Polit and Beck (2008), to make the conviction about transferability easier, it is recommended that researchers make a concise and accurate description of their procedures during their studies. Thus, we attempted to illustrate the area of research as much as possible while respect the confidentiality issue of participant nurses.

ICU nurses in Kurdistan Region of Iraq seem to work sincerely, independently, confidently, and proudly. Despite the challenges during their career, Kurdish ICU nurses have an essential role in the provision of care for critically ill patients. Thus to improve the quality of the provided care in Kurdistan ICUs, the potential sources of emotional and psychological burden among ICU nurses need to be minimized. In spite of their emotional burden related to confronting with ill and hopeless patients and unreasonable expectations by the family members, and also the pressure imposed by heavy workload and anxious patients, Kurdish ICU nurses’ personal growth was enhanced by the self-confidence and spiritual satisfaction they acquired by caring for ill and end stage patients and their families. With no doubt, nurses’ religious beliefs and their special cultural background could partly modify their negative feelings and perceptions. However, in the long run, dealing with these pressures and negative environmental and organizational inhibitors could lead to burnout (Rafii, Oskouie & Nikravesh 2007).

Acknowledgments

The present study was part of the Muaf Abdulla Karim’s PhD dissertation. The authors are grateful to Tehran University of Medical Sciences, International Campus for their support. We also wish to thank the Director of Health in Erbil and the management and nursing staff of the corresponding hospitals and also would like to thank all the participants of the study. This study was funded by Tehran University of Medical Sciences, International Campus, Tehran, Iran.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This category reflected the Kurdish nurses’ persistent emotional distress during their caring encounters in the ICU and included two subcategories of “confronting sudden illness and hopeless patients”, and “unreasonable expectations by family members”.

Confronting sudden illness and hopeless patients

Although every ICU nurse is normally confronted with critically ill patients, sometimes an additional sudden illness develops in these patients. Effective management of such circumstances requires extra efforts on behalf of the nursing staff. Participant number 6 perceived these incidents as a challenge in the ICU environment: “There are, sometimes. sudden situations with no prior intimation. You do not expect them to happen, but they do and they add to your worries and anguish”. Furthermore, participant number 4 stated that such unexpected and abrupt situations increase nurses’ occupational stress. The working climate during caring for hopeless patients in ICU was described as distressful and gloomy by this participant. The presence of terminal or hopeless patients in the ICU led the nurses to further despair. Participant number 10 stated: “Since ICU holds terminal or hopeless patients; nurses are always in a sad climate. Having to see such patients all the time affects nurses and makes them feel stressed and depressed”.

Unreasonable expectations by family members

In rare cases, when there is no hope for recovery, family members ask nurses to take the patient off the ventilator or discontinue the treatment to end the patient’s pain and suffering. However nursing staff are not authorized to make such crucial decision and permission from the in charge physician is required. As participant number 3 explained: “It is embarrassing for us when patient` families ask us to discontinue the medicines or to remove the ventilator because euthanasia is not a legal act in Iraqi Kurdistan and not an accepted act in our religion. This unreasonable behavior of family members is distressing for nurses and only nurses are responsible to respond in such a gloomy situation”. This participant continued: “Similar to above example, one day my cousin who was also a close friend of mine passed away because his father decided to take him home from hospital while he was on ventilator. It was a very painful experience”.

Encountering with obstacles

This category reflected how Kurdish nurses were performing difficult tasks in the ICU and included two subcategories of “heavy workload” and “facing anxious families”.

Heavy workload

The heavy workload of ICU nurses emerged as a major concern among the participants. Kurdish ICU nurses performed many additional duties which could lead them to stress and uneasiness: “In our ICU, we have lots of difficulties. We have to do more duties and extra work due to lack of qualified staff and more inflow of critically ill patients”. Heavy workload negatively affects both patient’s safety (because of suboptimal care) and nurses’ job satisfaction. The participants believed that they work beyond their responsibilities and obligations at ICU. Participant number 7 said that “It is quite difficult to keep up with all the duties at ICU due to shortage of nursing staff”. The nurses felt too much work pressure due to lack of nursing staff at ICU as reported by participant number 8: “As the number of nurses per unit doesn’t meet international standards particularly at evening and night shifts, nurses admit to difficulty and fatigability at their work place”.

Facing anxious families

Satisfaction of family members was an important factor in the provision of effective nursing care. In some cases, the decisions or behaviors of family members could adversely affect the performance of nurses. Participant number 1 explained: “Sometimes a patient dies and we inform his/her family about it. They may not believe or bear such bad news. In such cases, besides reassuring the family members, this is only the nurse who has to arrange carrying the dead bodies to their homes”.Dealing with an anxious family was always a major concern for nurses; participant number 7 stated: “When patients’ relatives gather in front of the ICU doors, we as nurses, feel afraid of them! They sometimes command what we must do and this is really demanding and difficult for us”.

Personal growth

During their work, the studied Kurdish nurses felt proud of themselves because of their ability to care for dying patients in the ICU. This category comprised two subcategories, including “self –confidence” and “spiritual satisfaction”.

Self confidence

Since patients were constantly looked after and monitored by ICU nurses; both patients and their families tend to trust them and this in turn had the power to boost nurses’ self-confidence. Participant number 3 mentioned: “Family members believe that the life of their patient is in the hands of nurses. They thus tend to rely on nurses rather than the other members of health care team”. This participant believed that by passing time, they have gained more experience in ICU and are able to make better plans to properly care for patients and it enabled them to work with more passion and confidence. Participant number 5 had this to say: “We have treated so many patients that were beyond everyone’s expectations. Therefore, I feel very content when I see that my colleagues have confidence in me”. And also participant number 4 confirmed that: “I have been working with dying patients in the ICU for a long time. Working in this unit gives me higher levels of confidence and enthusiasm”. Nurses consider themselves as custodians of patient’s health. This spirit was also sensed in the statements of the studied Kurdish nurses, as participant number 6 recalled: “Due to the nature of my job, I have always defended patient’s rights according to international norms and standards. Doing all such extra duties, I feel proud and consider myself more beneficial and better than resident doctors”.

Spiritual satisfaction

The study participants believed that religion plays a very positive role in enhancing their capabilities and have promoted their caring behavior towards patients. As participant number 2 stated: “Only God knows how long a person would live. Therefore, everyone should be patient and contended in life since sometimes miracles can happen. Interestingly, sometimes a patient is declared dead, but breathes again. Prescience belongs solely to God and that’s why we never feel desperate”. Most participants believed that Islam recommends nurses to take care of patients. This encouraged the nurses to continue their caring activities even when there was little chance for survival. Participant number 9 said: “Working in the ICU sometimes leave nurses in a hopeless state, but our religious beliefs help us to handle this negative state of mind and to look forward under any sort of undesirable circumstances”.

4. Discussion

In hospitals, ICUs are held in reserve for patients suffering from severe and life-threatening diseases (Payne, Seymour & Ingleton 2008). Complex and advanced instruments and close monitoring and support are needed to care for these patients. ICU patients also receive specialized care from the medical team, including nurses. Moreover, ICUs are providing terminally ill patients with end-of-life care. The availability of nursing professionals in ICUs is imperative since they perform various duties and play a crucial role in restoring patient’s health (Efstathiou & Clifford 2011). However, due to the presence of critically ill patients, ICU nurses have to cope with constant stress (Gélinas et al. 2012) and Kurdish nurses are not an exception. The present study attempted to shed some light on the experiences of Kurdish nurses working in ICUs to explore their perceptions and feelings.

Stress has been previously reported as one of the most common reactions in ICU nurses (Emami & Nasrabadi 2007). Moreover, levels of stress observed in ICU nurses have been higher than nurses working in other fields (Keane, Ducette & Adler 1985). All of participants in this study reported experiencing some levels of despair because of being aware of patients’ poor prognosis. Due to working in a gloomy environment, the participants became desperate and distressed and thus needed some sort of psychological rehabilitation to help them efficiently cope with such terrible situations. Similarly, some studies have suggested that caring for dying patients is more difficult in the ICU for nurses and other members of health care team (Naidoo 2014). Insufficient resources and shortage of nursing staff are regarded as major concerns for the Kurdish health care system; therefore the extra duties performed in ICU by Kurdish nurses led them to further distress. Adeb-Saeedi (2002) reported that heavy workload pose negative impacts on the performance of nursing staff and the quality of patient’s care. Although this problem is a global issue, nursing managers should adopt any possible approaches (e.g. increasing the number of personnel and nurse/patient ratio) to reduce the workload of critical care units (Valiee, Peyrovi & Nikbakht Nasrabadi 2014). In fact, improving nurses’ working conditions and recruiting adequate nurses based on patients’ inflow may help decrease the feeling of stress among ICU nurses. According to previous studies, a nurse/patient ratio of 1:1 is necessary in ICUs to ensure better care for both emergency and critically ill patients (Beckstrand, Callister & Kirchhoff 2006).

Emotional burden was felt by the nurses in this study and having to deal with the sudden illness in a terminal ill patient was a cause of stress among these participants. Dealing with such distressful circumstances in the ICU requires more urgent management from nursing staff. Death of younger patients is hard to handle emotionally by the whole health care team and thus produces more pain (McMillen 2008). In Kurdistan, patients are generally accompanied by their family members in ICUs (sometimes in large numbers). Many studies have identified the presence of family members in either emergency departments or ICUs as one of the greatest stressors hindering patient care and increasing level of anxiety in nurses (Adeb-Saeedi 2002). Similarly, in the current study, satisfaction of family members was regarded an important factor in the provision of effective nursing care. According to this study, the decision or the behavior of family members frequently and unfavorably affects the performance of Kurdish nurses.

The participants had to encounter with many obstacles. Shortage of well-trained nurses in Kurdistan’s ICUs may directly influence patient’s care. High patients’ inflow, shortage of nurses, and additional duties were actually recognized as sources of stress in Kurdish ICU nurses, especially those working during the night shifts (since most nurses, particularly female nurses, are not willing to work at night due to socio-cultural reasons). The effects of socio-cultural factors on nurses’ performance have also been documented in previous studies (Nikbakht, Emami & Parsa Yekta 2003). Likewise, shortages of sufficient nursing staff in ICUs have been considered as a source of stress in nurses (Chang et al. 2005). Our participants felt disgraced when they were asked by patient families to discontinue medical care. Although it is legally allowed in certain countries like Thailand (Kongsuwan et al. 2010), euthanasia or peaceful death is not a legal act in Kurdistan. However, in rare cases, patient families’ insistence on the cessation of medical care will prompt the doctor to authorize such decision. On the other hand, according to McMillen (2008), the decision of allowing a peaceful death by withdrawing care/treatment in the ICU has remained another challenge that health care staff, especially nurses confront.

Empowerment has been seen as a process of personal growth and development (Kuokkanen, Leino-Kilpi & Katajisto, 2003). Personal growth of nurses in this study was accomplished by the self- confidence and spiritual satisfaction they acquired by caring for ICU patients. High level of self-confidence among Kurdish nurses was accompanied by pride. In fact, as patients and their families showed greater trust in their care, the ICU nurses felt more committed to provide all patients, particularly the critically ill patients with optimal care. Some researchers believe that professional and skillful nurses can improve their potentials by showing enthusiasm in their work (Messmer, Jones & Taylor, 2004). Moreover, other factors such as the effects of religion, high morality, and ability to work independently resulted in more self-confidence and spiritual satisfaction among Kurdish ICU nurses.

Similarly, Valiee et al. (2012) suggested that nurses’ socio-cultural and religious backgrounds have great impacts on their attitude toward life, death, and decision-making about end-of-life care provision. About the study limitation we can mention some points. The findings of this study are based on the feelings and experiences of Kurdish ICU nurses from two major governmental hospitals in Erbil-Iraq and nurses employed in private sections are not included. Furthermore as a qualitative study, the transferability of the findings will be limited to comparable settings. As suggested by Polit and Beck (2008), to make the conviction about transferability easier, it is recommended that researchers make a concise and accurate description of their procedures during their studies. Thus, we attempted to illustrate the area of research as much as possible while respect the confidentiality issue of participant nurses.

ICU nurses in Kurdistan Region of Iraq seem to work sincerely, independently, confidently, and proudly. Despite the challenges during their career, Kurdish ICU nurses have an essential role in the provision of care for critically ill patients. Thus to improve the quality of the provided care in Kurdistan ICUs, the potential sources of emotional and psychological burden among ICU nurses need to be minimized. In spite of their emotional burden related to confronting with ill and hopeless patients and unreasonable expectations by the family members, and also the pressure imposed by heavy workload and anxious patients, Kurdish ICU nurses’ personal growth was enhanced by the self-confidence and spiritual satisfaction they acquired by caring for ill and end stage patients and their families. With no doubt, nurses’ religious beliefs and their special cultural background could partly modify their negative feelings and perceptions. However, in the long run, dealing with these pressures and negative environmental and organizational inhibitors could lead to burnout (Rafii, Oskouie & Nikravesh 2007).

Acknowledgments

The present study was part of the Muaf Abdulla Karim’s PhD dissertation. The authors are grateful to Tehran University of Medical Sciences, International Campus for their support. We also wish to thank the Director of Health in Erbil and the management and nursing staff of the corresponding hospitals and also would like to thank all the participants of the study. This study was funded by Tehran University of Medical Sciences, International Campus, Tehran, Iran.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2016/07/12 | Accepted: 2016/11/27 | Published: 2017/08/20

Received: 2016/07/12 | Accepted: 2016/11/27 | Published: 2017/08/20

References

1. Abdulla, S., et al., 2014. Nurses' attitude toward the care of dying cases in the cardiac center in Erbil city. Zanco Journal of Medical Sciences, 18(2), pp. 763–8. doi: 10.15218/zjms.2014.0030 [DOI:10.15218/zjms.2014.0030]

2. Adams, A. & Bond, S., 2000. Hospital nurses' job satisfaction, individual and organizational characteristics. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(3), pp. 536-43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01513.x [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01513.x]

3. Adeb-Saeedi, J., 2002. Stress amongst emergency nurses. Australian Emergency Nursing Journal, 5(2), pp. 19–24. doi: 10.1016/s1328-2743(02)80015-3 [DOI:10.1016/S1328-2743(02)80015-3]

4. Beckstrand, R. L. & Kirchhoff, K. T., 2005. Providing end-of-life care to patients: Critical care nurses' perceived obstacles and supportive behaviors. American Journal of Critical Care, 14(5), pp. 395-403. PMID: 16120891 [PMID]

5. Beckstrand, R. L., Callister, L. C. & Kirchhoff, K. T., 2006. Providing a "good death": Critical care nurses' suggestions for improving end-of-life care. American Journal of Critical Care, 15(1), pp. 38-45. PMID: 16391313 [PMID]

6. Calvin, A. O., Kite-Powell, D. M. & Hickey, J. V., 2007. The neuroscience ICU nurse's perceptions about end-of-life care. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 39(3), pp. 143–50. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200706000-00004 [DOI:10.1097/01376517-200706000-00004]

7. Carlson, L. E. & Bultz, B. D., 2003. Benefits of psychosocial oncology care: Improved quality of life and medical cost offset. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1(1), p. 8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-8 [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-1-8]

8. Chang, E. M., et al., 2005. Role stress in nurses: Review of related factors and strategies for moving forward. Nursing and Health Sciences, 7(1), pp. 57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2005.00221.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2005.00221.x]

9. Dunn, K. S., Otten, C. & Stephens, E., 2005. Nursing experience and the care of dying patients. Oncology Nursing Forum, 32(1), pp. 97–104. doi: 10.1188/05.onf.97-104 [DOI:10.1188/05.ONF.97-104]

10. Efstathiou, N. & Clifford, C., 2011. The critical care nurse's role in end of life care: Issues and challenges. Nursing in Critical Care, 16(3), pp. 116-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2010.00438.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1478-5153.2010.00438.x]

11. Elo, S. & Kyngäs, H., 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), pp. 107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x]

12. Emami, A. & Nasrabadi, A. N., 2007. Two approaches to nursing: a study of Iranian nurses. International Nursing Review, 54(2), pp. 137–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00517.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00517.x]

13. Espinosa, L., et al., 2010. ICU nurses' experiences in providing terminal care. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 33(3), pp. 273–81. doi: 10.1097/cnq.0b013e3181d91424 [DOI:10.1097/CNQ.0b013e3181d91424]

14. Ferrell, B. R., Coyle, N. & Paice, J. 2015. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/med/9780199332342.001.0001 [DOI:10.1093/med/9780199332342.001.0001]

15. Frommelt, K. H. M., 2003. Attitudes toward care of the terminally ill: An educational intervention. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 20(1), pp. 13–22. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000108 [DOI:10.1177/104990910302000108]

16. Gélinas, C., et al., 2012. Stressors experienced by nurses providing end-of-life palliative care in the intensive care unit. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 44(1), pp. 18-39. PMID: 22679843 [PMID]

17. Hansen, L., et al., 2009. Nurses' perceptions of end-of-life care after multiple interventions for improvement. American Journal of Critical Care, 18(3), pp. 263-71. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009727 [DOI:10.4037/ajcc2009727]

18. Hays, M. A. et al., 2006. Reported stressors and ways of coping utilized by intensive care unit nurses. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 25(4), pp. 185–93. doi: 10.1097/00003465-200607000-00016. [DOI:10.1097/00003465-200607000-00016]

19. Holloway, I. & Galvin, K., 2010. Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

20. Hov, R., Hedelin, B. & Athlin, E., 2007. Good nursing care to ICU patients on the edge of life. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 23(6), pp. 331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.03.006 [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2007.03.006]

21. Keane, A., Ducette, J. & Adler, D. C., 1985. Stress in ICU and non-ICU nurses. Nursing Research, 34(4), p. 231-6. doi: 10.1097/00006199-198507000-00012 [DOI:10.1097/00006199-198507000-00012]

22. Kirchhoff, K. T., et al., 2000. Intensive care nurses' experiences with end-of-life care. American Journal of Critical Care, 9(1), pp. 36-42. PMID: 10631389 [PMID]

23. Kongsuwan, W. et al., 2010. Thai Buddhist intensive care unit nurses' perspective of a peaceful death: An empirical study. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 16(5), pp. 241–7. Doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.5.48145 [DOI:10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.5.48145]

24. Kuokkanen, L., Leino-Kilpi, H. & Katajisto, J., 2003. Nurse empowerment, job-related satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 18(3), pp. 184–92. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200307000-00004 [DOI:10.1097/00001786-200307000-00004]

25. Lichtman, M., 2012. Qualitative research in education: A user's guide. California: SAGE Publications.

26. McMillen, R. E., 2008. End of life decisions: Nurses perceptions, feelings and experiences. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 24(4), pp. 251–9. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.11.002 [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2007.11.002]

27. Messmer, P. R., Jones, S. G. & Taylor, B. A., 2004. Enhancing knowledge and self-confidence of novice nurses: The "Shadow-A-Nurse" ICU program. Nursing Education Perspectives, 25(3), pp. 131-6. PMID: 15301461 [PMID]

28. Moore, Z. & Price, P., 2004. Nurses' attitudes, behaviours and perceived barriers towards pressure ulcer prevention. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 13(8), pp. 942-51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00972.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00972.x]

29. Naidoo, V., 2014. Experiences of critical care nurses of death and dying in an intensive care unit: A phenomenological study. Journal of Nursing & Care, 3(4). doi: 10.4172/2167-1168.1000179 [DOI:10.4172/2167-1168.1000179]

30. Nelson-Marten, P., Braaten, J. & English, N. K., 2001. Promoting good end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 13(4), pp. 577-85. PMID: 11778345 [PMID]

31. Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A. & Emami, A., 2006. Perceptions of nursing practice in Iran. Nursing Outlook, 54(6), pp. 320–27. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2006.06.001 [DOI:10.1016/j.outlook.2006.06.001]

32. Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A., Emami, A. & Parsa Yekta, Z., 2003. Nursing experience in Iran. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 9(2), pp. 78–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1322-7114.2003.00404.x [DOI:10.1046/j.1322-7114.2003.00404.x]

33. Oberle, K. & Hughes, D., 2001. Doctors' and nurses' perceptions of ethical problems in end of life decisions. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33(6), pp. 707-15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01710.x [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01710.x]

34. Payne, S., Seymour, J. & Ingleton, C., 2008. Palliative care nursing: Principles and evidence for practice: Principles and evidence for practice. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

35. Polit, D. F. & Beck, C. T., 2008. Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

36. Prompahakul, C. & Nilmanat, K., 2011. Factors relating to nurses' caring behaviors for dying patients. Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 1(1), pp. 15-27. doi: 10.14710/nmjn.v1i1.744

37. Rafii, F., Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A. & Karim, M. A., 2015. End-of-life care provision: Experiences of intensive care nurses in Iraq. Nursing in Critical Care, 21(2), pp. 105–12. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12219 [DOI:10.1111/nicc.12219]

38. Rafii, F., Oskouie, F. & Nikravesh, M., 2007. Caring behaviors of burn nurses and the related factors. Burns, 33(3), pp. 299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.397 [DOI:10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.397]

39. Salih, A. A, et al., 2014. Nurses' attitude toward the care of dying cases in the cardiac center in Erbil city. Zanco Journal of Medical Sciences. 18, pp. 763–768 doi: 10.15218/zjms.2014.0030 [DOI:10.15218/zjms.2014.0030]

40. Thacker, K. S., 2008. Nurses' advocacy behaviors in end-of-life nursing care. Nursing Ethics, 15(2), pp. 174-85. doi: 10.1177/0969733007086015 [DOI:10.1177/0969733007086015]

41. Valiee, S., Negarandeh, R. & Dehghan Nayeri, N., 2012. Exploration of Iranian intensive care nurses' experience of end of life care: A qualitative study. Nursing in Critical Care, 17(6), pp. 309-15. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2012.00523.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1478-5153.2012.00523.x]

42. Valiee, S., Peyrovi, H. & Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A., 2014. Critical care nurses' perception of nursing error and its causes: A qualitative study. Contemporary Nurse, 46(2), pp. 206–13. doi: 10.5172/conu.2014.46.2.206 [DOI:10.5172/conu.2014.46.2.206]

43. Williams, R., et al., 2003. A bereavement after-care service for intensive care relatives and staff: The story so far. Nursing in Critical Care, 8(3), pp. 109–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1478-5153.2003.00017.x [DOI:10.1046/j.1478-5153.2003.00017.x]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |