Tue, Aug 26, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 3, Issue 3 (Summer 2017 -- 2017)

JCCNC 2017, 3(3): 215-222 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Cheraghi M A, Bahramnezhad F, Zolfaghari M, Asgari P, Keshmiri F. Design and Psychometric Assessment of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire in Iranian Patients With Spinal Cord Injuries. JCCNC 2017; 3 (3) :215-222

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-146-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-146-en.html

Mohammad Ali Cheraghi1

, Fatemeh Bahramnezhad *2

, Fatemeh Bahramnezhad *2

, Mitra Zolfaghari3

, Mitra Zolfaghari3

, Parvaneh Asgari1

, Parvaneh Asgari1

, Fatemeh Keshmiri4

, Fatemeh Keshmiri4

, Fatemeh Bahramnezhad *2

, Fatemeh Bahramnezhad *2

, Mitra Zolfaghari3

, Mitra Zolfaghari3

, Parvaneh Asgari1

, Parvaneh Asgari1

, Fatemeh Keshmiri4

, Fatemeh Keshmiri4

1- Department of Critical Care Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Critical Care Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,bahramnezhad@sina.tums.ac.ir

3- Department of E-learning in Medical Education, Virtual School, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Educational Development Center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

2- Department of Critical Care Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of E-learning in Medical Education, Virtual School, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Educational Development Center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 570 kb]

(1256 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4204 Views)

Full-Text: (969 Views)

1. Background

Spinal Cord Injuries (SCIs) usually occur following acute traumatic events such as accidents, falling from the height, and shots, which lead to the loss of sense of movement partially or completely (Arango-Lasprilla et al. 2009). Every year, almost 40 new cases of SCI per million are added to the population. This is only about those who survive and are exposed to treatment. Average age of this disorder is 31.5 where at the time of accident 59 % have less than 30 years of age. Injury level in males is four times higher than in females (Kirshblum et al. 2007). SCI causes physical, physiological, sensational, emotional, economic, and social changes in these people and influences their life. People with SCI suffer from problems such as changes in bowel function, bladder, urine and stool control, change in sexual function, respiratory disorders, pain, spasticity of muscles, dependence, pressure sores, and loss of sense of independence (Crewe & Krause 2009). In addition to attachments and losing most of the social and family opportunities, they deal with pressure sores that lead to long-term hospitalization and sometimes are followed by several operations (Jensen et al. 2007). Muscular atrophies, joint pain, shoulder pain, ischemic bursitis, and other biomedical defects constitute other complications of people with SCI that sometimes pain intensifies loss of independence (Wortmann, Valadka & Moores 2008).

Sometimes, these complications aggravate the disease and the person will suffer from depression, mental disorders, and suicide (McDonald & Sadowsky 2002). Since1980sit is well established that purpose in life has a very important role in survival of patients with chronic and threatening diseases (Steger et al. 2006). Purpose gives meaning to life and prepares the person for it (Steger & Kashdan 2006). According to different theories, a true life has a certain meaning that constitutes the foundation to look for understanding the meaning in life (Längle, Orgler & Kundi 2003). The meaning in life means person’s belief in the purpose of life and attempts to achieve the purpose. Numerous factors such as religious beliefs, physical health, and desirable family and social conditions influence the formation of this concept (Emmons 2003; Peterson, Park & Seligman 2005).

Fighting the disease and trying to survive are characterized by specifying the frame of life concept. If the person has defined religion in the frame of life concept, he or she can obtain more strength to tolerate pain (King et al. 2006). Without the meaning in life and goal setting, the life will be full of pain and suffering. Thus, psychologists try to discover patient’s meaning in life and plan accordingly. Since determination of the meaning in life is unique for everybody, it is not possible to define a general criterion (Steger & Frazier 2005). However, previous studies have shown that general meaning in life is defined with respect to the culture in every society. The obvious point is that after traumat-ic events, diseases, and suffering disorders, human changes his or her concept of life (Jim & Andersen 2007). Lack of determination of the meaning in life or its revision after disease drives the person toward depression, anxiety, anger, relentlessness, suicide, lack of interest for treatment, and impaired immune system (King et al. 2006).

According to previous studies, the meaning in life has four dimensions. The first dimension is balance and peace that is accompanied by positive emotions. The second dimension is the existence of dizziness and diminished sense of meaning in person that is created by disease and lack of motivation and directs the person toward meaninglessness (Kiang & Fuligni 2009). Lack of purpose, whether long-term or short-term, constitutes the third dimension of life concept and the last dimension is the spiritual dimension in which some of the cultures have a major role and influences other three dimensions (Steger et al. 2008).

Determination of these four dimensions and formation of the meaning in life and using it in life lead to the progress of the person who tries to have a better life. If the meaning in life is accompanied by problems, it is possible to support the person who is suffering from the problem and promote his or her life quality by improving positive perception in life (Park et al. 2007). Earlier studies suggest that no instrument has been designed in Iran to assess meaning in life. Moreover, there is no reliable and valid instrument in other countries to assess all dimensions of life. However, the reliability of the findings in each study has a direct relationship with the validity of research instruments, and the reader may not obtain necessary confidence and awareness from the quality of validity and its assessment. In this regard, there has been a revolution in the attitude toward meaning in life and the required answer. Most of the scholars in different fields such as philosophy, psychology, religion, and ethics have studied this question and believe that identification of meaning in life can be helpful in planning for satisfaction and adaptation. Thus, a suitable instrument to assess this concept can be effective. Therefore, the present study focused on design and psychometric assessment of meaning in life questionnaire in patients with SCI.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study is a methodological study. The population of this study consisted of patients with SCI who met inclusion criteria (interest in participation, lack of mental disorders, no history in using sedative drugs, lack of dementia, neurogenic disorders, autoimmune disease, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, digestive disease, allergies, asthma, smoking, tobacco, drugs, and alcohol). Therefore, after obtaining ethics code from the ethics committee of Medical Faculty of the University of Tehran, the researcher referred to hospital, park, mosque, and other places in which these people were present and after receiving informed consent, the questionnaires were distributed among them. After self-reporting, data were collected and analyzed using SPSS 16.

In designing the questionnaire, the design procedure of Walt and Ballz tool was combined with the present research method. First, with purposeful studies in databases such as SIDS, Iranmedex, Scopus, PubMed, and Science Direct and using keywords such as meaning in life, SCI, purpose, meaning in life, and reviewing previous studies the items of the questionnaire were designed. A total of 30 articles were found of which 25 articles had full text and were consistent with the topic of interest and finally, 38 items were designed for the questionnaire. This questionnaire was designed based on 5-point Likert scale (agree, relatively agree, no opinion, disagree, and relatively disagree). After preparing the items determination of reliability and validity was done using three methods, namely face validity, content validity, and construct validity.

In face validity, the questions are validated based on their appearance, and this question is asked as to what is the suitable appearance of questions to assess the purpose of interest. To determine face validity, the Impact Score was used. For this purpose, 10 patients with SCI were asked to assess the importance of each itemon5-point Likert scale and select an option. After the interview, the effect of each item was assessed using the following formula:

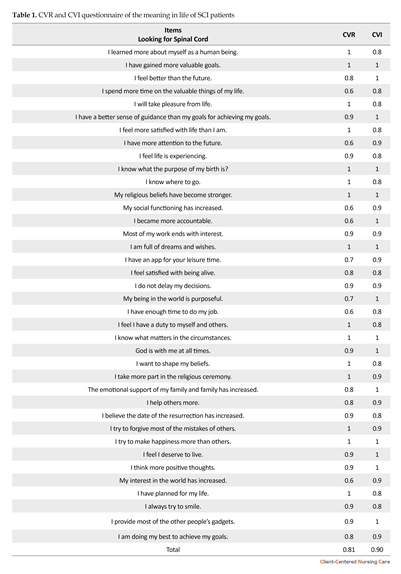

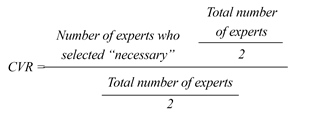

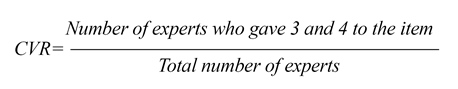

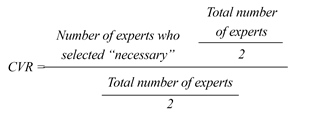

Importance × (frequency %) – impact score

If the score of each item was larger than 1.5, the item was maintained for the next analysis (Hajizadeh & Asghari 2011). Then, questions were assessed by 10 faculty members of Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Tehran as well as Center for Brain and Spinal Cord Remediation at Imam Khomeini Hospital. Indeed, content validity points to this issue that to what extent items are related to the content or meaningfulness dimensions (Alexander & Wilz 2010). In the present study, content validity was investigated in qualitative and quantitative modes. To determine qualitative content validity, experts in the context of interest were asked to investigate items in terms of grammar, use of proper words, and placement of items. Then, quantitative content validity was taken into consideration using Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and Content Validity Index (CVI). CVR, according to Lawshe, determines the necessity of an item by comparing on a 3-point Likert scale (it is necessary, it is beneficial but is not necessary, it is not necessary). Then, to determine the minimum value of the index relative to content validity, items whose ratio was higher than 0.62 % were maintained using Lawshe table and the following formula: This implies that the existence of item related to an acceptable significance level (P < 0.05) is necessary and important (Thompson 2004).

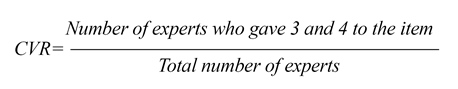

For content validity index, the goal is to determine proportionality, clarity, ambiguity, and relatedness of items regarding the research goal. To determine content validity, questions were distributed among 10 faculty members of Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Tehran as well as Center for Brain and Spinal Cord Remediation at Imam Khomeini Hospital and their comments were assessed on a 4-point Likert scale in terms of clarity and simplicity. Afterwards, content validity of each item and total content validity of the questionnaire were estimated according to the following formula:

Construct validity discusses the relationship between a measurement tool and theoretical background. In other words, construct validity asks the question that how much a measurement instrument reflects theoretical issues. More the reflection, higher the construct validity will be. To determine construct validity, exploratory factor analysis was used. For this purpose, the questionnaire was distributed among 258 patients with SCI. Exploratory factor analysis was performed based on main factors analysis method using Varimax rotation. In different studies, different ratios are stated for required sample size by factor analysis. In this relationship, the minimum ratio of subjects to variables in different studies has been reported from 3 to 1, from 10 to 1, from 15 to 1, and from 20 to 1 (Westen & Rosenthal 2003).

According to the number of items (38 items) in exploratory factor analysis the sample size included 258 subjects, considering the maximum ratio of subjects to variables. To ensure the adequacy of the sample size, Kaiser-Meyer-Oilskin (KMO) was performed where the value of the index was obtained as 0.820 at the significance level of P < 0.0001. Therefore, adequacy and compatibility of data to perform factor analysis were confirmed. In order to determine the internal consistency of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha was used. Further, the test-retest method was used to assess stability over time. For this purpose, the questionnaires were completed by 20 subjects for 2 times with the interval of 1 week. The Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was estimated for three subscales and the questionnaire. ICC value of 0.8 between two tests shows the stability of satisfaction (Pesudovs et al. 2007).

3. Results

Estimation of the effect of items on face validity showed that impact score of all items is larger than 1.5; therefore, all items were found suitable to determine content validity. The results of content validity, by estimating CVR and CVI, were 0.81 and 0.9, respectively (Table 1). Also, all items had the minimum score for construct validity, and all 38 items were used to perform construct validity through exploratory factor analysis. KMO index and Bartlett test confirmed adequacy and capability of data to perform factor analysis (KMO = 0.82). Bartlett test showed the appropriateness of exploratory factor analysis (at the significance level of P = 0.000).

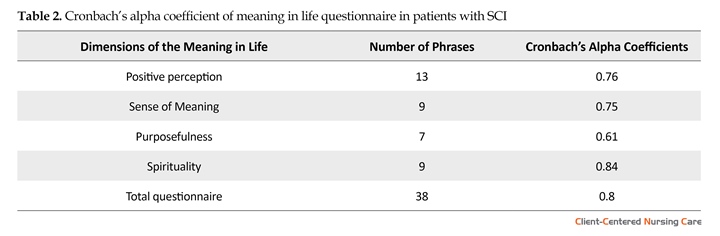

According to the results of factor analysis with Varimax rotation, all questions were assessed with a minimum factor loading of 0.5. Finally, the questionnaire was extracted with 38 items based on 4 factors: the first factor (positive perception) with 13 items and factor loading of 0.549 to 0.723, the second factor (sense of meaning) with 9 items and factor loading of 0.671 to 0.79, the third factor (purposefulness) with 7 items and factor loading of 0.67 to 0.8, and the fourth factor (spirituality) with 9 items and factor loading of 0.58 to 0.70. Internal consistency of the final version of the questionnaire with 38 items was confirmed. Moreover, its Cronbach’s alpha was obtained as 0.8. Internal consistencies of all four domains were estimated and are presented in Table 2.

This questionnaire was designed based on 5-point Likert scale (agree, relatively agree, no opinion, disagree, relatively disagree) with a minimum score of 1 and a maximum score of 5 for each item, and a minimum total score of 38 and a maximum total score of 190. Using norm scale formula on a 5-point Likert scale, three desirable (140-190), average (89-140), and undesirable (38-89) levels were described. ICC of the whole questionnaire was 0.86, which implies high internal consistency of the questionnaire.

4. Discussion

The present study focused on design and psychometric assessment of meaning in life questionnaire of patients with SCI in Iran. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first of its kind questionnaire in Iran. In this study, the questionnaire was designed with 4 factors, namely positive perception, sense of meaning, purposefulness, and spirituality.

The first factor in the present study was positive perception. In this regard, King and colleagues stated that positive perception in life leads to positive behaviors and provides the context for peace and self-confidence. The findings of their study showed that cancer patients who have stronger spiritual dimension and were supported by the family, have a higher positive perception in life (King & Hicks 2009). Additionally, Jim et al. (2006) considered positive perception as the most important factor for women’s adaptation to cancer. In this descriptive and cross-sectional study, women who have a positive perception com-pared with other women could tolerate pain resulted from the disease more easily. The findings of this study showed that women with higher spirituality and purposefulness have better treatment procedure (Jim et al. 2006).

Consistent with the second factor (sense of meaning), Steger states that achieving a meaningful life is one of the most fundamental concerns of humans. Meaningfulness is achieved by satisfying the initial needs and is related to person’s daily activities and functions (Steger, Bundick & Yeager 2011).

About purposefulness in life, Morgan believes that clear and achievable goals give motivation to a person for disease tolerance and the emerged conditions. Purpose and its achievement provide physical, mental, and social happiness to a person and strengthen hope (Morgan & Farsides 2007). Kroosin his descriptive study entitled “the relationship between life and death” on 1361 elderly people showed that those who have stronger religious beliefs have stronger motivation to set goals and try to achieve them. Also, people with stronger meaningfulness have lower mortality and are satisfied with their life. Kroos stated that helping elderlies to find a new meaning can lead to increased lifespan (Krause 2009).

Consistent with the fourth factor (spirituality in life), Steger and Frazier (2005) stated that strengthening the spiritual dimension has an important role in promoting a person’s compatibility with his or her disease and follow-up of the treatment process. They believe that pro

Spinal Cord Injuries (SCIs) usually occur following acute traumatic events such as accidents, falling from the height, and shots, which lead to the loss of sense of movement partially or completely (Arango-Lasprilla et al. 2009). Every year, almost 40 new cases of SCI per million are added to the population. This is only about those who survive and are exposed to treatment. Average age of this disorder is 31.5 where at the time of accident 59 % have less than 30 years of age. Injury level in males is four times higher than in females (Kirshblum et al. 2007). SCI causes physical, physiological, sensational, emotional, economic, and social changes in these people and influences their life. People with SCI suffer from problems such as changes in bowel function, bladder, urine and stool control, change in sexual function, respiratory disorders, pain, spasticity of muscles, dependence, pressure sores, and loss of sense of independence (Crewe & Krause 2009). In addition to attachments and losing most of the social and family opportunities, they deal with pressure sores that lead to long-term hospitalization and sometimes are followed by several operations (Jensen et al. 2007). Muscular atrophies, joint pain, shoulder pain, ischemic bursitis, and other biomedical defects constitute other complications of people with SCI that sometimes pain intensifies loss of independence (Wortmann, Valadka & Moores 2008).

Sometimes, these complications aggravate the disease and the person will suffer from depression, mental disorders, and suicide (McDonald & Sadowsky 2002). Since1980sit is well established that purpose in life has a very important role in survival of patients with chronic and threatening diseases (Steger et al. 2006). Purpose gives meaning to life and prepares the person for it (Steger & Kashdan 2006). According to different theories, a true life has a certain meaning that constitutes the foundation to look for understanding the meaning in life (Längle, Orgler & Kundi 2003). The meaning in life means person’s belief in the purpose of life and attempts to achieve the purpose. Numerous factors such as religious beliefs, physical health, and desirable family and social conditions influence the formation of this concept (Emmons 2003; Peterson, Park & Seligman 2005).

Fighting the disease and trying to survive are characterized by specifying the frame of life concept. If the person has defined religion in the frame of life concept, he or she can obtain more strength to tolerate pain (King et al. 2006). Without the meaning in life and goal setting, the life will be full of pain and suffering. Thus, psychologists try to discover patient’s meaning in life and plan accordingly. Since determination of the meaning in life is unique for everybody, it is not possible to define a general criterion (Steger & Frazier 2005). However, previous studies have shown that general meaning in life is defined with respect to the culture in every society. The obvious point is that after traumat-ic events, diseases, and suffering disorders, human changes his or her concept of life (Jim & Andersen 2007). Lack of determination of the meaning in life or its revision after disease drives the person toward depression, anxiety, anger, relentlessness, suicide, lack of interest for treatment, and impaired immune system (King et al. 2006).

According to previous studies, the meaning in life has four dimensions. The first dimension is balance and peace that is accompanied by positive emotions. The second dimension is the existence of dizziness and diminished sense of meaning in person that is created by disease and lack of motivation and directs the person toward meaninglessness (Kiang & Fuligni 2009). Lack of purpose, whether long-term or short-term, constitutes the third dimension of life concept and the last dimension is the spiritual dimension in which some of the cultures have a major role and influences other three dimensions (Steger et al. 2008).

Determination of these four dimensions and formation of the meaning in life and using it in life lead to the progress of the person who tries to have a better life. If the meaning in life is accompanied by problems, it is possible to support the person who is suffering from the problem and promote his or her life quality by improving positive perception in life (Park et al. 2007). Earlier studies suggest that no instrument has been designed in Iran to assess meaning in life. Moreover, there is no reliable and valid instrument in other countries to assess all dimensions of life. However, the reliability of the findings in each study has a direct relationship with the validity of research instruments, and the reader may not obtain necessary confidence and awareness from the quality of validity and its assessment. In this regard, there has been a revolution in the attitude toward meaning in life and the required answer. Most of the scholars in different fields such as philosophy, psychology, religion, and ethics have studied this question and believe that identification of meaning in life can be helpful in planning for satisfaction and adaptation. Thus, a suitable instrument to assess this concept can be effective. Therefore, the present study focused on design and psychometric assessment of meaning in life questionnaire in patients with SCI.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study is a methodological study. The population of this study consisted of patients with SCI who met inclusion criteria (interest in participation, lack of mental disorders, no history in using sedative drugs, lack of dementia, neurogenic disorders, autoimmune disease, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, digestive disease, allergies, asthma, smoking, tobacco, drugs, and alcohol). Therefore, after obtaining ethics code from the ethics committee of Medical Faculty of the University of Tehran, the researcher referred to hospital, park, mosque, and other places in which these people were present and after receiving informed consent, the questionnaires were distributed among them. After self-reporting, data were collected and analyzed using SPSS 16.

In designing the questionnaire, the design procedure of Walt and Ballz tool was combined with the present research method. First, with purposeful studies in databases such as SIDS, Iranmedex, Scopus, PubMed, and Science Direct and using keywords such as meaning in life, SCI, purpose, meaning in life, and reviewing previous studies the items of the questionnaire were designed. A total of 30 articles were found of which 25 articles had full text and were consistent with the topic of interest and finally, 38 items were designed for the questionnaire. This questionnaire was designed based on 5-point Likert scale (agree, relatively agree, no opinion, disagree, and relatively disagree). After preparing the items determination of reliability and validity was done using three methods, namely face validity, content validity, and construct validity.

In face validity, the questions are validated based on their appearance, and this question is asked as to what is the suitable appearance of questions to assess the purpose of interest. To determine face validity, the Impact Score was used. For this purpose, 10 patients with SCI were asked to assess the importance of each itemon5-point Likert scale and select an option. After the interview, the effect of each item was assessed using the following formula:

Importance × (frequency %) – impact score

If the score of each item was larger than 1.5, the item was maintained for the next analysis (Hajizadeh & Asghari 2011). Then, questions were assessed by 10 faculty members of Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Tehran as well as Center for Brain and Spinal Cord Remediation at Imam Khomeini Hospital. Indeed, content validity points to this issue that to what extent items are related to the content or meaningfulness dimensions (Alexander & Wilz 2010). In the present study, content validity was investigated in qualitative and quantitative modes. To determine qualitative content validity, experts in the context of interest were asked to investigate items in terms of grammar, use of proper words, and placement of items. Then, quantitative content validity was taken into consideration using Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and Content Validity Index (CVI). CVR, according to Lawshe, determines the necessity of an item by comparing on a 3-point Likert scale (it is necessary, it is beneficial but is not necessary, it is not necessary). Then, to determine the minimum value of the index relative to content validity, items whose ratio was higher than 0.62 % were maintained using Lawshe table and the following formula: This implies that the existence of item related to an acceptable significance level (P < 0.05) is necessary and important (Thompson 2004).

For content validity index, the goal is to determine proportionality, clarity, ambiguity, and relatedness of items regarding the research goal. To determine content validity, questions were distributed among 10 faculty members of Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Tehran as well as Center for Brain and Spinal Cord Remediation at Imam Khomeini Hospital and their comments were assessed on a 4-point Likert scale in terms of clarity and simplicity. Afterwards, content validity of each item and total content validity of the questionnaire were estimated according to the following formula:

Construct validity discusses the relationship between a measurement tool and theoretical background. In other words, construct validity asks the question that how much a measurement instrument reflects theoretical issues. More the reflection, higher the construct validity will be. To determine construct validity, exploratory factor analysis was used. For this purpose, the questionnaire was distributed among 258 patients with SCI. Exploratory factor analysis was performed based on main factors analysis method using Varimax rotation. In different studies, different ratios are stated for required sample size by factor analysis. In this relationship, the minimum ratio of subjects to variables in different studies has been reported from 3 to 1, from 10 to 1, from 15 to 1, and from 20 to 1 (Westen & Rosenthal 2003).

According to the number of items (38 items) in exploratory factor analysis the sample size included 258 subjects, considering the maximum ratio of subjects to variables. To ensure the adequacy of the sample size, Kaiser-Meyer-Oilskin (KMO) was performed where the value of the index was obtained as 0.820 at the significance level of P < 0.0001. Therefore, adequacy and compatibility of data to perform factor analysis were confirmed. In order to determine the internal consistency of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha was used. Further, the test-retest method was used to assess stability over time. For this purpose, the questionnaires were completed by 20 subjects for 2 times with the interval of 1 week. The Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was estimated for three subscales and the questionnaire. ICC value of 0.8 between two tests shows the stability of satisfaction (Pesudovs et al. 2007).

3. Results

Estimation of the effect of items on face validity showed that impact score of all items is larger than 1.5; therefore, all items were found suitable to determine content validity. The results of content validity, by estimating CVR and CVI, were 0.81 and 0.9, respectively (Table 1). Also, all items had the minimum score for construct validity, and all 38 items were used to perform construct validity through exploratory factor analysis. KMO index and Bartlett test confirmed adequacy and capability of data to perform factor analysis (KMO = 0.82). Bartlett test showed the appropriateness of exploratory factor analysis (at the significance level of P = 0.000).

According to the results of factor analysis with Varimax rotation, all questions were assessed with a minimum factor loading of 0.5. Finally, the questionnaire was extracted with 38 items based on 4 factors: the first factor (positive perception) with 13 items and factor loading of 0.549 to 0.723, the second factor (sense of meaning) with 9 items and factor loading of 0.671 to 0.79, the third factor (purposefulness) with 7 items and factor loading of 0.67 to 0.8, and the fourth factor (spirituality) with 9 items and factor loading of 0.58 to 0.70. Internal consistency of the final version of the questionnaire with 38 items was confirmed. Moreover, its Cronbach’s alpha was obtained as 0.8. Internal consistencies of all four domains were estimated and are presented in Table 2.

This questionnaire was designed based on 5-point Likert scale (agree, relatively agree, no opinion, disagree, relatively disagree) with a minimum score of 1 and a maximum score of 5 for each item, and a minimum total score of 38 and a maximum total score of 190. Using norm scale formula on a 5-point Likert scale, three desirable (140-190), average (89-140), and undesirable (38-89) levels were described. ICC of the whole questionnaire was 0.86, which implies high internal consistency of the questionnaire.

4. Discussion

The present study focused on design and psychometric assessment of meaning in life questionnaire of patients with SCI in Iran. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first of its kind questionnaire in Iran. In this study, the questionnaire was designed with 4 factors, namely positive perception, sense of meaning, purposefulness, and spirituality.

The first factor in the present study was positive perception. In this regard, King and colleagues stated that positive perception in life leads to positive behaviors and provides the context for peace and self-confidence. The findings of their study showed that cancer patients who have stronger spiritual dimension and were supported by the family, have a higher positive perception in life (King & Hicks 2009). Additionally, Jim et al. (2006) considered positive perception as the most important factor for women’s adaptation to cancer. In this descriptive and cross-sectional study, women who have a positive perception com-pared with other women could tolerate pain resulted from the disease more easily. The findings of this study showed that women with higher spirituality and purposefulness have better treatment procedure (Jim et al. 2006).

Consistent with the second factor (sense of meaning), Steger states that achieving a meaningful life is one of the most fundamental concerns of humans. Meaningfulness is achieved by satisfying the initial needs and is related to person’s daily activities and functions (Steger, Bundick & Yeager 2011).

About purposefulness in life, Morgan believes that clear and achievable goals give motivation to a person for disease tolerance and the emerged conditions. Purpose and its achievement provide physical, mental, and social happiness to a person and strengthen hope (Morgan & Farsides 2007). Kroosin his descriptive study entitled “the relationship between life and death” on 1361 elderly people showed that those who have stronger religious beliefs have stronger motivation to set goals and try to achieve them. Also, people with stronger meaningfulness have lower mortality and are satisfied with their life. Kroos stated that helping elderlies to find a new meaning can lead to increased lifespan (Krause 2009).

Consistent with the fourth factor (spirituality in life), Steger and Frazier (2005) stated that strengthening the spiritual dimension has an important role in promoting a person’s compatibility with his or her disease and follow-up of the treatment process. They believe that pro

moting the spiritual dimension has a close relationship with a person’s religion and beliefs. Indeed, religious beliefs lead to the formation of optimism in people (Steger, Bundick & Yeager 2011). In this regard, Koenig and Almeida stated that religious beliefs lead to developing self-confidence and optimism in people and consequently to different meaning in life, which direct them to build positive aspects and increase life quality. Furthermore, they believe that the aspects of meaning in life such as meaning, positive perception, and high spiritual ability have a rotational state so that strengthening one dimension promotes other dimensions (Moreira-Almeida & Koenig 2006).

Spirituality and mental health are among the factors that predict meaning and purpose in life. The most significant psychological performance of spirituality is related to meaning and purpose in life because they can provide opportunities to look for purpose and meaning in life (Bauer-Wu & Farran 2005).

The present study attempted to design a valid instrument with desirable reliability and validity to assess meaning in life in patients with SCI and prepare necessary arrangements. The findings of the study showed that the designed questionnaire has desirable psychometric characteristics and acceptable validity to assess meaning in life in these patients. However, since the formed items are not directly related to the disease, the researcher hopes to use it in meaning in life assessment in other patients based on the culture of Iranian society. Moreover, the researcher believes that since meaningfulness can be different in different societies and conditions, qualitative studies should be conducted to analyze this concept based on Iranian culture and prepare a more comprehensive questionnaire.

Acknowledgments

This project was approved by the Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (No.17699). The authors are grateful to this center and all those who helped us in doing this project. Also, we are thankful to Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences for financial support from this research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Alexander, T. & Wilz, G., 2010. Family caregivers: Gender differences in adjustment to stroke survivors' mental changes. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(2), p. 159. doi: 10.1037/a0019253

Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. et al., 2009. Influence of race/ethnicity on divorce/separation 1, 2, and 5 years post spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(8), pp. 1371–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.02.006

Bauer Wu, S. & Farran, C. J., 2005. Meaning in life and psycho-spiritual functioning. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 23(2), pp. 172–90. doi: 10.1177/0898010105275927

Crewe, N. M. & Krause, J. S., 2009. Spinal cord injury: Medical, psychosocial and vocational aspects of disability. Athens: Elliott and Fitzpatrick, pp. 289-304.

Emmons, R. A. (2003). Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Wellsprings of a positive life. Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived, pp. 105–28. doi: 10.1037/10594-005

Hajizadeh, E. & Asghari, M. 2011. Statistical methods and analyses in health and biosciences a research methodological approach. Tehran: Jahad-e Daneshgahi Publications.

Jensen, M. P. et al., 2007. Symptom burden in persons with spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(5), pp. 638–45. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.02.002

Jim, H. S. & Andersen, B.L., 2007. Meaning in life mediates the relationship between social and physical functioning and distress in cancer survivors. British Journal of Health Psychology, 12(3), pp. 363–81. doi: 10.1348/135910706x128278

Jim, H. S. et al., 2006. Measuring meaning in life following cancer. Quality of Life Research, 15(8), pp. 1355–71. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0028-6

Kiang, L. & Fuligni, A. J., 2009. Meaning in life as a mediator of ethnic identity and adjustment among adolescents from Latin, Asian, and European American backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(11), pp. 1253–64. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9475-z

King, L. A. & Hicks, J. A., 2009. Detecting and constructing meaning in life events. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(5), pp. 317–30. doi: 10.1080/17439760902992316

King, L. A. et al., 2006. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), pp. 179–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179

Kirshblum, S. C. et al., 2007. Spinal cord injury medicine. 3: Rehabilitation phase after acute spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(3), pp. S62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.003

Krause, N., 2009. Meaning in life and mortality. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64B(4), pp. 517–27. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp047

Längle, A., Orgler, C. & Kundi, M., 2003. The existence scale: A new approach to assess the ability to find personal meaning in life and to reach existential fulfillment. European Psychotherapy, 4(1), pp. 135-51.

McDonald, J. W. & Sadowsky, C., 2002. Spinal-cord injury. The Lancet, 359(9304), pp. 417–25. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(2)07603-1

Moreira-Almeida, A., & Koenig, H. G., 2006. Retaining the meaning of the words religiousness and spirituality: A commentary on the WHOQOL SRPB group's “A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life”(62: 6, 2005, 1486–1497). Social Science & Medicine, 63(4), pp. 843-5. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.001

Morgan, J. & Farsides, T., 2007. Measuring meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(2), pp. 197–214. doi: 10.1007/s10902-007-9075-0

Park, C. L. et al., 2007. Coping, meaning in life, and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Quality of Life Research, 17(1), pp. 21–6. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9279-0

Pesudovs, K. et al., 2007. The development, assessment, and selection of questionnaires. Optometry and Vision Science, 84(8), pp. 663–74. doi: 10.1097/opx.0b013e318141fe75

Peterson, C., Park, N. & Seligman, M.E.P., 2005. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(1), pp. 25–41. doi: 10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z

Steger, M. F. & Frazier, P. , 2005. Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), pp. 574–82. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.574

Steger, M. F. & Kashdan, T. B., 2006. Stability and specificity of meaning in life and life satisfaction over one year. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(2), pp. 161–79. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9011-8

Steger, M. F. et al., 2006. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), pp. 80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

Steger, M. F. et al., 2008. Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76(2), pp. 199–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x

Steger, M. F., Bundick, M. J. & Yeager, D., 2011. Meaning in life. Encyclopedia of Adolescence, pp. 1666–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1695-2_316

Thompson, B., 2004. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications. Worcester, Massachusetts: American Psychological Association.

Westen, D. & Rosenthal, R., 2003. Quantifying construct validity: Two simple measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), pp. 608–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.608

Wortmann, G. W., Valadka, A. B. & Moores, L. E., 2008. Prevention and management of infections associated with combat-related central nervous system injuries. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 64(Supplement), pp. S252–6. doi: 10.1097/ta.0b013e318163d2b7

Spirituality and mental health are among the factors that predict meaning and purpose in life. The most significant psychological performance of spirituality is related to meaning and purpose in life because they can provide opportunities to look for purpose and meaning in life (Bauer-Wu & Farran 2005).

The present study attempted to design a valid instrument with desirable reliability and validity to assess meaning in life in patients with SCI and prepare necessary arrangements. The findings of the study showed that the designed questionnaire has desirable psychometric characteristics and acceptable validity to assess meaning in life in these patients. However, since the formed items are not directly related to the disease, the researcher hopes to use it in meaning in life assessment in other patients based on the culture of Iranian society. Moreover, the researcher believes that since meaningfulness can be different in different societies and conditions, qualitative studies should be conducted to analyze this concept based on Iranian culture and prepare a more comprehensive questionnaire.

Acknowledgments

This project was approved by the Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (No.17699). The authors are grateful to this center and all those who helped us in doing this project. Also, we are thankful to Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences for financial support from this research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Alexander, T. & Wilz, G., 2010. Family caregivers: Gender differences in adjustment to stroke survivors' mental changes. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(2), p. 159. doi: 10.1037/a0019253

Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. et al., 2009. Influence of race/ethnicity on divorce/separation 1, 2, and 5 years post spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(8), pp. 1371–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.02.006

Bauer Wu, S. & Farran, C. J., 2005. Meaning in life and psycho-spiritual functioning. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 23(2), pp. 172–90. doi: 10.1177/0898010105275927

Crewe, N. M. & Krause, J. S., 2009. Spinal cord injury: Medical, psychosocial and vocational aspects of disability. Athens: Elliott and Fitzpatrick, pp. 289-304.

Emmons, R. A. (2003). Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Wellsprings of a positive life. Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived, pp. 105–28. doi: 10.1037/10594-005

Hajizadeh, E. & Asghari, M. 2011. Statistical methods and analyses in health and biosciences a research methodological approach. Tehran: Jahad-e Daneshgahi Publications.

Jensen, M. P. et al., 2007. Symptom burden in persons with spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(5), pp. 638–45. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.02.002

Jim, H. S. & Andersen, B.L., 2007. Meaning in life mediates the relationship between social and physical functioning and distress in cancer survivors. British Journal of Health Psychology, 12(3), pp. 363–81. doi: 10.1348/135910706x128278

Jim, H. S. et al., 2006. Measuring meaning in life following cancer. Quality of Life Research, 15(8), pp. 1355–71. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0028-6

Kiang, L. & Fuligni, A. J., 2009. Meaning in life as a mediator of ethnic identity and adjustment among adolescents from Latin, Asian, and European American backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(11), pp. 1253–64. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9475-z

King, L. A. & Hicks, J. A., 2009. Detecting and constructing meaning in life events. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(5), pp. 317–30. doi: 10.1080/17439760902992316

King, L. A. et al., 2006. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), pp. 179–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179

Kirshblum, S. C. et al., 2007. Spinal cord injury medicine. 3: Rehabilitation phase after acute spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(3), pp. S62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.003

Krause, N., 2009. Meaning in life and mortality. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64B(4), pp. 517–27. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp047

Längle, A., Orgler, C. & Kundi, M., 2003. The existence scale: A new approach to assess the ability to find personal meaning in life and to reach existential fulfillment. European Psychotherapy, 4(1), pp. 135-51.

McDonald, J. W. & Sadowsky, C., 2002. Spinal-cord injury. The Lancet, 359(9304), pp. 417–25. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(2)07603-1

Moreira-Almeida, A., & Koenig, H. G., 2006. Retaining the meaning of the words religiousness and spirituality: A commentary on the WHOQOL SRPB group's “A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life”(62: 6, 2005, 1486–1497). Social Science & Medicine, 63(4), pp. 843-5. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.001

Morgan, J. & Farsides, T., 2007. Measuring meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(2), pp. 197–214. doi: 10.1007/s10902-007-9075-0

Park, C. L. et al., 2007. Coping, meaning in life, and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Quality of Life Research, 17(1), pp. 21–6. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9279-0

Pesudovs, K. et al., 2007. The development, assessment, and selection of questionnaires. Optometry and Vision Science, 84(8), pp. 663–74. doi: 10.1097/opx.0b013e318141fe75

Peterson, C., Park, N. & Seligman, M.E.P., 2005. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(1), pp. 25–41. doi: 10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z

Steger, M. F. & Frazier, P. , 2005. Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), pp. 574–82. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.574

Steger, M. F. & Kashdan, T. B., 2006. Stability and specificity of meaning in life and life satisfaction over one year. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(2), pp. 161–79. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9011-8

Steger, M. F. et al., 2006. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), pp. 80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

Steger, M. F. et al., 2008. Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76(2), pp. 199–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x

Steger, M. F., Bundick, M. J. & Yeager, D., 2011. Meaning in life. Encyclopedia of Adolescence, pp. 1666–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1695-2_316

Thompson, B., 2004. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications. Worcester, Massachusetts: American Psychological Association.

Westen, D. & Rosenthal, R., 2003. Quantifying construct validity: Two simple measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), pp. 608–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.608

Wortmann, G. W., Valadka, A. B. & Moores, L. E., 2008. Prevention and management of infections associated with combat-related central nervous system injuries. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 64(Supplement), pp. S252–6. doi: 10.1097/ta.0b013e318163d2b7

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2016/12/12 | Accepted: 2017/06/20 | Published: 2017/08/1

Received: 2016/12/12 | Accepted: 2017/06/20 | Published: 2017/08/1

References

1. Alexander, T. & Wilz, G., 2010. Family caregivers: Gender differences in adjustment to stroke survivors' mental changes. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(2), p. 159. doi: 10.1037/a0019253 [DOI:10.1037/a0019253]

2. Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. et al., 2009. Influence of race/ethnicity on divorce/separation 1, 2, and 5 years post spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(8), pp. 1371–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.02.006 [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.02.006]

3. Bauer Wu, S. & Farran, C. J., 2005. Meaning in life and psycho-spiritual functioning. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 23(2), pp. 172–90. doi: 10.1177/0898010105275927 [DOI:10.1177/0898010105275927]

4. Crewe, N. M. & Krause, J. S., 2009. Spinal cord injury: Medical, psychosocial and vocational aspects of disability. Athens: Elliott and Fitzpatrick, pp. 289-304.

5. Emmons, R. A. (2003). Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Wellsprings of a positive life. Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived, pp. 105–28. doi: 10.1037/10594-005 [DOI:10.1037/10594-005]

6. Hajizadeh, E. & Asghari, M. 2011. Statistical methods and analyses in health and biosciences a research methodological approach. Tehran: Jahad-e Daneshgahi Publications.

7. Jensen, M. P. et al., 2007. Symptom burden in persons with spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(5), pp. 638–45. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.02.002 [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.02.002]

8. Jim, H. S. & Andersen, B.L., 2007. Meaning in life mediates the relationship between social and physical functioning and distress in cancer survivors. British Journal of Health Psychology, 12(3), pp. 363–81. doi: 10.1348/135910706x128278 [DOI:10.1348/135910706X128278]

9. Jim, H. S. et al., 2006. Measuring meaning in life following cancer. Quality of Life Research, 15(8), pp. 1355–71. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0028-6 [DOI:10.1007/s11136-006-0028-6]

10. Kiang, L. & Fuligni, A. J., 2009. Meaning in life as a mediator of ethnic identity and adjustment among adolescents from Latin, Asian, and European American backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(11), pp. 1253–64. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9475-z [DOI:10.1007/s10964-009-9475-z]

11. King, L. A. & Hicks, J. A., 2009. Detecting and constructing meaning in life events. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(5), pp. 317–30. doi: 10.1080/17439760902992316 [DOI:10.1080/17439760902992316]

12. King, L. A. et al., 2006. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), pp. 179–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179 [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179]

13. Kirshblum, S. C. et al., 2007. Spinal cord injury medicine. 3: Rehabilitation phase after acute spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(3), pp. S62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.003 [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.003]

14. Krause, N., 2009. Meaning in life and mortality. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64B(4), pp. 517–27. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp047 [DOI:10.1093/geronb/gbp047]

15. Längle, A., Orgler, C. & Kundi, M., 2003. The existence scale: A new approach to assess the ability to find personal meaning in life and to reach existential fulfillment. European Psychotherapy, 4(1), pp. 135-51.

16. McDonald, J. W. & Sadowsky, C., 2002. Spinal-cord injury. The Lancet, 359(9304), pp. 417–25. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(2)07603-1

17. Moreira-Almeida, A., & Koenig, H. G., 2006. Retaining the meaning of the words religiousness and spirituality: A commentary on the WHOQOL SRPB group's "A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life"(62: 6, 2005, 1486–1497). Social Science & Medicine, 63(4), pp. 843-5. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.001 [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.001]

18. Morgan, J. & Farsides, T., 2007. Measuring meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(2), pp. 197–214. doi: 10.1007/s10902-007-9075-0 [DOI:10.1007/s10902-007-9075-0]

19. Park, C. L. et al., 2007. Coping, meaning in life, and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Quality of Life Research, 17(1), pp. 21–6. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9279-0 [DOI:10.1007/s11136-007-9279-0]

20. Pesudovs, K. et al., 2007. The development, assessment, and selection of questionnaires. Optometry and Vision Science, 84(8), pp. 663–74. doi: 10.1097/opx.0b013e318141fe75 [DOI:10.1097/OPX.0b013e318141fe75]

21. Peterson, C., Park, N. & Seligman, M.E.P., 2005. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(1), pp. 25–41. doi: 10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z [DOI:10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z]

22. Steger, M. F. & Frazier, P. , 2005. Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), pp. 574–82. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.574 [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.574]

23. Steger, M. F. & Kashdan, T. B., 2006. Stability and specificity of meaning in life and life satisfaction over one year. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(2), pp. 161–79. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9011-8 [DOI:10.1007/s10902-006-9011-8]

24. Steger, M. F. et al., 2006. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), pp. 80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 [DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80]

25. Steger, M. F. et al., 2008. Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76(2), pp. 199–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x]

26. Steger, M. F., Bundick, M. J. & Yeager, D., 2011. Meaning in life. Encyclopedia of Adolescence, pp. 1666–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1695-2_316 [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4419-1695-2_316]

27. Thompson, B., 2004. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications. Worcester, Massachusetts: American Psychological Association. [DOI:10.1037/10694-000]

28. Westen, D. & Rosenthal, R., 2003. Quantifying construct validity: Two simple measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), pp. 608–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.608 [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.608]

29. Wortmann, G. W., Valadka, A. B. & Moores, L. E., 2008. Prevention and management of infections associated with combat-related central nervous system injuries. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 64(Supplement), pp. S252–6. doi: 10.1097/ta.0b013e318163d2b7 [DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e318163d2b7]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |