Wed, May 15, 2024

[Archive]

Volume 4, Issue 1 (Winter 2018 -- 2018)

JCCNC 2018, 4(1): 29-36 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee A, Bagherian M, Rahmatizadeh M. Stress and Coping Strategies in Women With and Without Intimate-Partner Violence Experiences. JCCNC 2018; 4 (1) :29-36

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-156-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-156-en.html

1- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Khatam University, Tehran, Iran. , a.khodabakhshid@khatam.ac.ir

2- Department of Education and Counseling, Faculty of Literature Humanities and Social Sciences, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

3- School of Social Work, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

2- Department of Education and Counseling, Faculty of Literature Humanities and Social Sciences, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

3- School of Social Work, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

Full-Text [PDF 625 kb]

(1273 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2673 Views)

Full-Text: (2532 Views)

1. Background

Intimate-Partner Violence (IPV) is a form of interpersonal violence which can be expressed as physical violence, psychological violence, sexual violence, economic violence, and verbal abuse (Arroyo et al. 2017). This kind of violence occurs in private environment and generally, women and children are subject to disastrous effect of domestic violence (Devries et al. 2013; Savard & Zaouche Gaudron 2014). In recent decades, IPV has been recognized as a serious social problem (Lapierre & Côté 2011; Loseke & Kurz 2005) regardless of cultural, social and regional contexts (Da Fonseca et al. 2011). In other words, it manifests in all societies, as well as in all women, regardless of their intellectual level and socio-professional background (Daoud et al. 2013; Holmes 2012).

To understand the seriousness of this problem, it must be considered that the female population constitutes 49.7% of the total population in Iran (The World Bank 2017), so the consequences of this violence affect the whole society. In addition, the results of quantitative research shows that domestic violence has increased in Iran (Vakili et al. 2010; Nouri et al. 2012). According to a national survey carried out on IPV against women, in 28 provinces of Iran, at least one act of serious physical violence was reported by 66% of married women. Moreover, this survey indicates that 30% of physical domestic violence has led to a temporary or permanent injury in women. Iranian women are more likely to experience the verbal and psychological abuse (Abadi et al. 2012). Likewise, Nouri et al. (2012) reported that the majority of the women (79.7%) have experienced psychological IPV, followed by physical IPV (60%), and sexual IPV (32.9%) in Marivan City, Iran.

Nevertheless, IPV is not usually reported by women because of the stigma, self-blame, fear of losing their children, feelings of shame, denial, improper judgment by others, guilt regarding IPV, or the lack of personal resources to either leave the home or change the situation (Sadeghi 2010; La Flair, Bradshaw & Campbell 2012). Domestic violence can therefore have short- and long-term consequences for the well-being of female victims and their children (Wathen & MacMillan 2013). In this regard, the significant relationship between experiences of partner violence and self-reported poor health was reported by WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence (Ellsberg et al. 2008).

Besides being harmed, women experiencing IPV are at higher risk of developing posttraumatic symptoms (Jackson & Mantler 2017; Weiss et al. 2015; Rashti & Golshokouhi 2010), depression, chronic pain (Rashti & Golshokouhi 2010), gastrointestinal disorders (Moyer 2013), poor pregnancy outcomes (Abdollahi et al. 2015), feeling of helplessness, and other health problems (Baird, Creedy & Mitchell 2017) which may, in turn, lead to serious self-destructive behaviors like substance use (Gibson-McCary & Upchurch 2015), heavy drinking (Aydin et al. 2013), and suicide (Sansone 2016).

Recent studies have indicated that people’s coping strategies in difficult situations vary according to age (Diehl et al. 2014), personality traits (Carver & Connor-smith 2010), intensity and the type of violence (Lazarus 2006). Coping strategies play an important role in managing stressful life events. They are simply certain behaviors and thoughts used to reduce or manage stressful situations and the resulting negative emotions (Bahrami et al. 2016). Coping strategy is a conscious effort to manage stressful and negative demands (internal or external) that surpass an individual’s tolerance.

Coping is a multidimensional concept, composed of different strategies independent of each other: task-oriented (managing or modifying the problem causing distress, active problem-solving approach), emotion-oriented (regulating The emotional response caused by the problem, ruminating, becoming emotional, blaming, worrying), and focused on avoidance (avoiding the situation via distraction by substituting another task, or socially entertaining oneself, others). These strategies can either facilitate the management of stressful situations and the resulting emotions, or have a negative impact on mental and physical health (Bakermans-Kranenburg 2015). A recent study indicated that women experiencing domestic violence may use diverse coping strategies such as seeking social support, problem solving, personal blame, positive reassessment, and avoidance (Sadeghi 2010; Bahrami et al. 2016).

Another factor related to negative impact of IPV is stress vulnerability. Recent studies support the interactions between genes and the environment as the contributing factor to individual susceptibility to stress (Bakermans & Kranenburg 2015). Vulnerability to stress also refers to the limited resources available to respond to the threat and the long-term repercussions for the well-being of the individual (Lallau 2008). It implies a lack of control over an unpredictable and threatening situation.

In other words, vulnerability to stress depends on environmental variables, such as economic and social factors that endanger the individual’s well-being. The symptoms of stress appear only when there exists a relationship between the stressor, the vulnerability of the individual and the context. Obviously certain stimuli are more or less stressful than others, but it is the meaning given to the situation that will influence the individual’s vulnerability and reaction to stress (Lazarus 2006).

However, stress is an inevitable impact of IPV on women; several studies demonstrate that victims of domestic violence are at high risk of developing a variety of mental disorders such as Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Aupperle et al. 2016; Semiatin et al. 2017; Davoren et al. 2017), and anxiety disorder (Rashti & Golshokouhi 2010; Lilly & Graham-Bermann 2010). In fact, there has been a wealth of research that has examined coping styles in IPV situation (Jackson & Mantler 2017; Rizo, Givens & Lombardi 2017; Waldrop & Resick 2004; Saberian et al. 2004) but few studies investigated this issue In Iran (Sadeghi 2010; Bahrami 2016; Folkman & Lazarus 1988).

The acceptance or rejection of IPV is a phenomenon related to cultural, social and personal issues and, thus coping strategy varies according to change in personal and contextual factors (Waldrop & Resick 2004; Saberian et al. 2004); focusing on coping strategy used by women helps in developing of IPV prevention program. This study was carried out with the aim of comparing the coping strategies and vulnerability to stress in women with and without experiences of IPV.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants and plan

This is a descriptive and cross-sectional study conducted in Tehran in 2016. The study sample consisted of two groups, each included 70 women. One group experienced IPV and the other group did not. The group of women with domestic violence experience (IVP group) was recruited by convenience sampling method from the referral of “The center of Imam Ali’s population” and “Welfare Center”. The control group were matched with the IPV group by age and level of education. The inclusion criteria for the IVP group were: 1. Being 20 to 50 years old, 2. Graduating from high school as the minimum level of education, 3. Experiencing IPV within the last year, 4. Lacking any severe mental and physical illnesses, and 5. Having passed more than five years from their marriage.

After registration of the study in Research Committee of Khatam University, the Research Review Board accessed and approved the original study. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants; the researcher informed women that they could interrupt their participation at any time. The questionnaires were completed anonymously.

Study instruments

Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ)

Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ) was designed by Folkman, S. & Lazarus (1988) and used to evaluate the coping strategies employed by individuals to cope with a stressful event. The WCQ includes 66 items, scores on 4-point Likert-type scale, covering a variety of behavioral or cognitive strategies. The instrument measures 8 different strategies: Confrontation (6 Items), distancing (6 Items), exercising self-control (7 Items), social support (6 Items), accepting responsibility or blame (4 Items), escape-avoidance (8 Items), problem-solving (6 Items), and positive reappraisal (7 Items). To calculate the score of the scales, sum ratings for each subscale was used.

Folkman and colleagues (1986) reported the internal coherence coefficients (Cronbach α) as follows: 0.70 for confrontation, 0.76 for distancing, 0.60 for self-control, 0.76 for social support, 0.66 for acceptance of responsibilities, 0.72 for avoidance, 0.67 for problem solving, and 0.79 for positive reassessment (Mahmoud Aliloo et al. 2011). The Persian version of the scale was used in this research. The Cronbach α for the Persian version of the instrument in the present study was 0.86 for total coping strategy, 0.72 for emotional-focused coping strategy, and 0.79 for problem-focused coping strategy.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) has 14 items and measures stress through asking the respondent’ feelings and thoughts during the last month. Participants respond to items on a 4-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). This scale is used to assess the cognitive responses of respondents to a range of stress stimuli; the degree to which individual feels that his or her life events are unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overcrowded (Folkman et al. 1986). The original study reported internal consistency reliabilities (Cronbach α) as 0.86. This score for the Persian version of the scale is 0.81 (Ghorbani et al. 2002). The range of scores varies from 0 to 56, high scores indicates higher levels of stress.

Study procedure

All participants completed 2 questionnaires. Then, the collected data were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA in SPSS V. 22.

3. Results

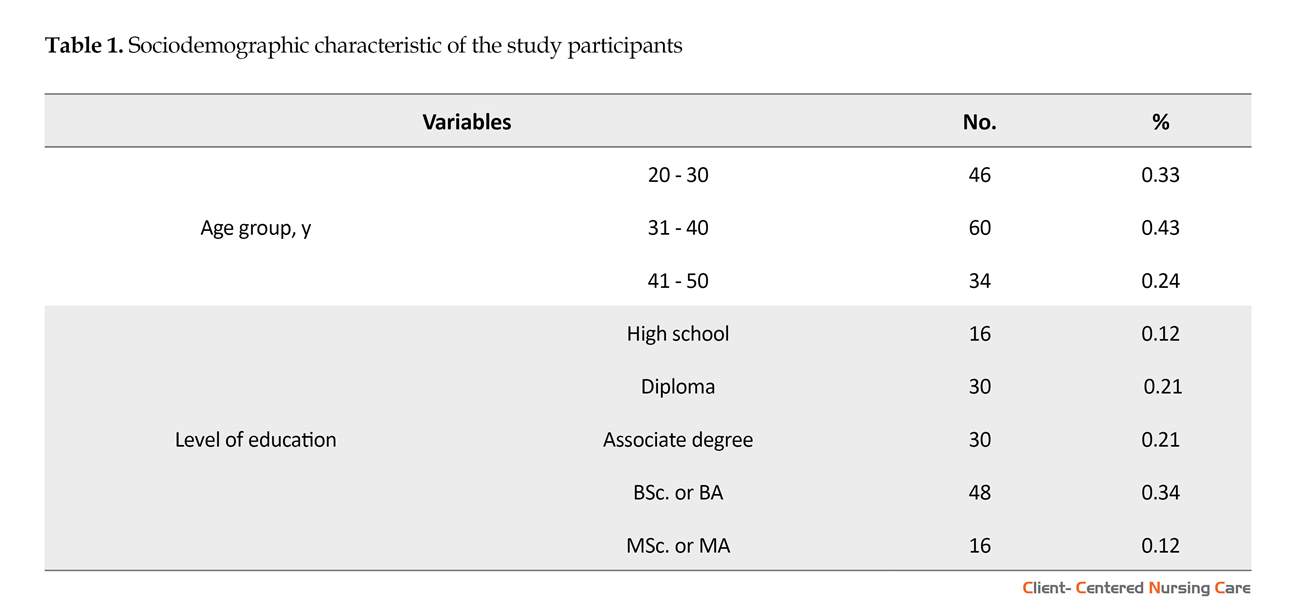

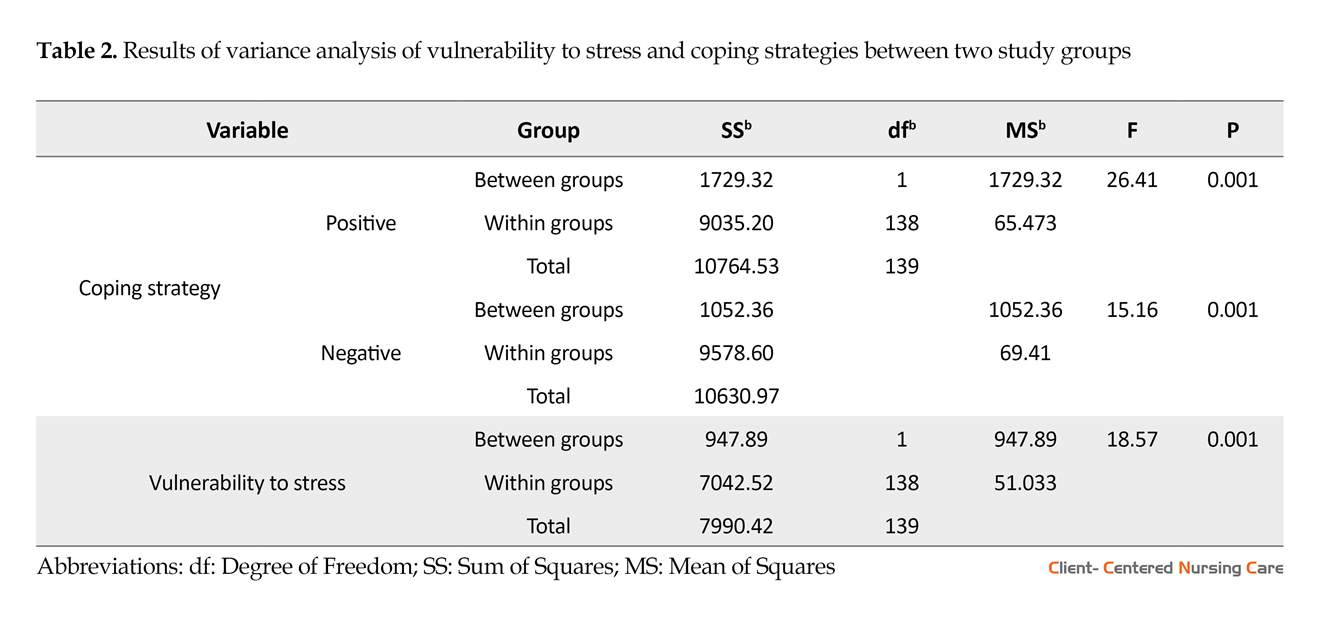

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. As shown in Table 1, most of the women belonged to 31-40 years group and highest percentage of education was baccalaureate degree. Based on Table 2, there is statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of the subscales of problem-focused coping strategies (F=26.41, P=0.001), emotion-focused strategies (F=15.16, P=0.001) and

Intimate-Partner Violence (IPV) is a form of interpersonal violence which can be expressed as physical violence, psychological violence, sexual violence, economic violence, and verbal abuse (Arroyo et al. 2017). This kind of violence occurs in private environment and generally, women and children are subject to disastrous effect of domestic violence (Devries et al. 2013; Savard & Zaouche Gaudron 2014). In recent decades, IPV has been recognized as a serious social problem (Lapierre & Côté 2011; Loseke & Kurz 2005) regardless of cultural, social and regional contexts (Da Fonseca et al. 2011). In other words, it manifests in all societies, as well as in all women, regardless of their intellectual level and socio-professional background (Daoud et al. 2013; Holmes 2012).

To understand the seriousness of this problem, it must be considered that the female population constitutes 49.7% of the total population in Iran (The World Bank 2017), so the consequences of this violence affect the whole society. In addition, the results of quantitative research shows that domestic violence has increased in Iran (Vakili et al. 2010; Nouri et al. 2012). According to a national survey carried out on IPV against women, in 28 provinces of Iran, at least one act of serious physical violence was reported by 66% of married women. Moreover, this survey indicates that 30% of physical domestic violence has led to a temporary or permanent injury in women. Iranian women are more likely to experience the verbal and psychological abuse (Abadi et al. 2012). Likewise, Nouri et al. (2012) reported that the majority of the women (79.7%) have experienced psychological IPV, followed by physical IPV (60%), and sexual IPV (32.9%) in Marivan City, Iran.

Nevertheless, IPV is not usually reported by women because of the stigma, self-blame, fear of losing their children, feelings of shame, denial, improper judgment by others, guilt regarding IPV, or the lack of personal resources to either leave the home or change the situation (Sadeghi 2010; La Flair, Bradshaw & Campbell 2012). Domestic violence can therefore have short- and long-term consequences for the well-being of female victims and their children (Wathen & MacMillan 2013). In this regard, the significant relationship between experiences of partner violence and self-reported poor health was reported by WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence (Ellsberg et al. 2008).

Besides being harmed, women experiencing IPV are at higher risk of developing posttraumatic symptoms (Jackson & Mantler 2017; Weiss et al. 2015; Rashti & Golshokouhi 2010), depression, chronic pain (Rashti & Golshokouhi 2010), gastrointestinal disorders (Moyer 2013), poor pregnancy outcomes (Abdollahi et al. 2015), feeling of helplessness, and other health problems (Baird, Creedy & Mitchell 2017) which may, in turn, lead to serious self-destructive behaviors like substance use (Gibson-McCary & Upchurch 2015), heavy drinking (Aydin et al. 2013), and suicide (Sansone 2016).

Recent studies have indicated that people’s coping strategies in difficult situations vary according to age (Diehl et al. 2014), personality traits (Carver & Connor-smith 2010), intensity and the type of violence (Lazarus 2006). Coping strategies play an important role in managing stressful life events. They are simply certain behaviors and thoughts used to reduce or manage stressful situations and the resulting negative emotions (Bahrami et al. 2016). Coping strategy is a conscious effort to manage stressful and negative demands (internal or external) that surpass an individual’s tolerance.

Coping is a multidimensional concept, composed of different strategies independent of each other: task-oriented (managing or modifying the problem causing distress, active problem-solving approach), emotion-oriented (regulating The emotional response caused by the problem, ruminating, becoming emotional, blaming, worrying), and focused on avoidance (avoiding the situation via distraction by substituting another task, or socially entertaining oneself, others). These strategies can either facilitate the management of stressful situations and the resulting emotions, or have a negative impact on mental and physical health (Bakermans-Kranenburg 2015). A recent study indicated that women experiencing domestic violence may use diverse coping strategies such as seeking social support, problem solving, personal blame, positive reassessment, and avoidance (Sadeghi 2010; Bahrami et al. 2016).

Another factor related to negative impact of IPV is stress vulnerability. Recent studies support the interactions between genes and the environment as the contributing factor to individual susceptibility to stress (Bakermans & Kranenburg 2015). Vulnerability to stress also refers to the limited resources available to respond to the threat and the long-term repercussions for the well-being of the individual (Lallau 2008). It implies a lack of control over an unpredictable and threatening situation.

In other words, vulnerability to stress depends on environmental variables, such as economic and social factors that endanger the individual’s well-being. The symptoms of stress appear only when there exists a relationship between the stressor, the vulnerability of the individual and the context. Obviously certain stimuli are more or less stressful than others, but it is the meaning given to the situation that will influence the individual’s vulnerability and reaction to stress (Lazarus 2006).

However, stress is an inevitable impact of IPV on women; several studies demonstrate that victims of domestic violence are at high risk of developing a variety of mental disorders such as Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Aupperle et al. 2016; Semiatin et al. 2017; Davoren et al. 2017), and anxiety disorder (Rashti & Golshokouhi 2010; Lilly & Graham-Bermann 2010). In fact, there has been a wealth of research that has examined coping styles in IPV situation (Jackson & Mantler 2017; Rizo, Givens & Lombardi 2017; Waldrop & Resick 2004; Saberian et al. 2004) but few studies investigated this issue In Iran (Sadeghi 2010; Bahrami 2016; Folkman & Lazarus 1988).

The acceptance or rejection of IPV is a phenomenon related to cultural, social and personal issues and, thus coping strategy varies according to change in personal and contextual factors (Waldrop & Resick 2004; Saberian et al. 2004); focusing on coping strategy used by women helps in developing of IPV prevention program. This study was carried out with the aim of comparing the coping strategies and vulnerability to stress in women with and without experiences of IPV.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants and plan

This is a descriptive and cross-sectional study conducted in Tehran in 2016. The study sample consisted of two groups, each included 70 women. One group experienced IPV and the other group did not. The group of women with domestic violence experience (IVP group) was recruited by convenience sampling method from the referral of “The center of Imam Ali’s population” and “Welfare Center”. The control group were matched with the IPV group by age and level of education. The inclusion criteria for the IVP group were: 1. Being 20 to 50 years old, 2. Graduating from high school as the minimum level of education, 3. Experiencing IPV within the last year, 4. Lacking any severe mental and physical illnesses, and 5. Having passed more than five years from their marriage.

After registration of the study in Research Committee of Khatam University, the Research Review Board accessed and approved the original study. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants; the researcher informed women that they could interrupt their participation at any time. The questionnaires were completed anonymously.

Study instruments

Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ)

Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ) was designed by Folkman, S. & Lazarus (1988) and used to evaluate the coping strategies employed by individuals to cope with a stressful event. The WCQ includes 66 items, scores on 4-point Likert-type scale, covering a variety of behavioral or cognitive strategies. The instrument measures 8 different strategies: Confrontation (6 Items), distancing (6 Items), exercising self-control (7 Items), social support (6 Items), accepting responsibility or blame (4 Items), escape-avoidance (8 Items), problem-solving (6 Items), and positive reappraisal (7 Items). To calculate the score of the scales, sum ratings for each subscale was used.

Folkman and colleagues (1986) reported the internal coherence coefficients (Cronbach α) as follows: 0.70 for confrontation, 0.76 for distancing, 0.60 for self-control, 0.76 for social support, 0.66 for acceptance of responsibilities, 0.72 for avoidance, 0.67 for problem solving, and 0.79 for positive reassessment (Mahmoud Aliloo et al. 2011). The Persian version of the scale was used in this research. The Cronbach α for the Persian version of the instrument in the present study was 0.86 for total coping strategy, 0.72 for emotional-focused coping strategy, and 0.79 for problem-focused coping strategy.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) has 14 items and measures stress through asking the respondent’ feelings and thoughts during the last month. Participants respond to items on a 4-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). This scale is used to assess the cognitive responses of respondents to a range of stress stimuli; the degree to which individual feels that his or her life events are unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overcrowded (Folkman et al. 1986). The original study reported internal consistency reliabilities (Cronbach α) as 0.86. This score for the Persian version of the scale is 0.81 (Ghorbani et al. 2002). The range of scores varies from 0 to 56, high scores indicates higher levels of stress.

Study procedure

All participants completed 2 questionnaires. Then, the collected data were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA in SPSS V. 22.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. As shown in Table 1, most of the women belonged to 31-40 years group and highest percentage of education was baccalaureate degree. Based on Table 2, there is statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of the subscales of problem-focused coping strategies (F=26.41, P=0.001), emotion-focused strategies (F=15.16, P=0.001) and

vulnerability to stress (F=18.57, P=0.001). In addition, the mean score of emotion-focused coping strategy in women with IPV experience is higher than women without IPV experience. Furthermore, the mean score of vulnerability of stress in women without IPV experience is less than women with IPV experience (Table 2). In other words, this result indicates that the experience of domestic violence increases the vulnerability to stress.

4. Discussion

This study was designed to compare coping strategies and vulnerability to stress in women with IPV experiences and those without these experiences. The findings revealed that women with IPV experiences used more emotion-focused coping style. The coping strategies adopted by women with IPV experiences appeal to cognitive, behavioral or emotional efforts to save them from their stressors. The finding of this study is consistent with behavioral or cognitive mechanisms of Folkman (Folkman et al. 1986). According to this theory, when people seek to decrease their stress by altering its source, they adopt the problem-focused coping style. It includes help seeking, legal action, or staying away from the abuser. However, emotion-focused coping styles include using the emotional support to reduce the stress (Folkman et al. 1986).

Furthermore, using coping strategy may increase or decrease in violence or related stress that included tolerance, harmful behaviors, silence, and retaliation (Sadeghi, 2010; Bahrami et al. 2016). In addition, this finding is comparable with previous study results such as Taherkhani et al. (2016) and Bahrami et al. (2016). In the previous two studies, the researchers reported that the emotion-focused coping style is the common coping

4. Discussion

This study was designed to compare coping strategies and vulnerability to stress in women with IPV experiences and those without these experiences. The findings revealed that women with IPV experiences used more emotion-focused coping style. The coping strategies adopted by women with IPV experiences appeal to cognitive, behavioral or emotional efforts to save them from their stressors. The finding of this study is consistent with behavioral or cognitive mechanisms of Folkman (Folkman et al. 1986). According to this theory, when people seek to decrease their stress by altering its source, they adopt the problem-focused coping style. It includes help seeking, legal action, or staying away from the abuser. However, emotion-focused coping styles include using the emotional support to reduce the stress (Folkman et al. 1986).

Furthermore, using coping strategy may increase or decrease in violence or related stress that included tolerance, harmful behaviors, silence, and retaliation (Sadeghi, 2010; Bahrami et al. 2016). In addition, this finding is comparable with previous study results such as Taherkhani et al. (2016) and Bahrami et al. (2016). In the previous two studies, the researchers reported that the emotion-focused coping style is the common coping

style used by Iranian women, while the effectiveness of adaptation strategies is related to individual and environmental characteristics.

Therefore, this result could be justified by the following reasons; the attitude and culture imposed by Iran’s patriarchal society and traditional values force Iranian women to tolerate and justify IPVs in silence (Abadi et al. 2012). Most women in Iran prefer not to reveal the experience of IPV. They also do not report IPV due to lack of knowledge and recognition of their legal rights or their shame in disclosing the IPV to social workers in judicial centers (Eftekhar et al. 2010).

Many women in Iran do not seek substantial solutions to deal with IPV since they consider it a private matter, therefore they deal with it with individual strategies (Abadi et al. 2012; Eftekhar et al. 2010) which is associated with low level of self-differentiation (Sheikh, Koolaee & Rahmatizadeh 2013). As stated in Iran’s civil law (Article 1105), the husband is the household head and makes a decision for whole family. In this regard, Islam commits woman to obey husband and also recognizes the meeting of husband’s emotional and sexual need as the most important duty of women next to performing her religious duties (Taherkhani et al. 2016).

Obviously such experiences of IPV can duplicate stress and tension in the women that leads to mental disorders (Jackson & Mantler 2017; Weiss et al. 2015; Rashti & Golshokouh 2010) which is inconsistent with the second finding of this study. According to this finding, the vulnerability to stress in women with IPV experiences is more than that in the control group. Folkman (2013) defined stress as a special relationship between the person and the environment in which people evaluate the demands of a situation more than his or her coping resources.

One of the resources available to individuals for dealing with stressor is social support that can be either formal or informal (Khodabakhshi Koolaee, Hosseinian & Falsafinejad 2014). As mentioned above, Iranian women with IPV experiences do not have considerable social and family support due to cultural and traditional issues. Thus, this result is comparable to previous findings in this field (Hosseini, Beyrami & Hashemi 2012; Ziaei et al. 2016; Wiess et al. 2017). Results of Hosseini study among families of supervisor women indicate that emotional-focused coping styles (escape- avoidance, meeting and seeking social support) and social support variables can predict significantly vulnerability against stress (Hosseini, Beyrami & Hashemi 2012).

Several studies reveal that women with IPV experiences are more likely to report physical and emotional symptom of stress (Ziaei et al. 2016; Wiess et al. 2017). The results of Weiss et al. (2017) study among women experiencing partner violence demonstrate that greater avoidance coping is related to more symptoms of PTSD in American women. Rashti and Golshokouh (2010) reported significant correlation between physical-psychological and sexual violence with PTSD among married women. Similarly, some studies indicate that individuals who experience attitudes of rejection (In this case, rejected by family and society) are more vulnerable. Individuals with little defense are vulnerable because they are unable to protect themselves in a violent situation (Gence 2015).

Regarding the findings of the current study that support previous studies, IPV experience impacts on coping strategy chosen by the affected women to manage this stressful situation; it seems that recognition coping strategy with its related factors is the most considerable preventive strategy for decreasing the incident rate of IPV.

Limitations of this study were the lack of sufficient cooperation among women with IPV experiences and also the involved institutions such as the courts and counseling centers, and using a self-report measure which increases the possibility of biased reports. In addition, the use of retrospective data might have further lowered the reliability of the IPV severity.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This paper was extracted from a study approved by Khatam University (ethical code:95/s/403/328).

Funding

This research was funded by Khatam University, Tehran, Iran (Kh-39047).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The researchers express their sincere gratitude to all women who participated in this study.

References

Therefore, this result could be justified by the following reasons; the attitude and culture imposed by Iran’s patriarchal society and traditional values force Iranian women to tolerate and justify IPVs in silence (Abadi et al. 2012). Most women in Iran prefer not to reveal the experience of IPV. They also do not report IPV due to lack of knowledge and recognition of their legal rights or their shame in disclosing the IPV to social workers in judicial centers (Eftekhar et al. 2010).

Many women in Iran do not seek substantial solutions to deal with IPV since they consider it a private matter, therefore they deal with it with individual strategies (Abadi et al. 2012; Eftekhar et al. 2010) which is associated with low level of self-differentiation (Sheikh, Koolaee & Rahmatizadeh 2013). As stated in Iran’s civil law (Article 1105), the husband is the household head and makes a decision for whole family. In this regard, Islam commits woman to obey husband and also recognizes the meeting of husband’s emotional and sexual need as the most important duty of women next to performing her religious duties (Taherkhani et al. 2016).

Obviously such experiences of IPV can duplicate stress and tension in the women that leads to mental disorders (Jackson & Mantler 2017; Weiss et al. 2015; Rashti & Golshokouh 2010) which is inconsistent with the second finding of this study. According to this finding, the vulnerability to stress in women with IPV experiences is more than that in the control group. Folkman (2013) defined stress as a special relationship between the person and the environment in which people evaluate the demands of a situation more than his or her coping resources.

One of the resources available to individuals for dealing with stressor is social support that can be either formal or informal (Khodabakhshi Koolaee, Hosseinian & Falsafinejad 2014). As mentioned above, Iranian women with IPV experiences do not have considerable social and family support due to cultural and traditional issues. Thus, this result is comparable to previous findings in this field (Hosseini, Beyrami & Hashemi 2012; Ziaei et al. 2016; Wiess et al. 2017). Results of Hosseini study among families of supervisor women indicate that emotional-focused coping styles (escape- avoidance, meeting and seeking social support) and social support variables can predict significantly vulnerability against stress (Hosseini, Beyrami & Hashemi 2012).

Several studies reveal that women with IPV experiences are more likely to report physical and emotional symptom of stress (Ziaei et al. 2016; Wiess et al. 2017). The results of Weiss et al. (2017) study among women experiencing partner violence demonstrate that greater avoidance coping is related to more symptoms of PTSD in American women. Rashti and Golshokouh (2010) reported significant correlation between physical-psychological and sexual violence with PTSD among married women. Similarly, some studies indicate that individuals who experience attitudes of rejection (In this case, rejected by family and society) are more vulnerable. Individuals with little defense are vulnerable because they are unable to protect themselves in a violent situation (Gence 2015).

Regarding the findings of the current study that support previous studies, IPV experience impacts on coping strategy chosen by the affected women to manage this stressful situation; it seems that recognition coping strategy with its related factors is the most considerable preventive strategy for decreasing the incident rate of IPV.

Limitations of this study were the lack of sufficient cooperation among women with IPV experiences and also the involved institutions such as the courts and counseling centers, and using a self-report measure which increases the possibility of biased reports. In addition, the use of retrospective data might have further lowered the reliability of the IPV severity.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This paper was extracted from a study approved by Khatam University (ethical code:95/s/403/328).

Funding

This research was funded by Khatam University, Tehran, Iran (Kh-39047).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The researchers express their sincere gratitude to all women who participated in this study.

References

- Abadi, M. N. L., et al., 2012. The buffering effect of social support between domestic violence and self-esteem in pregnant women in Tehran, Iran. Journal of Family Violence, 27(3), pp. 225-31. [DOI:10.1007/s10896-012-9420-x]

- Abdollahi, F., et al., 2015. [Physical violence against pregnant women by an intimate partner, and adverse pregnancy outcomes in Mazandaran Province, Iran (Persian)]. Journal of Family & Community Medicine, 22(1), pp. 13-28. [DOI:10.4103/2230-8229.149577] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Arroyo, K., et al., 2017. Short-term interventions for survivors of intimate partner violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 18(2), pp. 155-71. [DOI:10.1177/1524838015602736] [PMID]

- Aupperle, R. L., et al., 2016. Intimate partner violence PTSD and neural correlates of inhibition. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 29(1), pp. 33-40. [DOI:10.1002/jts.22068] [PMID]

- Aydin, A., et al., 2013. Seasonality of self-destructive behaviour: Seasonal variations in demographic and suicidal characteristics in Van, Turkey. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 17(2), pp. 110-9. [DOI:10.3109/13651501.2012.69756] [PMID]

- Bahrami, M., et al., 2016. Reaction to and coping with domestic violence by Iranian women victims: A qualitative approach. Global Journal of Health Science, 8(7), pp. 100-9. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v8n7p100] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Baird, K., Creedy, D. & Mitchell, T., 2017. Intimate partner violence and pregnancy intentions: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(15-16), pp. 2399-408. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.13394]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. & van IJzendoorn, M. H., 2015. The hidden efficacy of interventions: Gene× environment experiments from a differential susceptibility perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, pp. 381-409. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015407] [PMID]

- Boisvert, A., 2015. [Marriage satisfaction, coping strategies and binge eating (French)] [PhD dissertation]. Quebec: Laval University.

- Carver, C. S. & Connor-Smith, J., 2010. Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, pp. 679-704. [DOI:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352] [PMID]

- Da Fonseca, R. M., et al., 2011. Violence against women: A study of the reports to police in the city of Itapevi, São Paulo, Brazil. Midwifery, 27(4), pp. 469-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.midw.2010.03.004] [PMID]

- Daoud, N., et al., 2013. The contribution of socio-economic position to the excesses of violence and intimate partner violence among Aboriginal versus non-Aboriginal women in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 104(4), pp. e278-83. [DOI:10.17269/cjph.104.3724]

- Davoren, M., et al., 2017. Anxiety disorders and intimate partner violence: Can the association be explained by coexisting conditions or borderline personality traits. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 28(5), pp. 639-58. [DOI:10.1080/14789949.2016.1172659]

- Devries KM, et al., 2013. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science, 340(6140), pp. 1527-8. [DOI:10.1126/science.1240937] [PMID]

- Diehl M., et al., 2014. Change in coping and defense mechanisms across adulthood: Longitudinal findings in a European American sample. Developmental Psychology, 50(2), pp. 634-41. [DOI:10.1037/a0033619] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Eftekhar, H., et al., 2010. Individual features in victims of spouse abuse centers, the organization referred to the coroner. Social Welfare, 12, pp. 259-71.

- Ellsberg, M., et al., 2008. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: An observational study. The Lancet, 371(9619), pp. 1165-72. [DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60522-x]

- Folkman, S. & Lazarus, R. S., 1988. Ways of coping questionnaire. Sunnyvale, California: Consulting Psychologists Press. [PMCID]

- Folkman, S., 2013. Stress: Appraisal and coping. In J. R. Turner, & M. Gellman (eds.), Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. New York: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_215]

- Folkman, S., et al., 1986. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5), p. 992. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992] [PMID]

- Harmattan, L., 2013. [The vulnerability principle (French)]. Louvain: Les Cahiers du CeFap.

- Gence, T., 2015. [The vulnerability to stress induced by managerial situations within Québec companies (French)]. Rimouski: University of Quebec.

- Ghorbani, N., et al., 2002. [Self-reported emotional intelligence: Construct similarity and functional dissimilarity of higher-order processing in Iran and the United States (Persian)]. International Journal of Psychology, 37(5), pp. 297-308. [DOI:10.1080/00207590244000098]

- Gibson-McCrary, D. & Upchurch, D., 2015. Treatment of women and domestic violence in Africa. Journal of Gender, Information and Development in Africa, 4(1-2), pp. 57-69.

- Holmes, M. R., 2012. Long-term effects of intimate partner violence on children’s social behavior [PhD dissertation]. Los Angeles: University of California.

- Hosseini, B. S. M., Beyrami, M. & Hashemi, T., 2012. [The prediction of women vulnerability (family’s women’s supervisor) against stress based on the ratio of social support, coping strategies and locus of control (Persian)]. Psychological Studies, 1(8), pp. 117-40.

- Jackson, K. T. & Mantler, T., 2017. Examining the impact of posttraumatic stress disorder related to intimate partner violence on antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum women: A scoping review. Journal of Family Violence, 32(1), pp. 25-38. [DOI:10.1007/s10896-016-9849-4]

- Khodabakhshi Koolaee, A., Hosseinian, S. & Falsafinejad, M. R., 2014. [Comparing of coping stress strategies and self–concept between married educated women with job and without job (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Career & Organizational Counseling, 6(18), pp. 9-21.

- La Flair, L. N., Bradshaw, C. P. & Campbell, J. C., 2012. Intimate partner violence/abuse and depressive symptoms among female health care workers: Longitudinal findings. Women’s Health Issues, 22(1), pp. e53-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lallau, B., 2008. [African farmers between vulnerability and resilience: For an approach based on the capabilities of risk management (French)]. French Socio-Economic Magazine, 1(1), pp. 177-98. [DOI:10.3917/rfse.001.0177]

- Lapierre, S. & Côté, I., 2011. [We are not there to solve the problem of domestic violence, we are here to protect the child: The conceptualization of domestic violence situations in a youth center in Quebec (French)]. Service Social, 57(1), pp. 31-48. [DOI:10.7202/1006246ar]

- Lazarus, R. S., 2006. Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. Berlin: Springer Publishing Company.

- Lilly, M. M. & Graham-Bermann, S. A., 2010. Intimate partner violence and PTSD: The moderating role of emotion-focused coping. Violence and Victims, 25(5), pp. 604-16. [DOI:10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.604]

- Loseke, D. R. & Kurz, D., 2005. Men’s violence toward women is the serious social problem. Current Controversies on Family Violence, 2, pp. 79-96. [DOI:10.4135/9781483328584.n5]

- Mahmoud Aliloo, M., et al., 2011. Relationship between personality traits and coping styles in HIV positive, addict males. Medical Journal of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, 33(1), pp. 70-6.

- Moyer, V. A., 2013. Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 158(6), pp. 478-86. [DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-158-6-201303190-00588] [PMID]

- Nouri, R., et al., 2012. Prevalence and determinants of intimate partner violence against women in Marivan county, Iran. Journal of Family Violence, 27(5), pp. 391-9. [DOI:10.1007/s10896-012-9440-6]

- Rashti, S. & Golshokouhi, F., 2010. [Relationship between physical-psychological and sexual violence with PTSD in married women (Persain)]. Journal of Social Psychology (New Finding in Psychology), 5(15), pp. 105-14.

- Rizo, C. F., Givens, A. & Lombardi, B., 2017. A systematic review of coping among heterosexual female IPV survivors in the United States with a focus on the conceptualization and measurement of coping. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, pp. 35-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.avb.2017.03.006]

- Saberian, M., et al., 2004. [A survey on the causes and susceptible factors of thedomestic violence and adopting coping methods from women’s views referred to the health care centers in Semnan (2003) (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of Forensic Medicine, 10, pp. 30-4.

- Sadeghi, F. S., 2010. [A qualitative study of domestic violence and women’s coping strategies in Iran (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Social Problem, 1(1), pp. 107-42.

- Sansone, R. A., 2016. Self-harm behaviors among female perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 7(1), pp. 44-56. [DOI:10.1891/1946-6560.7.1.44]

- Savard, N. & Zaouche Gaudron, C., 2014. Violence conjugale, stress maternel et développement de l’enfant. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 46(2), pp. 216-25. [DOI:10.1037/a0030622]

- Semiatin, J. N., et al., 2017. Trauma exposure, PTSD symptoms, and presenting clinical problems among male perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Psychology of Violence, 7(1), pp. 91-100. [DOI:10.1037/vio0000041]

- Sheikh, F., Koolaee, A. K. & Rahmatizadeh, M., 2013. The Comparison of Self-differentiation and self-concept in divorced and non-divorced women who experience domestic violence. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors & Addiction, 2(2), pp. 66-71. [DOI:10.5812/ijhrba.10029]

- Taherkhani, S., et al., 2015. Effect of contextual factors on women coping strategies against domestic violence: A qualitative study. Koomesh, 16(4), pp. 581-94.

- Taherkhani, S., et al., 2016. Iranian women’s strategies for coping with domestic violence. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 5(4), pp. 1-9. [DOI:10.17795/nmsjournal33124]

- The World Bank., 2017. Population, female (% of total). Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

- Vakili, M., et al., 2010. Prevalence and determinants of intimate partner violence against women in Kazeroon, Islamic Republic of Iran. Violence and Victims, 25(1), pp. 116-23.

- Waldrop, A. E. & Resick, P. A., 2004. Coping among adult female victims of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 19(5), pp. 291-302. [DOI:10.1023/b:jofv.0000042079.91846.68]

- Wathen, C. N. & MacMillan, H. L., 2013. Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: Impacts and interventions. Paediatrics & Child Health, 18(8), pp. 419-22. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Weiss, N. H., et al., 2015. The underlying role of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in the association between intimate partner violence and deliberate self-harm among African American women. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 59, pp. 8-16. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.05.018]

- Weiss, N. H., et al., 2017. Racial/ethnic differences moderate associations of coping strategies and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters among women experiencing partner violence: A multigroup path analysis. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 30(3), pp. 347-63. [DOI:10.1080/10615806.2016.1228900] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ziaei S, et al., 2016. Experiencing lifetime domestic violence: Associations with mental health and stress among pregnant women in rural Bangladesh: The MINIMat Randomized Trial. PLoS One, 11(12), p. e0168103. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0168103] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2017/08/10 | Accepted: 2018/03/5 | Published: 2018/02/1

Received: 2017/08/10 | Accepted: 2018/03/5 | Published: 2018/02/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |