Mon, Jun 30, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 4, Issue 4 (Autumn 2018)

JCCNC 2018, 4(4): 231-239 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rezaei M, Izadi-Avanji F S, Safa A, Fernanda Cal S. The Impact of Resilience on the Perception of Chronic Diseases From Older Adults' Perspective. JCCNC 2018; 4 (4) :231-239

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-191-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-191-en.html

1- Autoimmune Disease Research Center, Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

2- Trauma Nursing Research Center, Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran. ,fs.izadi@gmail.com

3- Trauma Nursing Research Center, Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

4- Department of Medicine, Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública (EBMSP), Salvador, Brazil.

2- Trauma Nursing Research Center, Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran. ,

3- Trauma Nursing Research Center, Faculty of Nursing & Midwifery, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran.

4- Department of Medicine, Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública (EBMSP), Salvador, Brazil.

Full-Text [PDF 551 kb]

(1206 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3221 Views)

2. Materials and Methods

Design

Since the main question of the study was “what is older adults' experiences about resilience in the face of chronic disease?” The appropriate research method for answering this question was qualitative content analysis. The study was relied on narrative interviews subjected to a conventional approach to qualitative content analysis.

Content analysis is a research method for interpreting contextual data through systematic classification, coding, and identifying themes and patterns (Seidman 2013). In the current study, raw data were interpreted, summarized, and categorized into classes and themes, based on assumption and explanation (Elo & Kyngs 2008). It is used to discover individuals’ perception of daily life phenomena and interpret content of subjective data (Graneheim & Lundman 2004)

Participants

The participants consisted of elderly with chronic diseases referred to specialized clinics of Shahid Beheshti Hospital in Kashan, Iran. Inclusion criteria were minimum age of 60 years, having one chronic disease at least (confirmed by a specialist), tendency toward expressing inner sights and experiences, and lack of mental illnesses or cognitive impairments. To achieve maximum variation of sampling, participants were recruited with different demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Twenty-five older adults (14 female and 11 male) participated in the study. The participants’ age ranged 60 to 85 years with a mean age of 69.2±6.1. Other characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Data collection

The authors visited the specialized clinics, explained the study objectives and the research questions for eligible patients and interview appointment was scheduled for the cases who had willingness to participate in the study. The participants were selected through purposeful sampling. Data were generated by semi-structured, deep, and face-to-face interviews.

The majority of the interviews were performed privately in a room in the clinic and some were also carried out at the patient’s home. All interviews were started with the main broad questions including “Describe your experience about chronic disease” or “Express your experience from resilience in the face of chronic disease”. To motivate participants to share more and deeper information, follow-up questions and probing such as “please explain more” and “can you give me an example” were used.

All the interviews were recorded using a Samsung Galaxy S5 phone. Interview sessions usually lasted 30 to 60 minutes, with an average of 42 minutes, depending on participants’ tolerance and interest in explaining their own experiences. The process of data gathering was continued until the authors were convinced that no further information would be extracted and data were saturated.

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis were performed simultaneously. This method facilitated forward and backward processes between creating the concepts and data gathering and guided the collection of subsequent data. Also, it facilitated access to relevant information for answering the research questions (Wildemuth 2016). Each interview was transcribed verbatim and analyzed before the next interview took place. The transcripts were entered into MAXQDA software version 7 for encoding. The Graneheim approach to qualitative content analysis was used as the method of data analysis (Graneheim & Lundman 2004).

Each transcript was reviewed multiple times and codes were generated from the respondent’s words and the researcher’s constructs. In the first stage, units of analysis were determined. The term “unit” refers to the end notes that should be analyzed and encoded. In the current study, the full transcript of each interview was considered as the unit of analysis. Words, sentences, and paragraphs were adopted as meaning units. A meaning unit is a set of words or sentences related to each other in the terms of content.

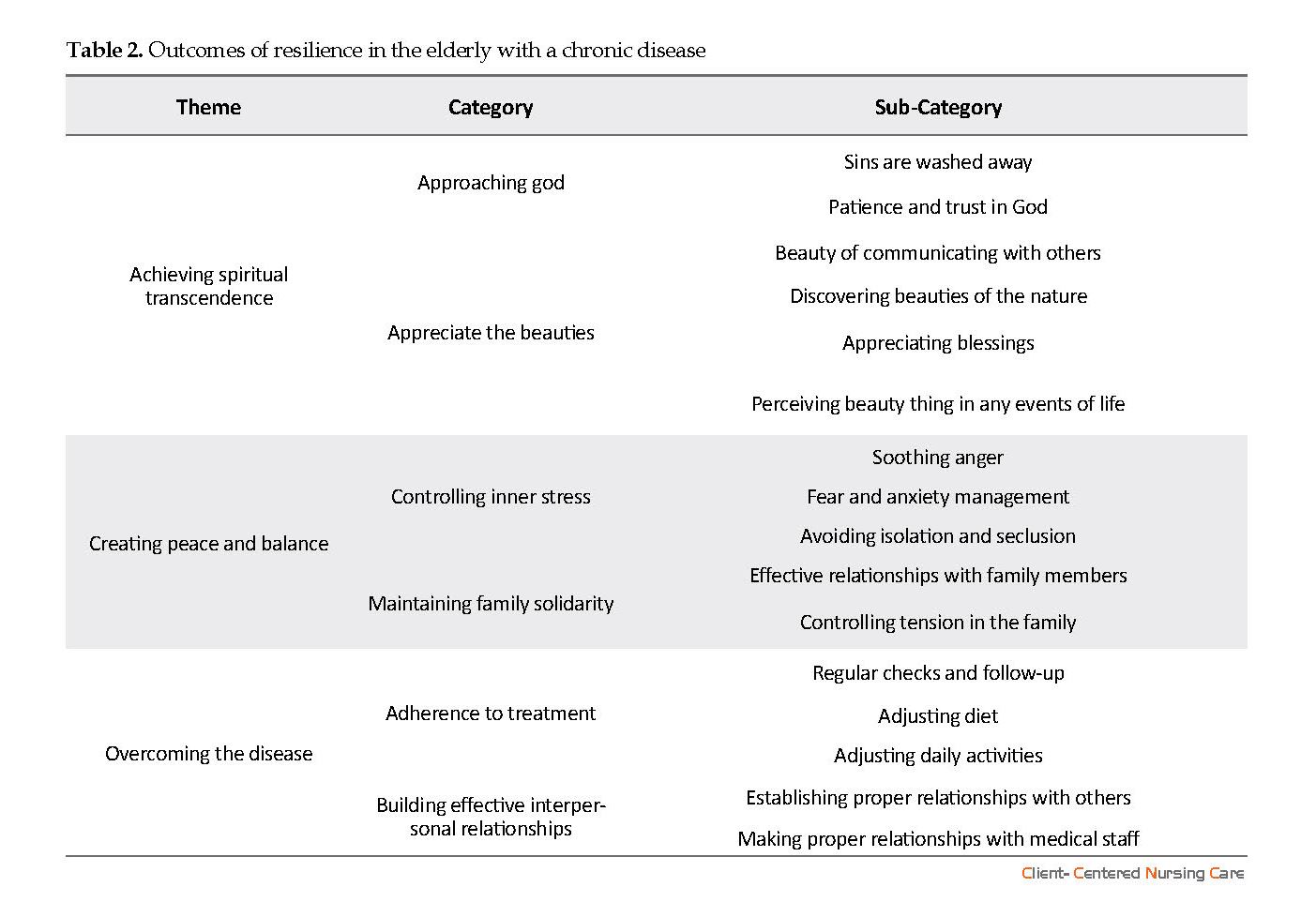

According to their contents, the units were summed up and arranged together and formed condensed meaning units. Then, the condensed meaning units were abstracted and labeled as a code. The various codes were compared based on differences and similarities and sorted into 16 sub-categories and six categories that constitute the manifest content. Finally, the underlying meaning, that is, the latent content of the categories was formulated into three themes.

Rigor and trustworthiness

In the current study, the recommended criteria for the assessment of qualitative data were used (Graneheim 2004; Speziale, Streubert & Carpenter 2011). To ensure credibility of the research, prolonged engagement and peer check were used. In the member checking, after analyzing each interview, the concepts extracted were returned to the participant to approve or modify them. Also, at the end of the study, findings were provided to a number of participants in order to confirm them based on their experiences.

In peer checking, the transcripts of interviews as well as their interpretations were given to four qualitative researchers to modify the interpretations. In order to evaluate the confirm ability of the study, the research process was recorded and the necessary changes along with their reasons and documentations were noted. To improve transferability, the study process was reported in detail and representative quotations were provided from the transcript.

3. Results

Data analysis was conducted based on the study objectives and three main themes were extracted including “achieving spiritual transcendence”, “creating peace and balance”, and “dominating the disease” (Table 2).

Theme 1. Achieving spiritual transcendence

One of the impacts of resilience in the elderly was to achieve spiritual transcendence. By “approaching God” and “appreciate the beauty around”that are possible through resilience in the face of a chronic disease, the participants could achieve transcendence.

Approaching God

The subjects stated that dealing with a chronic disease directed them toward religious and spiritual activities. They believed that God will forgive their sins and they will come closer to God if they endure a chronic disease with the help of religious coping. One participant said:

“Nobody can claim innocence, including me. I have committed sins whether intentional or unintentional. Sustaining the hardships of the disease will wash away my sins” (A 78-year-old male patient with COPD).

“With this illness, I feel closer to God. The reason is that I always tried to utter all my prayers. I continuously chanting, take vow, and try to do anything for others” (A 67-year-old female patient with joint arthritis).

The participants also stated that “patience and trust in God” were the outcomes of resilience and mentioned that through patience and relying on God, they could achieve more positive influences such as God’s satisfaction, heavenly reward, and closeness to God eventually. One participant said:

“There is a good day and a bad day with this disease. I am OK with it now. I can manage it through patience and relying on God; however, I always rely on God. I know that God’s satisfaction relies on my patience and not complaining” (A 70-year-old female patient with renal failure).

Appreciate beauties

The participants mentioned that their ability to pay more attention to beauties, such as “beauty of relationship with others”, “discovering beauty of nature”, “appreciating blessings”, and “perceiving daily beauties of life” were of the outcomes of resilience. A participant said:

“Nothing mattered before the disease, but now everything changed, so that I care more about my grandchildren, children, wife, and relatives. I care more about everything around; I can find a beauty in everything” (A 74-year-old male patient with renal failure).

● The main impacts of resilience in older people are achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease.

● Approaching God and appreciate the beauty around were elements of achieving spiritual transcendence.

● Controlling the inner stress and maintaining the solidarity of family were the constituents of creating peace and balance.

● Compliance with treatment and building effective interpersonal relationships were the constituents of overcoming the disease.

Plain Language Summary

Because of the many problems that occur for the elderly with chronic illnesses, they need higher resilience to overcome their disease. Resilience can lead to positive health outcomes in these people. We investigated the concept of resilience on the perception of chronic disease in a group of older adults. After analyzing the collected data, we found that achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease are outcomes of resilience in these people.

● Approaching God and appreciate the beauty around were elements of achieving spiritual transcendence.

● Controlling the inner stress and maintaining the solidarity of family were the constituents of creating peace and balance.

● Compliance with treatment and building effective interpersonal relationships were the constituents of overcoming the disease.

Plain Language Summary

Because of the many problems that occur for the elderly with chronic illnesses, they need higher resilience to overcome their disease. Resilience can lead to positive health outcomes in these people. We investigated the concept of resilience on the perception of chronic disease in a group of older adults. After analyzing the collected data, we found that achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease are outcomes of resilience in these people.

Full-Text: (1342 Views)

Highlights

● The main impacts of resilience in older people are achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease.

● Approaching God and appreciate the beauty around were elements of achieving spiritual transcendence.

● Controlling the inner stress and maintaining the solidarity of family were the constituents of creating peace and balance.

● Compliance with treatment and building effective interpersonal relationships were the constituents of overcoming the disease.

Plain Language Summary

Because of the many problems that occur for the elderly with chronic illnesses, they need higher resilience to overcome their disease. Resilience can lead to positive health outcomes in these people. We investigated the concept of resilience on the perception of chronic disease in a group of older adults. After analyzing the collected data, we found that achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease are outcomes of resilience in these people.

1. Background

As age increases, the risk of one or more chronic physical illnesses increase, so that the majority of the individuals above 60 deal with at least one chronic condition (Lee 2005). Chronic disease is a long-term complication that causes physical, psychological, and functional problems (Roger et al. 2012; Southwick et al. 2011). Older adults are capable of high resilience despite socioeconomic backgrounds, personal experiences, and declining health (MacLeod et al. 2016). Resilience is one of the predictive factors of positive adaptation to the negative events of life (Bonanno 2004).

It is a factor contributes to successful aging and refers to how to achieve and preserve well-being despite all the challenges related to aging (Ungar 2011). Stein, et al. (2009) defined resilience as the individual ability or endeavor to show positive response to stressful events of life. In a study in Iran, older adults with chronic diseases defined resilience as “the art of overcoming pain and suffer, adaptation to health problems, accepting to live with the chronic disease, and patience and trust in God”(Hassani et al. 2017). Researchers believe that resilience acts as a buffer for negative physical and mental effects of chronic diseases (Franco et al. 2009).

Some elderly with physical and psychological stresses contribute to poor health outcome, while some others can adjust to distresses and return to normal functioning (Mani 2009; Manning 2014). People with poor resilience in the face of stressful events are more susceptible to mental damage (Soroush et al. 2015). Resilience in the elderly develops a sense of connection, independence, and meaningfulness (Alex 2010).

Results of a study on health outcomes in resilient individuals showed that high resilience in the elderly is associated with improved quality of life, mental health, and successful aging perception (Smith & Hollinger-Smith 2015). It is indicated in a review article that high resilience is significantly associated with positive outcomes, including successful aging, lower depression, and longevity (MacLeod et al. 2016). Although numerous studies focused on various specific aspects of resilience, none provided the necessary information about the outcomes of resilience in the older adults with chronic diseases.

Qualitative studies also provided meaning of resilience and its contributors in elderly. This is a clear gap in clinical sciences that needs to be bridged. Explaining elderly experiences with chronic diseases about impacts of resilience can lead to a critical insight into the ways of achieving higher health status. In light of this, the current study aimed at discovering the impacts of resilience on the perception of chronic diseases from older adults’ perspective.

● The main impacts of resilience in older people are achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease.

● Approaching God and appreciate the beauty around were elements of achieving spiritual transcendence.

● Controlling the inner stress and maintaining the solidarity of family were the constituents of creating peace and balance.

● Compliance with treatment and building effective interpersonal relationships were the constituents of overcoming the disease.

Plain Language Summary

Because of the many problems that occur for the elderly with chronic illnesses, they need higher resilience to overcome their disease. Resilience can lead to positive health outcomes in these people. We investigated the concept of resilience on the perception of chronic disease in a group of older adults. After analyzing the collected data, we found that achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease are outcomes of resilience in these people.

1. Background

As age increases, the risk of one or more chronic physical illnesses increase, so that the majority of the individuals above 60 deal with at least one chronic condition (Lee 2005). Chronic disease is a long-term complication that causes physical, psychological, and functional problems (Roger et al. 2012; Southwick et al. 2011). Older adults are capable of high resilience despite socioeconomic backgrounds, personal experiences, and declining health (MacLeod et al. 2016). Resilience is one of the predictive factors of positive adaptation to the negative events of life (Bonanno 2004).

It is a factor contributes to successful aging and refers to how to achieve and preserve well-being despite all the challenges related to aging (Ungar 2011). Stein, et al. (2009) defined resilience as the individual ability or endeavor to show positive response to stressful events of life. In a study in Iran, older adults with chronic diseases defined resilience as “the art of overcoming pain and suffer, adaptation to health problems, accepting to live with the chronic disease, and patience and trust in God”(Hassani et al. 2017). Researchers believe that resilience acts as a buffer for negative physical and mental effects of chronic diseases (Franco et al. 2009).

Some elderly with physical and psychological stresses contribute to poor health outcome, while some others can adjust to distresses and return to normal functioning (Mani 2009; Manning 2014). People with poor resilience in the face of stressful events are more susceptible to mental damage (Soroush et al. 2015). Resilience in the elderly develops a sense of connection, independence, and meaningfulness (Alex 2010).

Results of a study on health outcomes in resilient individuals showed that high resilience in the elderly is associated with improved quality of life, mental health, and successful aging perception (Smith & Hollinger-Smith 2015). It is indicated in a review article that high resilience is significantly associated with positive outcomes, including successful aging, lower depression, and longevity (MacLeod et al. 2016). Although numerous studies focused on various specific aspects of resilience, none provided the necessary information about the outcomes of resilience in the older adults with chronic diseases.

Qualitative studies also provided meaning of resilience and its contributors in elderly. This is a clear gap in clinical sciences that needs to be bridged. Explaining elderly experiences with chronic diseases about impacts of resilience can lead to a critical insight into the ways of achieving higher health status. In light of this, the current study aimed at discovering the impacts of resilience on the perception of chronic diseases from older adults’ perspective.

2. Materials and Methods

Design

Since the main question of the study was “what is older adults' experiences about resilience in the face of chronic disease?” The appropriate research method for answering this question was qualitative content analysis. The study was relied on narrative interviews subjected to a conventional approach to qualitative content analysis.

Content analysis is a research method for interpreting contextual data through systematic classification, coding, and identifying themes and patterns (Seidman 2013). In the current study, raw data were interpreted, summarized, and categorized into classes and themes, based on assumption and explanation (Elo & Kyngs 2008). It is used to discover individuals’ perception of daily life phenomena and interpret content of subjective data (Graneheim & Lundman 2004)

Participants

The participants consisted of elderly with chronic diseases referred to specialized clinics of Shahid Beheshti Hospital in Kashan, Iran. Inclusion criteria were minimum age of 60 years, having one chronic disease at least (confirmed by a specialist), tendency toward expressing inner sights and experiences, and lack of mental illnesses or cognitive impairments. To achieve maximum variation of sampling, participants were recruited with different demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Twenty-five older adults (14 female and 11 male) participated in the study. The participants’ age ranged 60 to 85 years with a mean age of 69.2±6.1. Other characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Data collection

The authors visited the specialized clinics, explained the study objectives and the research questions for eligible patients and interview appointment was scheduled for the cases who had willingness to participate in the study. The participants were selected through purposeful sampling. Data were generated by semi-structured, deep, and face-to-face interviews.

The majority of the interviews were performed privately in a room in the clinic and some were also carried out at the patient’s home. All interviews were started with the main broad questions including “Describe your experience about chronic disease” or “Express your experience from resilience in the face of chronic disease”. To motivate participants to share more and deeper information, follow-up questions and probing such as “please explain more” and “can you give me an example” were used.

All the interviews were recorded using a Samsung Galaxy S5 phone. Interview sessions usually lasted 30 to 60 minutes, with an average of 42 minutes, depending on participants’ tolerance and interest in explaining their own experiences. The process of data gathering was continued until the authors were convinced that no further information would be extracted and data were saturated.

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis were performed simultaneously. This method facilitated forward and backward processes between creating the concepts and data gathering and guided the collection of subsequent data. Also, it facilitated access to relevant information for answering the research questions (Wildemuth 2016). Each interview was transcribed verbatim and analyzed before the next interview took place. The transcripts were entered into MAXQDA software version 7 for encoding. The Graneheim approach to qualitative content analysis was used as the method of data analysis (Graneheim & Lundman 2004).

Each transcript was reviewed multiple times and codes were generated from the respondent’s words and the researcher’s constructs. In the first stage, units of analysis were determined. The term “unit” refers to the end notes that should be analyzed and encoded. In the current study, the full transcript of each interview was considered as the unit of analysis. Words, sentences, and paragraphs were adopted as meaning units. A meaning unit is a set of words or sentences related to each other in the terms of content.

According to their contents, the units were summed up and arranged together and formed condensed meaning units. Then, the condensed meaning units were abstracted and labeled as a code. The various codes were compared based on differences and similarities and sorted into 16 sub-categories and six categories that constitute the manifest content. Finally, the underlying meaning, that is, the latent content of the categories was formulated into three themes.

Rigor and trustworthiness

In the current study, the recommended criteria for the assessment of qualitative data were used (Graneheim 2004; Speziale, Streubert & Carpenter 2011). To ensure credibility of the research, prolonged engagement and peer check were used. In the member checking, after analyzing each interview, the concepts extracted were returned to the participant to approve or modify them. Also, at the end of the study, findings were provided to a number of participants in order to confirm them based on their experiences.

In peer checking, the transcripts of interviews as well as their interpretations were given to four qualitative researchers to modify the interpretations. In order to evaluate the confirm ability of the study, the research process was recorded and the necessary changes along with their reasons and documentations were noted. To improve transferability, the study process was reported in detail and representative quotations were provided from the transcript.

3. Results

Data analysis was conducted based on the study objectives and three main themes were extracted including “achieving spiritual transcendence”, “creating peace and balance”, and “dominating the disease” (Table 2).

Theme 1. Achieving spiritual transcendence

One of the impacts of resilience in the elderly was to achieve spiritual transcendence. By “approaching God” and “appreciate the beauty around”that are possible through resilience in the face of a chronic disease, the participants could achieve transcendence.

Approaching God

The subjects stated that dealing with a chronic disease directed them toward religious and spiritual activities. They believed that God will forgive their sins and they will come closer to God if they endure a chronic disease with the help of religious coping. One participant said:

“Nobody can claim innocence, including me. I have committed sins whether intentional or unintentional. Sustaining the hardships of the disease will wash away my sins” (A 78-year-old male patient with COPD).

“With this illness, I feel closer to God. The reason is that I always tried to utter all my prayers. I continuously chanting, take vow, and try to do anything for others” (A 67-year-old female patient with joint arthritis).

The participants also stated that “patience and trust in God” were the outcomes of resilience and mentioned that through patience and relying on God, they could achieve more positive influences such as God’s satisfaction, heavenly reward, and closeness to God eventually. One participant said:

“There is a good day and a bad day with this disease. I am OK with it now. I can manage it through patience and relying on God; however, I always rely on God. I know that God’s satisfaction relies on my patience and not complaining” (A 70-year-old female patient with renal failure).

Appreciate beauties

The participants mentioned that their ability to pay more attention to beauties, such as “beauty of relationship with others”, “discovering beauty of nature”, “appreciating blessings”, and “perceiving daily beauties of life” were of the outcomes of resilience. A participant said:

“Nothing mattered before the disease, but now everything changed, so that I care more about my grandchildren, children, wife, and relatives. I care more about everything around; I can find a beauty in everything” (A 74-year-old male patient with renal failure).

Other participants also stated

“All that I see is beauty and mightiness of God” (A 67-year-old male patient with Parkinson’s disease).

Being aware and grateful for blessing was another outcome of resilience in patients with chronic diseases:

“Now that I am sick, I appreciate my blessings more than before. I thought that life meant money, but now it is different and everything around me is more important and beautiful to me” (A 80-year-old male patient with diabetes).

Resilience and coping with the hardship of a chronic disease made the participants to find daily events, so that they believed that there would be something good in their daily lives incidents:

“There is a beautiful thing in any event in a person’s life, which might be concealed from views. One of them is my blood disease. It was started with a toothache and when the doctor pulled it out, the bleeding did not stop. Then we found that I have a blood issue” (A 68-year-old male patient with leukemia).

Theme 2. Creating peace and balance

Resilience during the exacerbation of symptoms of the disease led to “creating peace and balance” in life of the elderly and their family members.

Controlling the inner stress

Due to the decrease of functional capacity and the exacerbation of symptoms, stress was one of the main issues that the elderly faced with it. The participants’ experiences showed that coping with difficult situations enabled them to better control negative psychological responses such as anger, fear, anxiety, and isolation.

“I had a severe pain in my legs overnight for the past 20 years. I could control myself through being a resilient. I learned that worrying is absurd and I need to control it” (A 67-year-old female patient with spinal stenosis).

“At first, the pain was limited to the hands and joints and I was very impatient and secluded as well. I did not like to leave home. However, I gradually managed my nerve and find a solution instead of feeling pity for myself” (A 65-year-old female patient with lupus).

Maintaining solidarity of family

Participants stated that their resilience, especially during exacerbation of the symptoms, led to “effective relationship with family members”; so that there was a lower level of stress among family members. This phenomenon is rooted in their attempts to maintain solidarity and cooperative attitudes in the family and provide a better atmosphere to express positive and negative insights. Consequently, family solidarity, peace, and balance are improved and there is less tension among the family members.

“I have been with this disease for 30 years. By being a resilient, not only I could manage my family, but there is now more sense of solidarity in the family” (A 65-year-old female patient with lupus).

Theme 3. Overcoming the disease

The participants’ statements showed that resilience is a key factor in controlling and managing the disease. Resilient patients had compliance with the treatment plan and overcame their disease by making effective communications.

Adherence to treatment

The participants mentioned that resilience enabled them to accept changes in their diet and daily life activities and experience a higher level of wellbeing.

“I have been a diabetic patient for years. The kidneys work well and I have no wound on my feet. For this, I have strict adherence to my treatment plan. I also check my blood sugar level regularly. All these enable me to have a good control over the disease and the symptoms” (An 82-year-old male patient with diabetes).

Building effective interpersonal relationships

The participants stated that their resilience led to establishment of an “effective relationship with others and medical staff”. They also added that clear and proper verbal and non-verbal interactions with others helped them to enjoy emotional, financial, and functional supports from others. Moreover, having a proper interaction with the medical staff facilitated receiving medical services.

“When I need to check my kidneys, I call my children and ask one of them to take me to the doctor. I tell them that I can also take a taxi and there would be no hard feeling if they are not available, but they are always available willfully” (A 65-year-old female patient with lupus).

“I call my family members or emergency medical services when I need a medical care. They either tell me what to do or come to help me” (A 74-year-old female patient with renal failure). The themes, categories, and sub-categories are summarized in Table 2.

4. Discussion

The findings revealed that resilience led to achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease. Achieving spiritual transcendence was one the outcomes of resilience. It seems that there is a reciprocal relationship between resilience and spirituality; so that the former enforces the latter. Resilience is developed through a process of failure and reintegration. Reintegration needs energy, which should be supplied from a spiritual source (Mackay 2003).

Spirituality provides opportunity for reinterpreting the events beyond one’s control so that the event would appear less stressful and more controllable. Moreover, considering negative events as the factors beyond one’s control creates an optimistic style (Kiken & Shook 2011). All these provide grounds for higher resilience in the face of hardships (Aukst-Margetic & Margetic 2005). A significant relationship was observed between resilience and spiritual wellbeing in the elderly (Smith, Webber, & DeFrain 2013).

Another outcome of resilience was perception of the beauties, so that the participants were able to see the beauties of relationship with others and the surrounding nature. Moreover, they could find beauties in daily life and value of blessings. It seems that people with chronic diseases tend to focus more on their blessings and positive experiences and enjoy beauties compared to healthy people.

This helps them overcome the long-term pain and suffering. A study on the experience of gratitude, awe, and beauty by patients with chronic diseases showed that almost half of the participants experienced the beauties of life (Bussing et al. 2014). The importance of adopting a positive attitude and being grateful for the beauties of life is always emphasized in other studies (White & Verhoef 2006).

Results of the current study showed that creating peace and balance was one of the outcomes of resilience in the elderly with chronic diseases. The participants experienced a spectrum of inner stresses when their symptoms were exacerbated; however, they could overcome inner stresses and achieve peace and balance. Researchers believe that resilience acts as a buffer for the negative physical and mental outcomes of chronic diseases (Franco et al. 2009; MacLeod et al. 2016).

People with chronic diseases deal with unpleasant thoughts permanently (Abolghasemi & Mahmoudi 2012). Through influencing thinking processes, resilience enables the patients to draw and achieve a set of resilient approaches that acts as a protective shield (Zamiri nejad et al. 2013). It was shown that resilient people represent fewer depression symptoms (Schure, Odden, & Goins 2013) , have mental health and life satisfaction, and can control their stresses (Gooding et al. 2012; Martin et al. 2015).

The participants stated that resilience, particularly during exacerbation of symptoms, enables them to prevent tension transmission to family members, maintain solidarity and cooperative atmosphere, provide opportunity to express positive and negative emotions, and preserve family unity. Chronic disease of a family member leads to change in roles, emotional turmoil, disruption of general performance of the family (Zincir et al. 2011), and changes in communications (Herzer et al. 2012). Namely, when people are not resilient cannot control their negative emotions, which leads to irritability and tension in other family members (Kamar 2015). Key characteristics of highly resilient individuals are happiness and wellbeing as well as reduced depression (MacLeod et al. 2016).

Another outcome of resilience was to overcome the disease. Participants stated that resilience was a key factor in controlling their disease. Resilience is a considerable skill for disease management. A resilient patient has high controlling potential and can handle stressful situations with optimistic attitudes and self-esteem (Mazlum 2012). In a qualitative study, older adults with chronic diseases defined resilience as an ability to overcome pain and suffers, adapt to health issues, and accept living with the chronic disease (Hassani et al. 2017).

The resilient individuals find the event controllable (Izadi-Avanji et al. 2016). Optimistic attitudes make information processing more effective, so that the individuals might adopt more active coping strategies. Through this, the activities of elderly are directed toward maintaining or promoting health or management of the disease (Fontes & Neri 2015; Seidmahmoodi 2011).

Achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease were the achievements of resilience in the elderly with chronic diseases. Understanding the outcomes of resilience in the elderly with chronic diseases created a precious insight into the ways of achieving physical, mental, and spiritual health in the patients.

The new theme found here was “the perception of beauties of life”. A methodological study is required to design and examine psychometric properties of a tool in this field. The authors suggest interventions to improve resiliency in the older adults in order to better achieve spiritual transcendence, reinforce peace and balance, and overcome the disease.

The limitation of the study was the reluctance of some participants to express their experiences. To deal with it, the researchers tried to motivate and win their support by creating good relationships and gaining their trust. Moreover, generalizable of the results of qualitative studies is a general limitation of such studies.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences (code: 93130.Oct. 2016). Before initiating the interviews, the participants were briefed about the objectives of the study and a written informed consent form was signed by each participant. The participants were ensured about confidentiality of their information throughout the study and that they could leave the study at any stage.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Kashan University of Medical Science (Grant No.: 93130).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing-Original Draft, Supervision: Fatemeh Sadat Izadi-Avanji; Collecting data: Azadeh Safa; Writing review and Editing: Mahboubeh Rezaei, Silvia Fernanda Cal; and Funding Acquisition: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Abolghasemi, S. & Mahmoudi, G., 2012. The effectiveness of stress immunization teaching on reducing stressful psychological feelings and blood glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes. World Applied Sciences Journal, 17(3), pp. 284-91.

Aléx, L., 2010. Resilience among very old men and women. Journal of Research in Nursing, 15(5), pp. 419-31. [DOI:10.1177/1744987109358836]

Aukst-Margetić, B. & Margetić, B., 2005. Religiosity and health outcomes: Review of literature. Collegium Antropologicum, 29(1), pp. 365-71. [PMID]

Bonanno, G. A., 2004. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events. American Psychologist, 59(1), p. 20. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20]

Büssing, A., et al., 2014. Experience of gratitude, awe and beauty in life among patients with multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12(1), p. 63. [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-12-63]

Elo, S. & Kyngäs, H., 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), pp. 107-15. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x]

Fontes, A. P. & Neri, A. L., 2015. Resilience in aging: Literature review. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 20(5), pp. 1475-95.[DOI:10.1590/1413-81232015205.00502014]

Franco, O. H., et al., 2009. Changing course in ageing research: The healthy ageing phenotype. Maturitas, 63(1), pp. 13-9.[DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.006]

Gooding, P. A., et al., 2012. Psychological resilience in young and older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(3), pp. 262-70. [DOI:10.1002/gps.2712]

Graneheim, U. H. & Lundman, B., 2004. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), pp. 105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001]

Hassani, P., et al., 2017. A phenomenological study on resilience of the elderly suffering from chronic disease: A qualitative study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, p. 59. [DOI:10.2147/PRBM.S121336]

Herzer, M., et al., 2010. Family functioning in the context of pediatric chronic conditions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 31(1), p. 26. [DOI:10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c7226b]

Izadi-Avanji, F. S., et al., 2017. Measurement and predictors of resilience among community-dwelling elderly in Kashan, Iran: A cross-sectional study. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 6(1), p. e36397. [DOI:10.5812/nmsjournal.36397]

Jeste, D. V., Depp, C. A. &Vahia, I. V., 2012. Successful cognitive and emotional aging. World Psychiatry, 9(2), pp. 78-84. [DOI:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00277.x] [PMID] [PMCID]

Kamar, R., Esmaieelian, N. & Mir-Mohammadi, F., 2015. [The predictor role of disability induced by pain and fear of movement in family function, in musculoskeletal patients with chronic pain (Persian)]. Thought & Behavior in Clinical Psychology, 9(35), pp. 57-66.

Kiken, L. G. & Shook, N. J., 2011. Looking up: Mindfulness increases positive judgments and reduces negativity bias. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(4), pp. 425-31. [DOI:10.1177/1948550610396585]

Lee, D. T., 2005. Quality long-term care for older people: a commentary. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(6), pp. 618-9.[DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03629.x]

Mackay, R., 2003. Family resilience and good child outcomes: An overview of the research literature. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 20, pp. 98-118.

MacLeod, S., et al., 2016. The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 37(4), pp. 266-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.014]

Mani, A., Sahraian, A., Ghetmiri, A. & Javapour, A., 2009. Psychological stressors and burden of medical conditions in older Adults: A psychosomatic approach. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, pp. 107-11.

Manning, L. K., 2014. Enduring as lived experience: Exploring the essence of spiritual resilience for women in late life. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(2), pp. 352-62. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-012-9633-6]

Martin, A. V. S., et al., 2015. Development of a new multidimensional individual and interpersonal resilience measure for older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 19(1), pp. 32-45. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2014.909383]

Mazlum B. N., et al., 2012. [Investigating the simple and multiple resilience and hardiness with problem-oriented and emotional-oriented coping styles in diabetes type 2 in yazd City (Persian)]. Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 1(2), pp. 39-49.

Roger, V. L., et al., 2012. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 125(1), pp. e2-e220. [PMID] [PMCID]

Schure, M. B., Odden, M. & Goins, R. T., 2013. The association of resilience with mental and physical health among older American Indians: The native elder care study. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 20(2), p. 27. [DOI:10.5820/aian.2002.2013.27]

Seidmahmoodi, J., Rahimi, C. & Mohamadi, N., 2011. Resiliency and religious orientation: Factors contributing to posttraumatic growth in Iranian subjects. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 6(4), p. 145. [PMID] [PMCID]

Seidman, I. 2013. Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. New York: Columbia University.

Smith, J. L. & Hollinger-Smith, L., 2015. Savoring, resilience, and psychological well-being in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 19(3), pp. 192-200. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2014.986647]

Smith, L., Webber, R. & DeFrain, J., 2013. Spiritual well-being and its relationship to resilience in young people: A mixed methods case study. SAGE Open, 3(2), pp. 1-16. [DOI:10.1177/2158244013485582]

Soroush, M., 2015. [Body image psychological characteristics and hope in women with breast cancer (Persian)]. Iranian Quarterly Journal of Breast Disease, 7(4), pp.52-63.

Southwick, S. M., et al., 2011. Resilience and mental health: Challenges across the lifespan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Speziale, H. S., Streubert, H. J. & Carpenter, D. R., 2011. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Stein, M.B., Campbell Sills, L. & Gelernter, J., 2009. Genetic variation in 5HTTLPR is associated with emotional resilience. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B, 150(7), pp. 900-6. [DOI:10.1002/ajmg.b.30916]

Ungar, M., 2011. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(1), pp. 1-17. [DOI:10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x]

White, M. & Verhoef, M., 2006. Cancer as part of the journey: the role of spirituality in the decision to decline conventional prostate cancer treatment and to use complementary and alternative medicine. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 5(2), pp. 117-22. [DOI:10.1177/1534735406288084]

Wildemuth, B. M., 2016. Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

Zamiri Nejad, S, et al., 2013. [The comparison of effectiveness of group resilience training and group cognitive therapy on decreasing rate of depression in female students who live in dorm (Persian)]. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, 4(4), pp. 631-8. [DOI:10.29252/jnkums.4.4.631]

Zincir, H., et al., 2011. Sexual lives and family function of women with family member with disability: Educational status and income level. Sexuality and Disability, 29(3), p. 197. [DOI:10.1007/s11195-011-9218-4]

“All that I see is beauty and mightiness of God” (A 67-year-old male patient with Parkinson’s disease).

Being aware and grateful for blessing was another outcome of resilience in patients with chronic diseases:

“Now that I am sick, I appreciate my blessings more than before. I thought that life meant money, but now it is different and everything around me is more important and beautiful to me” (A 80-year-old male patient with diabetes).

Resilience and coping with the hardship of a chronic disease made the participants to find daily events, so that they believed that there would be something good in their daily lives incidents:

“There is a beautiful thing in any event in a person’s life, which might be concealed from views. One of them is my blood disease. It was started with a toothache and when the doctor pulled it out, the bleeding did not stop. Then we found that I have a blood issue” (A 68-year-old male patient with leukemia).

Theme 2. Creating peace and balance

Resilience during the exacerbation of symptoms of the disease led to “creating peace and balance” in life of the elderly and their family members.

Controlling the inner stress

Due to the decrease of functional capacity and the exacerbation of symptoms, stress was one of the main issues that the elderly faced with it. The participants’ experiences showed that coping with difficult situations enabled them to better control negative psychological responses such as anger, fear, anxiety, and isolation.

“I had a severe pain in my legs overnight for the past 20 years. I could control myself through being a resilient. I learned that worrying is absurd and I need to control it” (A 67-year-old female patient with spinal stenosis).

“At first, the pain was limited to the hands and joints and I was very impatient and secluded as well. I did not like to leave home. However, I gradually managed my nerve and find a solution instead of feeling pity for myself” (A 65-year-old female patient with lupus).

Maintaining solidarity of family

Participants stated that their resilience, especially during exacerbation of the symptoms, led to “effective relationship with family members”; so that there was a lower level of stress among family members. This phenomenon is rooted in their attempts to maintain solidarity and cooperative attitudes in the family and provide a better atmosphere to express positive and negative insights. Consequently, family solidarity, peace, and balance are improved and there is less tension among the family members.

“I have been with this disease for 30 years. By being a resilient, not only I could manage my family, but there is now more sense of solidarity in the family” (A 65-year-old female patient with lupus).

Theme 3. Overcoming the disease

The participants’ statements showed that resilience is a key factor in controlling and managing the disease. Resilient patients had compliance with the treatment plan and overcame their disease by making effective communications.

Adherence to treatment

The participants mentioned that resilience enabled them to accept changes in their diet and daily life activities and experience a higher level of wellbeing.

“I have been a diabetic patient for years. The kidneys work well and I have no wound on my feet. For this, I have strict adherence to my treatment plan. I also check my blood sugar level regularly. All these enable me to have a good control over the disease and the symptoms” (An 82-year-old male patient with diabetes).

Building effective interpersonal relationships

The participants stated that their resilience led to establishment of an “effective relationship with others and medical staff”. They also added that clear and proper verbal and non-verbal interactions with others helped them to enjoy emotional, financial, and functional supports from others. Moreover, having a proper interaction with the medical staff facilitated receiving medical services.

“When I need to check my kidneys, I call my children and ask one of them to take me to the doctor. I tell them that I can also take a taxi and there would be no hard feeling if they are not available, but they are always available willfully” (A 65-year-old female patient with lupus).

“I call my family members or emergency medical services when I need a medical care. They either tell me what to do or come to help me” (A 74-year-old female patient with renal failure). The themes, categories, and sub-categories are summarized in Table 2.

4. Discussion

The findings revealed that resilience led to achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease. Achieving spiritual transcendence was one the outcomes of resilience. It seems that there is a reciprocal relationship between resilience and spirituality; so that the former enforces the latter. Resilience is developed through a process of failure and reintegration. Reintegration needs energy, which should be supplied from a spiritual source (Mackay 2003).

Spirituality provides opportunity for reinterpreting the events beyond one’s control so that the event would appear less stressful and more controllable. Moreover, considering negative events as the factors beyond one’s control creates an optimistic style (Kiken & Shook 2011). All these provide grounds for higher resilience in the face of hardships (Aukst-Margetic & Margetic 2005). A significant relationship was observed between resilience and spiritual wellbeing in the elderly (Smith, Webber, & DeFrain 2013).

Another outcome of resilience was perception of the beauties, so that the participants were able to see the beauties of relationship with others and the surrounding nature. Moreover, they could find beauties in daily life and value of blessings. It seems that people with chronic diseases tend to focus more on their blessings and positive experiences and enjoy beauties compared to healthy people.

This helps them overcome the long-term pain and suffering. A study on the experience of gratitude, awe, and beauty by patients with chronic diseases showed that almost half of the participants experienced the beauties of life (Bussing et al. 2014). The importance of adopting a positive attitude and being grateful for the beauties of life is always emphasized in other studies (White & Verhoef 2006).

Results of the current study showed that creating peace and balance was one of the outcomes of resilience in the elderly with chronic diseases. The participants experienced a spectrum of inner stresses when their symptoms were exacerbated; however, they could overcome inner stresses and achieve peace and balance. Researchers believe that resilience acts as a buffer for the negative physical and mental outcomes of chronic diseases (Franco et al. 2009; MacLeod et al. 2016).

People with chronic diseases deal with unpleasant thoughts permanently (Abolghasemi & Mahmoudi 2012). Through influencing thinking processes, resilience enables the patients to draw and achieve a set of resilient approaches that acts as a protective shield (Zamiri nejad et al. 2013). It was shown that resilient people represent fewer depression symptoms (Schure, Odden, & Goins 2013) , have mental health and life satisfaction, and can control their stresses (Gooding et al. 2012; Martin et al. 2015).

The participants stated that resilience, particularly during exacerbation of symptoms, enables them to prevent tension transmission to family members, maintain solidarity and cooperative atmosphere, provide opportunity to express positive and negative emotions, and preserve family unity. Chronic disease of a family member leads to change in roles, emotional turmoil, disruption of general performance of the family (Zincir et al. 2011), and changes in communications (Herzer et al. 2012). Namely, when people are not resilient cannot control their negative emotions, which leads to irritability and tension in other family members (Kamar 2015). Key characteristics of highly resilient individuals are happiness and wellbeing as well as reduced depression (MacLeod et al. 2016).

Another outcome of resilience was to overcome the disease. Participants stated that resilience was a key factor in controlling their disease. Resilience is a considerable skill for disease management. A resilient patient has high controlling potential and can handle stressful situations with optimistic attitudes and self-esteem (Mazlum 2012). In a qualitative study, older adults with chronic diseases defined resilience as an ability to overcome pain and suffers, adapt to health issues, and accept living with the chronic disease (Hassani et al. 2017).

The resilient individuals find the event controllable (Izadi-Avanji et al. 2016). Optimistic attitudes make information processing more effective, so that the individuals might adopt more active coping strategies. Through this, the activities of elderly are directed toward maintaining or promoting health or management of the disease (Fontes & Neri 2015; Seidmahmoodi 2011).

Achieving spiritual transcendence, creating peace and balance, and overcoming the disease were the achievements of resilience in the elderly with chronic diseases. Understanding the outcomes of resilience in the elderly with chronic diseases created a precious insight into the ways of achieving physical, mental, and spiritual health in the patients.

The new theme found here was “the perception of beauties of life”. A methodological study is required to design and examine psychometric properties of a tool in this field. The authors suggest interventions to improve resiliency in the older adults in order to better achieve spiritual transcendence, reinforce peace and balance, and overcome the disease.

The limitation of the study was the reluctance of some participants to express their experiences. To deal with it, the researchers tried to motivate and win their support by creating good relationships and gaining their trust. Moreover, generalizable of the results of qualitative studies is a general limitation of such studies.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences (code: 93130.Oct. 2016). Before initiating the interviews, the participants were briefed about the objectives of the study and a written informed consent form was signed by each participant. The participants were ensured about confidentiality of their information throughout the study and that they could leave the study at any stage.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Kashan University of Medical Science (Grant No.: 93130).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing-Original Draft, Supervision: Fatemeh Sadat Izadi-Avanji; Collecting data: Azadeh Safa; Writing review and Editing: Mahboubeh Rezaei, Silvia Fernanda Cal; and Funding Acquisition: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Abolghasemi, S. & Mahmoudi, G., 2012. The effectiveness of stress immunization teaching on reducing stressful psychological feelings and blood glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes. World Applied Sciences Journal, 17(3), pp. 284-91.

Aléx, L., 2010. Resilience among very old men and women. Journal of Research in Nursing, 15(5), pp. 419-31. [DOI:10.1177/1744987109358836]

Aukst-Margetić, B. & Margetić, B., 2005. Religiosity and health outcomes: Review of literature. Collegium Antropologicum, 29(1), pp. 365-71. [PMID]

Bonanno, G. A., 2004. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events. American Psychologist, 59(1), p. 20. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20]

Büssing, A., et al., 2014. Experience of gratitude, awe and beauty in life among patients with multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12(1), p. 63. [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-12-63]

Elo, S. & Kyngäs, H., 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), pp. 107-15. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x]

Fontes, A. P. & Neri, A. L., 2015. Resilience in aging: Literature review. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 20(5), pp. 1475-95.[DOI:10.1590/1413-81232015205.00502014]

Franco, O. H., et al., 2009. Changing course in ageing research: The healthy ageing phenotype. Maturitas, 63(1), pp. 13-9.[DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.006]

Gooding, P. A., et al., 2012. Psychological resilience in young and older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(3), pp. 262-70. [DOI:10.1002/gps.2712]

Graneheim, U. H. & Lundman, B., 2004. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), pp. 105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001]

Hassani, P., et al., 2017. A phenomenological study on resilience of the elderly suffering from chronic disease: A qualitative study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, p. 59. [DOI:10.2147/PRBM.S121336]

Herzer, M., et al., 2010. Family functioning in the context of pediatric chronic conditions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 31(1), p. 26. [DOI:10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c7226b]

Izadi-Avanji, F. S., et al., 2017. Measurement and predictors of resilience among community-dwelling elderly in Kashan, Iran: A cross-sectional study. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 6(1), p. e36397. [DOI:10.5812/nmsjournal.36397]

Jeste, D. V., Depp, C. A. &Vahia, I. V., 2012. Successful cognitive and emotional aging. World Psychiatry, 9(2), pp. 78-84. [DOI:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00277.x] [PMID] [PMCID]

Kamar, R., Esmaieelian, N. & Mir-Mohammadi, F., 2015. [The predictor role of disability induced by pain and fear of movement in family function, in musculoskeletal patients with chronic pain (Persian)]. Thought & Behavior in Clinical Psychology, 9(35), pp. 57-66.

Kiken, L. G. & Shook, N. J., 2011. Looking up: Mindfulness increases positive judgments and reduces negativity bias. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(4), pp. 425-31. [DOI:10.1177/1948550610396585]

Lee, D. T., 2005. Quality long-term care for older people: a commentary. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(6), pp. 618-9.[DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03629.x]

Mackay, R., 2003. Family resilience and good child outcomes: An overview of the research literature. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 20, pp. 98-118.

MacLeod, S., et al., 2016. The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 37(4), pp. 266-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.014]

Mani, A., Sahraian, A., Ghetmiri, A. & Javapour, A., 2009. Psychological stressors and burden of medical conditions in older Adults: A psychosomatic approach. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, pp. 107-11.

Manning, L. K., 2014. Enduring as lived experience: Exploring the essence of spiritual resilience for women in late life. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(2), pp. 352-62. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-012-9633-6]

Martin, A. V. S., et al., 2015. Development of a new multidimensional individual and interpersonal resilience measure for older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 19(1), pp. 32-45. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2014.909383]

Mazlum B. N., et al., 2012. [Investigating the simple and multiple resilience and hardiness with problem-oriented and emotional-oriented coping styles in diabetes type 2 in yazd City (Persian)]. Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 1(2), pp. 39-49.

Roger, V. L., et al., 2012. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 125(1), pp. e2-e220. [PMID] [PMCID]

Schure, M. B., Odden, M. & Goins, R. T., 2013. The association of resilience with mental and physical health among older American Indians: The native elder care study. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 20(2), p. 27. [DOI:10.5820/aian.2002.2013.27]

Seidmahmoodi, J., Rahimi, C. & Mohamadi, N., 2011. Resiliency and religious orientation: Factors contributing to posttraumatic growth in Iranian subjects. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 6(4), p. 145. [PMID] [PMCID]

Seidman, I. 2013. Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. New York: Columbia University.

Smith, J. L. & Hollinger-Smith, L., 2015. Savoring, resilience, and psychological well-being in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 19(3), pp. 192-200. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2014.986647]

Smith, L., Webber, R. & DeFrain, J., 2013. Spiritual well-being and its relationship to resilience in young people: A mixed methods case study. SAGE Open, 3(2), pp. 1-16. [DOI:10.1177/2158244013485582]

Soroush, M., 2015. [Body image psychological characteristics and hope in women with breast cancer (Persian)]. Iranian Quarterly Journal of Breast Disease, 7(4), pp.52-63.

Southwick, S. M., et al., 2011. Resilience and mental health: Challenges across the lifespan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Speziale, H. S., Streubert, H. J. & Carpenter, D. R., 2011. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Stein, M.B., Campbell Sills, L. & Gelernter, J., 2009. Genetic variation in 5HTTLPR is associated with emotional resilience. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B, 150(7), pp. 900-6. [DOI:10.1002/ajmg.b.30916]

Ungar, M., 2011. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(1), pp. 1-17. [DOI:10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x]

White, M. & Verhoef, M., 2006. Cancer as part of the journey: the role of spirituality in the decision to decline conventional prostate cancer treatment and to use complementary and alternative medicine. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 5(2), pp. 117-22. [DOI:10.1177/1534735406288084]

Wildemuth, B. M., 2016. Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

Zamiri Nejad, S, et al., 2013. [The comparison of effectiveness of group resilience training and group cognitive therapy on decreasing rate of depression in female students who live in dorm (Persian)]. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, 4(4), pp. 631-8. [DOI:10.29252/jnkums.4.4.631]

Zincir, H., et al., 2011. Sexual lives and family function of women with family member with disability: Educational status and income level. Sexuality and Disability, 29(3), p. 197. [DOI:10.1007/s11195-011-9218-4]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2018/03/28 | Accepted: 2018/08/10 | Published: 2018/11/1

Received: 2018/03/28 | Accepted: 2018/08/10 | Published: 2018/11/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |