Tue, Jul 15, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 5, Issue 4 (Autumn 2019)

JCCNC 2019, 5(4): 231-238 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khatirpasha S, Farahani-Nia M, Nikpour S, Haghani H. Puberty Health Education and Female Students’ Self-efficacy. JCCNC 2019; 5 (4) :231-238

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-202-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-202-en.html

1- Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Tehran, Iran. ,farahaninia.m@iums.ac.ir

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 627 kb]

(1680 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3558 Views)

● Adolescence is the most critical stages of a person’s life.

● Widespread psychological problems, such as depression, antisocial behaviors, and academic failure, may arise due to the dynamic changes of puberty.

● In Iran, according to the census report of 2016, >25% of the population consisted of adolescents aged 10 to 19 years, with half of them being females.

● Most girls have no basic and essential information about biopsychological conditions in puberty, as well as the required appropriate health behaviors.

● Adolescent girls require accurate and adequate information about their bodies and health.

● Education must be provided to disseminate knowledge about the biopsychosocial questions based on family, school, and public education.

Plain Language Summary

People with high self-efficacy, compared to those with low self-efficacy, select more challenging tasks that involve more effort, as well as greater goals and resilience; thus, they demonstrate better performance and experience less anxiety. Adolescent health education, as a form of educational investment, includes care that promotes mental, physical, and emotional health in adolescence and other life stages. This study aimed to determine the effect of puberty health education on the general self-efficacy of public-school female students. The relevant findings suggested that providing puberty health education was effective in promoting the students’ self-efficacy. This result could be used by healthcare providers, especially community health nurses, to support appropriate and practical training in promoting students’ self-efficacy.

● Widespread psychological problems, such as depression, antisocial behaviors, and academic failure, may arise due to the dynamic changes of puberty.

● In Iran, according to the census report of 2016, >25% of the population consisted of adolescents aged 10 to 19 years, with half of them being females.

● Most girls have no basic and essential information about biopsychological conditions in puberty, as well as the required appropriate health behaviors.

● Adolescent girls require accurate and adequate information about their bodies and health.

● Education must be provided to disseminate knowledge about the biopsychosocial questions based on family, school, and public education.

Plain Language Summary

People with high self-efficacy, compared to those with low self-efficacy, select more challenging tasks that involve more effort, as well as greater goals and resilience; thus, they demonstrate better performance and experience less anxiety. Adolescent health education, as a form of educational investment, includes care that promotes mental, physical, and emotional health in adolescence and other life stages. This study aimed to determine the effect of puberty health education on the general self-efficacy of public-school female students. The relevant findings suggested that providing puberty health education was effective in promoting the students’ self-efficacy. This result could be used by healthcare providers, especially community health nurses, to support appropriate and practical training in promoting students’ self-efficacy.

Full-Text: (1563 Views)

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a crucial period in every human’s life. It is among the most critical stages of a person’s life, linking childhood to adulthood, which involves extensive biopsychosocial changes (Martin & Steinbeck 2017). Widespread psychological problems, such as depression, antisocial behaviors, and academic failure may arise due to the dynamic changes of puberty in the brain and body glands (Heydari et al. 2015). Adolescence is among the most vital life periods, in which awareness of its natural processes and problems could lead to a successful transition to adulthood and fertility (Mohsenizadeh et al. 2017). In Iran, according to the census report of 2016, >25% of the population consisted of adolescents aged 10-19 years, with half of them being females (Iran Statistics Center 2017).

Most girls have no basic and essential information about the biopsychological changes of puberty and the required appropriate health behaviors to manage these problems. This issue probably relates to the fact that some parents fail to transfer related knowledge to their daughters properly. This could be due to the lack of knowledge as well as inadequate parental education and the lack of proper and close parent-adolescent relationships (Afghari et al. 2008). This leads to improper education, misinformation, shame, and avoiding social discussions about genital health and impeding young girls’ access to psychosocial health. In turn, it results in negative feelings about themselves and their abilities, leading to numerous other problems (Todd et al. 2015).

In many African countries, the level of girls’ awareness about adolescence and puberty matters have been reported as insufficient. Additionally, in our country, most girls lack basic and essential information about adolescence, i.e. probably due to cultural reasons (Ghahremani et al. 2008). With the onset of puberty symptoms and the lack of awareness about these changes, girls become confused and confront various challenges (Mokarie et al. 2013). The concept of self-efficacy was first defined by Albert Bandura in 1977. It is considered as a vital prerequisite for behavioral changes (Morowati Sharifabad & Rouhani Tonkaboni 2008). In Bandura’s theory, self-efficacy refers to a sense of worth, competence, and ability to cope with life. He views self-efficacy as a cognitive process, through which we develop many of our social behaviors and personality traits. Furthermore, high self-efficacy enhances the success and quality of human life (Bandura 1994).

In contrast, low self-efficacy reduces intention and impairs performance, while high self-efficacy beliefs facilitate participation in a task, task choice, effort, and performance. Consequently, self-efficacy beliefs create a basis for one’s motivation, happiness, and success (Mirzaei-Alavijeh et al. 2018). Adolescents are considered as the driving force behind society; therefore, more extreme care should be allocated to their mental health (Heydari et al. 2015). Individuals with high self-efficacy, compared to those with low self-efficacy, select more challenging tasks that involve more effort, as well as greater goals and resilience; thus, they demonstrate better performance and experience less anxiety. In general, they enjoy a better mental health status (Behrangi et al. 2017).

Self-efficacy strategies have been strongly recommended to be applied by the individuals. Moreover, education significantly affects the development of self-efficacy (Morowati Sharifabad & Rouhani Tonkaboni 2008; Reisi et al. 2017). The more people in the community are aware of diseases, the more they will strive to fight it; achieving such awareness is only possible by education (Safavi, Yahyavi & Pourrahimi 2012). Complications of puberty are easily preventable. Health education is among the fundamental and successful approaches to health promotion, i.e. effective in different ways to improve awareness and shape beliefs as well as healthy behaviors and lifestyles (Heydari et al. 2015).

Adolescent girls require accurate and adequate information about their bodies and health. Therefore, education must be provided to disseminate knowledge about the biopsychosocial questions of adolescence based on family, school, and public education (Valizadeh et al. 2017). Learning post educational sessions leads to behavioral changes; this is because after acquiring new skills or information, the learner’s attitude towards events will be modified, compared to their pre-learning conditions. Thus, their self-efficacy will be increased through verbal encouragement during training (Safavi, Yahyavi & Pourrahimi 2012). Therefore, self-efficacy structure could be used as a theoretical basis in numerous educational health programs by healthcare professionals, especially community health nurses, to promote healthy behaviors (Heydari et al. 2015).

Adolescence health education, as a form of educational investment, includes care that promotes biopsychological and emotional health. This education could be supported at three levels; in family, school, and public education, to make positive behavioral changes, raising awareness, and assisting individuals in improving their health status (Ghahremani et al. 2008). Furthermore, an educational intervention was effective in promoting puberty health self-efficacy (Heydari et al. 2015). Menstrual health studies among Iranian adolescent girls are limited. Puberty and its impact on the future of girls are of great importance; thus, through their education, information about puberty health will be provided to the society. Accordingly, the current study aimed to determine the effect of puberty health education on the self-efficacy of female students.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a quasi-experimental study with a Pre-test-Post-test and a control group design. The study population consisted of all 13- to 14-year-old female students of public schools in Ghaemshahr City, Iran. Inclusion criteria were being 13- to 14-year-old female students in Ghaemshahr public schools who have experienced one year of menstruation. Exclusion criteria were either not attending a training session or unwillingness to continue the study. After obtaining permission from the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, and Ghaemshahr Department of Education, a two-stage stratified random sampling method was applied to select the study participants.

In first step, two schools were randomly selected from the list of Ghaemshahr public primary schools among the seventh and eighth grades (sixth, seventh, & eighth grades; one school for the intervention group, another one for the control group). Accordingly, two separate schools were chosen to prevent contact between research units in each group and data contamination. Then, the researcher visited the schools and randomly sorted the intervention and control groups from the list of students per grade (seventh and eighth grades) by drawing the number required for the study sample. According to initial studies, the standard deviation of the self-efficacy score was about 8.5 (10% of the total score). Therefore, a sample size of 50 considering 5 subjects for attrition, 95% confidence, and test strength of 80% was calculated.

Initially, the educational content was provided to 10 students, and its related problems were resolved by the students, in terms of comprehension and understanding. After obtaining written informed consent from the eligible participants, the objectives and expected activities of the study were explained to them. Next, the study subjects completed the demographic form and the Sherer General Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (SGSEQ). The demographic data form included age, educational background, parents’ education and occupation, parenting status, puberty awareness, the major source of information on puberty, and individual preference for an information source. The SGSEQ was developed by Sherer et al. in 1982. It includes 17 questions in areas, such as not surrendering to problems, ability to cope with problems, ability to achieve goals and sustainability for performing activities. Each item is scored on a Likert-type scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to agree (5) strongly.

Questions 8, 3, 1, 9, 13, 15 are scored from right to left, and the rest are scored reversely (from left to right). Scores <25% (17-33.9) are considered as low self-efficacy, scores 25%-75% (34- 69.7) as moderate, those >75% (68-85) are addressed as high self-efficacy. Therefore, the maximum and minimum obtainable scores of this scale are 85 and 17, respectively (Delavar & Najafi 2013). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the SGSEQ was reported as 0.86 by Sherer et al. In Iran, Niakroei (2004) calculated the Cronbach’s alpha of the Persian version of this questionnaire as 0.78. Asgharnejad et al. investigated Iranian subjects and evaluated the psychosocial properties of SGSEQ and reported its Cronbach’s alpha as 0.83.

The external validity of the instrument was approved by the test-retest method. The questionnaire was completed by 10 characteristically-matched students as the research subjects from one of the Ghaemshahr’s schools within two weeks. These students were excluded from the study. To prevent data contamination, the study was first performed on the control group. After providing the informed consent forms, the study subjects completed the questionnaire. The control group re-completed the questionnaires three months after the intervention. This process was then repeated for the intervention group.

The intervention group training was conducted in 4 consecutive sessions, each lasting about 30 minutes. The lectures were given by the researcher according to the instructional pamphlets, i.e. validated by the nursing faculty members, using teaching aids, such as markers, boards, and slides. The content of the first session included an introduction to puberty and its associated concepts; the second session concerned physical changes and physical health in puberty (nutrition, exercise, physical activity, sleep, rest, personal health, & menstrual health).The third session included the mental changes of puberty, mental health, and self-efficacy. Finally, in the fourth session, monthly religious rituals related to menstruating and their previous learnings were reviewed in the form of question-and-answer.

The study subjects were allowed to ask questions about their ambiguities at the end of each session. After 12 weeks, the Post-test phase was performed (Sherer General Self-efficacy Questionnaire); the questionnaires were completed by the intervention and control groups. At the end of the intervention, educational content was provided to the control group members. SPSS was used for statistical analysis of the obtained data. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for data analysis. Chi-squared and Fisher’s Exact tests were used to compare the demographic characteristics of the study groups. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the data related to the general self-efficacy of Pre-test-Post-test stages. Paired Samples t-test was used to determine the difference between general self-efficacy per group at Pre-test-Post-test phases. The significance level was considered at P<0.05 in this study.

3. Results

The Mean±SD age of the students in the intervention and control groups was 13.42±0.498 and 13.66±0.478 years, respectively. The intervention and control groups were homogenous in terms of all the demographic variables, except for father’s education (P=0.001) and mother’s age (P=0.01) (Table 1).

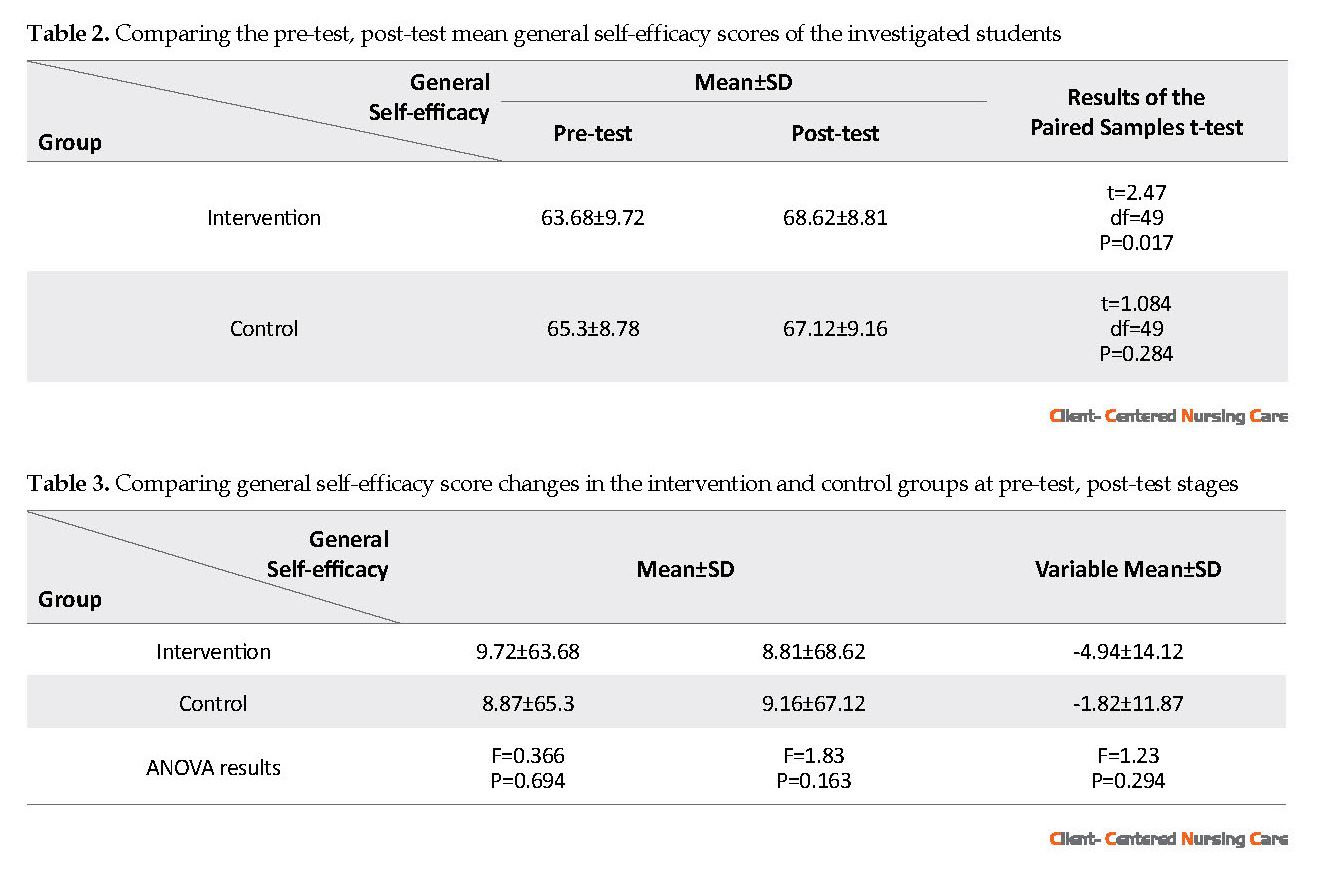

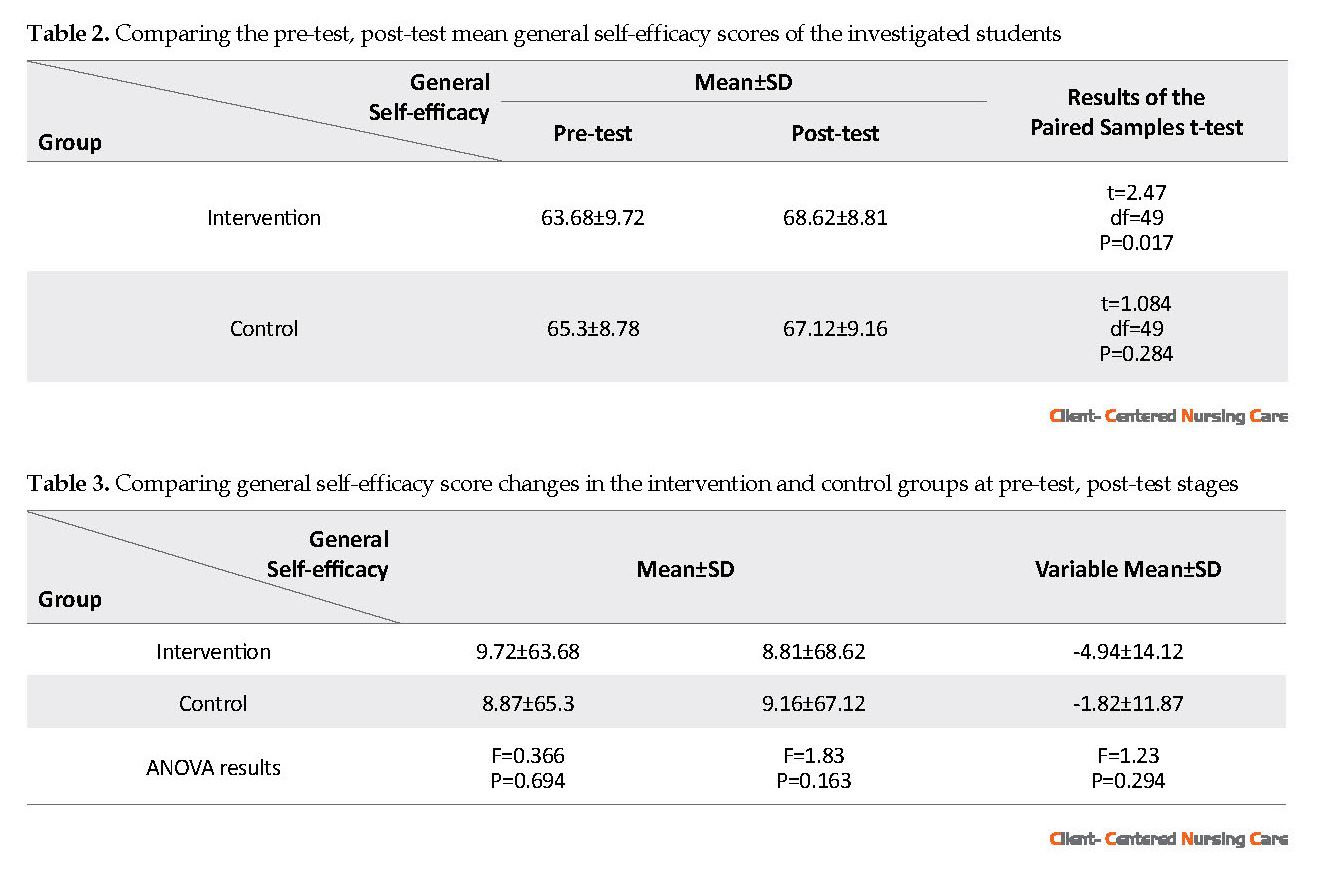

There was no significant difference between the mean self-efficacy score of the intervention (63.68±9.72) and control (65.3±8.78) groups before training (P=0.694). The difference between the mean Pre-test-Post-test scores of self-efficacy was not significant in the control group (67.12±9.16) (P=0.284). However, in the intervention group, such a difference was significant (68.62±8.81) (P=0.017) (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference between the mean changes in self-efficacy scores of the study groups before and after the training (P=0.294) (Table 3).

4. Discussion

The current study explored the effect of puberty health education on the self-efficacy of 13- to 14-year-old female students in Ghaemshahr public schools. Based on the results, the mean score of self-efficacy significantly increased in the intervention group; thus, this finding signified the positive impact of the provided training on the self-efficacy of this group. However, in the control group, the mean score difference was not statistically significant. Although no research was found to address this issue directly, the related studies have supported the effectiveness of educational programs on enhancing students’ self-efficacy.

Adolescence is a crucial period in every human’s life. It is among the most critical stages of a person’s life, linking childhood to adulthood, which involves extensive biopsychosocial changes (Martin & Steinbeck 2017). Widespread psychological problems, such as depression, antisocial behaviors, and academic failure may arise due to the dynamic changes of puberty in the brain and body glands (Heydari et al. 2015). Adolescence is among the most vital life periods, in which awareness of its natural processes and problems could lead to a successful transition to adulthood and fertility (Mohsenizadeh et al. 2017). In Iran, according to the census report of 2016, >25% of the population consisted of adolescents aged 10-19 years, with half of them being females (Iran Statistics Center 2017).

Most girls have no basic and essential information about the biopsychological changes of puberty and the required appropriate health behaviors to manage these problems. This issue probably relates to the fact that some parents fail to transfer related knowledge to their daughters properly. This could be due to the lack of knowledge as well as inadequate parental education and the lack of proper and close parent-adolescent relationships (Afghari et al. 2008). This leads to improper education, misinformation, shame, and avoiding social discussions about genital health and impeding young girls’ access to psychosocial health. In turn, it results in negative feelings about themselves and their abilities, leading to numerous other problems (Todd et al. 2015).

In many African countries, the level of girls’ awareness about adolescence and puberty matters have been reported as insufficient. Additionally, in our country, most girls lack basic and essential information about adolescence, i.e. probably due to cultural reasons (Ghahremani et al. 2008). With the onset of puberty symptoms and the lack of awareness about these changes, girls become confused and confront various challenges (Mokarie et al. 2013). The concept of self-efficacy was first defined by Albert Bandura in 1977. It is considered as a vital prerequisite for behavioral changes (Morowati Sharifabad & Rouhani Tonkaboni 2008). In Bandura’s theory, self-efficacy refers to a sense of worth, competence, and ability to cope with life. He views self-efficacy as a cognitive process, through which we develop many of our social behaviors and personality traits. Furthermore, high self-efficacy enhances the success and quality of human life (Bandura 1994).

In contrast, low self-efficacy reduces intention and impairs performance, while high self-efficacy beliefs facilitate participation in a task, task choice, effort, and performance. Consequently, self-efficacy beliefs create a basis for one’s motivation, happiness, and success (Mirzaei-Alavijeh et al. 2018). Adolescents are considered as the driving force behind society; therefore, more extreme care should be allocated to their mental health (Heydari et al. 2015). Individuals with high self-efficacy, compared to those with low self-efficacy, select more challenging tasks that involve more effort, as well as greater goals and resilience; thus, they demonstrate better performance and experience less anxiety. In general, they enjoy a better mental health status (Behrangi et al. 2017).

Self-efficacy strategies have been strongly recommended to be applied by the individuals. Moreover, education significantly affects the development of self-efficacy (Morowati Sharifabad & Rouhani Tonkaboni 2008; Reisi et al. 2017). The more people in the community are aware of diseases, the more they will strive to fight it; achieving such awareness is only possible by education (Safavi, Yahyavi & Pourrahimi 2012). Complications of puberty are easily preventable. Health education is among the fundamental and successful approaches to health promotion, i.e. effective in different ways to improve awareness and shape beliefs as well as healthy behaviors and lifestyles (Heydari et al. 2015).

Adolescent girls require accurate and adequate information about their bodies and health. Therefore, education must be provided to disseminate knowledge about the biopsychosocial questions of adolescence based on family, school, and public education (Valizadeh et al. 2017). Learning post educational sessions leads to behavioral changes; this is because after acquiring new skills or information, the learner’s attitude towards events will be modified, compared to their pre-learning conditions. Thus, their self-efficacy will be increased through verbal encouragement during training (Safavi, Yahyavi & Pourrahimi 2012). Therefore, self-efficacy structure could be used as a theoretical basis in numerous educational health programs by healthcare professionals, especially community health nurses, to promote healthy behaviors (Heydari et al. 2015).

Adolescence health education, as a form of educational investment, includes care that promotes biopsychological and emotional health. This education could be supported at three levels; in family, school, and public education, to make positive behavioral changes, raising awareness, and assisting individuals in improving their health status (Ghahremani et al. 2008). Furthermore, an educational intervention was effective in promoting puberty health self-efficacy (Heydari et al. 2015). Menstrual health studies among Iranian adolescent girls are limited. Puberty and its impact on the future of girls are of great importance; thus, through their education, information about puberty health will be provided to the society. Accordingly, the current study aimed to determine the effect of puberty health education on the self-efficacy of female students.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a quasi-experimental study with a Pre-test-Post-test and a control group design. The study population consisted of all 13- to 14-year-old female students of public schools in Ghaemshahr City, Iran. Inclusion criteria were being 13- to 14-year-old female students in Ghaemshahr public schools who have experienced one year of menstruation. Exclusion criteria were either not attending a training session or unwillingness to continue the study. After obtaining permission from the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, and Ghaemshahr Department of Education, a two-stage stratified random sampling method was applied to select the study participants.

In first step, two schools were randomly selected from the list of Ghaemshahr public primary schools among the seventh and eighth grades (sixth, seventh, & eighth grades; one school for the intervention group, another one for the control group). Accordingly, two separate schools were chosen to prevent contact between research units in each group and data contamination. Then, the researcher visited the schools and randomly sorted the intervention and control groups from the list of students per grade (seventh and eighth grades) by drawing the number required for the study sample. According to initial studies, the standard deviation of the self-efficacy score was about 8.5 (10% of the total score). Therefore, a sample size of 50 considering 5 subjects for attrition, 95% confidence, and test strength of 80% was calculated.

Initially, the educational content was provided to 10 students, and its related problems were resolved by the students, in terms of comprehension and understanding. After obtaining written informed consent from the eligible participants, the objectives and expected activities of the study were explained to them. Next, the study subjects completed the demographic form and the Sherer General Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (SGSEQ). The demographic data form included age, educational background, parents’ education and occupation, parenting status, puberty awareness, the major source of information on puberty, and individual preference for an information source. The SGSEQ was developed by Sherer et al. in 1982. It includes 17 questions in areas, such as not surrendering to problems, ability to cope with problems, ability to achieve goals and sustainability for performing activities. Each item is scored on a Likert-type scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to agree (5) strongly.

Questions 8, 3, 1, 9, 13, 15 are scored from right to left, and the rest are scored reversely (from left to right). Scores <25% (17-33.9) are considered as low self-efficacy, scores 25%-75% (34- 69.7) as moderate, those >75% (68-85) are addressed as high self-efficacy. Therefore, the maximum and minimum obtainable scores of this scale are 85 and 17, respectively (Delavar & Najafi 2013). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the SGSEQ was reported as 0.86 by Sherer et al. In Iran, Niakroei (2004) calculated the Cronbach’s alpha of the Persian version of this questionnaire as 0.78. Asgharnejad et al. investigated Iranian subjects and evaluated the psychosocial properties of SGSEQ and reported its Cronbach’s alpha as 0.83.

The external validity of the instrument was approved by the test-retest method. The questionnaire was completed by 10 characteristically-matched students as the research subjects from one of the Ghaemshahr’s schools within two weeks. These students were excluded from the study. To prevent data contamination, the study was first performed on the control group. After providing the informed consent forms, the study subjects completed the questionnaire. The control group re-completed the questionnaires three months after the intervention. This process was then repeated for the intervention group.

The intervention group training was conducted in 4 consecutive sessions, each lasting about 30 minutes. The lectures were given by the researcher according to the instructional pamphlets, i.e. validated by the nursing faculty members, using teaching aids, such as markers, boards, and slides. The content of the first session included an introduction to puberty and its associated concepts; the second session concerned physical changes and physical health in puberty (nutrition, exercise, physical activity, sleep, rest, personal health, & menstrual health).The third session included the mental changes of puberty, mental health, and self-efficacy. Finally, in the fourth session, monthly religious rituals related to menstruating and their previous learnings were reviewed in the form of question-and-answer.

The study subjects were allowed to ask questions about their ambiguities at the end of each session. After 12 weeks, the Post-test phase was performed (Sherer General Self-efficacy Questionnaire); the questionnaires were completed by the intervention and control groups. At the end of the intervention, educational content was provided to the control group members. SPSS was used for statistical analysis of the obtained data. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for data analysis. Chi-squared and Fisher’s Exact tests were used to compare the demographic characteristics of the study groups. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the data related to the general self-efficacy of Pre-test-Post-test stages. Paired Samples t-test was used to determine the difference between general self-efficacy per group at Pre-test-Post-test phases. The significance level was considered at P<0.05 in this study.

3. Results

The Mean±SD age of the students in the intervention and control groups was 13.42±0.498 and 13.66±0.478 years, respectively. The intervention and control groups were homogenous in terms of all the demographic variables, except for father’s education (P=0.001) and mother’s age (P=0.01) (Table 1).

There was no significant difference between the mean self-efficacy score of the intervention (63.68±9.72) and control (65.3±8.78) groups before training (P=0.694). The difference between the mean Pre-test-Post-test scores of self-efficacy was not significant in the control group (67.12±9.16) (P=0.284). However, in the intervention group, such a difference was significant (68.62±8.81) (P=0.017) (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference between the mean changes in self-efficacy scores of the study groups before and after the training (P=0.294) (Table 3).

4. Discussion

The current study explored the effect of puberty health education on the self-efficacy of 13- to 14-year-old female students in Ghaemshahr public schools. Based on the results, the mean score of self-efficacy significantly increased in the intervention group; thus, this finding signified the positive impact of the provided training on the self-efficacy of this group. However, in the control group, the mean score difference was not statistically significant. Although no research was found to address this issue directly, the related studies have supported the effectiveness of educational programs on enhancing students’ self-efficacy.

A study in India suggested that presenting an intervention approach to girls’ health education in the field of menstrual health management significantly modified their knowledge and performance (Dongre et al. 2007). Furthermore, education was suggested to improve nutritional performance in trained adolescent students (Schmidt 2010). Similar studies have also highlighted the impact of puberty health education on raising girls’ awareness and performance (Majlessi et al. 2012; Kalantary et al. 2013; Alimoradi & Simbar 2014; Naisi et al. 2016).

On the other hand, a study about the effect of puberty health education on mothers and their female students’ knowledge and performance revealed that girls’ direct education only increased their puberty health score; however, it could not affect their performance. Accordingly, to promote adolescent girls’ awareness of puberty health, education to mothers could be a more effective method than directly training adolescent girls (Afsari et al. 2017). Moreover, educating adolescents on nutritional performance and physical activities, like exercise, positively affected their self-efficacy (Safavi, Yahyavi & Pourrahimi 2012). Another study indicated that educational interventions were associated with significant positive changes in the health behavior of female adolescent students (Abedi et al. 2015).

On the other hand, a study about the effect of puberty health education on mothers and their female students’ knowledge and performance revealed that girls’ direct education only increased their puberty health score; however, it could not affect their performance. Accordingly, to promote adolescent girls’ awareness of puberty health, education to mothers could be a more effective method than directly training adolescent girls (Afsari et al. 2017). Moreover, educating adolescents on nutritional performance and physical activities, like exercise, positively affected their self-efficacy (Safavi, Yahyavi & Pourrahimi 2012). Another study indicated that educational interventions were associated with significant positive changes in the health behavior of female adolescent students (Abedi et al. 2015).

Health education through lectures and educational packages in a study was effective in advancing the self-efficacy of 11- to 9-year-old students during puberty (Heydari et al. 2015). A study investigated the impact of an educational program on the health promotion of adolescent girls’ physical health. The relevant data indicated that educational intervention positively improved students’ performance during adolescence (Shirzadi et al. 2015).

A study on the effectiveness of group education on girls’ self-efficacy indicated that spiritual education plays an important role in enhancing students’ mental health. The authors concluded that promoting self-efficacy is a key step in achieving optimal mental health (Safa Chaleshtari et al. 2017). According to another study, self-efficacy strongly affects health behaviors; this is because high self-efficacy increases ability, capability, competence, and adequacy. The authors have emphasized that self-efficacy is the foundation of behavior that should be given special attention; this is because it is required to understand all measures that should be taken and the causes of that behavior, as well as enabling the person to perform that particular behavior (Ramezankhani et al. 2011). Besides, educational intervention positively and significantly impacts the perceived self-efficacy and interpersonal relations and reduces existing barriers to physical activity and performance improvement (Teymouri et al. 2007). This finding indicates the importance of self-efficacy in performing health behaviors.

According to the present study results, there was no significant difference in the self-efficacy between the intervention and control groups. Such data might be associated with the three months’ time interval between conducting training and post-tests; however, self-efficacy significantly increased in the test group after providing the study intervention. The results of other mentioned investigations also revealed that puberty health education significantly increased students’ self-efficacy and could lead to positive health behaviors in adolescents (Safavi, Yahyavi & Pourrahimi 2012).

Health habits and patterns are formed in childhood and adolescence, and proper health behaviors in these ages affect future health and well-being. Furthermore, the school environment plays a critical role in conveying healthy or unhealthy habits; accordingly, the necessity of providing educational programs to change the habits of health practices is emphasized more than ever. Therefore, healthcare providers, including community health nurses, could provide puberty health promotion training programs to increase self-efficacy in these groups of girls.

To lead a healthy and vibrant life, health education programs should be included in school health programs, and self-efficacy enhancement must be planned from an early age. Students are the best messengers of health; they could assist their parents in fostering a lifestyle that enhances their sense of responsibility for their health and that of their children and to strive to lead their inappropriate health behaviors towards healthy ones. It is suggested that future studies extend training time and education be conducted by a qualified person, preferably a community health nurse, in the form of a major course.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of IUMS (Code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1397.342). The current study was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) (Code: IRCT20180714040461N1). All the investigated students provided a signed informed consent form.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the MSc. thesis of the first author, Simin Khatirpasha, in the Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery of IUMS.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Soghra Nikpoure, Marhamat Farahaninia, Simin Khatirpasha; Methodology: Soghra Nikpoure, Marhamat Farahaninia, Simin Khatirpasha, Hamid Haghani; Investigation: Simin Khatirpasha; Writing the original draft and reviewing and editing the manuscript: Marhamat Farahaninia, Simin Khatirpasha; Supervision: Marhamat Farahaninia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the Vice Chancellor for Research of Iran University of Medical Sciences for the financial support, the officials of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Ghaemshahr Education Department, and the students who participated in this study and all those who have contributed to this research.

References

Abedi, R., et al. 2015. [Determining the effect of an educational intervention based on constructs of Health Belief Model on Promotion of Physical Puberty Health among student girls (Persian)]. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences, 22(137), pp. 84-94. http://rjms.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4078-en.html

Afghari, A., et al. 2008. Effects of puberty health education on 10-14 year-old girls’ knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 3(1), pp. 38-41. http://ijnmr.mui.ac.ir/index.php/ijnmr/article/view/37/37

Afsari, A., et al. 2017. The effects of educating mothers and girls on the girls’ attitudes toward puberty health: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 29(2), p. 20150043. [DOI:10.1515/ijamh-2015-0043] [PMID]

Alimoradi, Z. & Simbar, M., 2014. [Puberty health education for iranian adolescent girls: Challenges and priorities to design school-based interventions for mothers and daughters (Persian)]. Payesh, 13(5), pp. 621-36. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=393379

Bandura, A., 1994. Self-efficacy. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior, 4, pp. 71-81. https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/BanEncy.html

Behrangi, M. R., et al. 2017. [Application of Bandura’s self-efficacy theory with mathematics education management model: A new strategy for self-efficacy development in high school secondary school students (Persian)]. Journal of Managing Education in Organizations, 5(2), pp. 9-44. http://journalieaa.ir/article-1-80-fa.html

Delavar, A. & Najafi, M., 2013. [The psychometric properties of the general self efficacy scale among university staff (Persian)]. Educational Measurement, 4(12), pp. 87-104. https://www.magiran.com/paper/1169836/?lang=en

Dongre, A., Deshmukh, P. & Garg, B., 2007. The effect of community-based health education intervention on management of menstrual hygiene among rural Indian adolescent girls. World Health & Population, 9(3), pp. 48-54. [DOI:10.12927/whp.2007.19303] [PMID]

Ghahremani, L., et al. 2008. [Effects of puberty health education on health behavior of secondary school girl students in Chabahar city (Persian)]. Iranian South Medical Journal, 11(1), pp. 61-8. https://www.magiran.com/paper/595407?lang=en

Heydari, M., et al. 2015. [The study of comparison of two educational methods of lecture and training package on self-efficacy 9-12 years old girls students in relation with adolescent health (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research, 10(1), pp. 1-12. http://ijnr.ir/article-1-1476-en.html

Iran Statistics Center, 2017. Statistics Centerof Iran, Selected results of population and housing census. https://www.amar.org.ir/english

Kalantary, S., et al. 2013. [Puberty and sex education to girls: Experiences of Gorganians’ mothers (Persian)]. Journal of Health Promotion Management, 2(3), pp. 74-90. http://jhpm.ir/article-1-90-en.html

Majlessi, F., 2012. [The impact of lecture and educational package methods in knowledge and attitude of teenage girls on puberty health (Persian)]. Bimonthly Journal of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, 15(4), pp. 327-32. https://sites.kowsarpub.com/hmj/articles/88528.html

Martin, A. J. & Steinbeck, K., 2017. The role of puberty in students’ academic motivation and achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 53, pp. 37-46. [DOI:10.1016/j.lindif.2016.11.003]

Mirzaei-Alavijeh, M., et al. 2018. [Academic self-efficacy and its relationship with academic variables among Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences students: A cross sectional study (Persian)]. Pajouhan Scientific Journal, 16(2), pp. 28-34. http://psj.umsha.ac.ir/article-1-380-en.html

Mohsenizadeh, M., Ebadinejad , Z. & Moudi, A., 2017. [Effect of puberty health education on awareness health assessment and general health of females studying at junior high schools of Ghaen city (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research, 12(2), pp. 28-37. http://ijnr.ir/browse.php?a_id=1762&sid=1&slc_lang=en

Mokarie, H., et al. 2013. [The impact of puberty health education on self concept of adolescents (Persian)]. Iranian Journal Of Nursing Research, 8(3), pp. 47-57. http://ijnr.ir/article-1-1259-en.html

Morowati Sharifabad, M. & Rouhani Tonkaboni, N., 2008. [The relationship between perceived benefits/barriers of self-care behaviors and self management in diabetic patient (Persian)]. Hayat, 13(1), pp. 17-27. http://hayat.tums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=183&sid=1&slc_lang=fa

Naisi, N., et al. 2016. Knowledge, attitude and performance of K-9 girl students of Ilam city toward puberty health in 2013-14. Scientific Journal Of Ilam University Of Medical Sciences, 24(1), pp. 28-34. [DOI:10.18869/acadpub.sjimu.24.1.28]

Ramezankhani, A., et al. 2011. [Relationship between health belief model constructs and DMFT among five-grade boy students in the primary school in Dezfool (Persian)]. Jundishapur Scientific Medical Journal, 10(2), pp. 221-8. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=201201

Reisi, M., 2017. Effects of an educational intervention on self-care and metabolic control in patients with type II diabetes. Journal of Client-Centered Nursing Care, 3(3), pp. 205-14. [DOI:10.32598/jccnc.3.3.205]

Safa Chaleshtari, K., Sharifi, T. & Ghasemi Pirbalooti, M., 2017. [A study of the effectiveness of group spiritual intelligence training on self-efficacy and social responsibility of secondary school girls in Shahrekord (Persian)]. Social Behavior Research & Health, 1(2), pp. 81-90. http://sbrh.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-34-en.html

Safavi, M., Yahyavi, H. & Pourrahimi, M., 2012. [Impact of dietary behaviors and exercise activities education on the self-efficacy of middle school students (Persian)]. Medical Science Journal of Islamic Azad Univesity, 22(2), pp. 143-51. http://tmuj.iautmu.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=570&sid=1&slc_lang=en

Schmidt, R. L. 2010. Impact of nutrition education on dietary habits of female high school students [MSc. thesis]. Ypsilanti: Eastern Michigan University. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8749/c39f81617aa15ea2dfcc59a82869ce28be8b.pdf

Shirzadi, S., et al. 2015. Effects of education based on focus group discussions on menstrual health behaviors of female adolescents in boarding centers of the welfare organization, Tehran, Iran. Journal of Education Community Health, 1(4), pp. 1-10. [DOI:10.20286/jech-01041]

Teymouri, P., Niknami, S. & Ghofranipour, F., 2007. [Effects of a school-based intervention on the basis of pender’s health promotion model to improve physical activity among high school girls (Persian)]. Armaghane Danesh, 12(2), pp. 47-59. http://armaghanj.yums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-39-65&slc_lang=en&sid=1

Todd, A. S., et al. 2015. Overweight and obese adolescent girls: The importance of promoting sensible eating and activity behaviors from the start of the adolescent period. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 12(2), pp. 2306-29. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph120202306] [PMID] [PMCID]

Valizadeh, S., et al. 2017. Educating mothers and girls about knowledge and practices toward puberty hygiene in tabriz, iran: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 19(2), p. e28593. [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.28593]

A study on the effectiveness of group education on girls’ self-efficacy indicated that spiritual education plays an important role in enhancing students’ mental health. The authors concluded that promoting self-efficacy is a key step in achieving optimal mental health (Safa Chaleshtari et al. 2017). According to another study, self-efficacy strongly affects health behaviors; this is because high self-efficacy increases ability, capability, competence, and adequacy. The authors have emphasized that self-efficacy is the foundation of behavior that should be given special attention; this is because it is required to understand all measures that should be taken and the causes of that behavior, as well as enabling the person to perform that particular behavior (Ramezankhani et al. 2011). Besides, educational intervention positively and significantly impacts the perceived self-efficacy and interpersonal relations and reduces existing barriers to physical activity and performance improvement (Teymouri et al. 2007). This finding indicates the importance of self-efficacy in performing health behaviors.

According to the present study results, there was no significant difference in the self-efficacy between the intervention and control groups. Such data might be associated with the three months’ time interval between conducting training and post-tests; however, self-efficacy significantly increased in the test group after providing the study intervention. The results of other mentioned investigations also revealed that puberty health education significantly increased students’ self-efficacy and could lead to positive health behaviors in adolescents (Safavi, Yahyavi & Pourrahimi 2012).

Health habits and patterns are formed in childhood and adolescence, and proper health behaviors in these ages affect future health and well-being. Furthermore, the school environment plays a critical role in conveying healthy or unhealthy habits; accordingly, the necessity of providing educational programs to change the habits of health practices is emphasized more than ever. Therefore, healthcare providers, including community health nurses, could provide puberty health promotion training programs to increase self-efficacy in these groups of girls.

To lead a healthy and vibrant life, health education programs should be included in school health programs, and self-efficacy enhancement must be planned from an early age. Students are the best messengers of health; they could assist their parents in fostering a lifestyle that enhances their sense of responsibility for their health and that of their children and to strive to lead their inappropriate health behaviors towards healthy ones. It is suggested that future studies extend training time and education be conducted by a qualified person, preferably a community health nurse, in the form of a major course.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of IUMS (Code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1397.342). The current study was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) (Code: IRCT20180714040461N1). All the investigated students provided a signed informed consent form.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the MSc. thesis of the first author, Simin Khatirpasha, in the Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery of IUMS.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Soghra Nikpoure, Marhamat Farahaninia, Simin Khatirpasha; Methodology: Soghra Nikpoure, Marhamat Farahaninia, Simin Khatirpasha, Hamid Haghani; Investigation: Simin Khatirpasha; Writing the original draft and reviewing and editing the manuscript: Marhamat Farahaninia, Simin Khatirpasha; Supervision: Marhamat Farahaninia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the Vice Chancellor for Research of Iran University of Medical Sciences for the financial support, the officials of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Ghaemshahr Education Department, and the students who participated in this study and all those who have contributed to this research.

References

Abedi, R., et al. 2015. [Determining the effect of an educational intervention based on constructs of Health Belief Model on Promotion of Physical Puberty Health among student girls (Persian)]. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences, 22(137), pp. 84-94. http://rjms.iums.ac.ir/article-1-4078-en.html

Afghari, A., et al. 2008. Effects of puberty health education on 10-14 year-old girls’ knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 3(1), pp. 38-41. http://ijnmr.mui.ac.ir/index.php/ijnmr/article/view/37/37

Afsari, A., et al. 2017. The effects of educating mothers and girls on the girls’ attitudes toward puberty health: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 29(2), p. 20150043. [DOI:10.1515/ijamh-2015-0043] [PMID]

Alimoradi, Z. & Simbar, M., 2014. [Puberty health education for iranian adolescent girls: Challenges and priorities to design school-based interventions for mothers and daughters (Persian)]. Payesh, 13(5), pp. 621-36. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=393379

Bandura, A., 1994. Self-efficacy. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior, 4, pp. 71-81. https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/BanEncy.html

Behrangi, M. R., et al. 2017. [Application of Bandura’s self-efficacy theory with mathematics education management model: A new strategy for self-efficacy development in high school secondary school students (Persian)]. Journal of Managing Education in Organizations, 5(2), pp. 9-44. http://journalieaa.ir/article-1-80-fa.html

Delavar, A. & Najafi, M., 2013. [The psychometric properties of the general self efficacy scale among university staff (Persian)]. Educational Measurement, 4(12), pp. 87-104. https://www.magiran.com/paper/1169836/?lang=en

Dongre, A., Deshmukh, P. & Garg, B., 2007. The effect of community-based health education intervention on management of menstrual hygiene among rural Indian adolescent girls. World Health & Population, 9(3), pp. 48-54. [DOI:10.12927/whp.2007.19303] [PMID]

Ghahremani, L., et al. 2008. [Effects of puberty health education on health behavior of secondary school girl students in Chabahar city (Persian)]. Iranian South Medical Journal, 11(1), pp. 61-8. https://www.magiran.com/paper/595407?lang=en

Heydari, M., et al. 2015. [The study of comparison of two educational methods of lecture and training package on self-efficacy 9-12 years old girls students in relation with adolescent health (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research, 10(1), pp. 1-12. http://ijnr.ir/article-1-1476-en.html

Iran Statistics Center, 2017. Statistics Centerof Iran, Selected results of population and housing census. https://www.amar.org.ir/english

Kalantary, S., et al. 2013. [Puberty and sex education to girls: Experiences of Gorganians’ mothers (Persian)]. Journal of Health Promotion Management, 2(3), pp. 74-90. http://jhpm.ir/article-1-90-en.html

Majlessi, F., 2012. [The impact of lecture and educational package methods in knowledge and attitude of teenage girls on puberty health (Persian)]. Bimonthly Journal of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, 15(4), pp. 327-32. https://sites.kowsarpub.com/hmj/articles/88528.html

Martin, A. J. & Steinbeck, K., 2017. The role of puberty in students’ academic motivation and achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 53, pp. 37-46. [DOI:10.1016/j.lindif.2016.11.003]

Mirzaei-Alavijeh, M., et al. 2018. [Academic self-efficacy and its relationship with academic variables among Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences students: A cross sectional study (Persian)]. Pajouhan Scientific Journal, 16(2), pp. 28-34. http://psj.umsha.ac.ir/article-1-380-en.html

Mohsenizadeh, M., Ebadinejad , Z. & Moudi, A., 2017. [Effect of puberty health education on awareness health assessment and general health of females studying at junior high schools of Ghaen city (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research, 12(2), pp. 28-37. http://ijnr.ir/browse.php?a_id=1762&sid=1&slc_lang=en

Mokarie, H., et al. 2013. [The impact of puberty health education on self concept of adolescents (Persian)]. Iranian Journal Of Nursing Research, 8(3), pp. 47-57. http://ijnr.ir/article-1-1259-en.html

Morowati Sharifabad, M. & Rouhani Tonkaboni, N., 2008. [The relationship between perceived benefits/barriers of self-care behaviors and self management in diabetic patient (Persian)]. Hayat, 13(1), pp. 17-27. http://hayat.tums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=183&sid=1&slc_lang=fa

Naisi, N., et al. 2016. Knowledge, attitude and performance of K-9 girl students of Ilam city toward puberty health in 2013-14. Scientific Journal Of Ilam University Of Medical Sciences, 24(1), pp. 28-34. [DOI:10.18869/acadpub.sjimu.24.1.28]

Ramezankhani, A., et al. 2011. [Relationship between health belief model constructs and DMFT among five-grade boy students in the primary school in Dezfool (Persian)]. Jundishapur Scientific Medical Journal, 10(2), pp. 221-8. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=201201

Reisi, M., 2017. Effects of an educational intervention on self-care and metabolic control in patients with type II diabetes. Journal of Client-Centered Nursing Care, 3(3), pp. 205-14. [DOI:10.32598/jccnc.3.3.205]

Safa Chaleshtari, K., Sharifi, T. & Ghasemi Pirbalooti, M., 2017. [A study of the effectiveness of group spiritual intelligence training on self-efficacy and social responsibility of secondary school girls in Shahrekord (Persian)]. Social Behavior Research & Health, 1(2), pp. 81-90. http://sbrh.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-34-en.html

Safavi, M., Yahyavi, H. & Pourrahimi, M., 2012. [Impact of dietary behaviors and exercise activities education on the self-efficacy of middle school students (Persian)]. Medical Science Journal of Islamic Azad Univesity, 22(2), pp. 143-51. http://tmuj.iautmu.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=570&sid=1&slc_lang=en

Schmidt, R. L. 2010. Impact of nutrition education on dietary habits of female high school students [MSc. thesis]. Ypsilanti: Eastern Michigan University. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8749/c39f81617aa15ea2dfcc59a82869ce28be8b.pdf

Shirzadi, S., et al. 2015. Effects of education based on focus group discussions on menstrual health behaviors of female adolescents in boarding centers of the welfare organization, Tehran, Iran. Journal of Education Community Health, 1(4), pp. 1-10. [DOI:10.20286/jech-01041]

Teymouri, P., Niknami, S. & Ghofranipour, F., 2007. [Effects of a school-based intervention on the basis of pender’s health promotion model to improve physical activity among high school girls (Persian)]. Armaghane Danesh, 12(2), pp. 47-59. http://armaghanj.yums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-39-65&slc_lang=en&sid=1

Todd, A. S., et al. 2015. Overweight and obese adolescent girls: The importance of promoting sensible eating and activity behaviors from the start of the adolescent period. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 12(2), pp. 2306-29. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph120202306] [PMID] [PMCID]

Valizadeh, S., et al. 2017. Educating mothers and girls about knowledge and practices toward puberty hygiene in tabriz, iran: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 19(2), p. e28593. [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.28593]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2019/02/19 | Accepted: 2019/09/2 | Published: 2020/06/1

Received: 2019/02/19 | Accepted: 2019/09/2 | Published: 2020/06/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |