Sat, Oct 18, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 5, Issue 3 (Summer 2019)

JCCNC 2019, 5(3): 147-156 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee A, Akhalaghi-Yazdi R, Hojati Sayah M. Investigating Gestalt-based Play Therapy on Anxiety and Loneliness in Female Labour Children With Sexual Abuse: A Single Case Research Design (SCRD). JCCNC 2019; 5 (3) :147-156

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-228-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-228-en.html

1- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Khatam University, Tehran, Iran. , a.khodabakhshid@khatam.ac.ir

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Khatam University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Khatam University, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Gestalt play therapy, Sexual harassment, Labor children, Loneliness, Anxiety, Single-case research

Full-Text [PDF 608 kb]

(2388 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4798 Views)

• Investigating the psychological problems of labor, children should be targeted by psychologists and counselors.

• The immigrant population is largely identified as an illegal immigrant workforce and suffers from serious social harm.

• Informal education and play therapy reduce psychological traumas, such as anxiety and loneliness in children.

• The case study method contributes to an in-depth understanding of therapeutic changes.

Plain Language Summary

In 2015, according to the United Nations Office for Refugees (UNHCR), the number of displaced persons reached 52 million. These families, who migrate to other countries because of war or economic refugees, work illegally for the rest of their lives. Meanwhile, their children also work, which is inappropriate for their development and adds to the problems of the host community. This study examined 3 sexually-abused Afghan female labor children. Gestalt play therapy helped these children alleviate anxiety and loneliness caused by their psychological problems. Informal education and play therapy in schools can help reduce the psychosocial problems of children.

• The immigrant population is largely identified as an illegal immigrant workforce and suffers from serious social harm.

• Informal education and play therapy reduce psychological traumas, such as anxiety and loneliness in children.

• The case study method contributes to an in-depth understanding of therapeutic changes.

Plain Language Summary

In 2015, according to the United Nations Office for Refugees (UNHCR), the number of displaced persons reached 52 million. These families, who migrate to other countries because of war or economic refugees, work illegally for the rest of their lives. Meanwhile, their children also work, which is inappropriate for their development and adds to the problems of the host community. This study examined 3 sexually-abused Afghan female labor children. Gestalt play therapy helped these children alleviate anxiety and loneliness caused by their psychological problems. Informal education and play therapy in schools can help reduce the psychosocial problems of children.

Full-Text: (2238 Views)

1. Introduction

Childhood is a crucial period and significantly affects human life. The presence of social harm and problems in every society puts children at greater risk than others and endangers their psychosocial health (Khairi-hassan, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Taghvaee 2016).

According to the international labor convention, child labor includes all children aged <18 years working in hazardous jobs or activities. Children's work is not defined by the activity, but as its effect on the child. The work or activity that the child does should not interfere with his/her education or pose any threat to his/her health (United Nations, 2019). According to United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) statistics, 218 million 5-17-year-old children are working, of whom 125 million are victims of hardship, and more than half (73 million children) are working in onerous physical conditions. Based on more accurate statistics, nearly half (72.1 million) of these children are living in Africa, 62.1 million in Asia and Oceania, 10.7 million in North and South America, 1.2 million in the United Arab Emirates, and 5.5 million children are working in Europe and Central Asia (Khakshour et al. 2015).

The majority of the labor force in Iran are Afghan children. Iran has 979/400 Afghan and Iraqi refugees. Iran ranks fourth in terms of accepting immigrants from war-torn countries (Refugees UNHCo, 2016). Forced migration means living in an environment where individuals continue to live with the problems. Meanwhile, their children also work, which is inappropriate for their age and adds to the problems of the host community (khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Falsafinejad & Gholeinejad 2019).

In Iran, according to unofficial statistics, about 35000 children are working in Tehran Province, Iran (Khairi-hassan, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Taghvaee 2016). The problems of labor children, in addition to human, moral, and socioeconomic dimensions, have another important aspect from the viewpoint of those who look at social issues from a health perspective (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Ashrafi & Hemmatimanesh 2013; Maccmillan et al. 2013).

The health problems of these children have affected their psychosocial health status, i.e. significantly worse than that of their peers in the relative terms (Beazzley 2015; Libório & Ungar 2010). Furthermore, the mental health of these children (in the early years of childhood) is severely damaged and leads them to low self-esteem and anxiety.

Many of these children are victims of sexual violence and are even sold as sexual slaves in exchange for money (Beazley et al. 2015; Choi, Yeoh & Lam 2019). Many governmental and nongovernmental organizations consider counseling, supportive, educational, and therapeutic services to address the biopsychosocial problems of these children (Khairi-hassan, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Taghvaee 2016; Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, et al. 2016). Children communicate very well through art therapy, play therapy, and theater-based interventions (Blom 2006).

Play therapy is a structured therapy designed based on different theories and treatments appropriate to the learning process of children and their healthy relationship with other children (Landreth 2012). Play therapy is widely used for children and adolescents who are victims of violence and sexual abuse. For example, Harvey et al. in their meta-analysis study, have revealed that play therapy is an effective measure to reduce the problems of children and multiple psychological symptoms (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Mokhtari & Rasstak 2018).

Gestalt play therapy comprises exercises involving all 5 senses of children to express emotions properly. It is a humanist and process-oriented form of therapy (Blom 2006). Violet Oaklander is considered to be the founder of Gestalt play therapy. Oaklander (1997) describes Gestalt therapy by considering that several theoretical principles of gestalt therapy, such as relationship, organismic self-regulation, contact boundary disturbances, awareness, and experience and resistance affect therapeutic work with children (Oaklander 1997; Blom 2006).

Given the verbal, cognitive, and social capacities of children, Gestalt play therapy is an appropriate intervention for them. In addition, considering the specific features of Gestalt play therapy, such as trying to inform the children of their inner and outer moods, having proper physical feedback, as well as expressing their emotions, it is expected that Gestalt play therapy desirably improve the loneliness and anxiety of these children (Harvey & Tylor 2010; Denton 2014). This theory tries to enable children to be fully present in a certain position using their senses, such as sight, hearing, and smell, which mediate between them and their environment; identifying what is being done and knowing how to perform it is the same process of maintaining contact with the environment. In this theory, some games are played with children to become aware of their senses and express their emotions, leading to the integration of personality, choice, and change (Landreth 2012; Constantinou 2007).

Additionally, emotions, such as guilt and shame in children and adolescents who were the victims of violence and sexual abuse, could be treated through Gestalt play therapy. These feelings create anger, loneliness, despair, and misery in them (Denton 2014). Besides, Gestalt play therapy could effectively decrease anxiety in children hospitalized with cancer (Constantinou 2007). In this regard, some researchers have used Gestalt play therapy to promote social adjustment and self-esteem in students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). They have concluded that this type of play therapy helps children to gain a better knowledge of themselves and to have a mutual understanding of others’ emotions (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Mokhtari & Rasstak 2018). Accordingly, the current study investigated the effect of Gestalt play therapy on anxiety and loneliness among Afghan female labor children with a sexual abuse history.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study was carried out using a Single Case Research Design (SCRD) of the AB model with two time periods. Period A was a baseline in which the study subjects’ behaviors were precisely defined; then, they were observed under normal conditions for some time. Period B was an experimental phase in which the independent variable was manipulated or entered to determine its effect on the behaviors. Finally, the subjects’ scores in each period were plotted and compared. After one month, the dependent variable was again evaluated, i.e. called the follow-up phase (Rezaee-Khoshkzari & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee 2018).

The study population consisted of all sexually-abused Afghan children aged 8-11 years in Karaj City, Iran, in 2018. Three 8-11-year-old female labor children with sexual abuse histories supported by Imam Ali Society (AS) were selected using a random sampling method. Data were collected using the Child Abuse Scale (CAS), Asher Loneliness Scale (ALS), and Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS).

CAS was designed by Malik and Shah (2007) to assess the types and severity of child abuse. It consists of 34 items covering three types of abuse: a. Physical abuse with 4 items; b. Emotional abuse with 14 items; c. Emotional abuse with 12 items; and d. Physical neglect with 4 items. These statements were written in the form of scale along with a 4-point rating scale with the categories of “never”, “seldom”, “often”, and “always”. Scale’s’ total scores ranged from 1 to 4. The scoring range for CAS was 34-136. Cut-off scores for the scale were determined by analyzing the study subjects, and the criterion was one standard deviation plus and one standard deviation below the mean scores of the study subjects. A score <54 was determined as an indicator of mild abuse; 55-65 as moderate abuse and a score of ≥66 determined severe abuse. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was also computed, and it proved to be a highly internally consistent and reliable measure of child abuse (r=0.92) (Malik and Shah 2007). In the present study, the scale was translated into Persian, and the reliability coefficient of the scale was again calculated using Cronbach’s alpha, which was equal to 0.88.

ALS was first proposed by Asher et al. in 1984 and revised subsequently. The scale consisted of 24 statements and a five-point answering scale with 8 deviant questions related to the interest of subjects; however, they were not used in the scoring of ALS. Thus, the main questions (n=16) of the scale were used. Besides, several questions on this scale were reversely scored (Asher, Hymel & Renshaw 1984). The scores ranged from 16-80. The cut-off point for the scale was obtained as 32. This scale had good reliability and validity, and its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated as 0.75 (Azadfaresani et al. 2013). In the present study, the reliability coefficient of the scale was again calculated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to be 0.78.

SCAS had 45 items. Responses are measured on a four-point Likert-type scale (never=0 to always=4). The questionnaire assessed 6 factors, including separation anxiety, social phobia, generalized anxiety, panic attacks, outdoor phobia obsessive-compulsive disorder, and the fear of physical injury. A total Mean±SD score of 50±10 has been considered as the average for anxiety. A T-score of ≥60 was indicative of sub-clinical or elevated levels of anxiety. (Spence 1998). In Iran, Mosavi et al. (2007) translated this scale into Persian and reported its reliability by the test-retest method as 0.89. The test’s reliability was again tested in this study, applying Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.87.

In coordination with the respected authorities of Imam Ali Society (AS), the children were interviewed and assessed by the CAS to ensure the occurrence of sexual abuse before conducting therapeutic sessions. Finally, the social work reports were investigated to select the children. For ethical considerations, informed contest forms were provided by the organization administration and children. Before starting the treatment, the ALS and SCAS were completed by the children to determine baseline conditions. Then, all children were treated for ten 45-minute sessions over 3 months at a special school, called Home Science in Malekabad-Karaj using a therapeutic package; it was compiled for this purpose based on previous scientific sources and papers, after confirming by two psychology professors and supervisors. Table 1 summarizes the treatment sessions. The content of sessions was drawn from special related sources (Blom 2006; Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Mokhtari & Rasstak 2018; Denton 2014). To assess the impact of the intervention, the authors evaluated the study participants in 4 stages. In the fourth, seventh, and tenth sessions, for follow-up, the mentioned questionnaires were again completed one month after the end of the sessions. In total, the duration of treatment and follow-up was two months.

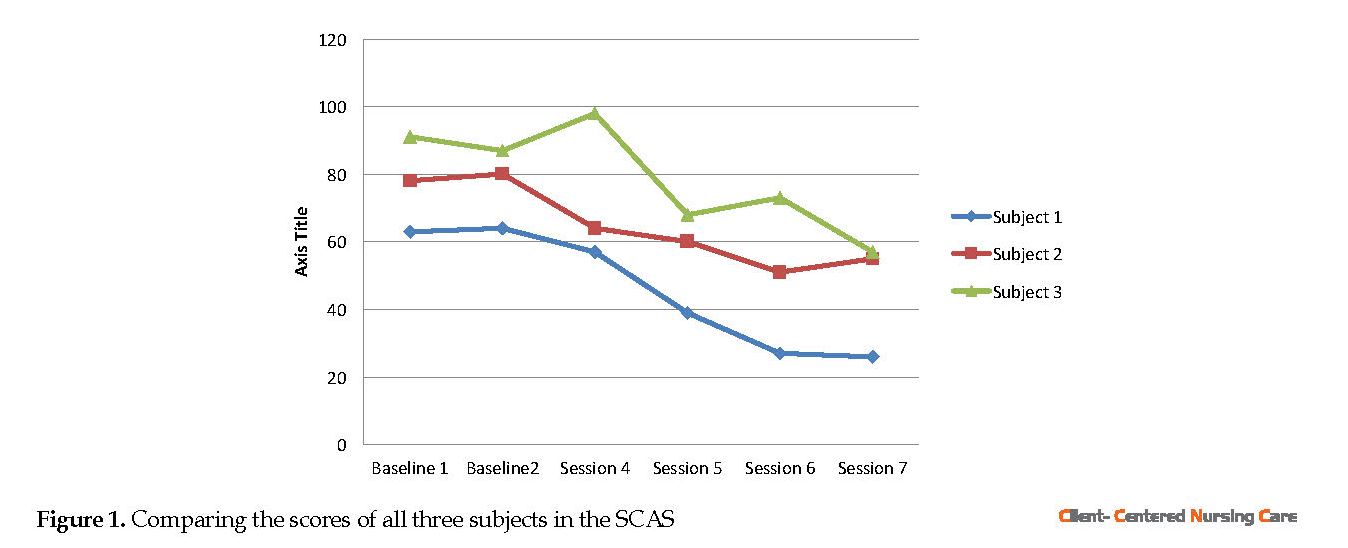

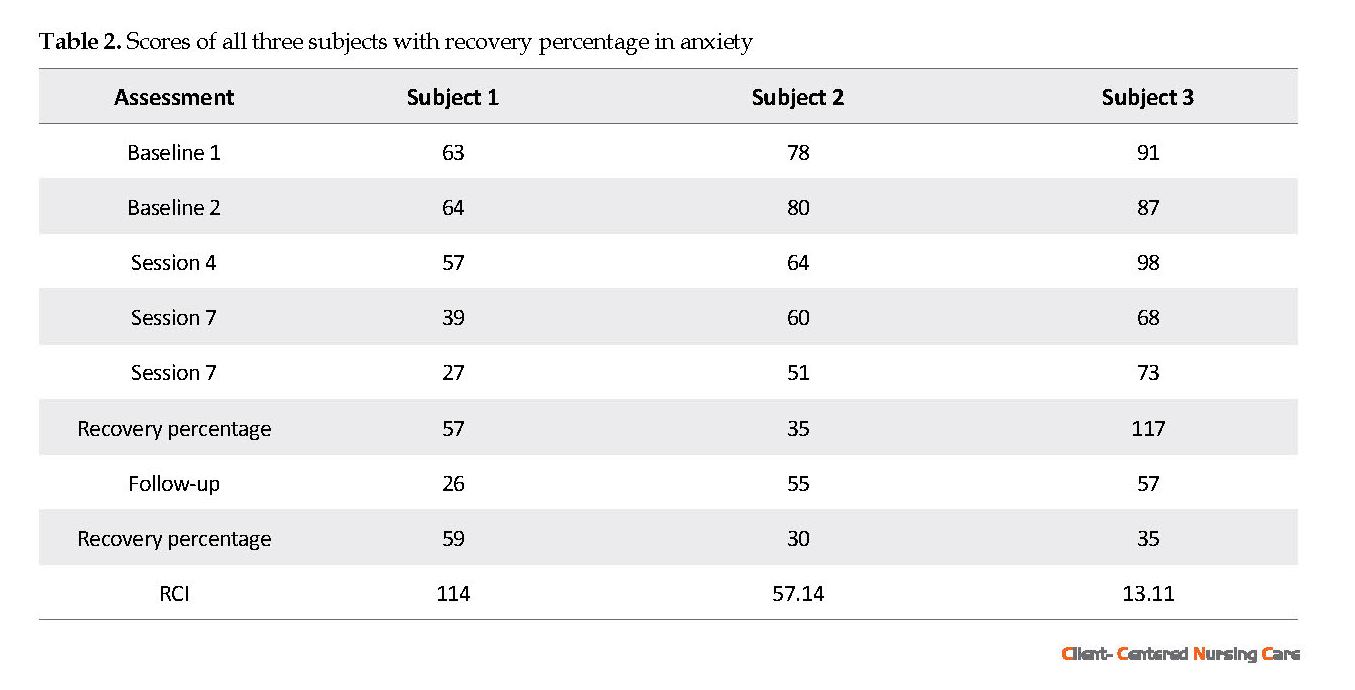

The data related to the three stages of research (baseline, treatment, and follow-up) are presented in Tables 2 and 3, as well as Figures 1 and 2. Graphical analysis was used to analyze the collected data, recovery percentage was applied to evaluate the significance, and Reliable Change Index (RCI) was used for clinical significance. RCI is calculated by dividing the difference between the pre-treatment and post-treatment scores by the double square of measured standard error (Ahmadi-Bouzedan, khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Falsafinejad 2019).

For the RCI to be statistically significant, the absolute value of the result must be ≥1.96, indicating that the results are mostly affected by active factors and the researcher’s manipulation. To calculate the recovery percentage, the pretest score is subtracted from the posttest score, and the result is divided by the pretest score. If the recovery rate is at ≥50, the results are clinically significant (Rezaee-Khoshkzari & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee 2018).

3. Results

Child 1 was an 8-year-old girl who lost her father and her two sisters. She lived with her mother and worked. She was sexually abused by street teens for being lonely and abandoned in the streets and was asked to get naked. According to the social worker, this child demonstrated high aggressiveness, and sometimes, due to high anxiety, she permanently bit her nails and corner of her scarf. Compared to her classmates, she had a relatively higher loneliness value.

Childhood is a crucial period and significantly affects human life. The presence of social harm and problems in every society puts children at greater risk than others and endangers their psychosocial health (Khairi-hassan, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Taghvaee 2016).

According to the international labor convention, child labor includes all children aged <18 years working in hazardous jobs or activities. Children's work is not defined by the activity, but as its effect on the child. The work or activity that the child does should not interfere with his/her education or pose any threat to his/her health (United Nations, 2019). According to United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) statistics, 218 million 5-17-year-old children are working, of whom 125 million are victims of hardship, and more than half (73 million children) are working in onerous physical conditions. Based on more accurate statistics, nearly half (72.1 million) of these children are living in Africa, 62.1 million in Asia and Oceania, 10.7 million in North and South America, 1.2 million in the United Arab Emirates, and 5.5 million children are working in Europe and Central Asia (Khakshour et al. 2015).

The majority of the labor force in Iran are Afghan children. Iran has 979/400 Afghan and Iraqi refugees. Iran ranks fourth in terms of accepting immigrants from war-torn countries (Refugees UNHCo, 2016). Forced migration means living in an environment where individuals continue to live with the problems. Meanwhile, their children also work, which is inappropriate for their age and adds to the problems of the host community (khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Falsafinejad & Gholeinejad 2019).

In Iran, according to unofficial statistics, about 35000 children are working in Tehran Province, Iran (Khairi-hassan, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Taghvaee 2016). The problems of labor children, in addition to human, moral, and socioeconomic dimensions, have another important aspect from the viewpoint of those who look at social issues from a health perspective (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Ashrafi & Hemmatimanesh 2013; Maccmillan et al. 2013).

The health problems of these children have affected their psychosocial health status, i.e. significantly worse than that of their peers in the relative terms (Beazzley 2015; Libório & Ungar 2010). Furthermore, the mental health of these children (in the early years of childhood) is severely damaged and leads them to low self-esteem and anxiety.

Many of these children are victims of sexual violence and are even sold as sexual slaves in exchange for money (Beazley et al. 2015; Choi, Yeoh & Lam 2019). Many governmental and nongovernmental organizations consider counseling, supportive, educational, and therapeutic services to address the biopsychosocial problems of these children (Khairi-hassan, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Taghvaee 2016; Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, et al. 2016). Children communicate very well through art therapy, play therapy, and theater-based interventions (Blom 2006).

Play therapy is a structured therapy designed based on different theories and treatments appropriate to the learning process of children and their healthy relationship with other children (Landreth 2012). Play therapy is widely used for children and adolescents who are victims of violence and sexual abuse. For example, Harvey et al. in their meta-analysis study, have revealed that play therapy is an effective measure to reduce the problems of children and multiple psychological symptoms (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Mokhtari & Rasstak 2018).

Gestalt play therapy comprises exercises involving all 5 senses of children to express emotions properly. It is a humanist and process-oriented form of therapy (Blom 2006). Violet Oaklander is considered to be the founder of Gestalt play therapy. Oaklander (1997) describes Gestalt therapy by considering that several theoretical principles of gestalt therapy, such as relationship, organismic self-regulation, contact boundary disturbances, awareness, and experience and resistance affect therapeutic work with children (Oaklander 1997; Blom 2006).

Given the verbal, cognitive, and social capacities of children, Gestalt play therapy is an appropriate intervention for them. In addition, considering the specific features of Gestalt play therapy, such as trying to inform the children of their inner and outer moods, having proper physical feedback, as well as expressing their emotions, it is expected that Gestalt play therapy desirably improve the loneliness and anxiety of these children (Harvey & Tylor 2010; Denton 2014). This theory tries to enable children to be fully present in a certain position using their senses, such as sight, hearing, and smell, which mediate between them and their environment; identifying what is being done and knowing how to perform it is the same process of maintaining contact with the environment. In this theory, some games are played with children to become aware of their senses and express their emotions, leading to the integration of personality, choice, and change (Landreth 2012; Constantinou 2007).

Additionally, emotions, such as guilt and shame in children and adolescents who were the victims of violence and sexual abuse, could be treated through Gestalt play therapy. These feelings create anger, loneliness, despair, and misery in them (Denton 2014). Besides, Gestalt play therapy could effectively decrease anxiety in children hospitalized with cancer (Constantinou 2007). In this regard, some researchers have used Gestalt play therapy to promote social adjustment and self-esteem in students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). They have concluded that this type of play therapy helps children to gain a better knowledge of themselves and to have a mutual understanding of others’ emotions (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Mokhtari & Rasstak 2018). Accordingly, the current study investigated the effect of Gestalt play therapy on anxiety and loneliness among Afghan female labor children with a sexual abuse history.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study was carried out using a Single Case Research Design (SCRD) of the AB model with two time periods. Period A was a baseline in which the study subjects’ behaviors were precisely defined; then, they were observed under normal conditions for some time. Period B was an experimental phase in which the independent variable was manipulated or entered to determine its effect on the behaviors. Finally, the subjects’ scores in each period were plotted and compared. After one month, the dependent variable was again evaluated, i.e. called the follow-up phase (Rezaee-Khoshkzari & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee 2018).

The study population consisted of all sexually-abused Afghan children aged 8-11 years in Karaj City, Iran, in 2018. Three 8-11-year-old female labor children with sexual abuse histories supported by Imam Ali Society (AS) were selected using a random sampling method. Data were collected using the Child Abuse Scale (CAS), Asher Loneliness Scale (ALS), and Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS).

CAS was designed by Malik and Shah (2007) to assess the types and severity of child abuse. It consists of 34 items covering three types of abuse: a. Physical abuse with 4 items; b. Emotional abuse with 14 items; c. Emotional abuse with 12 items; and d. Physical neglect with 4 items. These statements were written in the form of scale along with a 4-point rating scale with the categories of “never”, “seldom”, “often”, and “always”. Scale’s’ total scores ranged from 1 to 4. The scoring range for CAS was 34-136. Cut-off scores for the scale were determined by analyzing the study subjects, and the criterion was one standard deviation plus and one standard deviation below the mean scores of the study subjects. A score <54 was determined as an indicator of mild abuse; 55-65 as moderate abuse and a score of ≥66 determined severe abuse. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was also computed, and it proved to be a highly internally consistent and reliable measure of child abuse (r=0.92) (Malik and Shah 2007). In the present study, the scale was translated into Persian, and the reliability coefficient of the scale was again calculated using Cronbach’s alpha, which was equal to 0.88.

ALS was first proposed by Asher et al. in 1984 and revised subsequently. The scale consisted of 24 statements and a five-point answering scale with 8 deviant questions related to the interest of subjects; however, they were not used in the scoring of ALS. Thus, the main questions (n=16) of the scale were used. Besides, several questions on this scale were reversely scored (Asher, Hymel & Renshaw 1984). The scores ranged from 16-80. The cut-off point for the scale was obtained as 32. This scale had good reliability and validity, and its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated as 0.75 (Azadfaresani et al. 2013). In the present study, the reliability coefficient of the scale was again calculated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to be 0.78.

SCAS had 45 items. Responses are measured on a four-point Likert-type scale (never=0 to always=4). The questionnaire assessed 6 factors, including separation anxiety, social phobia, generalized anxiety, panic attacks, outdoor phobia obsessive-compulsive disorder, and the fear of physical injury. A total Mean±SD score of 50±10 has been considered as the average for anxiety. A T-score of ≥60 was indicative of sub-clinical or elevated levels of anxiety. (Spence 1998). In Iran, Mosavi et al. (2007) translated this scale into Persian and reported its reliability by the test-retest method as 0.89. The test’s reliability was again tested in this study, applying Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.87.

In coordination with the respected authorities of Imam Ali Society (AS), the children were interviewed and assessed by the CAS to ensure the occurrence of sexual abuse before conducting therapeutic sessions. Finally, the social work reports were investigated to select the children. For ethical considerations, informed contest forms were provided by the organization administration and children. Before starting the treatment, the ALS and SCAS were completed by the children to determine baseline conditions. Then, all children were treated for ten 45-minute sessions over 3 months at a special school, called Home Science in Malekabad-Karaj using a therapeutic package; it was compiled for this purpose based on previous scientific sources and papers, after confirming by two psychology professors and supervisors. Table 1 summarizes the treatment sessions. The content of sessions was drawn from special related sources (Blom 2006; Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Mokhtari & Rasstak 2018; Denton 2014). To assess the impact of the intervention, the authors evaluated the study participants in 4 stages. In the fourth, seventh, and tenth sessions, for follow-up, the mentioned questionnaires were again completed one month after the end of the sessions. In total, the duration of treatment and follow-up was two months.

The data related to the three stages of research (baseline, treatment, and follow-up) are presented in Tables 2 and 3, as well as Figures 1 and 2. Graphical analysis was used to analyze the collected data, recovery percentage was applied to evaluate the significance, and Reliable Change Index (RCI) was used for clinical significance. RCI is calculated by dividing the difference between the pre-treatment and post-treatment scores by the double square of measured standard error (Ahmadi-Bouzedan, khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Falsafinejad 2019).

For the RCI to be statistically significant, the absolute value of the result must be ≥1.96, indicating that the results are mostly affected by active factors and the researcher’s manipulation. To calculate the recovery percentage, the pretest score is subtracted from the posttest score, and the result is divided by the pretest score. If the recovery rate is at ≥50, the results are clinically significant (Rezaee-Khoshkzari & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee 2018).

3. Results

Child 1 was an 8-year-old girl who lost her father and her two sisters. She lived with her mother and worked. She was sexually abused by street teens for being lonely and abandoned in the streets and was asked to get naked. According to the social worker, this child demonstrated high aggressiveness, and sometimes, due to high anxiety, she permanently bit her nails and corner of her scarf. Compared to her classmates, she had a relatively higher loneliness value.

Child 2 was a 10-year-old girl whose parents were alive. His father was dependent on methamphetamine, and her mother stopped abusing substances. She was the third child of the family with two sisters and two brothers and was working as a peddler. One midnight, she was attacked and sexually abused by his father, who was not in a normal state because of mental imbalance related caused by methamphetamine abuse. The older boys have always touched her body or her sexual organs, but her complaint was not being taken into consideration by the family. She was afraid of dark places and loneliness. Her anxiety got much worse as the older boys approached her. Most of the time, she remained silent.

Child 3 was an 11-year-old girl, as a second child of the family with two sisters. Her father was very old, and his job was to collect wastes from garbage or people’s homes, and she worked as a peddler. Unfortunately, commuting to the family was not under control, and older men and boys came to their home. Age-inappropriate sexual images were shown to her, and sexual words were used by her and her family. The girl was first sexually abused by a teenager who touched her while wearing clothes. Then, she was abused by other men and boys. According to the social worker and objective observations, the girl had a high level of aggression and was very abusive. Additionally, she sometimes indicated signs of high anxiety and loneliness in the classroom.

In the present study, the data obtained from three stages of research (baseline, treatment, and follow-up) are presented in Tables 2 and 3, as well as Figures 1 and 2. Tables 2 illustrates the effectiveness of Gestalt play therapy on reducing anxiety in sexually-abused labor children.

In the present study, the data obtained from three stages of research (baseline, treatment, and follow-up) are presented in Tables 2 and 3, as well as Figures 1 and 2. Tables 2 illustrates the effectiveness of Gestalt play therapy on reducing anxiety in sexually-abused labor children.

Tables 2 and Figures 1 represent the changing process of the scores of the study participants 1, 2, and 3 in the SCAS inventories at baseline, intervention, and follow-up stages. According to Figures 1 and Tables 2, the anxiety rate in all studied subjects was lower than the baseline. Furthermore, the RCI for all three subjects was >1.96, representing that the results were mostly affected by active factors and the researcher’s manipulation.

Recovery percentage after the last treatment session for the subjects 1, 2, and 3 were 0.57, 0.35, and 0.17, and it was 0.59, 0.30, and 0.35 after follow-up, respectively. This demonstrated that the recovery rate was greater for subject 1 than two other study participants and was less for subject 3, compared to the two other study participants. Table 3 displays the effectiveness of Gestalt play therapy on decreasing the loneliness of sexually-abused labor children.

Table 3 and Figure 2 indicate the changing process of the scores of the study participants 1, 2, and 3 in the ALS at baseline, intervention, and follow-up stages. According to Figure 2 and Table 3, the loneliness rate was decreased in all three subjects, compared to the baseline, and the RCI for all three subjects was >1.96, demonstrating that the obtained results were mostly affected by active factors and researcher’s manipulation.

Recovery percentage after the last treatment session for the subjects 1, 2, and 3 were 0.57, 0.35, and 0.17, and it was 0.59, 0.30, and 0.35 after follow-up, respectively. This demonstrated that the recovery rate was greater for subject 1 than two other study participants and was less for subject 3, compared to the two other study participants. Table 3 displays the effectiveness of Gestalt play therapy on decreasing the loneliness of sexually-abused labor children.

Table 3 and Figure 2 indicate the changing process of the scores of the study participants 1, 2, and 3 in the ALS at baseline, intervention, and follow-up stages. According to Figure 2 and Table 3, the loneliness rate was decreased in all three subjects, compared to the baseline, and the RCI for all three subjects was >1.96, demonstrating that the obtained results were mostly affected by active factors and researcher’s manipulation.

Recovery percentage for participants 1, 2, and 3 was 0.55, 0.32, and 0.60 after last treatment session, and was 0.53, 0.50, and 0.64 after follow-up, respectively; indicating that the recovery rate was greater for participant 3, compared to the other two participants and was less for the subject 2, compared to the others.

4. Discussion

Based on the current study findings, the Gestalt play therapy reduced the anxiety of sexually-abused labor children. Constantinou et al. assessed the effectiveness of Gestalt play therapy on the anxiety of hospitalized children and concluded that it reduced their anxiety (Constantinou 2007). Moreover, Gestalt play therapy was effective on the self-esteem and adjustment of children with ADHD (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Mokhtari & Rasstak 2018). Furthermore, Gestalt play therapy was also effective in reducing the loneliness of these children. Kim also stated that child-centered play therapy could be effective in decreasing the symptoms of ADHD (Kim 2017).

Besides, another study revealed that group-based storytelling decreased anxiety and loneliness in Afghan immigrant labor children (khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Falsafinejad 2019).

It was found that group-based sand play affected diminishing the anxiety and loneliness of immigrant girls in South Korea (Jang & Kim 2012). The purpose of Gestalt play therapy is to integrate all dimensions of the child itself where the child’s senses, body, emotions, and mind work in harmony and creative adjustment (Blom 2006).

In the method used in the present study, all games were group-based, and during the sessions, the children played collaboratively together and talked about their feelings and emotions; this process resulted in the increased feelings of participation, empathy, responsibility, and acceptance of all aspects of themselves and decreased feeling of loneliness. Sexual abuse of labor children can cause problems which effects could continue throughout one’s life. Using Gestalt play therapy can effectively reduce the feelings of loneliness and anxiety in these children.

This study was limited to Afghan immigrant girls who referred to Imam Ali’s population in Karaj. Future researchers could investigate group formats, like Gestalt play therapy using a larger sample size to inform school counselors and psychologists. Treatment designs that use a randomized control trial could help treatment providers to understand the impact and usefulness of group play therapy better.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Permission was obtained by the administration of the Imam Ali Association and the children themselves. The required ethical code (96/s/423/382) was obtained from Khatam University.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, Writing review, editing, funding acquisition, and methodology: Anahita khodabakhshi-koolaee; Resources, investigation, writing original draft and supervision: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Khatam University and the personnel of Imam Ali’s Association in Karaj and the participants of the study.

References

Ahmadi Bouzendan, S., khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A. & Falsafinejad, M. R., 2019. [The effect of child centered play therapy based on nature on attention and aggression of children with asperger disorder: A single case study (Persian)]. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 5(3), pp. 59-67.

Asher, S. R., Hymel, S. & Renshaw, P. D., 1984. Loneliness in children. Child development, 55(4), pp. 1456-64. [DOI:10.2307/1130015]

Azadfaresani, Y., et al. 2013. [Psychometric features of the child’s loneliness scale in middle school students (Persian)]. Knowledge & Research in Applied Psychology, 14(1), pp. 34-42.

Beazley, H., 2015. Multiple identities, multiple realities: Children who migrate independently for work in Southeast Asia. Children’s Geographies, 13(3), pp. 296-309. [DOI:10.1080/14733285.2015.972620]

Blom, R., 2006. The handbook of gestalt play therapy: Practical guidelines for child therapists. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Choi, S. Y., Yeoh, B. S. & Lam, T., 2019. Editorial introduction: Situated agency in the context of research on children, migration, and family in Asia. Population, Space and Place, 25(3), p. e2149. [DOI:10.1002/psp.2149]

Constantinou, M., 2007. The effect of gestalt play therapy on feelings of anxiety experienced by the hospitalized oncology child [PhD. dissertation]. Pretoria: University of South Africa.

Denton, R. A., 2014. Utilizing forgiveness to help sexually abused adolescents break free from guilt and shame: A pastoral Gestalt theory. Acta Theologica, 34(2), pp. 5-28. [DOI:10.4314/actat.v34i2.1]

Harvey, S. T. & Taylor, J. E., 2010. A meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapy with sexually abused children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(5), pp. 517-35. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.006] [PMID]

Jang, M. & Kim, Y. H., 2012. The effect of group sand play therapy on the social anxiety, loneliness and self-expression of migrant women in international marriages in South Korea. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(1), pp. 38-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.aip.2011.11.008]

Khakshour, A., et al. 2015. Child labor facts in the worldwide: A review article. International Journal of Pediatrics, 3(1, 2), pp. 467-73. [DOI:10.22038/IJP.2015.3946]

Khariri-Hassan, M., Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Taghvaee, D., 2016. Comparison between aggression and anxiety among child labor with and without sexual child abuse. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 3(2), pp. 10-15. [DOI:10.21859/jpen-03022]

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A,. et al. 2016. Impact of painting therapy on aggression and anxiety of children with cancer. Caspian Journal of Pediatric, 2(2), pp. 135-41.

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Ashrafi, F. & Hemmatimanesh, A., 2013. [Aggressiveness among Afghan refugees in Iran (Persian)]. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 13 (suppl 1), p. 53.

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Falsafinejad, M. R. & Abbas Gholeinejad, M., 2019. [The effectiveness of storytelling on reducing the aggression and loneliness of Afghan refugee children (Persian)]. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 5(2), pp. 59-67.

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Mokhtari, A. R. & Rasstak, H., 2018. [The effectiveness of Gestalt play therapy on self-esteem and social adjustment in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Persian)]. Nursing Journal of Vulnerable, 5(14), pp. 1-13.

Kim, S. Y., 2017. A case study on child-centered play therapy for a child with ADHD and ODD: Focusing on the change of play theme at stage. Korean Journal of Child Studies, 38(4), pp. 103-15. [DOI:10.5723/kjcs.2017.38.4.103]

Landreth, G. L., 2012. Play therapy: The art of the relationship. Abingdon: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9780203835159]

Libório, R. M. C. & Ungar, M., 2010. Children’s labour as a risky pathways to resilience: Children’s growth in contexts of poor resources. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 23(2), pp. 232-42. [DOI:10.1590/S0102-79722010000200005]

MacMillan, H. L., et al. 2013. Child physical and sexual abuse in a community sample of young adults: Results from the Ontario child health study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), pp. 14-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.06.005] [PMID]

Malik, F. D., & Shah, A. A., 2007. Development of child abuse scale: Reliability and validity analyses. Psychology and Developing Societies, 19(2), pp. 161-78. [DOI:10.1177/097133360701900202]

Mousavi, R., et al. 2007. Psychometric properties of the Spence children’s anxiety scale with an Iranian sample. International Journal of Psychology, 1(1), pp. 1-9.

Oaklander, V., 1997. The therapeutic process with children and adolescents. Gestalt Review, 1(4), pp. 292-317.

Rezaee Khoshkozari, G. & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., 2018. [The effectiveness of floor time play on anxiety in children with Asperger disorder and burden among their mothers: A single case study (Persian)]. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 4(4), pp. 50-9.

Spence, S. H., 1998. A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(5), pp. 545-66. [DOI:10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00034-5]

United Nation., 2019. World day against child labour. Geneva: United Nation.

United Nations Human Rights office of the High Commissioner., 2016. Convention relating to the Status of Refugees [Internet]. Cited 12 September 2016, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/statusofrefugees.aspx

Based on the current study findings, the Gestalt play therapy reduced the anxiety of sexually-abused labor children. Constantinou et al. assessed the effectiveness of Gestalt play therapy on the anxiety of hospitalized children and concluded that it reduced their anxiety (Constantinou 2007). Moreover, Gestalt play therapy was effective on the self-esteem and adjustment of children with ADHD (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, Mokhtari & Rasstak 2018). Furthermore, Gestalt play therapy was also effective in reducing the loneliness of these children. Kim also stated that child-centered play therapy could be effective in decreasing the symptoms of ADHD (Kim 2017).

Besides, another study revealed that group-based storytelling decreased anxiety and loneliness in Afghan immigrant labor children (khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Falsafinejad 2019).

It was found that group-based sand play affected diminishing the anxiety and loneliness of immigrant girls in South Korea (Jang & Kim 2012). The purpose of Gestalt play therapy is to integrate all dimensions of the child itself where the child’s senses, body, emotions, and mind work in harmony and creative adjustment (Blom 2006).

In the method used in the present study, all games were group-based, and during the sessions, the children played collaboratively together and talked about their feelings and emotions; this process resulted in the increased feelings of participation, empathy, responsibility, and acceptance of all aspects of themselves and decreased feeling of loneliness. Sexual abuse of labor children can cause problems which effects could continue throughout one’s life. Using Gestalt play therapy can effectively reduce the feelings of loneliness and anxiety in these children.

This study was limited to Afghan immigrant girls who referred to Imam Ali’s population in Karaj. Future researchers could investigate group formats, like Gestalt play therapy using a larger sample size to inform school counselors and psychologists. Treatment designs that use a randomized control trial could help treatment providers to understand the impact and usefulness of group play therapy better.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Permission was obtained by the administration of the Imam Ali Association and the children themselves. The required ethical code (96/s/423/382) was obtained from Khatam University.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, Writing review, editing, funding acquisition, and methodology: Anahita khodabakhshi-koolaee; Resources, investigation, writing original draft and supervision: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Khatam University and the personnel of Imam Ali’s Association in Karaj and the participants of the study.

References

Ahmadi Bouzendan, S., khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A. & Falsafinejad, M. R., 2019. [The effect of child centered play therapy based on nature on attention and aggression of children with asperger disorder: A single case study (Persian)]. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 5(3), pp. 59-67.

Asher, S. R., Hymel, S. & Renshaw, P. D., 1984. Loneliness in children. Child development, 55(4), pp. 1456-64. [DOI:10.2307/1130015]

Azadfaresani, Y., et al. 2013. [Psychometric features of the child’s loneliness scale in middle school students (Persian)]. Knowledge & Research in Applied Psychology, 14(1), pp. 34-42.

Beazley, H., 2015. Multiple identities, multiple realities: Children who migrate independently for work in Southeast Asia. Children’s Geographies, 13(3), pp. 296-309. [DOI:10.1080/14733285.2015.972620]

Blom, R., 2006. The handbook of gestalt play therapy: Practical guidelines for child therapists. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Choi, S. Y., Yeoh, B. S. & Lam, T., 2019. Editorial introduction: Situated agency in the context of research on children, migration, and family in Asia. Population, Space and Place, 25(3), p. e2149. [DOI:10.1002/psp.2149]

Constantinou, M., 2007. The effect of gestalt play therapy on feelings of anxiety experienced by the hospitalized oncology child [PhD. dissertation]. Pretoria: University of South Africa.

Denton, R. A., 2014. Utilizing forgiveness to help sexually abused adolescents break free from guilt and shame: A pastoral Gestalt theory. Acta Theologica, 34(2), pp. 5-28. [DOI:10.4314/actat.v34i2.1]

Harvey, S. T. & Taylor, J. E., 2010. A meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapy with sexually abused children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(5), pp. 517-35. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.006] [PMID]

Jang, M. & Kim, Y. H., 2012. The effect of group sand play therapy on the social anxiety, loneliness and self-expression of migrant women in international marriages in South Korea. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(1), pp. 38-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.aip.2011.11.008]

Khakshour, A., et al. 2015. Child labor facts in the worldwide: A review article. International Journal of Pediatrics, 3(1, 2), pp. 467-73. [DOI:10.22038/IJP.2015.3946]

Khariri-Hassan, M., Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Taghvaee, D., 2016. Comparison between aggression and anxiety among child labor with and without sexual child abuse. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 3(2), pp. 10-15. [DOI:10.21859/jpen-03022]

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A,. et al. 2016. Impact of painting therapy on aggression and anxiety of children with cancer. Caspian Journal of Pediatric, 2(2), pp. 135-41.

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Ashrafi, F. & Hemmatimanesh, A., 2013. [Aggressiveness among Afghan refugees in Iran (Persian)]. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 13 (suppl 1), p. 53.

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Falsafinejad, M. R. & Abbas Gholeinejad, M., 2019. [The effectiveness of storytelling on reducing the aggression and loneliness of Afghan refugee children (Persian)]. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 5(2), pp. 59-67.

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Mokhtari, A. R. & Rasstak, H., 2018. [The effectiveness of Gestalt play therapy on self-esteem and social adjustment in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Persian)]. Nursing Journal of Vulnerable, 5(14), pp. 1-13.

Kim, S. Y., 2017. A case study on child-centered play therapy for a child with ADHD and ODD: Focusing on the change of play theme at stage. Korean Journal of Child Studies, 38(4), pp. 103-15. [DOI:10.5723/kjcs.2017.38.4.103]

Landreth, G. L., 2012. Play therapy: The art of the relationship. Abingdon: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9780203835159]

Libório, R. M. C. & Ungar, M., 2010. Children’s labour as a risky pathways to resilience: Children’s growth in contexts of poor resources. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 23(2), pp. 232-42. [DOI:10.1590/S0102-79722010000200005]

MacMillan, H. L., et al. 2013. Child physical and sexual abuse in a community sample of young adults: Results from the Ontario child health study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), pp. 14-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.06.005] [PMID]

Malik, F. D., & Shah, A. A., 2007. Development of child abuse scale: Reliability and validity analyses. Psychology and Developing Societies, 19(2), pp. 161-78. [DOI:10.1177/097133360701900202]

Mousavi, R., et al. 2007. Psychometric properties of the Spence children’s anxiety scale with an Iranian sample. International Journal of Psychology, 1(1), pp. 1-9.

Oaklander, V., 1997. The therapeutic process with children and adolescents. Gestalt Review, 1(4), pp. 292-317.

Rezaee Khoshkozari, G. & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., 2018. [The effectiveness of floor time play on anxiety in children with Asperger disorder and burden among their mothers: A single case study (Persian)]. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 4(4), pp. 50-9.

Spence, S. H., 1998. A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(5), pp. 545-66. [DOI:10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00034-5]

United Nation., 2019. World day against child labour. Geneva: United Nation.

United Nations Human Rights office of the High Commissioner., 2016. Convention relating to the Status of Refugees [Internet]. Cited 12 September 2016, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/statusofrefugees.aspx

Type of Study: case report |

Subject:

General

Received: 2018/12/15 | Accepted: 2019/05/10 | Published: 2019/08/1

Received: 2018/12/15 | Accepted: 2019/05/10 | Published: 2019/08/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |