BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-260-en.html

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Khatam University, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities, Khomein Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khomein, Iran.

● The findings of this study indicated that the two models of mindfulness-based self-compassion and attachment-based therapy reduced the negative emotions and thoughts, such as self-criticism and fatigue among adolescents with addiction potential.

● There was no difference between mindfulness-based self-compassion and attachment-based therapy models in terms of their effect on self-criticism and mental fatigue of male adolescents with addiction potential.

Plain Language Summary

Addiction readiness is one of the problems, which is more likely to occur in adolescence. Some psychological traits, such as self-criticism and mental fatigue lead to negative emotions in adolescents. As a result, the adolescent may be drawn to drugs to relieve stress and negative emotions. According to the findings of this study, mindfulness-based self-compassion and attachment-based therapy as two therapeutic interventions are applicable and effective for decreasing negative emotions and raising the self-confident and assertive behaviors among adolescents with addiction potential.

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a transitional stage in physical and psychological development that occurs between childhood and adulthood. This transition includes biological changes, such as sexual, social, and psychological maturation; however, only biological and psychological changes can be easily measured (Chiristie & Viner, 2005). From the perspective of evolutionary psychology, adolescence can be considered as a period of the expression of psychological symptoms (Olumide et al. 2014). Adolescence is also one of the most important stages in human development, which is associated with many psychological and social impacts. This period represents a profound change that distinguishes children from adults (Khodabakhshi Koolaee et al. 2014).

These changes and developments create issues that are specific to adolescence. Emotions, such as self-criticism and mental fatigue are among the main concerns associated with adolescence (Ghanbari Taleb et al. 2013). Accordingly, many threats impact adolescents during this period. One of these threats is the vulnerability of adolescents to addiction (Budden 2009). Psychological and emotional factors are among the main reasons making adolescents and young people prone to drug abuse, and people who lack skills to control their emotions are more likely for addiction (Khodabakhshi Koolaee & Damirchi 2016).

Self-criticism and psychological fatigue are among the psychological factors that underlie adolescents’ tendency to addiction. A theoretical and experimental model proposed by Randles & Tracy claims that motivational, cognitive, and interpersonal characteristics of self-criticism interact dynamically with environmental factors and increase and maintain psychological trauma and discomfort including substance use (Randles & Tracy 2013; Pinto-Gouveia & Matos 2011). Self-criticism and shame play an important role in anger, social anxiety, mood disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and interpersonal problems (Gillbert & Procter 2006).

A study on the role of self-criticism as a feature of the diagnostic process for different types of adolescent psychological pathology showed that comparative self-criticism creates frustration, feelings of inferiority, and inadequate self-criticism (Irons & Lad 2017). It was also shown that internal self-criticism causes self-hate and both forms of self-criticism (internal and external) are positively correlated (Salvador et al. 2017). Although there have been some studies on fatigue behavior, it is not clearly understood.

The number of definitions proposed about the nature of fatigue is nearly the same as the number of empirical studies on the subject, much of which depends largely on the interests and intellectual backgrounds of authors of the articles. For example, psychiatric researchers typically study fatigue by examining defense mechanisms and neuroticism, while psychologists typically study fatigue through burnout caused by industrial life, monotony, and alertness, and pay less attention to theoretical aspects of personality. Hamilton emphasizes that different interpretations of fatigue are due to antecedents and conditions, psychological dependence, phenomenological requirements, and behavioral consequences (Hamilton 1981).

New approaches to the concept of fatigue are perspective dependent. Hamilton believes that the sensory habits (e.g., providing entertainment, growth of interest, and prevention of fatigue) that are needed to create a separate identity can be developed to a very small extent during the developmental stages (Hamilton 1981). Hamilton et al. maintained that how individuals learn to entertain themselves and cope with fatigue has potentially extensive adverse consequences for the individual, society, and ecology. They also suggested that individual differences in attention and other individual traits are important in regulating the chain of experiences ranging from attention to feeling tired (Hamilton et al. 1984).

It has been stated that psychological fatigue and family background are correlated. In some families, there are higher expectations of parents and children, and there are personality traits, such as conscientiousness and physical illness symptoms. Given the effect of the mentioned factors, the role of therapeutic and preventive factors in this stage of growth will be more prominent. Preventive therapies that can be implemented at this stage include modern therapies, such as mindfulness-based compassion therapy, which specifically focuses on the here and now, and also purposeful and judgment-free ways (Ozturk et al. 2019). T

he simplest definition derived from the teachings of the Buddha is that “compassion” is the sensitivity to suffering in ourselves and others, along with the motivation and commitment to reduce and eliminate it. In other words, the goal of self-healing treatment based on mindfulness is to pay attention to a specific way, focusing on the goal in the present without judgment. In mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy, people learn not to avoid their painful feelings and not to suppress them. Therefore, they can know their experience in the first step and feel compassion for it (Rase 2011).

Self-compassion exercises focus on relaxation, meditation, self-kindness, and mindfulness, which play an important role in calming one’s mind and reducing stress and negative automatic thoughts (Gillbert & Procter, 2006; Kelly 2009). Some studies have emphasized the role of compassion-focused therapy in reducing shame and self-criticism in people with trauma (Rase 2011), decreasing self-esteem and negative thoughts (Shaver & Mikulincer 2005), self-criticism, and feelings of shame and failure (Rayn & Deci 2000; Ainsworth 1989), as well as increasing feelings of warmth and acceptance. Besides, compassion-focused therapy contributes to reducing clients’ psychological problems by increasing inner awareness, non-judgmental acceptance, empathy, and constant attention to inner feelings (Passanisi et al. 2015).

Another therapeutic factor influencing the tendency of adolescents to addiction can be attributed to the attachment style of individuals. Based on the latest empirical intercultural findings concerning the importance of innate factors in personality development and behavior, there are three basic psychological needs in humans: 1) The need for competence, 2) the need for self, and 3) the need for communication and commitment (Cornell & Frick 2007). Attachment is a deep emotional bond that we establish with certain people in our lives, so that interacting with them leads to a sense of vitality and joy, and when we are stressed, we feel at ease with them. Attachment is a special emotional relationship that requires the exchange of pleasure, care, and comfort.

On the other hand, the pathological cause of self-criticism and psychological fatigue may be related to people’s attachment experiences in childhood and is originated from the experience of the first stage of life in response to rejection or separation from child caregivers (Heidelberg & Andrews 2011). Anxious and avoidant attachment styles are associated with unpleasant psychological symptoms, such as shame, anger, and narcissism (Akbag & Imanoglu 2010; Schimmenti 2012). Detached and secure attachment styles can predict self-criticism. Many negative, self-critical emotions can also be triggered by insecure attachment styles (Pace & Zappulla 2013; Lewis 2008; Whittle et al. 2016).

People with insecure attachment styles are indirectly vulnerable to addiction through sensation-seeking mediation. The indirect paths of attachment and moral intelligence are significantly associated with the tendency to addiction through sensation seeking (Muris & Meesters 2013). Variables, such as family communication patterns and attachment styles are related to substance abuse tendencies. Based on what has been mentioned and according to attribution theory (Boersma et al. 2015) about self-criticism, these feelings can vary from one society to another, one group to another, and one person to another.

Besides, according to the results of previous studies (Boersma et al. 2015; Bluth & Gaylord 2015), the experience of self-criticism and mental fatigue during adolescence is more frequent due to the special characteristics of adolescents, and the students who experience negative emotions, such as self-criticism, face motivational barriers and delay most academic activities because they fear the consequences of failure at school, which can be accompanied by feelings of self-criticism and fatigue. The mindfulness-based self-compassion model helps a person to adopt a compromising approach and take a closer look at what is going on in their life.

Furthermore, attachment-based therapy also helps the individual to have a secure attachment with a new self-awareness, and ultimately both models help to reduce disturbing emotions, such as self-criticism and mental fatigue. Accordingly, the present study seeks to compare the effectiveness of two models of mindfulness-based self-compassion and attachment-based therapy on self-criticism and mental fatigue of male adolescents with the addiction potential.

2.Materials and Methods

Design and sample

The present study employed a quasi-experimental method with a pre- and post-test design. The mindfulness-based self-compassion and attachment-based therapies were taken as independent variables, and self-criticism and mental fatigue were manipulated as dependent variables. The research population included all high school students who were studying in the academic year 2018-2019 in Azna County, Lorestan Province. The subjects were selected through cluster sampling. To this end, all high schools in the studied region were selected as clusters, and among the selected schools, 7 classes with 140 students in total were randomly selected and the Addiction Potential Scale (APS) was administered to the students. Finally, among the students with a score above 60 on the APS, 45 students were selected and randomly assigned to two experimental groups and one control group, each with 15 students. The inclusion criteria were obtaining a score of 60 on APS and not participating in other treatment courses. The exclusion criteria were having a physical or psychological illness as diagnosed by a physician, being a single-parent student, and being absent for more than three sessions of treatment.

Instruments

A. Addiction Potential Scale (APS)

The scale was developed by Weed et al (1992). The Persian version of the scale was developed by Zargar et al. (2008) based on the psychosocial characteristics of Iranian society. It contains 36 items plus 5 lie detector items. They used two methods to assess the validity of this scale. Testing the criterion validity showed that this scale can properly differentiate between addicts and non-addicts. Besides, a significant correlation (r=0.45) was found between this scale and the SCL-25

(Symptom Checklist) that supported the construct validity of the APS. The reliability of the scale was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha method and the reliability index was 0.90, which was within the optimal limit. Each item is scored on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (totally disagree) to 3 (totally agree).

This scale has a lie detector factor measured through items 12, 15, 21, and 33, and these items are scored reversely. To calculate the overall score of the scale, the total scores of each item (except the lie detector items) are calculated. This score ranges from 0 to 108. The cut-off point on the scale is 54. Higher scores indicate that the respondent is more prone to addiction, and vice versa (Zargar et al. 2008). In this study, the students with a score greater than 60 were selected and assigned to the experimental and control groups. The validity and reliability of this scale were also calculated and confirmed.

B. The Levels of Self-criticism (LOSC) Scale

The scale was developed by Lewis (2008). This scale measures self-criticism at two levels: Internalized self-criticism and comparative self-criticism. Comparative self-criticism is defined as a negative view of oneself against others. Self-critical people often tend to base their self-esteem on perceptions of the way others feel about them and may view other individuals as superior, critical, and/or hostile. Thus, one of the characteristics of self-criticism is the comparison of interpersonal animosity (Thompson & Zuroff 2004). Internalized self-criticism is defined as a negative view of oneself against one’s internal standards. The LOSC Scale contains 22 items that are scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 to 6. Items 6, 8, 11, 12, 16, 20, and 21 are scored reversely. The items on the internalized self-criticism subscale include 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, and 19, and items on the comparative self-criticism subscale are 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21, and 22. The items on the LOSC scale are measured on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Higher scores on this scale indicate a higher level of self-criticism experienced by an individual. A score between 22 and 44 indicates low levels of self-criticism and a score between 45 and 66 indicates moderate levels of self-criticism in the individual. Finally, a score above 66 indicates high levels of self-criticism. Saadati Shamir et al. in Iran reported a good internal consistency for this scale (Cronbach’s alpha=0.69) (Saadati Shamir, Mazboohi, & Marzi 2018). In this study, the reliability of the Persian version of the scale was measured using Cronbach’s alpha with an internal consistency of 0.82.

C. The Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)

The psychometric properties of the scale were assessed by Krupp et al. (1989). The scale contains 9 items that were extracted from the 28-item Fatigue Severity Scale. Krupp et al. first used a 28-item fatigue severity scale to study 25 people with multiple sclerosis, 29 people with lupus, and 20 healthy people, and chose 9 items dealing with the consequences of fatigue in terms of functional and welfare aspects in the two groups of patients. The correlation value of the scores of these items in both groups of patients was higher than in healthy individuals. The Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) measures people’s fatigue using 9 items that are sensitive to energy adjustment programs and time changes. The scale items are scored using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7. The scale scores are interpreted based on the total score gained by the individual.

The minimum possible score is 9 and the maximum score is 63. A score between 9 and 18 shows low fatigue, a score between 18 and 45 indicates moderate fatigue, and a score above 45 shows a high level of fatigue. The reliability and construct validity of the scale were assessed by Krupp et al. The Cronbach’s alpha values for healthy, multiple sclerosis and lupus people were 0.88, 0.81, and 0.89, respectively, and the FSS had a high internal consistency. They concluded that the scale had good validity and reliability (Krupp et al, 1989). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the Persian version of the scale was calculated as 0.96 (Azimian et al. 2009).

D. Demographic Questionnaire

This questionnaire was developed to examine students’ demographic information, such as age, education, and parents’ occupation.

Procedure

To comply with ethical considerations, written ethical consent was obtained from the participants and their information was kept confidential. Besides, three treatment sessions were held for the participants in the control group after the completion of the study. The content of the mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy program was taken from the Rase and Neff approach (Rase 2011; Neff 2012) and the poems of Mawlana Rumi’s five books of the Masnavi, and the protocol was performed in eight sessions each lasting 90 min.

Besides, attachment-based therapy was developed in six 90-min sessions based on the materials provided by Anisworth (1989) and Milulincer et al. (2005). The content of the therapies was implemented in groups by the researcher as detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The meetings were held for two months (one session weekly) in the counseling center of education organization. Therapeutic interventions were not provided to the control group during the study. There was no attrition in the sample. The chart of the study process is shown in Diagram 1. Finally, the collected data were analyzed using a one-way and multivariate analysis of covariance by SPSS software V. 21.

3. Results

The analysis of the participants’ demographic data showed that the average age of the students in all groups was 16.82 years and there was no difference among the groups in terms of individual characteristics.

As can be seen in table 3, there is a difference between the Mean±SD of the three groups on the pre-test and post-test. To find out if these differences are significant or not, ANOVA test was run.

.jpg)

The Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances shows that the calculated F was not significant for all three variables (P>0.05); thus, the assumption of homogeneity of variances was confirmed. In addition, the calculated F value was not significant (P>0.05). Therefore, the variance homogeneity assumption was confirmed in the covariance matrix.

The main hypothesis tested in this study was that there is a significant difference between mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy in terms of their effects on self-criticism and mental fatigue of male adolescents with addiction potential.

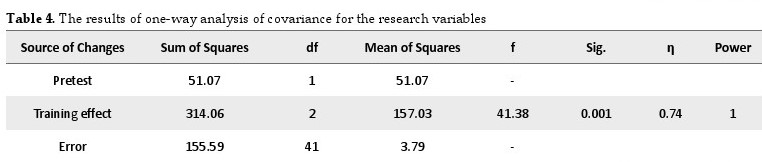

As can be seen in Table 4, there was a significant difference between mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy in terms of their effects on self-criticism and mental fatigue of male adolescents with addiction potential with the control group. The results of one-way ANCOVA suggested that the calculated F value was significant. Therefore, mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy are effective on at least one of the dependent variables.

The value of the ETA coefficient indicated that the effectiveness of the training on the dependent variables was 74%. In other words, 67% of the variance of the dependent variables was explained by mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy. The statistical power value shows that, first, the sample size was sufficient. Second, if mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy are performed on the dependent variable for multiple times, the results will be the same.

The results of multivariate ANCOVA suggested that the calculated F value was significant. Therefore, mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy are effective on at least one of the dependent variables. The value of the ETA coefficient indicated that the effectiveness of the training on the dependent variables was 58%. In other words, 58% of the variance of the dependent variables was explained by mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy (Table 5).

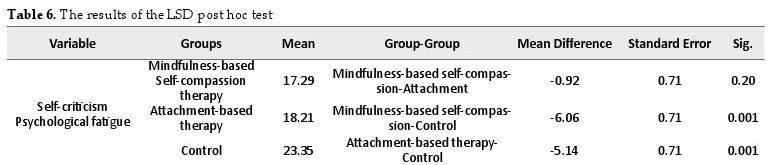

As can be seen in Table 6, there was a significant difference between mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy in terms of their effects on self-criticism and mental fatigue of male adolescents with addiction potential.

As can be seen in Table 7, the values calculated for all variables in all three groups were not significant; thus, the data distribution normality assumption was confirmed.

In Table 8, there was a significant difference between mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy in terms of their effects on self-criticism and mental fatigue of male adolescents with addiction potential.

4. Discussion

The present study compared the two models of mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy in terms of their effects on self-criticism and mental fatigue of male adolescents with addiction potential. The results showed the effectiveness of these two treatment models in preventing the tendency of adolescents to drug abuse. This finding is consistent with previous studies. For instance, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee et al. and Dunning et al. found that mindfulness-based self-compassion training leads to improvement and promotion of people’s cognitive emotion regulation. Mindfulness-based self-compassion training can accelerate a person’s ability to choose more useful and effective responses to interpersonal interactions by preventing automatic, impulsive, or thoughtless reactions (Khodabakhshi Koolaee, Chaeichi Tehrani & Sanagoo 2019; Dunning et al. 2019).

This type of deep and thoughtful process can improve communication and acceptance in relationships by preventing bold, reckless, and thoughtless communication, which is often a characteristic of intrapersonal and interpersonal conflicts (Khodabakhshi Koolaee et al. 2017). Since mindfulness exercises can not only enhance awareness of inner experience, but also improve appreciation and kindness toward that experience, adolescents become more aware of their thoughts and feelings and consider them merely as subjective events, not aspects of themselves, and as a result, the way they relate the experiences to their thoughts will be changed (Dunning et al. 2019). This change enables them to be aware of their strengths and weaknesses and their lives at all times, and ultimately, they are expected to reduce negative emotions, such as self-criticism and mental fatigue.

Attachment-based therapy also identifies communication patterns, emotions, feelings, and the exchange of attachment styles. Communicative and interactive patterns in adolescents determine levels of self-criticism and psychological fatigue in life. In other words, a destructive interactive style increases the emotional distance between oneself and others, which in turn exacerbates conflicting and negative emotions towards oneself and others. Emphasis-focused therapy concentrates on reducing self-criticism and mental fatigue by emphasizing the discovery and recognition of interactive styles and the replacement of new perceptions of communication style by controlling emotions and changing dysfunctional communication cycles.

The present study is significant because it can be effective in treating people who are self-critical and suffer from mental fatigue as the insights from the study can provide a context for people to experience secure attachment and to resolve their psychological conflicts using this attachment style. In general, the higher the level of secure attachment in childhood and adolescence, the more likely a person is to adopt a successful identity base in adolescence. Montero-Marin et al. concluded that early childhood traumas, harsh and emotionless characteristics, and insecure attachment styles are risk factors for aggression and should be addressed through psychological interventions (Montero-Marin et al 2020). Attachment styles can affect opioid use disorders through family interaction processes, social control, emotion regulation, and self-efficacy (Marshall et al. 2015).

These findings indicate the extent to which the attachment-based therapy model is effective in reducing negative emotions. Finally, two models of mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy can be effective in reducing self-criticism and mental fatigue. The results of this study showed that both approaches are promising. The results also add to the empirical knowledge related to the two treatment models that can contribute to alleviating problems caused by self-criticism and mental fatigue in male adolescents with addiction potential.

5.Conclusion

Mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy and attachment-based therapy can be effective in reducing self-criticism and mental fatigue in male adolescents prone to addiction. This study can offer practical insights by considering the role of mindfulness-based self-compassion and attachment-based therapy techniques in reducing adolescents’ problems. Therefore, it is recommended to use these treatment techniques seriously to deal with the problems experienced by adolescents in different situations, especially in schools.

To mention a limitation, this study was conducted on high school boys in Azna City, Lorestan Province. Also, due to time constraints, follow-up tests were not performed to investigate the retention effects of the interventions.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was registered at Khatam University with a code of ethics (Code: IR.KHATAMU.REC.1397.13). Written ethical consent was obtained from the participants and their parents and their information was kept confidential. Besides, three treatment sessions were held for the participants in the control group after the completion of the study.

Funding

The present paper was extracted from PhD. thesis of the first author, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities, Khomein Branch, Islamic Azad University (Code: 26221602971006).

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to appreciate the managers and staff of counseling centers of the Azna Education Department.

References

Akbag, M., & Imamoglu, S. E., 2010. the prediction of gender and attachment styles on shame, guilt, and loneliness. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 10(2), 669-82. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ889191

Ainsworth, M. S., 1989. Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709-16. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709] [PMID]

Azimian, M., et al., 2009. Fatigue severity scale: The psychometric properties of the Persian-version in patients with multiple sclerosis. Research Journal of Biological Sciences, 4(9), 974-7. https://medwelljournals.com/abstract/?doi=rjbsci.2009.974.977

Bluth, K., Roberson, P. N. E. & Gaylord, S. A., 2015. A pilot study of a mindfulness intervention for adolescents and the potential role of self-compassion in reducing stress. Explore (NY), 11(4), 292-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.explore.2015.04.005] [PMID] [PMCID]

Boersma, K., et al., 2015. Compassion focused therapy to counteract shame, self-criticism and isolation. A replicated single case experimental study for individuals with social anxiety. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 45(2), 89-98. [DOI:10.1007/s10879-014-9286-8]

Budden, A., 2009. The role of shame in posttraumatic stress disorder: A proposal for a socio-emotional model for DSM-V. Social Science & Medicine, 69(7), 1032-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.032] [PMID]

Christie, D., & Viner, R., 2005. Adolescent development. BMJ, 330(7486), 301-4. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.330.7486.301] [PMID] [PMCID]

Cornell, A. H., & Frick, P. J., 2007. The moderating effects of parenting styles in the association between behavioral inhibition and parent-reported guilt and empathy in preschool children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(3), 305-18. [DOI:10.1080/15374410701444181] [PMID]

Dunning, D. L., et al., 2019. Research Review: The effects of mindfulness‐based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents-a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(3), 244-58. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12980] [PMID] [PMCID]

Ghanbari Talab, M., et al., 2013. The relationship between emotional intelligence and addiction potential tendency pre-university students. Journal of Shahrekord University of Medical Science, 15(3), 33-9. http://journal.skums.ac.ir/article-1-1570-fa.html

Gilbert, P., & Procter, S., 2006. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self‐criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. The Journal of Analytical Psychology, 13(6), 353-79. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.507]

Hamilton, J. A., & JA, H., 1981. Attention personality and the self-regulation of mood: Absorbing interest and boredom. Pascal and Francis Bibliographic Databases, 10, 281-315. https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=PASCAL82X0041498

Hamilton, J. A., Haier, R. J., & Buchsbaum, M. S., 1984. Intrinsic enjoyment and boredom coping scales: Validation with personality, evoked potential and attention measures. Personality and Individual Differences, 5(2), 183-93. [DOI:10.1016/0191-8869(84)90050-3]

Heidelberg, J., & Andrews, B., 2011. The relationship between shame and different types of anger: A theory-based investigation. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(8), 1278-82. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.024]

Irons, C., & Lad, S., 2017. Using compassion focused therapy to work with shame and self-criticism in complex trauma. Australian Clinical Psychologist, 3(1), 1743-54. https://acp.scholasticahq.com/article/1743-using-compassion-focused-therapy-to-work-with-shame-and-self-criticism-in-complex-trauma

Kelly, A., C., Zuroff, D. C., & Shapira, L. B., 2009. Soothing oneself and resisting self-attacks: The treatment of two intrapersonal deficits in depression vulnerability. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 33(3), 301-13. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-008-9202-1]

Khodabakhshi Koolaee, A., Chaeichi Tehrani, N., & Sanagoo, A., (2019). [The relationship between spiritual intelligence and emotional intelligence with self-compassion of nursing students (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Medical Education, 19(5), 44-53. http://ijme.mui.ac.ir/article-1-4697-en.html

Khodabakhshi Koolaee, A., et al., 2017. [Comparison of self-compassion and attachment to God between prison and non-prison women: A case control study in Tehran (Persian)]. Nursing Journal of the Vulnerable, 4(11), 46-60. http://njv.bpums.ac.ir/article-۱-۷۷۹-fa.html

Khodabakhshi Koolaee, A., & Damirchi, F., 2016. Comparing quality of life among female sex workers with and without addiction. Journal of Client-Centered Nursing Care, 2(4), 201-6. [DOI:10.32598/jccnc.2.4.201]

Khodabakhshi Koolaee A., et al., 2014. Comparison between family power structure and the quality of parent-child interaction among the delinquent and non-delinquent adolescents. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors & Addiction, 3(2),e13188 [DOI:10.5812/ijhrba.13188] [PMID] [PMCID]

Krupp, L. B., et al., 1989. The fatigue severity scale: Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Archives of Neurology, 46(10), 1121-3. [DOI:10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022] [PMID]

Lewis, M., 2008. Self-conscious emotions: Embarrassment, pride, shame, and guilt. Handbook of Emotions, 742-56. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-07784-046

Marshall, S. L., et al., 2015. Self-compassion protects against the negative effects of low self-esteem: A longitudinal study in a large adolescent sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 116-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.013]

Mikulincer, M., et al., 2005. Attachment, caregiving, and altruism: boosting attachment security increases compassion and helping. Journal of personality and social psychology, 89(5), 817.

Montero-Marin, J., et al., 2020. Attachment-Based Compassion Therapy for Ameliorating Fibromyalgia: Mediating Role of Mindfulness and Self-Compassion. Mindfulness, 11(3), 816-28. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-019-01302-8]

Muris, P., & Meesters, C., 2014. Small or big in the eyes of the other: On the developmental psychopathology of self-conscious emotions as shame, guilt, and pride. Clinical child and Family Psychology Review, 17(1), 19-40. [DOI:10.1007/s10567-013-0137-z] [PMID]

Neff, K. D., 2012. The science of self-compassion. In C. Germer, & R. Siegel (Eds.), Compassion and Wisdom in Psychotherapy. (pp. 79-92). New York, NY: Guilford Press. https://www.scirp.org/(S(i43dyn45teexjx455qlt3d2q))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1999978

Olumide, A. O., et al., 2014. Predictors of substance use among vulnerable adolescents in five cities: findings from the well-being of adolescents in vulnerable environments study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(6), S39-47. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.024] [PMID] [PMCID]

Ozturk, Y., Moretti, M., & Barone, L., 2019. Addressing parental stress and adolescents’ behavioral problems through an attachment-based program: An intervention study international. Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 19(1), 89-100. https://www.ijpsy.com/volumen19/num1/509.html

Pace, U., & Zappulla, C., 2013. Detachment from parents, problem behaviors, and the moderating role of parental support among Italian adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 34(6), 768-83. [DOI:10.1177/0192513X12461908]

Passanisi, A., et al., 2015. The relationship between guilt, shame and self-efficacy beliefs in middle school students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197, 1013-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.295]

Pinto‐Gouveia, J., & Matos, M., 2011. Can shame memories become a key to identity? The centrality of shame memories predicts psychopathology. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(2), 281-90. [DOI:10.1002/acp.1689]

Raes, F., 2011. The effect of self-compassion on the development of depression symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Mindfulness, 2(1), 33-6. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-011-0040-y]

Randles, D., & Tracy, J. L., 2013. Nonverbal displays of shame predict relapse and declining health in recovering alcoholics. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(2), 149-55. [DOI:10.1177/2167702612470645]

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L., 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68] [PMID]

Saadati Shamir, A., Mazboohi, S., & Marzi S., 2018. [A confirmatory factor analysis and validation of the forms of self-criticism/reassurance scale among teachers (Persian)]. Quarterly of Educational Measurement, 9(34), 133-47. [DOI:10.22054/JEM.2019.20805.1520]

Salvador, M. D. C., et al., 2017. Self-criticism and self-compassion in adolescents: two forms of self-relating and their implications for psychopathology and treatment. Turkiye Klinikleri J Child Psychiatry-Special Topics, 2(3), 132-8. https://eg.uc.pt/handle/10316/46647

Schimmenti, A., 2012. Unveiling the hidden self: Developmental trauma and pathological shame. Psychodynamic Practice, 18(2), 195-211. [DOI:10.1080/14753634.2012.664873]

Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M., 2005. Attachment theory and research: Resurrection of the psychodynamic approach to personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 39(1), 22-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2004.09.002]

Thompson, R., & Zuroff, D. C., 2004. The levels of self-criticism scale: Comparative self-criticism and internalized self-criticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(2), 419-30. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00106-5]

Tirch, D. D., 2010. Mindfulness as a context for the cultivation of compassion. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(2), 113-23. [DOI:10.1521/ijct.2010.3.2.113]

Weed, N. C., et al., 1992. New measures for assessing alcohol and drug abuse with the MMPI-2: The APS and AAS. Journal of Personality Assessment, 58(2), 389-404. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa5802_15] [PMID]

Whittle, S., et al., 2016. Neurodevelopmental correlates of proneness to guilt and shame in adolescence and early adulthood. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 19, 51-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.dcn.2016.02.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

Zargar, Y., Najarian, B. & Neami, A. Z., 2008. [Study the personality feature (sensation seeking, assertive enessand psychological hardiness), religious attitude, and marital satisfaction with the preparation of addiction potential among the staff of an industrial company in Ahvaz (Persian)]. Journal of Educational Sciences, 15(1), 99-120. https://www.sid.ir/fa/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=98530

Received: 2020/01/5 | Accepted: 2020/05/10 | Published: 2020/05/1

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |