Tue, Jul 16, 2024

[Archive]

Volume 8, Issue 3 (Summer 2022)

JCCNC 2022, 8(3): 177-190 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Bediako Agyei F, Nti F, Anago E K, Avinu E S. Grief and Coping Strategies of Nurses Following Patient Death at the Konongo-Odumasi Government Hospital, Ghana. JCCNC 2022; 8 (3) :177-190

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-365-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-365-en.html

1- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Presbyterian University College, Agogo, Ghana.

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Presbyterian University College, Agogo, Ghana. ,selasi.avinu@presbyuniversity.edu.gh

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Presbyterian University College, Agogo, Ghana. ,

Full-Text [PDF 727 kb]

(2177 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2091 Views)

Full-Text: (518 Views)

1. Introduction

Crief is a normal response to the loss of a significant thing or person, and it is the price we pay for love and commitment to each other (Hooyman & Kramer, 2006; Hall, 2011). Grief is experienced not only due to the death of a loved one but encompasses situations, such as divorce, adoption, and living with prolonged illness (Hooyman & Kramer, 2006). It is experienced in several forms, including physical, psychological, cognitive, behavioral, and spiritual manifestations (Hall, 2011). According to Sigmund Freud, grief is a survival process, through which the living break bond between themselves and dead loved ones. He thus proposed the first trajectory of grief involving three stages: (1) releasing the grieved from ties to the dead; (2) reformation to new life situations without the dead; and (3) forming new associations (Freud, 1957). Elizabeth Kubler-Ross later developed a new more accepted theory of grief, which states that grieving individuals navigate through five stages; denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance (Kübler-Ross, 1973).

The goal of nursing is to assist patients to recover from their ailments and, if not, to a peaceful death. Nurses are expected to demonstrate a high level of competency and skill in performing their professional tasks after a patient’s death (Meller et al., 2019). When patients are rushed to the hospital, they are expected to recover and survive their illness and improve their quality of life. This expectation is made possible majorly with the help of nurses who spend most of their time with these patients in their illness trajectory. This ongoing process of caring for patients every day makes nurses develop and feel some bond of commitment to their patients. However, not all patients are able to recover from their ailments and eventually die, notwithstanding the technological advancement and the efforts put up by the treatment team to keep them alive (Shorter & Stayt, 2010).

In Ghana, generally, when a patient dies in a ward, and this is confirmed by a doctor, the nurse is responsible for performing the last offices. The last offices refers to the care given to a body after death, which demonstrates respect for the deceased and is focused on respecting their religious and cultural beliefs, as well as health and safety and legal requirements (Higgins, 2010). The nursing responsibilities for the last offices in Ghana include preparation of the body for the mortuary and helping the relatives of the deceased through grief counseling. The family is then responsible for making the necessary plans to bury their loved ones based on their cultural and religious beliefs. The continual experience of a patient’s death in the presence of nurses predisposes them to the corporeal and psychological ramifications of grief (Shorter & Stayt, 2010). However, the unfortunate situation is that although most nurses grieve when patients die, their grief may be unrecognized (Jonas-Simpson et al., 2013). In a study on registered nurses in New Zealand, Kent et al. showed that the initial recollection of patients’ death occurs as early as in the first year of qualified practice. These deaths often occur in the acute medical and surgical wards leaving a lasting experience of guilt, meagerness, powerlessness, and distress on nurses that transcends to their professional and personal lives when left unaddressed (Kent, Anderson, & Owens, 2012). Nurses use some mechanisms to deal with the grief caused by the death of their patients to cope with this situation and the resulting pain and suffering. Some of the commonly used coping strategies by nurses in dealing with their grief include sharing and seeking support from colleagues, avoiding dying and death situations, engaging in spirituality, and compartmentalizing experience (Betriana & Kongsuwan, 2019; Gerow et al., 2010). Addressing the issue of nurses’ grief due to their patients’ deaths and understanding the coping approaches used will help them overcome these challenges in their careers.

Nurses’ grief has not been adequately addressed in most care settings, even though it is a well-known hazard to health and work performance (Khalaf et al., 2018). For example, some studies have explored nurses’ grief experiences in palliative care, pediatric nursing, and oncology settings (Reid, 2013; Adwan, 2014; Papadatou et al., 2002). However, research on the grief experiences of nurses working in other acute care hospital settings after the death of their patients is limited (Meller et al., 2019). In Ghana, nurses and midwives form the majority of health workers employed in the public sector. For example, in 2018, there were 67, 077 (58% of all healthcare workers) nurses and midwives employed in the public health sector of Ghana (Asamani et al., 2019). Nursing in Ghana is regulated by the Nurses and Midwifery Council (NMC) of Ghana. The NMC ensures that all nurses in Ghana have the license to practice as professional nurses after a one-year mandatory completion of National Service usually referred to as Rotation. Professional nurses have at least a diploma qualification in nursing and this category of nurses includes registered general nurses, registered midwives, registered mental health nurses, registered community health nurses, and post-basic nurses (Alhassan RK et al., 2020). The limited research on the hospital staff’s experiences of grief in Ghana has focused mainly on midwives (Dartey, Phuma-Ngaiyaye, & Phletlhu, 2017). No study has focused on the experience of different categories of nurses in Ghana. This study was done to examine grief and coping experiences amongst registered general nurses working in various care departments of a major government health facility in the Ashanti region of Ghana.

2. Material and Methods

It was a descriptive cross-sectional study that was conducted at the Konongo-Odumasi Government Hospital in Konongo. This is a 180-bed health facility and a National Health Insurance Scheme accredited hospital located in a mining community in the Ashanti Region, Ghana. The town serves as the capital of Asante Akyem Central Municipality. The hospital has the following departments to render effective service to its clients: an outpatient department, a pathological and research laboratory, a radiology department, a pharmaceutical department, a physiotherapy department, an emergency department, a dental department, medical ward, surgical ward, pediatric ward, maternity ward, and an operating theatre. The hospital is not affiliated with any university because it is a district hospital; however, physician assistantship and nursing students from the Presbyterian University College of Ghana have their vacation practicum at the hospital due to its proximity to the university campus.

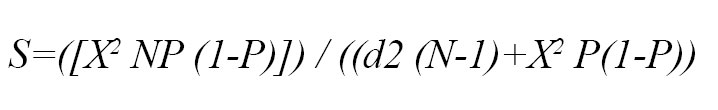

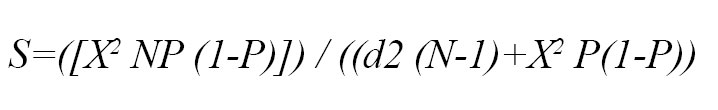

The sample size was calculated using the National Education Association formula:

, where, S= required sample size; X2=the table value of chi-square for one degree of freedom at the desired confidence level (i.e., (1.962) = 3.8416; N=the total population size= 99 nurses; P= the population prevalence of grief experience (i.e. assumed to be 0.50); and d= the degree of accuracy expressed as a proportion (i.e. 0.05) (Krejcie & Morgan, 1970).

Finally, 79 nurses were identified as the research sample. A quota sampling technique was then used to yield a representative sample of nurses working in different wards. The overall distribution of recruited nurses was as follows: medical ward (n=14), surgical ward (n=13), emergency ward (n=12), theatre (n=14), maternity ward (n=15), and pediatric ward (n=11). Therefore, the questionnaires were distributed in each stratum based on this calculation. The inclusion criteria were all registered nurses (in Ghana, it is mandatory for nurses to do a one-year national service after completion of training and after that, they are given the license to practice as registered/ professional nurses) at the stated wards of the hospital who were present during data collection and consented to participate in the study. All registered nurses on annual leave or excuse-duty were excluded from the study. Rotational nurses and student nurses were also excluded from the study.

The instrument used in data collection was a self-administered questionnaire, which was constructed through the study of authoritative texts and consultation with experts. The final questionnaire was adapted after pretesting among ten registered nurses working in a nearby health facility. The final questionnaire comprised of four sections. The first section had seven items to collect the demographic information of the subjects. The second and third sections were made of nine and seventeen items, respectively to collect information on the grief experiences of nurses after a patient’s death and its impacts, respectively. The fourth section with ten items obtained information on how nurses cope with grief after patients’ death.

Data were collected in a week to ensure all participants who worked on different shifts during the week had an equal chance of being selected.

Standard descriptive statistics (e.g., frequency and proportions) were used to summarize the survey data. Data management and analysis were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS software version 20).

3. Results

Demographic information

The characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The majority of the respondents were females (56%) and married (59.5%) and under 40 years of age (83.5%). About a third of the respondents were nursing officers, and most were Christians (76%). Only about a tenth of the respondents had worked for less than a year post-qualification.

Nurses’ experiences of grief after patient death

Information on the grief experiences of nurses surveyed is presented in Table 2.

.jpg)

The majority of respondents (63.3%) reported the experience of grief after the death of a patient, while about a third of respondents did not. Out of those who reported not experiencing grief, 48.2% (n=14) did not express their grief because of their professionalism, while another 40.7% (n=11) did not express their grief because of fear, and 11.1% (n=3) indicated no reason for not grieving. The majority of respondents (63%) also reported not feeling isolated when grieving after the loss of a patient. However, many respondents (51%) hid their grief when a patient died in their ward, and a similar proportion generally ignored their grief feelings. Furthermore, most respondents (63%) reported developing and building close, personal relationships with their patients, and 49.4% (n=39) of the respondents reported that they have experienced an overwhelming sense of loss when a patient died. Additionally, 83.5% (n=66) of the respondents reported that they were aware of patient suffering but were unable to relieve it due to the death of the patient.

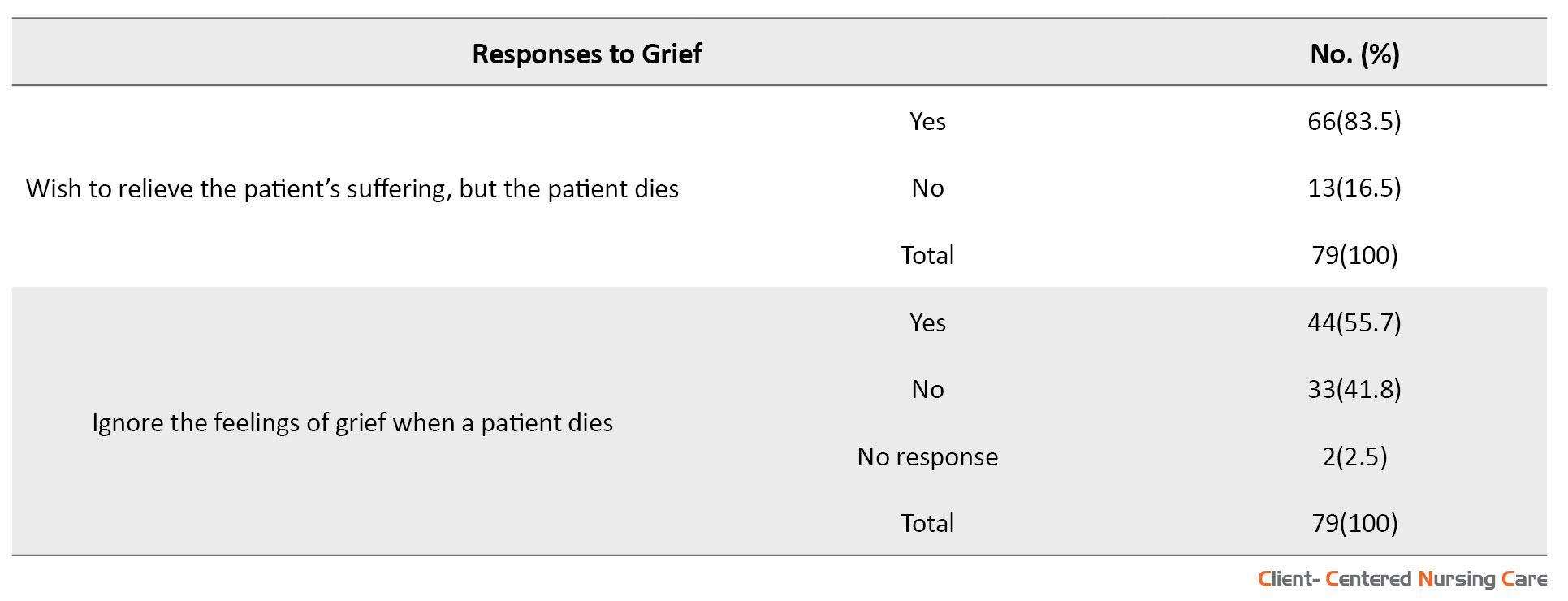

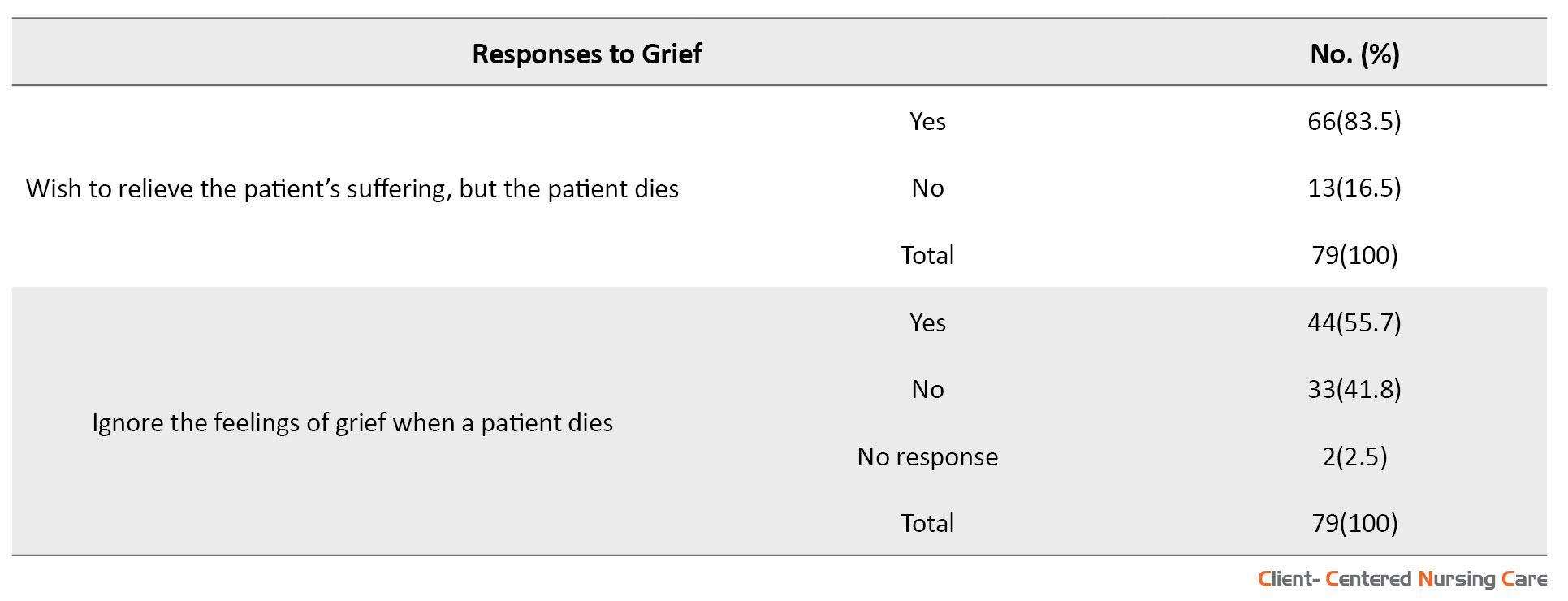

Impacts of grief following patients’ death on nurses

Nurses’ responses to the impacts of grieving after the death of their patients are presented in Table 3.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Some of the impacts reported included insomnia (39.2%), loss of appetite (50.6%), and tiredness (7.6%). Most respondents did not feel depressed (68.4%), did not experience feelings of uneasiness and being easily bothered (55.7%), and responded that the grief did not affect their functionality both at work and at home (65.8%). Only about a third of the respondents reported having feelings of uneasiness and being easily bothered, sleeping late at night, waking up too early, and generally feeling irritable and emotionally overwhelmed following the death of a patient. Furthermore, less than a fifth of the respondents reported feeling burnout, physically unwell or anxious, abusing alcohol, having low self-esteem, and being absent from work following patients’ death. Only a few respondents (less than 10%) reported a decrease in quality of patient care, suicidal thoughts, and a decision to leave the workplace.

Nurses’ coping with grief after a patient’s death

The answers to the questions related to coping strategies adopted by nurses after the patient’s death are presented in Table 4.

.jpg)

Most nurses (75.9%) were aware that when they do not recognize grief and cope appropriately, it could explode at any time. Consequently, most of them (75.9%) find activities and practices that replenish, comfort, and revitalize their spirit when a patient dies. The activities reported were engaging in exercise (66.7%), going to church (3.3%), reading the Bible or Quran (8.3%), other spiritual practices, such as meditation or prayers (50.6%), engaging in whatever promotes rest and comfort, such as swimming (16.7%). Furthermore, around half of the respondents listened to music as a coping strategy. About a third of the respondents attended the funeral celebration of the deceased patient. Most respondents did not put away their stethoscope ( i.e. they did not quit providing nursing care to other patients) (86.1%) or change clothes (75.9%) to cope with grief. Instead, some (41.8%) talked about their feelings or interacted with other professionals to cope with grief. Almost half of the respondents indicated that they have access to professional counseling to cope with grief.

4. Discussion

The present study revealed that nurses grieve when a patient dies. However, most of them did not show it or did not recognize that they are grieving. This finding is consistent with that of Jonas-Simpson et al. (2013) reporting that the unfortunate situation is that although most nurses grieve when patients die, their grief is unrecognized. Therefore, nursing faculty, administrators, and leaders could offer a more conducive and supportive practice environment for professional nurses by developing an in-depth understanding of and acknowledging the grieving process (Gerow et al., 2010; Shorter and Stayt, 2010; Jonas-Simpson et al., 2013).

The current study revealed the reason why nurses hide their grief was professionalism. This means that nurses have to develop some resistance to grief to continue the caring process for their patients. Previous studies also have shown that nurses develop a protection screen to lessen grieving and provide ongoing supportive care to patients (Gerow et al., 2010; Jonas-Simpson et al., 2013; Shorter and Stayt, 2010; MacDermott & Keenan, 2014). However, these experiences tend to have a long-term impact on the nurses’ personal and professional lives; hence, they require in-depth understanding to assist them in proper adjustment (Kent et al. 2012).

The finding that nurses experience sorrow and trauma when they care for a patient who passed away corresponds to the study of Couden (2002). This is because nurses develop and build close and personal relationships with patients when caring for them and, as a result, experience a devastating sense of loss. The current study showed the impacts of nurses’ grief, such as insomnia, loss of appetite, tiredness, and social isolation. These findings are consistent with a qualitative explorative study in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, which included a purposive sample of 18 ward supervisors and 39 ward midwives (Dartey et al., 2017).

Inconsistent with the findings of other studies (Moussavi et al., 2007; Fuchs, 2013), most nurses in this study did not report experiencing depression due to grief. However, it is noteworthy that depression may be expressed as insomnia, loss of appetite, exhaustion, and social isolation (Braun et al., 2007; Given et al., 2004; Dartey & Phuma-Ngaiyaye, 2020), which the study participants reported. Similarly, unlike what has been established in other studies (Aycock & Boyle, 2009; Benca & Peterson, 2008), for most nurses in this study, their functionality at work and at home was not affected by grief. This may be related to their coping strategies, such as strategies for revitalizing their spirit. However, this may also indicate a lack of self-awareness amongst nurses in our study.

Poorly managed grief experiences amongst nurses have been shown to result in absenteeism and alcohol abuse (Yoon, 2009; Kim & Park, 2012). However, the finding that most nurses in the present study did not use alcohol due to depression or did not experience low self-esteem and absenteeism due to grief over the patient’s death may indicate good grief management strategies. Continual exposure to death and grief may progress to work-related stress and eventually burnout. However, most nurses in the study did not experience burnout due to grief over patients’ death. Meert (2011) explains that although caregivers experience a high level of complicated grief, some can integrate it into their daily lives, allowing them to continue caregiving. It is thus not surprising that most nurses have not experienced a decrease in the quality of patient care due to grief over patients’ death. It is, however, established that nurses may experience compassion fatigue in their daily practice, which, if left unresolved, can significantly impact their professional and personal lives and lead to a decrease in the quality of care (Aycock & Boyle, 2009; Coetzee & Klopper, 2010; Showalter, 2010).

Regarding how nurses cope with grief, the current study revealed that the respondents were aware that when they do not recognize grief and cope appropriately, it explodes at any time, which is in line with the study by Lally (2005), reporting that the first stage of mitigating the impacts of grief is early recognition. When there is a failure to recognize these griefs, they can explode abruptly (Wakefield, 2000).

Most nurses in our study consciously resorted to activities and practices that replenish, comfort, and revitalize their spirit after a patient death. These activities and practices were exercise, family or religious activities (going to church), and spirituality (reading the Bible/ Quran). These are consistent with other studies that reported that nurses find spirituality significant in their daily lives (75%) and it assists them in coping with grief over patients’ death (70%) (Shinbara & Olson, 2010). This is further echoed in the study by Bush (2009) reporting that identifying activities and practices in nursing care that refill, relief, and refresh the spirits is ideal for assisting nurses to overcome their grief. These activities might include engaging with the family or religion, spirituality, or whatever the individual might find restful and comfortable (Austin et al., 2009; Pipe & Bortz, 2009; Showalter, 2010).

Furthermore, we found that nurses engage in spiritual practices, such as meditation, prayer, and quiet time to cope with grief and they do not attend funerals of the patients and do not send sympathy cards to cope with grief. These are similar to other studies that have found that nurses’ faith and religion protect them from the accumulated consequences of grief (Aycock & Boyle, 2009; Shinbara & Olson, 2010). However, for some nurses, insight and personal experience assist them in coping well with grief (Maytum, Heiman, & Garwick, 2004). Also, recognizing deaths by appearing at the funerals of the bereaved and sending sympathy cards may assist nurses’ grief properly (Medland et al., 2004). Furthermore, Fetter (2012) posited that recognizing bereavement and engaging in discussions may assist nurses in mitigating grief.

Additionally, the current study found that nurses discuss emotions or interact with other professionals to cope with grief. Nurses sometimes isolate themselves and are incapacitated to discuss their grief when patients die (Papadatou, 2000). This unsupportive atmosphere may result in nurses tending to vacate the profession or the ward (Shinbara & Olson, 2010). However, when the working atmosphere is supportive, nurses find meaning in grief experiences (Lally, 2005). Furthermore, avenues to discuss emotional feelings of grief with other professionals during breaks or lunch may offer emotional support to nurses after their last offices (Papadatou, 2000). Examples of these avenues include organized support groups or debriefings. Skilled professionals should spear these discussions and encourage nurses to discuss supportive coping mechanisms with other team members (Keene et al., 2010; Hall, 2011; Medland et al., 2004).

Despite the utility of the findings of this study, one must consider the following limitations of the study. Firstly, as a cross-sectional study, the findings only give a snapshot of the situation at the time of the study. In addition, depending on the culture of nursing in Ghana, different findings may emerge in other countries. Furthermore, as it is with all studies relying on self-reported data, the respondents may have under-reported their true grief experiences after the loss of a patient. To confirm and further improve our understanding of the grief experiences of registered nurses, future research should include methods that allow for direct observation of nurses after the loss of a patient and in-depth interviews with colleagues and housemates.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides further evidence that nurses working in different care settings in Ghana respond emotionally to patients’ death and experience grief. Most nurses are aware of the effects repeated grief has on their personal and professional lives and thus develop individualized coping habits to manage grief. Only a few nurses reported access to professional counseling support for dealing with grief. Regular training on effective grief coping strategies and professional emotional support should be provided to nurses caring for dying patients. This will undoubtedly improve the health and wellbeing of nurses and also the quality of care for both dying patients and their families.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences of Presbyterian University College, Ghana, and conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Adequate information was given to the participants regarding the research objectives, benefits, risks, and voluntary participation in the study. Approval was sought from the study hospital, and signed informed consent was obtained from participants before data collection. The collected data were kept confidential and anonymized. Coding systems were developed to ensure that data sources were identifiable only by the researcher.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors reported no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the staff and nurses at the Konongo-Odumasi Government Hospital for their time and participation in the study.

References

Adwan, J. Z., 2014. Pediatric nurses’ grief experience, burnout and job satisfaction. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29(4), pp. 329–36. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2014.01.011] [PMID]

Alhassan R. K., et al., 2020. Implementation of the policy protocol for management of surgical and non- surgical wounds in selected public health facilities in Ghana: An analytic case study. PloS One, 15(6), pp. e0234874. [PMID] [PMCID]

AAsamani, J. A., et al., 2019. Nurses and midwives demographic shift in Ghana-the policy implications of a looming crisis. Human Resources for Health, 17(1), pp. 32. [PMID] [PMCID]

Austin, W., et al., 2009. Compassion fatigue: The experience of nurses. Ethics and Social Welfare, 3(2), pp. 195-214.[DOI:10.1080/17496530902951988]

Aycock, N. & Boyle, D., 2009. Interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nursing. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 13(2), pp. 183-91. [PMID]

Benca, R. M. & Peterson, M. J., 2008. Insomnia and depression. Sleep Medicine, 9(Supplement 1), pp. S3-9. [DOI:10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70010-8]

Betriana, F. & Kongsuwan, W., 2019. Grief reactions and coping strategies of Muslim nurses dealing with death. Nursing in Critical Care, 25 (5), pp. 277-83. [DOI:10.1111/nicc.12481] [PMID]

Braun, M., et al., 2007. Hidden morbidity in cancer: Spouse caregivers. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(30), pp. 4829–34. [DOI:10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909] [PMID]

Bush N. J., 2009. Compassion fatigue: Are you at risk? Oncology Nursing Forum, 36(1), 24–28. [DOI:10.1188/09.ONF.24-28] [PMID]

Coetzee, S. K. & Klopper, H. C., 2010. Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: A concept analysis. Nursing & Health Sciences, 12(2), pp. 235-43. [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00526.x] [PMID]

Couden, B. A. (2002). “Sometimes I want to run”: A nurses reflects on loss in the intensive care unit. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 7, 35-45. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/108114402753344472

Dartey, A. F. & Phuma-Ngaiyaye, E., 2020. Physical effects of maternal deaths on midwives’ health: A qualitative approach. Journal of Pregnancy, 2020, pp. 2606798. [DOI:10.1155/2020/2606798] [PMID] [PMCID]

Dartey, A. F., Phuma-Ngaiyaye, E. E. & Phletlhu, D. R., 2017. Effects of death as a unique experience among midwives in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. International Journal of Health and Sciences Research, 7(12), pp. 158-67. [Link]

Fetter, K. L., 2012. We grieve too: One inpatient oncology unit's interventions for recognizing and combating compassion fatigue. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16(6), 559–561.[DOI:10.1188/12.CJON.559-561] [PMID]

Fuchs, T., 2013. Depression, intercorporeality, and interaffectivity. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 20(7-8), pp. 219-38. [Link]

Gerow, L., et al., 2010. Creating a curtain of protection: Nurses’ experiences of grief following patient death. Journal of nursing scholarship, 42(2), pp. 122–9. [DOI:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01343.x] [PMID]

Given, B., et al., 2004. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end-of-life. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31(6), pp. 1105–17. [PMID] [PMCID]

Hall, C., 2011. Beyond Kübler-Ross: Recent developments in our understanding of grief and bereavement. InPsych. The Bulletin of the Australian Psychological Society Ltd, 33(6), pp. 8-11. [DOI:10.1080/02682621.2014.902610]

Higgins, D., 2009. Last offices. In P. Jevon (Ed.), Care of the dying and deceased patient: A practical guide for nurses. New York: Wiley. [Link]

Hooyman, N. R., & Kramer, B. J., 2008. Living through loss: Interventions across the life span. New York: Columbia University Press. [Link]

Jonas-Simpson, C., et al., 2013. Nurses’ experiences of grieving when there is a perinatal death. Sage Open, 3(2), pp. 1-11. [DOI:10.1177/2158244013486116]

Keene, E. A., et al., 2010. Bereavement debriefing sessions: An intervention to support health care professionals in managing their grief after the death of a patient. Pediatric Nursing, 36(4), pp. 185-9. [Link]

Kent, B., Anderson, N. E. & Owens, R. G., 2012. Nurses’ early experiences with patient death: The results of an on-line survey of Registered Nurses in New Zealand. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(10), pp. 1255–65. [PMID]

Khalaf, I. A., et al., 2018. Nurses’ experiences of grief following patient death: A qualitative approach. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 36(3), pp. 228–40. [DOI:10.1177/0898010117720341] [PMID]

Kim, J. H. & Park, E., 2012. The effect of job-stress and self-efficacy on depression of clinical nurses. Korean Journal of Occupational Health Nursing, 21(2), pp. 134-44. [DOI:10.5807/kjohn.2012.21.2.134]

Krejcie R. V., & Morgan, D. W., 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Education and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), pp. 607-10. [DOI:10.1177/001316447003000308]

Kübler-Ross, E., 1973. On death and dying. London: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9780203010495]

Lally, R. M., 2005. Oncology nurses share their experiences with bereavement and self-care. Ons News, 20(10), pp. 4-11. [PMID]

MacDermott, C. & Keenan, P. M., 2014. Grief experiences of nurses in Ireland who have cared for children with an intellectual disability who have died. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 20(12), pp. 584–90. [DOI:10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.12.584] [PMID]

Maytum, J. C., Heiman, M. B. & Garwick, A. W., 2004. Compassion fatigue and burnout in nurses who work with children with chronic conditions and their families. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 18(4), 171-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedhc.2003.12.005] [PMID]

Medland, J., Howard-Ruben, J. & Whitaker, E., (2004). Fostering psychosocial wellness in oncology nurses: Addressing burnout and social support in the workplace. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31(1), pp. 47–54. [PMID]

Meert, K. L., et al., 2011. Follow-up study of complicated grief among parents eighteen months after a child's death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 14(2), 207-214. [DOI:10.1089/jpm.2010.0291] [PMID] [PMCID]

Meller, N., et al., 2019. Grief experiences of nurses after the death of an adult patient in an acute hospital setting: An integrative review of literature. Collegian, 26(2), pp. 302-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.colegn.2018.07.011]

Moussavi, S., et al., 2007. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: Results from the World Health Surveys. The Lancet, 370(9590), pp. 851-8. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9]

Papadatou, D., 2000. A proposed model of health professionals’ grieving process. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 41(1), pp. 59-77. [DOI:10.2190/TV6M-8YNA-5DYW-3C1E]

Papadatou, D., et al., 2002. Greek nurse and physician grief as a result of caring for children dying of cancer. Pediatric Nursing, 28(4), pp. 345–53. [PMID]

Pipe, T. B. & Bortz, J. J., 2009. Mindful leadership as healing practice: Nurturing self to serve others. International Journal for Human Caring, 13(2), pp. 34-8. [DOI:10.20467/1091-5710.13.2.34]

Reid F., 2013. Grief and the experiences of nurses providing palliative care to children and young people at home. Nursing Children and Young People, 25(9), pp. 31-6. [PMID]

Shinbara, C. G. & Olson, L., 2010. When nurses grieve: Spirituality’s role in coping. Journal of Christian Nursing: A Quarterly Publication of Nurses Christian Fellowship, 27(1), pp. 32-7. [PMID]

Shorter, M. & Stayt, L. C., 2010. Critical care nurses’ experiences of grief in an adult intensive care unit. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(1), pp. 159–67. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05191.x] [PMID]

Showalter, S. E., 2010. Compassion fatigue: What is it? Why does it matter? Recognizing the symptoms, acknowledging the impact, developing the tools to prevent compassion fatigue, and strengthen the professional already suffering from the effects. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 27(4), pp. 239–42. [DOI:10.1177/1049909109354096] [PMID]

Wakefield A., 2000. Nurses’ responses to death and dying: A need for relentless self-care. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 6(5), pp. 245–51. [PMID]

Yoon, S. H., 2009. Occupational stress and depression in clinical nurses-using Korean occupational stress scales. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration, 15(3), pp. 463-70.

Crief is a normal response to the loss of a significant thing or person, and it is the price we pay for love and commitment to each other (Hooyman & Kramer, 2006; Hall, 2011). Grief is experienced not only due to the death of a loved one but encompasses situations, such as divorce, adoption, and living with prolonged illness (Hooyman & Kramer, 2006). It is experienced in several forms, including physical, psychological, cognitive, behavioral, and spiritual manifestations (Hall, 2011). According to Sigmund Freud, grief is a survival process, through which the living break bond between themselves and dead loved ones. He thus proposed the first trajectory of grief involving three stages: (1) releasing the grieved from ties to the dead; (2) reformation to new life situations without the dead; and (3) forming new associations (Freud, 1957). Elizabeth Kubler-Ross later developed a new more accepted theory of grief, which states that grieving individuals navigate through five stages; denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance (Kübler-Ross, 1973).

The goal of nursing is to assist patients to recover from their ailments and, if not, to a peaceful death. Nurses are expected to demonstrate a high level of competency and skill in performing their professional tasks after a patient’s death (Meller et al., 2019). When patients are rushed to the hospital, they are expected to recover and survive their illness and improve their quality of life. This expectation is made possible majorly with the help of nurses who spend most of their time with these patients in their illness trajectory. This ongoing process of caring for patients every day makes nurses develop and feel some bond of commitment to their patients. However, not all patients are able to recover from their ailments and eventually die, notwithstanding the technological advancement and the efforts put up by the treatment team to keep them alive (Shorter & Stayt, 2010).

In Ghana, generally, when a patient dies in a ward, and this is confirmed by a doctor, the nurse is responsible for performing the last offices. The last offices refers to the care given to a body after death, which demonstrates respect for the deceased and is focused on respecting their religious and cultural beliefs, as well as health and safety and legal requirements (Higgins, 2010). The nursing responsibilities for the last offices in Ghana include preparation of the body for the mortuary and helping the relatives of the deceased through grief counseling. The family is then responsible for making the necessary plans to bury their loved ones based on their cultural and religious beliefs. The continual experience of a patient’s death in the presence of nurses predisposes them to the corporeal and psychological ramifications of grief (Shorter & Stayt, 2010). However, the unfortunate situation is that although most nurses grieve when patients die, their grief may be unrecognized (Jonas-Simpson et al., 2013). In a study on registered nurses in New Zealand, Kent et al. showed that the initial recollection of patients’ death occurs as early as in the first year of qualified practice. These deaths often occur in the acute medical and surgical wards leaving a lasting experience of guilt, meagerness, powerlessness, and distress on nurses that transcends to their professional and personal lives when left unaddressed (Kent, Anderson, & Owens, 2012). Nurses use some mechanisms to deal with the grief caused by the death of their patients to cope with this situation and the resulting pain and suffering. Some of the commonly used coping strategies by nurses in dealing with their grief include sharing and seeking support from colleagues, avoiding dying and death situations, engaging in spirituality, and compartmentalizing experience (Betriana & Kongsuwan, 2019; Gerow et al., 2010). Addressing the issue of nurses’ grief due to their patients’ deaths and understanding the coping approaches used will help them overcome these challenges in their careers.

Nurses’ grief has not been adequately addressed in most care settings, even though it is a well-known hazard to health and work performance (Khalaf et al., 2018). For example, some studies have explored nurses’ grief experiences in palliative care, pediatric nursing, and oncology settings (Reid, 2013; Adwan, 2014; Papadatou et al., 2002). However, research on the grief experiences of nurses working in other acute care hospital settings after the death of their patients is limited (Meller et al., 2019). In Ghana, nurses and midwives form the majority of health workers employed in the public sector. For example, in 2018, there were 67, 077 (58% of all healthcare workers) nurses and midwives employed in the public health sector of Ghana (Asamani et al., 2019). Nursing in Ghana is regulated by the Nurses and Midwifery Council (NMC) of Ghana. The NMC ensures that all nurses in Ghana have the license to practice as professional nurses after a one-year mandatory completion of National Service usually referred to as Rotation. Professional nurses have at least a diploma qualification in nursing and this category of nurses includes registered general nurses, registered midwives, registered mental health nurses, registered community health nurses, and post-basic nurses (Alhassan RK et al., 2020). The limited research on the hospital staff’s experiences of grief in Ghana has focused mainly on midwives (Dartey, Phuma-Ngaiyaye, & Phletlhu, 2017). No study has focused on the experience of different categories of nurses in Ghana. This study was done to examine grief and coping experiences amongst registered general nurses working in various care departments of a major government health facility in the Ashanti region of Ghana.

2. Material and Methods

It was a descriptive cross-sectional study that was conducted at the Konongo-Odumasi Government Hospital in Konongo. This is a 180-bed health facility and a National Health Insurance Scheme accredited hospital located in a mining community in the Ashanti Region, Ghana. The town serves as the capital of Asante Akyem Central Municipality. The hospital has the following departments to render effective service to its clients: an outpatient department, a pathological and research laboratory, a radiology department, a pharmaceutical department, a physiotherapy department, an emergency department, a dental department, medical ward, surgical ward, pediatric ward, maternity ward, and an operating theatre. The hospital is not affiliated with any university because it is a district hospital; however, physician assistantship and nursing students from the Presbyterian University College of Ghana have their vacation practicum at the hospital due to its proximity to the university campus.

The sample size was calculated using the National Education Association formula:

, where, S= required sample size; X2=the table value of chi-square for one degree of freedom at the desired confidence level (i.e., (1.962) = 3.8416; N=the total population size= 99 nurses; P= the population prevalence of grief experience (i.e. assumed to be 0.50); and d= the degree of accuracy expressed as a proportion (i.e. 0.05) (Krejcie & Morgan, 1970).

Finally, 79 nurses were identified as the research sample. A quota sampling technique was then used to yield a representative sample of nurses working in different wards. The overall distribution of recruited nurses was as follows: medical ward (n=14), surgical ward (n=13), emergency ward (n=12), theatre (n=14), maternity ward (n=15), and pediatric ward (n=11). Therefore, the questionnaires were distributed in each stratum based on this calculation. The inclusion criteria were all registered nurses (in Ghana, it is mandatory for nurses to do a one-year national service after completion of training and after that, they are given the license to practice as registered/ professional nurses) at the stated wards of the hospital who were present during data collection and consented to participate in the study. All registered nurses on annual leave or excuse-duty were excluded from the study. Rotational nurses and student nurses were also excluded from the study.

The instrument used in data collection was a self-administered questionnaire, which was constructed through the study of authoritative texts and consultation with experts. The final questionnaire was adapted after pretesting among ten registered nurses working in a nearby health facility. The final questionnaire comprised of four sections. The first section had seven items to collect the demographic information of the subjects. The second and third sections were made of nine and seventeen items, respectively to collect information on the grief experiences of nurses after a patient’s death and its impacts, respectively. The fourth section with ten items obtained information on how nurses cope with grief after patients’ death.

Data were collected in a week to ensure all participants who worked on different shifts during the week had an equal chance of being selected.

Standard descriptive statistics (e.g., frequency and proportions) were used to summarize the survey data. Data management and analysis were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS software version 20).

3. Results

Demographic information

The characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The majority of the respondents were females (56%) and married (59.5%) and under 40 years of age (83.5%). About a third of the respondents were nursing officers, and most were Christians (76%). Only about a tenth of the respondents had worked for less than a year post-qualification.

Nurses’ experiences of grief after patient death

Information on the grief experiences of nurses surveyed is presented in Table 2.

.jpg)

The majority of respondents (63.3%) reported the experience of grief after the death of a patient, while about a third of respondents did not. Out of those who reported not experiencing grief, 48.2% (n=14) did not express their grief because of their professionalism, while another 40.7% (n=11) did not express their grief because of fear, and 11.1% (n=3) indicated no reason for not grieving. The majority of respondents (63%) also reported not feeling isolated when grieving after the loss of a patient. However, many respondents (51%) hid their grief when a patient died in their ward, and a similar proportion generally ignored their grief feelings. Furthermore, most respondents (63%) reported developing and building close, personal relationships with their patients, and 49.4% (n=39) of the respondents reported that they have experienced an overwhelming sense of loss when a patient died. Additionally, 83.5% (n=66) of the respondents reported that they were aware of patient suffering but were unable to relieve it due to the death of the patient.

Impacts of grief following patients’ death on nurses

Nurses’ responses to the impacts of grieving after the death of their patients are presented in Table 3.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Some of the impacts reported included insomnia (39.2%), loss of appetite (50.6%), and tiredness (7.6%). Most respondents did not feel depressed (68.4%), did not experience feelings of uneasiness and being easily bothered (55.7%), and responded that the grief did not affect their functionality both at work and at home (65.8%). Only about a third of the respondents reported having feelings of uneasiness and being easily bothered, sleeping late at night, waking up too early, and generally feeling irritable and emotionally overwhelmed following the death of a patient. Furthermore, less than a fifth of the respondents reported feeling burnout, physically unwell or anxious, abusing alcohol, having low self-esteem, and being absent from work following patients’ death. Only a few respondents (less than 10%) reported a decrease in quality of patient care, suicidal thoughts, and a decision to leave the workplace.

Nurses’ coping with grief after a patient’s death

The answers to the questions related to coping strategies adopted by nurses after the patient’s death are presented in Table 4.

.jpg)

Most nurses (75.9%) were aware that when they do not recognize grief and cope appropriately, it could explode at any time. Consequently, most of them (75.9%) find activities and practices that replenish, comfort, and revitalize their spirit when a patient dies. The activities reported were engaging in exercise (66.7%), going to church (3.3%), reading the Bible or Quran (8.3%), other spiritual practices, such as meditation or prayers (50.6%), engaging in whatever promotes rest and comfort, such as swimming (16.7%). Furthermore, around half of the respondents listened to music as a coping strategy. About a third of the respondents attended the funeral celebration of the deceased patient. Most respondents did not put away their stethoscope ( i.e. they did not quit providing nursing care to other patients) (86.1%) or change clothes (75.9%) to cope with grief. Instead, some (41.8%) talked about their feelings or interacted with other professionals to cope with grief. Almost half of the respondents indicated that they have access to professional counseling to cope with grief.

4. Discussion

The present study revealed that nurses grieve when a patient dies. However, most of them did not show it or did not recognize that they are grieving. This finding is consistent with that of Jonas-Simpson et al. (2013) reporting that the unfortunate situation is that although most nurses grieve when patients die, their grief is unrecognized. Therefore, nursing faculty, administrators, and leaders could offer a more conducive and supportive practice environment for professional nurses by developing an in-depth understanding of and acknowledging the grieving process (Gerow et al., 2010; Shorter and Stayt, 2010; Jonas-Simpson et al., 2013).

The current study revealed the reason why nurses hide their grief was professionalism. This means that nurses have to develop some resistance to grief to continue the caring process for their patients. Previous studies also have shown that nurses develop a protection screen to lessen grieving and provide ongoing supportive care to patients (Gerow et al., 2010; Jonas-Simpson et al., 2013; Shorter and Stayt, 2010; MacDermott & Keenan, 2014). However, these experiences tend to have a long-term impact on the nurses’ personal and professional lives; hence, they require in-depth understanding to assist them in proper adjustment (Kent et al. 2012).

The finding that nurses experience sorrow and trauma when they care for a patient who passed away corresponds to the study of Couden (2002). This is because nurses develop and build close and personal relationships with patients when caring for them and, as a result, experience a devastating sense of loss. The current study showed the impacts of nurses’ grief, such as insomnia, loss of appetite, tiredness, and social isolation. These findings are consistent with a qualitative explorative study in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, which included a purposive sample of 18 ward supervisors and 39 ward midwives (Dartey et al., 2017).

Inconsistent with the findings of other studies (Moussavi et al., 2007; Fuchs, 2013), most nurses in this study did not report experiencing depression due to grief. However, it is noteworthy that depression may be expressed as insomnia, loss of appetite, exhaustion, and social isolation (Braun et al., 2007; Given et al., 2004; Dartey & Phuma-Ngaiyaye, 2020), which the study participants reported. Similarly, unlike what has been established in other studies (Aycock & Boyle, 2009; Benca & Peterson, 2008), for most nurses in this study, their functionality at work and at home was not affected by grief. This may be related to their coping strategies, such as strategies for revitalizing their spirit. However, this may also indicate a lack of self-awareness amongst nurses in our study.

Poorly managed grief experiences amongst nurses have been shown to result in absenteeism and alcohol abuse (Yoon, 2009; Kim & Park, 2012). However, the finding that most nurses in the present study did not use alcohol due to depression or did not experience low self-esteem and absenteeism due to grief over the patient’s death may indicate good grief management strategies. Continual exposure to death and grief may progress to work-related stress and eventually burnout. However, most nurses in the study did not experience burnout due to grief over patients’ death. Meert (2011) explains that although caregivers experience a high level of complicated grief, some can integrate it into their daily lives, allowing them to continue caregiving. It is thus not surprising that most nurses have not experienced a decrease in the quality of patient care due to grief over patients’ death. It is, however, established that nurses may experience compassion fatigue in their daily practice, which, if left unresolved, can significantly impact their professional and personal lives and lead to a decrease in the quality of care (Aycock & Boyle, 2009; Coetzee & Klopper, 2010; Showalter, 2010).

Regarding how nurses cope with grief, the current study revealed that the respondents were aware that when they do not recognize grief and cope appropriately, it explodes at any time, which is in line with the study by Lally (2005), reporting that the first stage of mitigating the impacts of grief is early recognition. When there is a failure to recognize these griefs, they can explode abruptly (Wakefield, 2000).

Most nurses in our study consciously resorted to activities and practices that replenish, comfort, and revitalize their spirit after a patient death. These activities and practices were exercise, family or religious activities (going to church), and spirituality (reading the Bible/ Quran). These are consistent with other studies that reported that nurses find spirituality significant in their daily lives (75%) and it assists them in coping with grief over patients’ death (70%) (Shinbara & Olson, 2010). This is further echoed in the study by Bush (2009) reporting that identifying activities and practices in nursing care that refill, relief, and refresh the spirits is ideal for assisting nurses to overcome their grief. These activities might include engaging with the family or religion, spirituality, or whatever the individual might find restful and comfortable (Austin et al., 2009; Pipe & Bortz, 2009; Showalter, 2010).

Furthermore, we found that nurses engage in spiritual practices, such as meditation, prayer, and quiet time to cope with grief and they do not attend funerals of the patients and do not send sympathy cards to cope with grief. These are similar to other studies that have found that nurses’ faith and religion protect them from the accumulated consequences of grief (Aycock & Boyle, 2009; Shinbara & Olson, 2010). However, for some nurses, insight and personal experience assist them in coping well with grief (Maytum, Heiman, & Garwick, 2004). Also, recognizing deaths by appearing at the funerals of the bereaved and sending sympathy cards may assist nurses’ grief properly (Medland et al., 2004). Furthermore, Fetter (2012) posited that recognizing bereavement and engaging in discussions may assist nurses in mitigating grief.

Additionally, the current study found that nurses discuss emotions or interact with other professionals to cope with grief. Nurses sometimes isolate themselves and are incapacitated to discuss their grief when patients die (Papadatou, 2000). This unsupportive atmosphere may result in nurses tending to vacate the profession or the ward (Shinbara & Olson, 2010). However, when the working atmosphere is supportive, nurses find meaning in grief experiences (Lally, 2005). Furthermore, avenues to discuss emotional feelings of grief with other professionals during breaks or lunch may offer emotional support to nurses after their last offices (Papadatou, 2000). Examples of these avenues include organized support groups or debriefings. Skilled professionals should spear these discussions and encourage nurses to discuss supportive coping mechanisms with other team members (Keene et al., 2010; Hall, 2011; Medland et al., 2004).

Despite the utility of the findings of this study, one must consider the following limitations of the study. Firstly, as a cross-sectional study, the findings only give a snapshot of the situation at the time of the study. In addition, depending on the culture of nursing in Ghana, different findings may emerge in other countries. Furthermore, as it is with all studies relying on self-reported data, the respondents may have under-reported their true grief experiences after the loss of a patient. To confirm and further improve our understanding of the grief experiences of registered nurses, future research should include methods that allow for direct observation of nurses after the loss of a patient and in-depth interviews with colleagues and housemates.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides further evidence that nurses working in different care settings in Ghana respond emotionally to patients’ death and experience grief. Most nurses are aware of the effects repeated grief has on their personal and professional lives and thus develop individualized coping habits to manage grief. Only a few nurses reported access to professional counseling support for dealing with grief. Regular training on effective grief coping strategies and professional emotional support should be provided to nurses caring for dying patients. This will undoubtedly improve the health and wellbeing of nurses and also the quality of care for both dying patients and their families.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences of Presbyterian University College, Ghana, and conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Adequate information was given to the participants regarding the research objectives, benefits, risks, and voluntary participation in the study. Approval was sought from the study hospital, and signed informed consent was obtained from participants before data collection. The collected data were kept confidential and anonymized. Coding systems were developed to ensure that data sources were identifiable only by the researcher.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors reported no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the staff and nurses at the Konongo-Odumasi Government Hospital for their time and participation in the study.

References

Adwan, J. Z., 2014. Pediatric nurses’ grief experience, burnout and job satisfaction. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29(4), pp. 329–36. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2014.01.011] [PMID]

Alhassan R. K., et al., 2020. Implementation of the policy protocol for management of surgical and non- surgical wounds in selected public health facilities in Ghana: An analytic case study. PloS One, 15(6), pp. e0234874. [PMID] [PMCID]

AAsamani, J. A., et al., 2019. Nurses and midwives demographic shift in Ghana-the policy implications of a looming crisis. Human Resources for Health, 17(1), pp. 32. [PMID] [PMCID]

Austin, W., et al., 2009. Compassion fatigue: The experience of nurses. Ethics and Social Welfare, 3(2), pp. 195-214.[DOI:10.1080/17496530902951988]

Aycock, N. & Boyle, D., 2009. Interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nursing. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 13(2), pp. 183-91. [PMID]

Benca, R. M. & Peterson, M. J., 2008. Insomnia and depression. Sleep Medicine, 9(Supplement 1), pp. S3-9. [DOI:10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70010-8]

Betriana, F. & Kongsuwan, W., 2019. Grief reactions and coping strategies of Muslim nurses dealing with death. Nursing in Critical Care, 25 (5), pp. 277-83. [DOI:10.1111/nicc.12481] [PMID]

Braun, M., et al., 2007. Hidden morbidity in cancer: Spouse caregivers. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(30), pp. 4829–34. [DOI:10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909] [PMID]

Bush N. J., 2009. Compassion fatigue: Are you at risk? Oncology Nursing Forum, 36(1), 24–28. [DOI:10.1188/09.ONF.24-28] [PMID]

Coetzee, S. K. & Klopper, H. C., 2010. Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: A concept analysis. Nursing & Health Sciences, 12(2), pp. 235-43. [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00526.x] [PMID]

Couden, B. A. (2002). “Sometimes I want to run”: A nurses reflects on loss in the intensive care unit. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 7, 35-45. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/108114402753344472

Dartey, A. F. & Phuma-Ngaiyaye, E., 2020. Physical effects of maternal deaths on midwives’ health: A qualitative approach. Journal of Pregnancy, 2020, pp. 2606798. [DOI:10.1155/2020/2606798] [PMID] [PMCID]

Dartey, A. F., Phuma-Ngaiyaye, E. E. & Phletlhu, D. R., 2017. Effects of death as a unique experience among midwives in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. International Journal of Health and Sciences Research, 7(12), pp. 158-67. [Link]

Fetter, K. L., 2012. We grieve too: One inpatient oncology unit's interventions for recognizing and combating compassion fatigue. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16(6), 559–561.[DOI:10.1188/12.CJON.559-561] [PMID]

Fuchs, T., 2013. Depression, intercorporeality, and interaffectivity. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 20(7-8), pp. 219-38. [Link]

Gerow, L., et al., 2010. Creating a curtain of protection: Nurses’ experiences of grief following patient death. Journal of nursing scholarship, 42(2), pp. 122–9. [DOI:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01343.x] [PMID]

Given, B., et al., 2004. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end-of-life. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31(6), pp. 1105–17. [PMID] [PMCID]

Hall, C., 2011. Beyond Kübler-Ross: Recent developments in our understanding of grief and bereavement. InPsych. The Bulletin of the Australian Psychological Society Ltd, 33(6), pp. 8-11. [DOI:10.1080/02682621.2014.902610]

Higgins, D., 2009. Last offices. In P. Jevon (Ed.), Care of the dying and deceased patient: A practical guide for nurses. New York: Wiley. [Link]

Hooyman, N. R., & Kramer, B. J., 2008. Living through loss: Interventions across the life span. New York: Columbia University Press. [Link]

Jonas-Simpson, C., et al., 2013. Nurses’ experiences of grieving when there is a perinatal death. Sage Open, 3(2), pp. 1-11. [DOI:10.1177/2158244013486116]

Keene, E. A., et al., 2010. Bereavement debriefing sessions: An intervention to support health care professionals in managing their grief after the death of a patient. Pediatric Nursing, 36(4), pp. 185-9. [Link]

Kent, B., Anderson, N. E. & Owens, R. G., 2012. Nurses’ early experiences with patient death: The results of an on-line survey of Registered Nurses in New Zealand. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(10), pp. 1255–65. [PMID]

Khalaf, I. A., et al., 2018. Nurses’ experiences of grief following patient death: A qualitative approach. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 36(3), pp. 228–40. [DOI:10.1177/0898010117720341] [PMID]

Kim, J. H. & Park, E., 2012. The effect of job-stress and self-efficacy on depression of clinical nurses. Korean Journal of Occupational Health Nursing, 21(2), pp. 134-44. [DOI:10.5807/kjohn.2012.21.2.134]

Krejcie R. V., & Morgan, D. W., 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Education and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), pp. 607-10. [DOI:10.1177/001316447003000308]

Kübler-Ross, E., 1973. On death and dying. London: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9780203010495]

Lally, R. M., 2005. Oncology nurses share their experiences with bereavement and self-care. Ons News, 20(10), pp. 4-11. [PMID]

MacDermott, C. & Keenan, P. M., 2014. Grief experiences of nurses in Ireland who have cared for children with an intellectual disability who have died. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 20(12), pp. 584–90. [DOI:10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.12.584] [PMID]

Maytum, J. C., Heiman, M. B. & Garwick, A. W., 2004. Compassion fatigue and burnout in nurses who work with children with chronic conditions and their families. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 18(4), 171-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedhc.2003.12.005] [PMID]

Medland, J., Howard-Ruben, J. & Whitaker, E., (2004). Fostering psychosocial wellness in oncology nurses: Addressing burnout and social support in the workplace. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31(1), pp. 47–54. [PMID]

Meert, K. L., et al., 2011. Follow-up study of complicated grief among parents eighteen months after a child's death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 14(2), 207-214. [DOI:10.1089/jpm.2010.0291] [PMID] [PMCID]

Meller, N., et al., 2019. Grief experiences of nurses after the death of an adult patient in an acute hospital setting: An integrative review of literature. Collegian, 26(2), pp. 302-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.colegn.2018.07.011]

Moussavi, S., et al., 2007. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: Results from the World Health Surveys. The Lancet, 370(9590), pp. 851-8. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9]

Papadatou, D., 2000. A proposed model of health professionals’ grieving process. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 41(1), pp. 59-77. [DOI:10.2190/TV6M-8YNA-5DYW-3C1E]

Papadatou, D., et al., 2002. Greek nurse and physician grief as a result of caring for children dying of cancer. Pediatric Nursing, 28(4), pp. 345–53. [PMID]

Pipe, T. B. & Bortz, J. J., 2009. Mindful leadership as healing practice: Nurturing self to serve others. International Journal for Human Caring, 13(2), pp. 34-8. [DOI:10.20467/1091-5710.13.2.34]

Reid F., 2013. Grief and the experiences of nurses providing palliative care to children and young people at home. Nursing Children and Young People, 25(9), pp. 31-6. [PMID]

Shinbara, C. G. & Olson, L., 2010. When nurses grieve: Spirituality’s role in coping. Journal of Christian Nursing: A Quarterly Publication of Nurses Christian Fellowship, 27(1), pp. 32-7. [PMID]

Shorter, M. & Stayt, L. C., 2010. Critical care nurses’ experiences of grief in an adult intensive care unit. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(1), pp. 159–67. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05191.x] [PMID]

Showalter, S. E., 2010. Compassion fatigue: What is it? Why does it matter? Recognizing the symptoms, acknowledging the impact, developing the tools to prevent compassion fatigue, and strengthen the professional already suffering from the effects. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 27(4), pp. 239–42. [DOI:10.1177/1049909109354096] [PMID]

Wakefield A., 2000. Nurses’ responses to death and dying: A need for relentless self-care. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 6(5), pp. 245–51. [PMID]

Yoon, S. H., 2009. Occupational stress and depression in clinical nurses-using Korean occupational stress scales. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration, 15(3), pp. 463-70.

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2022/04/3 | Accepted: 2022/05/14 | Published: 2022/08/1

Received: 2022/04/3 | Accepted: 2022/05/14 | Published: 2022/08/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |