Tue, Jul 16, 2024

[Archive]

Volume 9, Issue 4 (Autumn 2023)

JCCNC 2023, 9(4): 309-316 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Pangandaman H. Challenges Faced by Digital Immigrant Nurse Educators in Adopting Flexible Learning Options During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Phenomenological Study. JCCNC 2023; 9 (4) :309-316

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-496-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-496-en.html

Department of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, Mindanao State University, Main Campus, Mindanao State University, Marawi, Philippines. , hamdoni.pangandaman@msumain.edu.ph

Full-Text [PDF 523 kb]

(220 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (931 Views)

Nurse educators born before 1985 may have limited knowledge and skills in technology.

• These educators, known as digital immigrants, faced challenges adopting flexible learning options (FLO) during the pandemic.

• Digital immigrant nurse educators in this study experienced 4 challenges in adopting FLO: Lack of technological knowledge and skills, difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods, inadequate technological resources, and emotional stress and exhaustion.

• These challenges hinder the adoption of FLO by digital immigrant nurse educators.

• Providing ongoing support, resources, and training can help improve technical knowledge and skills and enable the successful integration of FLO into their teaching practices.

Plain Language Summary

Digital immigrant educators often struggle with technology due to their limited exposure and unfamiliarity with its practical applications. They find adapting to new teaching methods challenging and may lack access to essential technological resources. Additionally, implementing flexible learning options during the pandemic has increased emotional stress and exhaustion for these educators. They needed support, training, and resources to improve their technological proficiency and emotional well-being, ultimately enhancing the quality of education for students.

• These educators, known as digital immigrants, faced challenges adopting flexible learning options (FLO) during the pandemic.

• Digital immigrant nurse educators in this study experienced 4 challenges in adopting FLO: Lack of technological knowledge and skills, difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods, inadequate technological resources, and emotional stress and exhaustion.

• These challenges hinder the adoption of FLO by digital immigrant nurse educators.

• Providing ongoing support, resources, and training can help improve technical knowledge and skills and enable the successful integration of FLO into their teaching practices.

Plain Language Summary

Digital immigrant educators often struggle with technology due to their limited exposure and unfamiliarity with its practical applications. They find adapting to new teaching methods challenging and may lack access to essential technological resources. Additionally, implementing flexible learning options during the pandemic has increased emotional stress and exhaustion for these educators. They needed support, training, and resources to improve their technological proficiency and emotional well-being, ultimately enhancing the quality of education for students.

Full-Text: (84 Views)

1. Introduction

Educators in higher education institutions, per the directive of the Philippines Commission on Higher Education (CHED) under memorandum order No. 05 series of 2020, are mandated to adopt flexible learning option (FLO) as a strategy to contextualize the learning process amid the COVID-19 pandemic (CHED, 2020). Flexible learning is the most feasible method to process and address distance learning among facilitators of learning and learners due to community and home quarantine imposed by the government. This strategy has been patronized by the government segment of education in countries such as the Philippines, China, Hong Kong, and Singapore to consider its feasibility during a crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic (Huang et al., 2020; Martin & Godonoga, 2020).

Among the institutions represented by digital immigrant and native workforce, the former encounters several challenges in adopting FLO as a digitally driven strategy (Kesharwani, 2020). In this regard, nurse educators affiliated with higher education institutions are expected to navigate the learning process using existing technologies to facilitate FLO (Monsivais & Robbins, 2020). Digital native educators have a distinct advantage due to their exposure to technology from an early age. This exposure enables them to adapt easily and become familiar with various technologies, making learning and applying practical applications easier (Khoshnevisan, 2020). They have strong positive beliefs, are proficient in essential technologies, and integrate them into their classes (Lei, 2009; Pangandaman, 2018).

However, the journey is challenging for digital immigrant nurse educators (born before 1985), who are on the verge of adapting and learning new things in using and integrating technology into classes. They have to embrace and integrate FLO as a new scheme of teaching and learning that disfavors their traditional methods or conventional pedagogical approaches (Gronseth et al., 2010; Wargadinata et al., 2020). There seems to be a gap between educators, new methods of learning, and learners, with digital immigrant educators on the furthest line of the gap (Monsivais & Robbins, 2020; Wargadinata et al., 2020). As described by Prensky, digital immigrants are the generations who grew up before the rise of the Internet, digital technologies, and other computing devices, which they need to adapt and learn in the present (Prensky, 2001).

The adoption of FLO in response to the limitations imposed by the pandemic highlighted a deeper understanding of the experiences and perspectives of nurse educators in higher education institutions. On the other hand, phenomenological research, as a qualitative approach, seeks to understand and describe the universal essence of a phenomenon as people experience it (Knaack, 1984). Thus, phenomenological studies could provide valuable insights into the experiences of these educators, particularly in relation to the integration of technology and the shift from traditional pedagogical approaches.

This phenomenological study seeks to explore the challenges digital immigrant nurse educators face in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. By shedding light on digital immigrant educators’ experiences encountering new teaching and learning methods, the study aims to leverage phenomenology to delve into their subjective world—exploring beliefs, attitudes, and experiences related to technology integration and FLO (Neubauer et al., 2019). By understanding digital immigrant educators’ unique challenges in adopting these new approaches, educational institutions could develop targeted support and training programs to facilitate their transition and bridge the gap between different generations of nursing educators.

2. Materials and Methods

A qualitative phenomenology research approach was adopted, involving 6 digital immigrant nurse educators as participants who reached the saturation of responses after a series of interviews and validations. The researcher strictly adheres to the theoretical saturation principles where further data collection and analysis ceased to yield significant new insights or information, indicating comprehensive coverage of the research objectives (Saunders et al., 2018). Based on purposive sampling, participants were educators born before the year 1985 or were 35 to 65 years old, having at least 10 years in the nursing institution at the College of Health Sciences of Mindanao State University, and expressing difficulty in adopting FLO as a strategy. In-depth interviews were used to gain participants’ experiences. The interviews were conducted using an open-ended guide questionnaire designed to explore the challenges digital immigrant nurse educators face in adopting FLO. The first open question posed to the participants was, “Can you please describe your experience in adopting FLO during the COVID-19 pandemic?”

The interviews were conducted through scheduled meetings using the Zoom application software, version 5.13 providing a convenient remote communication platform. The number of participants was determined based on theoretical data saturation, wherein additional interviews were not expected to yield significantly new information or insights regarding the challenges faced by digital immigrant nurse educators.

The mean duration of the interviews was approximately 45 minutes, allowing sufficient time for participants to provide detailed responses and share their perspectives on the topic. The interviews were conducted by the researcher, who possessed the necessary expertise and training in qualitative research methods and phenomenology to ensure a rigorous and in-depth exploration of the participants’ experiences and challenges.

The data generated through interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using Colaizzi’s method in 7 steps (Wirihana et al., 2018) as follows:

1. Familiarization: The researcher immersed in data gathered from the interviews conducted with 6 digital immigrant nurse educators by listening to recorded interviews and reading the transcripts. These educators met the criteria of being born before 1985 or aged 35 to 65, having at least 10 years of experience in the nursing institution at Mindanao State University, and expressing difficulty in adopting FLO as a strategy.

2. Coding: The recorded and transcribed interviews were imported into MaxQDA application software, facilitating the coding process. The researchers systematically analyzed the data by identifying significant statements, concepts, and themes related to digital immigrant nurse educators’ challenges in adopting FLO.

3. Creating categories: Through coding, the researchers organized the identified statements, concepts, and themes into meaningful categories. These categories helped researchers structure and organize the data and comprehensively understand the challenges educators face.

4. Developing themes: The researchers developed themes based on the categories derived from the coding process, representing the central ideas and patterns within the data. These themes captured the essence of the challenges experienced by digital immigrant nurse educators in adopting FLO during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Reviewing and refining themes: The researchers reviewed and refined the identified themes by continuously examining the data to accurately reflect the experiences and perspectives of the participants. This iterative process helped ensure the identified themes’ validity and reliability.

6. Seeking feedback: To enhance the trustworthiness of the findings, the researcher sought feedback from the participants. The findings were shared with some participants to validate the accuracy and relevance of the identified themes. This member-checking process ensured that the interpretations and conclusions drawn from the data were aligned with the participants’ experiences.

7. Reporting: The final step involved reporting the findings clearly and coherently. The researchers presented the identified themes, supported by relevant quotes and examples, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by digital immigrant nurse educators in adopting FLO during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data trustworthiness

The Guba and Lincoln (Nowell et al., 2017) approach was employed to establish the trustworthiness of the findings in the study. First, the author engaged with the data for approximately 7 months to enhance credibility. Data collection involved online interviews through Zoom and Facebook Messenger software applications. We used maximum variation in the sampling strategy, including participants with diverse ages, genders, levels of education, and work experiences. Member checks were implemented by sharing the findings with selected participants and soliciting their feedback. To guarantee the confirmability of the data, a peer check was conducted by two faculty members with expertise in qualitative research. Afterward, an inquiry audit was employed to ensure dependability, wherein the interviews and analyses were reviewed by an external professor not involved in the study. Lastly, a detailed description of the study context was provided to promote the transferability of the findings.

3. Results

This study explored the challenges digital immigrant nurse educators face in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy during the pandemic. Six nurse educators were interviewed, all born before 1985 and teaching in a nursing institution for at least 10 years. Based on their descriptive characteristics in Table 1, their age ranged from 47 to 58 and were predominantly female. They were MA Nursing holders, and 3 had PhD degrees with a range of experience from 17 to 25 years.

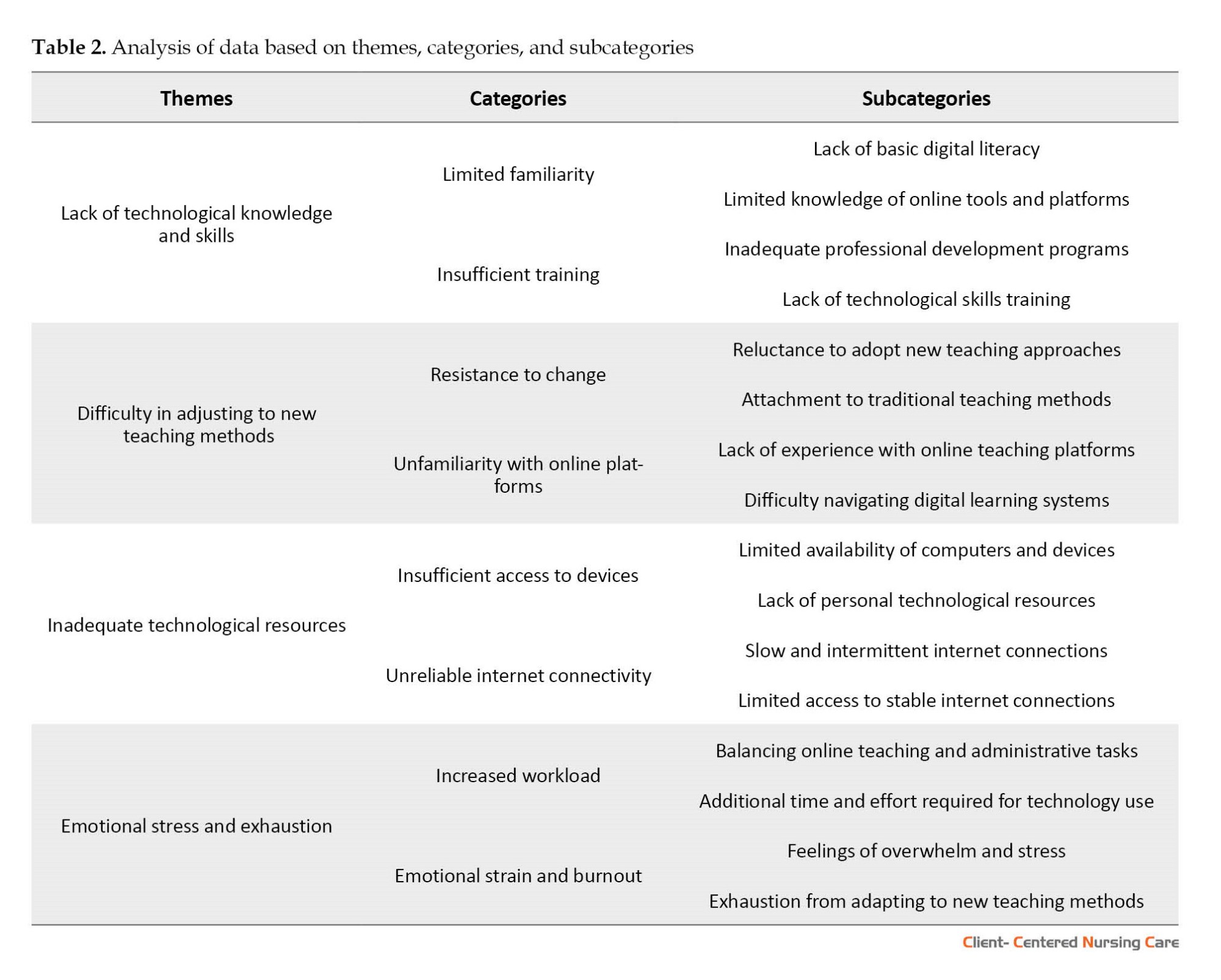

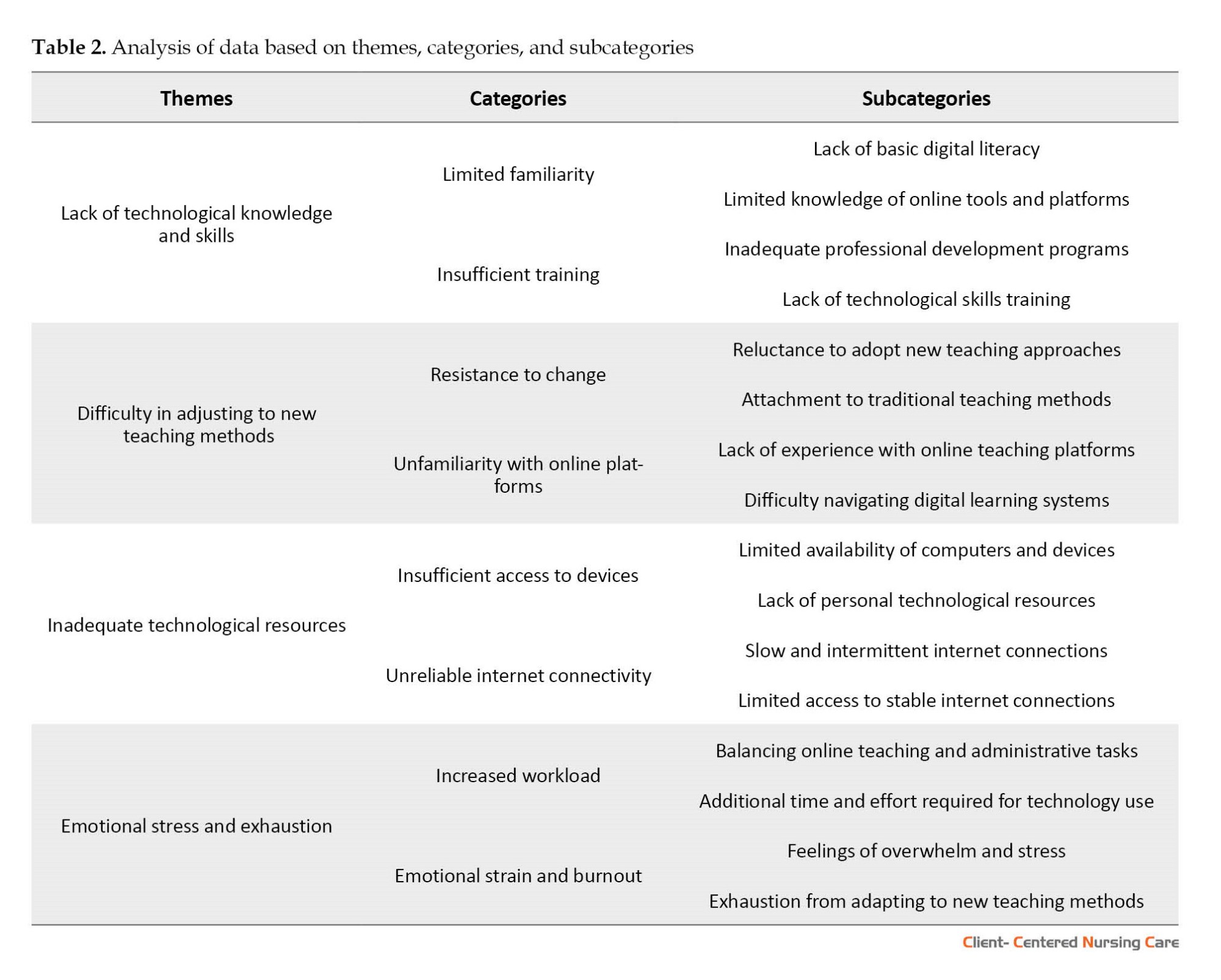

Through the qualitative phenomenology approach and Colaizzi’s method of analysis, the following 4 themes emerged: 1) Lack of technological knowledge and skills, 2) Difficulty in adjusting to new teaching methods, 3) Inadequate technological resources, and 4) Emotional stress and exhaustion. The emerged themes, categories, and subcategories are presented in Table 2.

Theme 1: Lack of technological knowledge and skills

The lack of technological knowledge and skills makes it challenging for digital immigrant nurse educators to implement FLO amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Being part of a generation not raised by technology, these educators may find it uncomfortable to use it as digital natives. They may need help to adapt to new technologies and be more familiar with their practical applications in the classroom. It is challenging for them to integrate technology into their teaching methods effectively. This condition can create a gap between educators and learners, especially digital natives, hindering the delivery of quality education through FLO. Participants expressed these challenges as follows:

“I find it challenging to implement FLO because I have limited knowledge and skills when it comes to technology. As a digital immigrant, I did not grow up with technology as part of my everyday life. I have to learn and adapt to new tools and platforms that I am not familiar with, which takes a lot of time and effort. It can be overwhelming and frustrating, especially when I have to balance teaching and learning new technological skills at the same time. It also affects my confidence as an educator, as I worry that I may not be able to effectively deliver the content to my students using these new technologies” (Participant 1).

“I find it challenging to navigate and troubleshoot technological problems during online classes, especially when limited IT (information technology) support is available. It takes up much of my time and affects my ability to effectively teach my students” (Participant 3).

“I am behind on the latest technologies and teaching strategies, which makes it difficult for me to keep up with the demands of FLO. It’s overwhelming to learn and apply new skills while also trying to manage the workload and adjust to the new normal brought about by the pandemic” (Participant 6).

Therefore, providing support and resources to digital immigrant educators to improve their technological knowledge and skills is crucial. It helps them effectively navigate the new landscape of education in the digital age.

Theme 2: Difficulty in adjusting to new teaching methods

Digital immigrant nurse educators, with a tenure of at least 10 years, may have established a routine and familiarity with traditional face-to-face teaching methods. The sudden shift to FLO amidst the pandemic demands an adjustment to new teaching methods, which can be challenging. Moreover, the lack of confidence and resistance to change can hinder their willingness to try new teaching strategies, resulting in difficulties in implementing FLO. This difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods highlights the need for continuous support and training for digital immigrant nurse educators to integrate FLO successfully in their teaching practices. Their thoughts are reflected as follows:

“I find it challenging to adjust to new teaching methods because I am used to traditional face-to-face teaching, and now I have to learn how to teach online. It requires me to restructure my course and lesson plans, which takes a lot of time and effort” (Participant 2).

“As a digital immigrant nurse educator, I find it challenging to adjust to new teaching methods because I am used to the traditional face-to-face teaching approach. It is difficult for me to shift my teaching strategies to fit the digital platform, especially since I have little to no experience in using online tools and technologies for teaching” (Participant 5).

“As a digital immigrant nurse educator, I have developed teaching strategies that have worked for me in the past. However, with the shift to FLO, I have to unlearn some of my old teaching methods and learn new ones. It can be overwhelming and time-consuming” (Participant 4).

Theme 3: Inadequate technological resources

Inadequate technological resources present a significant challenge for digital immigrant nurse educators in implementing FLO amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. This condition limits the participant’s ability to effectively use and integrate technology into their teaching methods. Digital immigrant educators may lack access to essential technological tools and infrastructure, such as reliable internet connection, computers, and other necessary software and applications. These shortcomings hinder their ability to provide quality online instruction. Moreover, the lack of support and training on effectively using these resources further exacerbates the challenge, requiring significant time and effort for educators to familiarize themselves with new technologies and pedagogies. This situation can lead to frustration and a sense of disconnection between educators and their students, potentially compromising the quality of education. Their claim on these challenges is presented in the following comments:

“We have limited access to computers and internet connection at home. Even if we have the basic knowledge and skills to use technology, we are still challenged by the lack of resources. It affects our ability to develop and deliver quality online content for our students” (Participant 3).

“As digital immigrant nurse educators, we are expected to learn and use new technology, but we don’t have the resources to purchase and use them effectively. This hinders our ability to provide quality education to our students through FLO” (Participant 4).

“The lack of technological resources also limits our creativity in developing engaging and interactive online content for our students. We are forced to rely on basic tools and platforms that may be less effective in promoting active learning and student engagement” (Participant 3).

Theme 4: Emotional stress and exhaustion

Implementing FLO amid the COVID-19 pandemic has not only required digital immigrant nurse educators to adjust to new technologies and teaching methods but has also placed additional emotional stress and exhaustion on them. These educators have had to adapt to a rapidly changing environment, learn new technologies and teaching methods, and manage additional workloads. They have also had to manage their emotional and mental well-being while supporting their students through challenging times. This combination of factors can lead to burnout, emotional exhaustion, and increased stress levels, making it challenging for them to implement FLO effectively. Participants shared their sentiments as follows:

“It’s not just complaining of the lack of technological skills and knowledge, but also the emotional stress and exhaustion we feel as educators. It’s challenging to switch to a completely different mode of teaching and learning while also worrying about the health and safety of our students, ourselves, and our families during this pandemic. We must constantly adapt to new situations and changes, which can be overwhelming and draining” (Participant 5).

“As digital immigrant nurse educators, we are not only trying to adapt to new technology and teaching methods, but we are also dealing with our personal lives and the challenges brought by the pandemic. We have to manage our emotions, take care of our families, and keep ourselves healthy while fulfilling our responsibilities as educators” (Participant 6).

“The sudden shift to FLO requires a lot of preparation and adjustments, which can be emotionally exhausting for us. We must learn new skills, redesign our teaching materials, and find ways to engage with our students remotely. All these added responsibilities can lead to burnout and affect our mental health” (Participant 1).

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a rapid shift in teaching strategies, with FLO becoming a necessary teaching method for most educators. However, digital immigrant nurse educators may face challenges in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy, which this study aimed to explore. This study found that the challenges they faced in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy were limited technological knowledge and skills, difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods, inadequate technological resources, and emotional stress and exhaustion.

The lack of technological knowledge and skills was the most challenging aspect for digital immigrant nurse educators in implementing FLO. Because digital immigrant nurse educators may struggle to adapt to new technologies and be unfamiliar with their practical applications in the classroom, integrating technology effectively into their teaching methods becomes a challenging endeavor (Gause et al., 2022; Li et al., 2019; Pangandaman et al., 2019). The lack of confidence and resistance to change can further hinder their willingness to try new teaching strategies (Wang, 2017; Haleem et al., 2022). Hence, it is crucial to provide support and resources to digital immigrant educators to improve their technological knowledge and skills.

Moreover, digital immigrant nurse educators teaching for at least 10 years may have established a routine and familiarity with traditional face-to-face teaching methods. The sudden shift to FLO requires them to adjust and learn new teaching methods, which can be challenging (Prensky, 2010; Haleem et al., 2022). This difficulty in adjusting to new teaching methods highlights the need for continuous support and training for digital immigrant nurse educators to ensure the successful integration of FLO in their teaching practices (Yildirim & Kiray, 2016; Gause et al., 2022).

Inadequate technological resources are another challenge for digital immigrant nurse educators implementing FLO. Digital immigrant educators may need access to essential technological tools and infrastructure, such as reliable internet connections, computers, and other necessary software and applications. This shortcoming hinders their ability to provide quality online instruction. The lack of support and training on effectively using these resources further compounds the challenge, as it may require significant time and effort to familiarize themselves with new technologies and pedagogies (Jarrahi & Eshraghi, 2019).

Finally, emotional stress and exhaustion are significant challenges for digital immigrant nurse educators in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy during the pandemic. The abrupt shift to FLO and the increased workload can lead to emotional exhaustion and burnout, especially for those unfamiliar with technology. Accordingly, this state can manifest in various ways, including decreased motivation, difficulty concentrating, and frustration and anxiety (Herrera Mosquera, 2017; Carrión-Martínez et al., 2021). This challenge highlights the need for emotional support and self-care strategies for digital immigrant nurse educators.

In conclusion, digital immigrant nurse educators face numerous challenges in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy during the pandemic, such as limited technical knowledge and skills, difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods, inadequate technological resources, and emotional stress and exhaustion. To overcome these challenges, continuous support, training, and resources should be provided to digital immigrant nurse educators to improve their technological knowledge, skills, and emotional well-being. These efforts can lead to better integration of FLO in their teaching practices and improved quality of education for their students.

This study recognized some limitations, including the perspective on other practices in nursing education, which may not represent the challenges faced by digital immigrant nurse educators. In addition, this qualitative research has its limitations in terms of transferability. Furthermore, the study only used interviews as a method of data collection, which may not capture the full range of challenges faced by digital immigrant nurse educators in implementing FLO. More comprehensive studies using multiple data collection methods can increase the findings’ reliability and transferability.

5. Conclusion

The study explored the challenges digital immigrant nurse educators face in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Six nurse educators were interviewed in this regard, and 4 themes emerged: Lack of technological knowledge and skills, difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods, inadequate technological resources, and emotional stress and exhaustion. Digital immigrant educators need to gain specialized knowledge and skills to ensure their ability to integrate technology effectively into their teaching methods. In contrast, difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods highlights the need for continuous support and training. Inadequate technological resources compound the challenges, limiting educators’ ability to provide quality online instruction. These challenges emphasize the need to offer digital immigrant educators support and resources to improve their technological knowledge and skills. These measures help them successfully navigate the new landscape of education in the digital age.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the MSU College of Health Sciences, Mindanao State University (Code: CHS-REC-09122021). The participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information, and written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the administration of Mindanao State University, for their support and all participants for their cooperation.

References

Carrión-Martínez, J. J., et al., 2021. Family and school relationship during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), pp. 11710. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph182111710] [PMID]

Commission on Higher Education (CHED)., 2020. Guidelines on the implementation of flexible learning. Quezon City: Commission on Higher Education (CHED). [Link]

Gause, G., Mokgaola, I. O. & Rakhudu, M. A., 2022. Technology usage for teaching and learning in nursing education: An integrative review. curationis, 45(1), pp. e1–9. [DOI:10.4102%2Fcurationis.v45i1.2261] [PMID]

Gronseth, S., et al., 2010. Equipping the next generation of teachers: Technology preparation and practice. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 27(1), pp. 30-6. [DOI:10.1080/21532974.2010.10784654]

Haleem, A., et al., 2022. Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustainable Operations and Computers, 3, pp. 275-85. [DOI:10.1016/j.susoc.2022.05.004]

Herrera Mosquera, L., 2017. Impact of implementing a virtual learning environment (VLE) in the EFL classroom. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 22(3), pp. 479-98. [DOI:10.17533/udea.ikala.v22n03a07]

Huang, R., et al., 2020. Guidance on flexible learning during campus closures: Ensuring course quality of higher education in COVID-19 outbreak. Beijing: Smart Learning Institute of Beijing Normal University. [Link]

Jarrahi, M. H., & Eshraghi, A., 2019. Digital natives vs digital immigrants: A multidimensional view on interaction with social technologies in organizations. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 32(6), pp. 1051-70. [DOI:10.1108/JEIM-04-2018-0071]

Kesharwani, A., 2020. Do (how) digital natives adopt a new technology differently than digital immigrants? A longitudinal study. Information & Management, 57(2), pp.103170. [DOI:10.1016/j.im.2019.103170]

Khoshnevisan, B., 2020. Materials development for the digital native generation: Teachers as materials developers. MWIS Newsletter-TESOL International Association, 23(1), pp. 6-10. [Link]

Knaack, P., 1984. Phenomenological research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 6(1), pp. 107-14. [DOI:10.1177/019394598400600108] [PMID]

Lei, J., 2009. Digital natives as preservice teachers: What technology preparation is needed? Journal of Computing in Teacher Education, 25(3), pp. 87-97. [Link]

Li, Y., Wang, Q. & Lei, J., 2019. Exploring different needs of digital immigrant and native teachers for technology professional development in China. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning, 15(1), pp. 32-48. [DOI:10.37120/ijttl.2019.15.1.03]

Martin, M. & Godonoga, A., 2020. SDG 4: Policies for flexible learning pathways in higher education: Taking stock of good practices internationally. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning.

Monsivais, D. B. & Robbins, L. K., 2020. Better together: Faculty development for quality improvement in the nurse educator role. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 15(1), pp. 7-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.teln.2019.08.004]

Neubauer, B. E., Witkop, C. T. & Varpio, L., 2019. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(2), pp. 90–7. [DOI:10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2] [PMID]

Nowell, L. S., et al., 2017. Thematic analysis: Striving to Meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1). [DOI:10.1177/1609406917733847]

Pangandaman, H. K., 2018. Effects of flipped classroom videos in the return demonstration performance of nursing students. Scholar Journal of Applied Sciences and Research, 1(4), pp. 55-8. [Link]

Pangandaman, H. K., et al., 2019. Philippine higher education vis-à-vis education 4.0: A scoping review. International Journal of Advanced Research and Publications, 3(3), pp. 65-9. [Link]

Prensky, M., 2001. Digital natives, digital immigrants. On The Horizon, 9(5), pp. 1-6. [DOI:10.1108/10748120110424816]

Prensky, M. R., 2010. Teaching digital natives: Partnering for real learning. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 6(2), pp. 74-6. [Link]

Saunders, B., et al., 2018. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), pp. 1893–907. [DOI:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8] [PMID]

Wang, T., 2017. Overcoming barriers to ‘flip’: Building teacher’s capacity for the adoption of flipped classroom in Hong Kong secondary schools. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 12(1), pp. 6. [DOI:10.1186/s41039-017-0047-7] [PMID]

Wargadinata, W., et al., 2020. Student’s responses on learning in the early COVID-19 pandemic. Tadris: Jurnal Keguruan dan Ilmu Tarbiyah, 5(1), pp. 141-53. [DOI:10.24042/tadris.v5i1.6153]

Wirihana, L., et al., 2018. Using Colaizzi’s method of data analysis to explore the experiences of nurse academics teaching on satellite campuses. Nurse Researcher, 25(4), pp. 30–4. [DOI:10.7748/nr.2018.e1516] [PMID]

Yildirim, F. S. & Kiray, S. A., 2016. Flipped classroom model in education. In: W. Wu, S. Alan, & M. T. Hebebci (eds), Research highlights in education and science. Konya: International Society for Research in Education and Science. [Link]

Educators in higher education institutions, per the directive of the Philippines Commission on Higher Education (CHED) under memorandum order No. 05 series of 2020, are mandated to adopt flexible learning option (FLO) as a strategy to contextualize the learning process amid the COVID-19 pandemic (CHED, 2020). Flexible learning is the most feasible method to process and address distance learning among facilitators of learning and learners due to community and home quarantine imposed by the government. This strategy has been patronized by the government segment of education in countries such as the Philippines, China, Hong Kong, and Singapore to consider its feasibility during a crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic (Huang et al., 2020; Martin & Godonoga, 2020).

Among the institutions represented by digital immigrant and native workforce, the former encounters several challenges in adopting FLO as a digitally driven strategy (Kesharwani, 2020). In this regard, nurse educators affiliated with higher education institutions are expected to navigate the learning process using existing technologies to facilitate FLO (Monsivais & Robbins, 2020). Digital native educators have a distinct advantage due to their exposure to technology from an early age. This exposure enables them to adapt easily and become familiar with various technologies, making learning and applying practical applications easier (Khoshnevisan, 2020). They have strong positive beliefs, are proficient in essential technologies, and integrate them into their classes (Lei, 2009; Pangandaman, 2018).

However, the journey is challenging for digital immigrant nurse educators (born before 1985), who are on the verge of adapting and learning new things in using and integrating technology into classes. They have to embrace and integrate FLO as a new scheme of teaching and learning that disfavors their traditional methods or conventional pedagogical approaches (Gronseth et al., 2010; Wargadinata et al., 2020). There seems to be a gap between educators, new methods of learning, and learners, with digital immigrant educators on the furthest line of the gap (Monsivais & Robbins, 2020; Wargadinata et al., 2020). As described by Prensky, digital immigrants are the generations who grew up before the rise of the Internet, digital technologies, and other computing devices, which they need to adapt and learn in the present (Prensky, 2001).

The adoption of FLO in response to the limitations imposed by the pandemic highlighted a deeper understanding of the experiences and perspectives of nurse educators in higher education institutions. On the other hand, phenomenological research, as a qualitative approach, seeks to understand and describe the universal essence of a phenomenon as people experience it (Knaack, 1984). Thus, phenomenological studies could provide valuable insights into the experiences of these educators, particularly in relation to the integration of technology and the shift from traditional pedagogical approaches.

This phenomenological study seeks to explore the challenges digital immigrant nurse educators face in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. By shedding light on digital immigrant educators’ experiences encountering new teaching and learning methods, the study aims to leverage phenomenology to delve into their subjective world—exploring beliefs, attitudes, and experiences related to technology integration and FLO (Neubauer et al., 2019). By understanding digital immigrant educators’ unique challenges in adopting these new approaches, educational institutions could develop targeted support and training programs to facilitate their transition and bridge the gap between different generations of nursing educators.

2. Materials and Methods

A qualitative phenomenology research approach was adopted, involving 6 digital immigrant nurse educators as participants who reached the saturation of responses after a series of interviews and validations. The researcher strictly adheres to the theoretical saturation principles where further data collection and analysis ceased to yield significant new insights or information, indicating comprehensive coverage of the research objectives (Saunders et al., 2018). Based on purposive sampling, participants were educators born before the year 1985 or were 35 to 65 years old, having at least 10 years in the nursing institution at the College of Health Sciences of Mindanao State University, and expressing difficulty in adopting FLO as a strategy. In-depth interviews were used to gain participants’ experiences. The interviews were conducted using an open-ended guide questionnaire designed to explore the challenges digital immigrant nurse educators face in adopting FLO. The first open question posed to the participants was, “Can you please describe your experience in adopting FLO during the COVID-19 pandemic?”

The interviews were conducted through scheduled meetings using the Zoom application software, version 5.13 providing a convenient remote communication platform. The number of participants was determined based on theoretical data saturation, wherein additional interviews were not expected to yield significantly new information or insights regarding the challenges faced by digital immigrant nurse educators.

The mean duration of the interviews was approximately 45 minutes, allowing sufficient time for participants to provide detailed responses and share their perspectives on the topic. The interviews were conducted by the researcher, who possessed the necessary expertise and training in qualitative research methods and phenomenology to ensure a rigorous and in-depth exploration of the participants’ experiences and challenges.

The data generated through interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using Colaizzi’s method in 7 steps (Wirihana et al., 2018) as follows:

1. Familiarization: The researcher immersed in data gathered from the interviews conducted with 6 digital immigrant nurse educators by listening to recorded interviews and reading the transcripts. These educators met the criteria of being born before 1985 or aged 35 to 65, having at least 10 years of experience in the nursing institution at Mindanao State University, and expressing difficulty in adopting FLO as a strategy.

2. Coding: The recorded and transcribed interviews were imported into MaxQDA application software, facilitating the coding process. The researchers systematically analyzed the data by identifying significant statements, concepts, and themes related to digital immigrant nurse educators’ challenges in adopting FLO.

3. Creating categories: Through coding, the researchers organized the identified statements, concepts, and themes into meaningful categories. These categories helped researchers structure and organize the data and comprehensively understand the challenges educators face.

4. Developing themes: The researchers developed themes based on the categories derived from the coding process, representing the central ideas and patterns within the data. These themes captured the essence of the challenges experienced by digital immigrant nurse educators in adopting FLO during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Reviewing and refining themes: The researchers reviewed and refined the identified themes by continuously examining the data to accurately reflect the experiences and perspectives of the participants. This iterative process helped ensure the identified themes’ validity and reliability.

6. Seeking feedback: To enhance the trustworthiness of the findings, the researcher sought feedback from the participants. The findings were shared with some participants to validate the accuracy and relevance of the identified themes. This member-checking process ensured that the interpretations and conclusions drawn from the data were aligned with the participants’ experiences.

7. Reporting: The final step involved reporting the findings clearly and coherently. The researchers presented the identified themes, supported by relevant quotes and examples, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by digital immigrant nurse educators in adopting FLO during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data trustworthiness

The Guba and Lincoln (Nowell et al., 2017) approach was employed to establish the trustworthiness of the findings in the study. First, the author engaged with the data for approximately 7 months to enhance credibility. Data collection involved online interviews through Zoom and Facebook Messenger software applications. We used maximum variation in the sampling strategy, including participants with diverse ages, genders, levels of education, and work experiences. Member checks were implemented by sharing the findings with selected participants and soliciting their feedback. To guarantee the confirmability of the data, a peer check was conducted by two faculty members with expertise in qualitative research. Afterward, an inquiry audit was employed to ensure dependability, wherein the interviews and analyses were reviewed by an external professor not involved in the study. Lastly, a detailed description of the study context was provided to promote the transferability of the findings.

3. Results

This study explored the challenges digital immigrant nurse educators face in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy during the pandemic. Six nurse educators were interviewed, all born before 1985 and teaching in a nursing institution for at least 10 years. Based on their descriptive characteristics in Table 1, their age ranged from 47 to 58 and were predominantly female. They were MA Nursing holders, and 3 had PhD degrees with a range of experience from 17 to 25 years.

Through the qualitative phenomenology approach and Colaizzi’s method of analysis, the following 4 themes emerged: 1) Lack of technological knowledge and skills, 2) Difficulty in adjusting to new teaching methods, 3) Inadequate technological resources, and 4) Emotional stress and exhaustion. The emerged themes, categories, and subcategories are presented in Table 2.

Theme 1: Lack of technological knowledge and skills

The lack of technological knowledge and skills makes it challenging for digital immigrant nurse educators to implement FLO amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Being part of a generation not raised by technology, these educators may find it uncomfortable to use it as digital natives. They may need help to adapt to new technologies and be more familiar with their practical applications in the classroom. It is challenging for them to integrate technology into their teaching methods effectively. This condition can create a gap between educators and learners, especially digital natives, hindering the delivery of quality education through FLO. Participants expressed these challenges as follows:

“I find it challenging to implement FLO because I have limited knowledge and skills when it comes to technology. As a digital immigrant, I did not grow up with technology as part of my everyday life. I have to learn and adapt to new tools and platforms that I am not familiar with, which takes a lot of time and effort. It can be overwhelming and frustrating, especially when I have to balance teaching and learning new technological skills at the same time. It also affects my confidence as an educator, as I worry that I may not be able to effectively deliver the content to my students using these new technologies” (Participant 1).

“I find it challenging to navigate and troubleshoot technological problems during online classes, especially when limited IT (information technology) support is available. It takes up much of my time and affects my ability to effectively teach my students” (Participant 3).

“I am behind on the latest technologies and teaching strategies, which makes it difficult for me to keep up with the demands of FLO. It’s overwhelming to learn and apply new skills while also trying to manage the workload and adjust to the new normal brought about by the pandemic” (Participant 6).

Therefore, providing support and resources to digital immigrant educators to improve their technological knowledge and skills is crucial. It helps them effectively navigate the new landscape of education in the digital age.

Theme 2: Difficulty in adjusting to new teaching methods

Digital immigrant nurse educators, with a tenure of at least 10 years, may have established a routine and familiarity with traditional face-to-face teaching methods. The sudden shift to FLO amidst the pandemic demands an adjustment to new teaching methods, which can be challenging. Moreover, the lack of confidence and resistance to change can hinder their willingness to try new teaching strategies, resulting in difficulties in implementing FLO. This difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods highlights the need for continuous support and training for digital immigrant nurse educators to integrate FLO successfully in their teaching practices. Their thoughts are reflected as follows:

“I find it challenging to adjust to new teaching methods because I am used to traditional face-to-face teaching, and now I have to learn how to teach online. It requires me to restructure my course and lesson plans, which takes a lot of time and effort” (Participant 2).

“As a digital immigrant nurse educator, I find it challenging to adjust to new teaching methods because I am used to the traditional face-to-face teaching approach. It is difficult for me to shift my teaching strategies to fit the digital platform, especially since I have little to no experience in using online tools and technologies for teaching” (Participant 5).

“As a digital immigrant nurse educator, I have developed teaching strategies that have worked for me in the past. However, with the shift to FLO, I have to unlearn some of my old teaching methods and learn new ones. It can be overwhelming and time-consuming” (Participant 4).

Theme 3: Inadequate technological resources

Inadequate technological resources present a significant challenge for digital immigrant nurse educators in implementing FLO amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. This condition limits the participant’s ability to effectively use and integrate technology into their teaching methods. Digital immigrant educators may lack access to essential technological tools and infrastructure, such as reliable internet connection, computers, and other necessary software and applications. These shortcomings hinder their ability to provide quality online instruction. Moreover, the lack of support and training on effectively using these resources further exacerbates the challenge, requiring significant time and effort for educators to familiarize themselves with new technologies and pedagogies. This situation can lead to frustration and a sense of disconnection between educators and their students, potentially compromising the quality of education. Their claim on these challenges is presented in the following comments:

“We have limited access to computers and internet connection at home. Even if we have the basic knowledge and skills to use technology, we are still challenged by the lack of resources. It affects our ability to develop and deliver quality online content for our students” (Participant 3).

“As digital immigrant nurse educators, we are expected to learn and use new technology, but we don’t have the resources to purchase and use them effectively. This hinders our ability to provide quality education to our students through FLO” (Participant 4).

“The lack of technological resources also limits our creativity in developing engaging and interactive online content for our students. We are forced to rely on basic tools and platforms that may be less effective in promoting active learning and student engagement” (Participant 3).

Theme 4: Emotional stress and exhaustion

Implementing FLO amid the COVID-19 pandemic has not only required digital immigrant nurse educators to adjust to new technologies and teaching methods but has also placed additional emotional stress and exhaustion on them. These educators have had to adapt to a rapidly changing environment, learn new technologies and teaching methods, and manage additional workloads. They have also had to manage their emotional and mental well-being while supporting their students through challenging times. This combination of factors can lead to burnout, emotional exhaustion, and increased stress levels, making it challenging for them to implement FLO effectively. Participants shared their sentiments as follows:

“It’s not just complaining of the lack of technological skills and knowledge, but also the emotional stress and exhaustion we feel as educators. It’s challenging to switch to a completely different mode of teaching and learning while also worrying about the health and safety of our students, ourselves, and our families during this pandemic. We must constantly adapt to new situations and changes, which can be overwhelming and draining” (Participant 5).

“As digital immigrant nurse educators, we are not only trying to adapt to new technology and teaching methods, but we are also dealing with our personal lives and the challenges brought by the pandemic. We have to manage our emotions, take care of our families, and keep ourselves healthy while fulfilling our responsibilities as educators” (Participant 6).

“The sudden shift to FLO requires a lot of preparation and adjustments, which can be emotionally exhausting for us. We must learn new skills, redesign our teaching materials, and find ways to engage with our students remotely. All these added responsibilities can lead to burnout and affect our mental health” (Participant 1).

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a rapid shift in teaching strategies, with FLO becoming a necessary teaching method for most educators. However, digital immigrant nurse educators may face challenges in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy, which this study aimed to explore. This study found that the challenges they faced in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy were limited technological knowledge and skills, difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods, inadequate technological resources, and emotional stress and exhaustion.

The lack of technological knowledge and skills was the most challenging aspect for digital immigrant nurse educators in implementing FLO. Because digital immigrant nurse educators may struggle to adapt to new technologies and be unfamiliar with their practical applications in the classroom, integrating technology effectively into their teaching methods becomes a challenging endeavor (Gause et al., 2022; Li et al., 2019; Pangandaman et al., 2019). The lack of confidence and resistance to change can further hinder their willingness to try new teaching strategies (Wang, 2017; Haleem et al., 2022). Hence, it is crucial to provide support and resources to digital immigrant educators to improve their technological knowledge and skills.

Moreover, digital immigrant nurse educators teaching for at least 10 years may have established a routine and familiarity with traditional face-to-face teaching methods. The sudden shift to FLO requires them to adjust and learn new teaching methods, which can be challenging (Prensky, 2010; Haleem et al., 2022). This difficulty in adjusting to new teaching methods highlights the need for continuous support and training for digital immigrant nurse educators to ensure the successful integration of FLO in their teaching practices (Yildirim & Kiray, 2016; Gause et al., 2022).

Inadequate technological resources are another challenge for digital immigrant nurse educators implementing FLO. Digital immigrant educators may need access to essential technological tools and infrastructure, such as reliable internet connections, computers, and other necessary software and applications. This shortcoming hinders their ability to provide quality online instruction. The lack of support and training on effectively using these resources further compounds the challenge, as it may require significant time and effort to familiarize themselves with new technologies and pedagogies (Jarrahi & Eshraghi, 2019).

Finally, emotional stress and exhaustion are significant challenges for digital immigrant nurse educators in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy during the pandemic. The abrupt shift to FLO and the increased workload can lead to emotional exhaustion and burnout, especially for those unfamiliar with technology. Accordingly, this state can manifest in various ways, including decreased motivation, difficulty concentrating, and frustration and anxiety (Herrera Mosquera, 2017; Carrión-Martínez et al., 2021). This challenge highlights the need for emotional support and self-care strategies for digital immigrant nurse educators.

In conclusion, digital immigrant nurse educators face numerous challenges in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy during the pandemic, such as limited technical knowledge and skills, difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods, inadequate technological resources, and emotional stress and exhaustion. To overcome these challenges, continuous support, training, and resources should be provided to digital immigrant nurse educators to improve their technological knowledge, skills, and emotional well-being. These efforts can lead to better integration of FLO in their teaching practices and improved quality of education for their students.

This study recognized some limitations, including the perspective on other practices in nursing education, which may not represent the challenges faced by digital immigrant nurse educators. In addition, this qualitative research has its limitations in terms of transferability. Furthermore, the study only used interviews as a method of data collection, which may not capture the full range of challenges faced by digital immigrant nurse educators in implementing FLO. More comprehensive studies using multiple data collection methods can increase the findings’ reliability and transferability.

5. Conclusion

The study explored the challenges digital immigrant nurse educators face in adopting FLO as a teaching strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Six nurse educators were interviewed in this regard, and 4 themes emerged: Lack of technological knowledge and skills, difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods, inadequate technological resources, and emotional stress and exhaustion. Digital immigrant educators need to gain specialized knowledge and skills to ensure their ability to integrate technology effectively into their teaching methods. In contrast, difficulty adjusting to new teaching methods highlights the need for continuous support and training. Inadequate technological resources compound the challenges, limiting educators’ ability to provide quality online instruction. These challenges emphasize the need to offer digital immigrant educators support and resources to improve their technological knowledge and skills. These measures help them successfully navigate the new landscape of education in the digital age.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the MSU College of Health Sciences, Mindanao State University (Code: CHS-REC-09122021). The participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information, and written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the administration of Mindanao State University, for their support and all participants for their cooperation.

References

Carrión-Martínez, J. J., et al., 2021. Family and school relationship during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), pp. 11710. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph182111710] [PMID]

Commission on Higher Education (CHED)., 2020. Guidelines on the implementation of flexible learning. Quezon City: Commission on Higher Education (CHED). [Link]

Gause, G., Mokgaola, I. O. & Rakhudu, M. A., 2022. Technology usage for teaching and learning in nursing education: An integrative review. curationis, 45(1), pp. e1–9. [DOI:10.4102%2Fcurationis.v45i1.2261] [PMID]

Gronseth, S., et al., 2010. Equipping the next generation of teachers: Technology preparation and practice. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 27(1), pp. 30-6. [DOI:10.1080/21532974.2010.10784654]

Haleem, A., et al., 2022. Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustainable Operations and Computers, 3, pp. 275-85. [DOI:10.1016/j.susoc.2022.05.004]

Herrera Mosquera, L., 2017. Impact of implementing a virtual learning environment (VLE) in the EFL classroom. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 22(3), pp. 479-98. [DOI:10.17533/udea.ikala.v22n03a07]

Huang, R., et al., 2020. Guidance on flexible learning during campus closures: Ensuring course quality of higher education in COVID-19 outbreak. Beijing: Smart Learning Institute of Beijing Normal University. [Link]

Jarrahi, M. H., & Eshraghi, A., 2019. Digital natives vs digital immigrants: A multidimensional view on interaction with social technologies in organizations. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 32(6), pp. 1051-70. [DOI:10.1108/JEIM-04-2018-0071]

Kesharwani, A., 2020. Do (how) digital natives adopt a new technology differently than digital immigrants? A longitudinal study. Information & Management, 57(2), pp.103170. [DOI:10.1016/j.im.2019.103170]

Khoshnevisan, B., 2020. Materials development for the digital native generation: Teachers as materials developers. MWIS Newsletter-TESOL International Association, 23(1), pp. 6-10. [Link]

Knaack, P., 1984. Phenomenological research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 6(1), pp. 107-14. [DOI:10.1177/019394598400600108] [PMID]

Lei, J., 2009. Digital natives as preservice teachers: What technology preparation is needed? Journal of Computing in Teacher Education, 25(3), pp. 87-97. [Link]

Li, Y., Wang, Q. & Lei, J., 2019. Exploring different needs of digital immigrant and native teachers for technology professional development in China. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning, 15(1), pp. 32-48. [DOI:10.37120/ijttl.2019.15.1.03]

Martin, M. & Godonoga, A., 2020. SDG 4: Policies for flexible learning pathways in higher education: Taking stock of good practices internationally. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning.

Monsivais, D. B. & Robbins, L. K., 2020. Better together: Faculty development for quality improvement in the nurse educator role. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 15(1), pp. 7-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.teln.2019.08.004]

Neubauer, B. E., Witkop, C. T. & Varpio, L., 2019. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(2), pp. 90–7. [DOI:10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2] [PMID]

Nowell, L. S., et al., 2017. Thematic analysis: Striving to Meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1). [DOI:10.1177/1609406917733847]

Pangandaman, H. K., 2018. Effects of flipped classroom videos in the return demonstration performance of nursing students. Scholar Journal of Applied Sciences and Research, 1(4), pp. 55-8. [Link]

Pangandaman, H. K., et al., 2019. Philippine higher education vis-à-vis education 4.0: A scoping review. International Journal of Advanced Research and Publications, 3(3), pp. 65-9. [Link]

Prensky, M., 2001. Digital natives, digital immigrants. On The Horizon, 9(5), pp. 1-6. [DOI:10.1108/10748120110424816]

Prensky, M. R., 2010. Teaching digital natives: Partnering for real learning. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 6(2), pp. 74-6. [Link]

Saunders, B., et al., 2018. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), pp. 1893–907. [DOI:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8] [PMID]

Wang, T., 2017. Overcoming barriers to ‘flip’: Building teacher’s capacity for the adoption of flipped classroom in Hong Kong secondary schools. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 12(1), pp. 6. [DOI:10.1186/s41039-017-0047-7] [PMID]

Wargadinata, W., et al., 2020. Student’s responses on learning in the early COVID-19 pandemic. Tadris: Jurnal Keguruan dan Ilmu Tarbiyah, 5(1), pp. 141-53. [DOI:10.24042/tadris.v5i1.6153]

Wirihana, L., et al., 2018. Using Colaizzi’s method of data analysis to explore the experiences of nurse academics teaching on satellite campuses. Nurse Researcher, 25(4), pp. 30–4. [DOI:10.7748/nr.2018.e1516] [PMID]

Yildirim, F. S. & Kiray, S. A., 2016. Flipped classroom model in education. In: W. Wu, S. Alan, & M. T. Hebebci (eds), Research highlights in education and science. Konya: International Society for Research in Education and Science. [Link]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2023/06/3 | Accepted: 2023/11/10 | Published: 2023/11/1

Received: 2023/06/3 | Accepted: 2023/11/10 | Published: 2023/11/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |