Mon, Feb 16, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 10, Issue 3 (Summer 2024)

JCCNC 2024, 10(3): 211-222 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Fagbenro D A, Olugbenga Olasupo M, Sunday Idemudia E, Sulaiman S A. Mediating Effect of Self-efficacy Between Personality Traits and Workplace Bullying of Nurses. JCCNC 2024; 10 (3) :211-222

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-556-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-556-en.html

Dare Azeez Fagbenro *1

, Mathew Olugbenga Olasupo2

, Mathew Olugbenga Olasupo2

, Erhabor Sunday Idemudia3

, Erhabor Sunday Idemudia3

, Sikirulai Alausa Sulaiman4

, Sikirulai Alausa Sulaiman4

, Mathew Olugbenga Olasupo2

, Mathew Olugbenga Olasupo2

, Erhabor Sunday Idemudia3

, Erhabor Sunday Idemudia3

, Sikirulai Alausa Sulaiman4

, Sikirulai Alausa Sulaiman4

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria. , fagbenro.da@unilorin.edu.ng

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences,Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

3- Social Science Cluster Faculty of Humanities, North-west University, Potchefstroom, South Africa.

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Federal University of Oye, Oye-Ekiti, Nigeria.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences,Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

3- Social Science Cluster Faculty of Humanities, North-west University, Potchefstroom, South Africa.

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Federal University of Oye, Oye-Ekiti, Nigeria.

Full-Text [PDF 872 kb]

(649 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2140 Views)

Full-Text: (763 Views)

Introduction

Workplace bullying, especially in the nursing profession, is a serious, persistent and devastating social problem that has continued to generate immense research attention among concerned health stakeholders in the world and a developing economy like Nigeria (Johnston et al., 2010; Nwaneri et al., 2017; Homayuni et al., 2021). Bullying is a work stressor that disrupts nurses’ healthy workplace environment and has a seriously deleterious effect on their well-being and performance (Munir et al., 2020; Homayuni et al., 2021). Workplace bullying refers to repetitive and constant negative behaviors directed toward an employee or their work, leading to low dignity and self-worth (Haq et al., 2018). This illicit behavior may result from work-related or personal issues, mainly by workers, supervisors, or colleagues (Einarsen, 2000; Namie & Namie, 2009). The typical workplace bullying among nurses includes non-verbal aspersion, verbal abuse, hidden information, withdrawing effort, disrupting, breaching, gloating, backbiting and broken trust (Salin, 2015). Worldwide, 39.7% of nurses have been victims of workplace bullying (Johnson, 2021) and in Nigeria, little has been documented on nurses’ bullying. Afolaranmi et al. (2022) reported that 59.7% of Nigerian health workers, including nurses, reported bullying with derogatory remarks as one serious form of bullying. Recently, Omole (2023) reported a high rate of bullying behaviors among nurses in Nigeria, with intimidation, malicious rumors, and unfair treatment as the most common forms of bullying experienced by nurses. Studies have shown that nurses who are bullied are likely to encounter different problems, such as headaches, hypertension, fatigue, insomnia, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, irritability, depression, psychological distress and burnout (Pai & Lee 2011; Rodwell et al., 2013). These problems have consequences for increased clinical errors on the part of nurses, reduced quality of patient care, absenteeism, and intention to quit their jobs (Trépanier et al., 2016). It, therefore, becomes relevant and important to offer preventive measures to eradicate this unacceptable behavior from the nursing profession.

Worldwide, many personal and organizational factors, such as organizational justice (Mohammed et al., 2018), psychological and sociodemographic factors (Akanni et al., 2020), job demands (Mokhtar et al., 2021), negative affect, role conflict and core self-evaluations (Homayuni et al., 2021) have been antecedents to workplace bullying. Most studies mentioned above have yielded inconclusive results, with most done in the Western world. The literature has relatively limited investigation of personality traits and workplace bullying among Nigerian nurses. The mechanism underlying the link between personality traits and workplace bullying through self-efficacy is also scarce in the extant literature.

According to Sadock (2003), personality is the distinct pattern of ideas, emotions, and behaviors that lasts over time and in various contexts. The broad traits constitute a complete individual’s personality and are labeled as extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience (Bolger & Zuckerman 1995), known as the big five personality traits. Extraversion is seen in activities that intensify energy as a necessary ingredient for motivation, sought from outside or external cues (Paunonen & Ashton, 2001). According to Tobin et al. (2010), agreeableness is a quality most commonly associated with interpersonal relationships and describes the types of interactions an individual prefers. According to De Raad (2000), conscientiousness is the drive to accomplish something, exemplified by thinking, self-control, and goal-oriented behavior. Neuroticism or emotional stability refers to frequent levels of emotional regulation and instability (Costa & McCrae 1992). Alarcon et al. (2009) stated that “being open to experience” was actively seeking and enjoying new experiences. There has been abundant research on personality traits and workplace bullying behavior. For instance, Jang et al. (2023) found that personality traits predicted workplace bullying among nurses in South Korea. John et al. (2021) also found that the big five personality characteristics, specifically neuroticism, play a vital role in victimization from workplace bullying. Olapegba et al. (2020) found that neuroticism trait predicted workplace bullying among 368 university staff. In their study, Rai and Agarwal (2019) found that conscientiousness, agreeableness, extraversion and openness to experience negatively correlate with workplace bullying. Halim et al. (2018) also determined that only conscientiousness influenced workplace bullying among 340 registered nurses. Also, Nielsen and Knardahl (2015) found a relationship between extraversion and workplace bullying. Munir et al. (2021) found a significant influence of agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experiences of workplace bullying. Ojedokun et al. (2014) also found that personality traits significantly affected workplace bullying. Studies in the literature have also found an association between agreeableness and bullying incidence (Seigne et al., 2007), an inverse association between agreeableness and bullying incidence, and a link between neuroticism and bullying incidence (Turner & Ireland, 2010). Despite their significance, they yielded different and conflicting results. Therefore, scholars and researchers have advocated for more empirical investigation into the precursors of workplace bullying (Coyne et al., 2000; Glasø et al., 2007; Nielsen and Knardahl, 2015). In a bid to address this call, the present study examines the direct role of personality traits and the indirect role of self-efficacy in workplace bullying, especially among nurses in a developing country like Nigeria, where bullying among nurses is a serious challenge (Omole, 2023).

Self-efficacy is a variable that may act as a possible mechanism in the relationship between personality traits and workplace bullying. Bandura (1999) defined self-efficacy as an individual belief in successfully executing and accomplishing a task in a particular situation. Higher levels of self-efficacy make a person feel more capable of meeting challenges head-on and overcoming setbacks; as a result, they are more confident in their capacity to finish a challenging activity (Bandura 1982). Self-efficacy is often considered a resource that helps ameliorate stressors at work. Therefore, self-efficacy may act as a protective buffer against workplace bullying for nurses with different traits. In incidences of bullying, personal perceptions of self-efficacy reduce the tendency to engage in negative emotions like stress, anxiety, and depression (Bandura, 1977). Additionally, higher self-efficacy may increase an individual’s self-confidence so they do not become the target of bullying and specifically protect nurses’ personalities from bullying at work. In this regard, the importance of this study lies in examining whether self-efficacy, as a useful protective factor, may help ease workplace bullying for Nigerian nurses with different personality traits.

Studies on the relationship between self-efficacy and workplace bullying are scarce and those who have looked at it have found inconclusive results, with none among nurses in Nigeria. For instance, Li et al. (2020) discovered an inverse association between self-esteem and the likelihood of reporting oneself as a victim of workplace bullying. Similarly, Bukhari et al. (2022) found an inverse relationship between workplace bullying and teacher self-efficacy. Kwiatosz-Muc et al. (2021) discovered that self-efficacy was positively related to conscientiousness, extraversion and openness to experience. Yao et al. (2018) found a connection between self-efficacy, extraversion, and neuroticism traits. In addition, Yu-hui et al. (2019) found that self-efficacy mediated the relationship between bullying and mental health and intention to leave. Also, Fang et al. (2021) found that social support mediated the relationship between workplace bullying and health problems. However, the extant literature has not investigated the indirect effect of self-efficacy in the relationship between personality traits and workplace bullying. We, therefore, presume that self-efficacy could mediate the association between personality traits and workplace bullying of Nigerian nurses.

Theoretically, we draw on social cognitive theory to examine the connections between personality traits, self-efficacy, and workplace bullying. According to the theory, those with high self-efficacy perceive difficult situations as challenges rather than threats. Conversely, those with self-doubt avoid challenging circumstances because they perceive them as dangers to their safety (Bandura, 1994). This means that nurses with high self-efficacy do not see bullying as a serious threat or challenge; instead, they believe they can cope with any adverse effect of the bullying incident. On the other hand, nurses with low self-efficacy see workplace bullying as a serious threat that they need to avoid; the inability to prevent the situation makes them experience negative emotions in the form of stress, anxiety, and depression, which, in the long run, affect their mental wellbeing.

This study aims to examine the predictive role of personality traits on workplace bullying, the role of personality traits in self-efficacy, the role of self-efficacy in workplace bullying, and the indirect role of self-efficacy in the relationship between personality and workplace bullying among nurses. The study’s results are expected to help healthcare professionals put up intervention programs that can help eradicate or minimize workplace bullying among nurses. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model and hypotheses of the study.

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedures

The study adopted a descriptive, cross-sectional design and was conducted at the University College Hospital (UCH) in Ibadan, Nigeria, in 2022. This hospital is one of the largest federal government-owned hospitals in Nigeria. According to Hair et al. (2017) recommendation, the sample size was estimated at 10 participants for each parameter. However, adding more participants increases the adequacy of the data to test the model. Therefore, this study utilized a sample size of 400. The inclusion criteria included full-time health workers in this hospital who consented to voluntary study participation. The head of the nursing unit of the UCH helped distribute the questionnaires to the nurses after the participants agreed to participate in the study. The data collection was assisted by two research assistants who distributed and recollected the questionnaires from the participants. Most questionnaires were filled out after working hours, and participants took approximately 15 minutes to complete the questionnaire. The whole exercise was completed in two weeks. Out of the 400 questionnaires administered, only 371 were filled out correctly, showing a response rate of 93%. The age range of these participants is 20–58 years old, with a Mean±SD age of 39.12±8.31 years. Their sex revealed that 66(23.7%) were males and 305(76.3%) were females. Respondents’ marital status showed that 81(21.8%) were single, 273(73.6%) married, 9(2.4%) widowed, 7(1.9%) separated and 1(.3%) divorced.

Measuring tools

Workplace bullying was assessed using the 22-item negative acts questionnaire-revised developed by Einarsen et al. (2009). This scale was used to draw individuals who have been bullied. It has three dimensions: work-related bullying, person-related bullying, and physically intimidating bullying. It is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=never to 5=always. A sample of the items follows: “I am being exposed to an unmanageable workload.” Higher scores on the scale translate to having been bullied and vice versa. The developers have reported a reliability of 0.90. In the current study, the Cronbach α of the scale was calculated as 0.92.

Personality traits were measured using the 10-item personality scale of big five inventory (BFI-10) developed by Rammstedt and John (2007). The scale has five dimensions: Extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience. Items 1R and 5 measured the dimension of extraversion, items 2 and 7R measured the dimension of agreeableness, and items 3R and 8 measured the conscientiousness dimension. Items 4R and 9 measure the domain of neuroticism, while items 5R and 10 measure the domain of openness to experience. ‘R’ means that items are reversed-scored. The scale used a response format of a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=disagree strongly, 2=disagree a little, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=agree a little and 5=agree strongly. A sample of the items on the scale is as follows, “I see myself as someone who tends to find fault with others.”

High scores on the traits mean high traits, while low scores on any of these traits indicate low traits. The authors of the scale reported a Cronbach α for the overall BFI-10 scale as 0.83, calculated as 0.71 for the whole scale in the present study.

The 10-item generalized self-efficacy scale (GSES) developed by Schwarzer and Jerusalem (1995) captured self-efficacy information on participants’ ability to engage in a task confidently. A sample item on the scale is as follows, “No matter what comes my way, I am usually able to handle it.” The response format ranges from 1=not at all true, 2=barely true, 3=moderately true, to 4=precisely true. The scores for each of the ten items are summed to give a total score; thus, the higher the score, the greater the individual generalized sense of self-efficacy. As reported by the author, the scale’s reliability ranges from 0.82 to 0.93 when examining diverse groups. In this study, a Cronbach α of 0.90 was reported.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics such as Mean±SD, and percentages were used to analyze the sociodemographic variables. The study’s hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM) and maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) with bootstrapping technique. The assumptions required regarding using SEM were met and the sample size, as recommended for SEM analysis, was above 200 (Kline 2010). Also, the Skewness and Kurtosis scores for the study data range from -0.90 to 2.30, within the range specified by Tabachnick and Fidell’s (2019) acceptable range of +2 and -2. The multicollinearity assumption was also ascertained using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance values. In this study, there was no multicollinearity issue as the tolerance value of the independent variables ranges between 0.54 and 0.82, which is within the stipulated threshold of >0.1. Also, VIF ranges from 1.20 to 1.83, within the range of <0.10 (Kline 2010). In line with Kline (2010), model fit was evaluated using the goodness of fit index (GFI, cut-off point ≥0.95), comparative fit index (CFI, cut-off point ≥0.90), normed fit index (NFI, cut-off point ≥0.90), Tucker Lewis index (TLI, cut-off point ≥0.90) and root mean square error of the approximation (RMSEA, cut-off point ≤0.07). SPSS software, version 23 were used to analyze the study data. The following hypotheses were tested:

1) Personality traits significantly predict workplace bullying; 2) Self-efficacy significantly predicts workplace bullying; 3) Self-efficacy significantly mediates the relationship between personality traits and workplace bullying.

Results

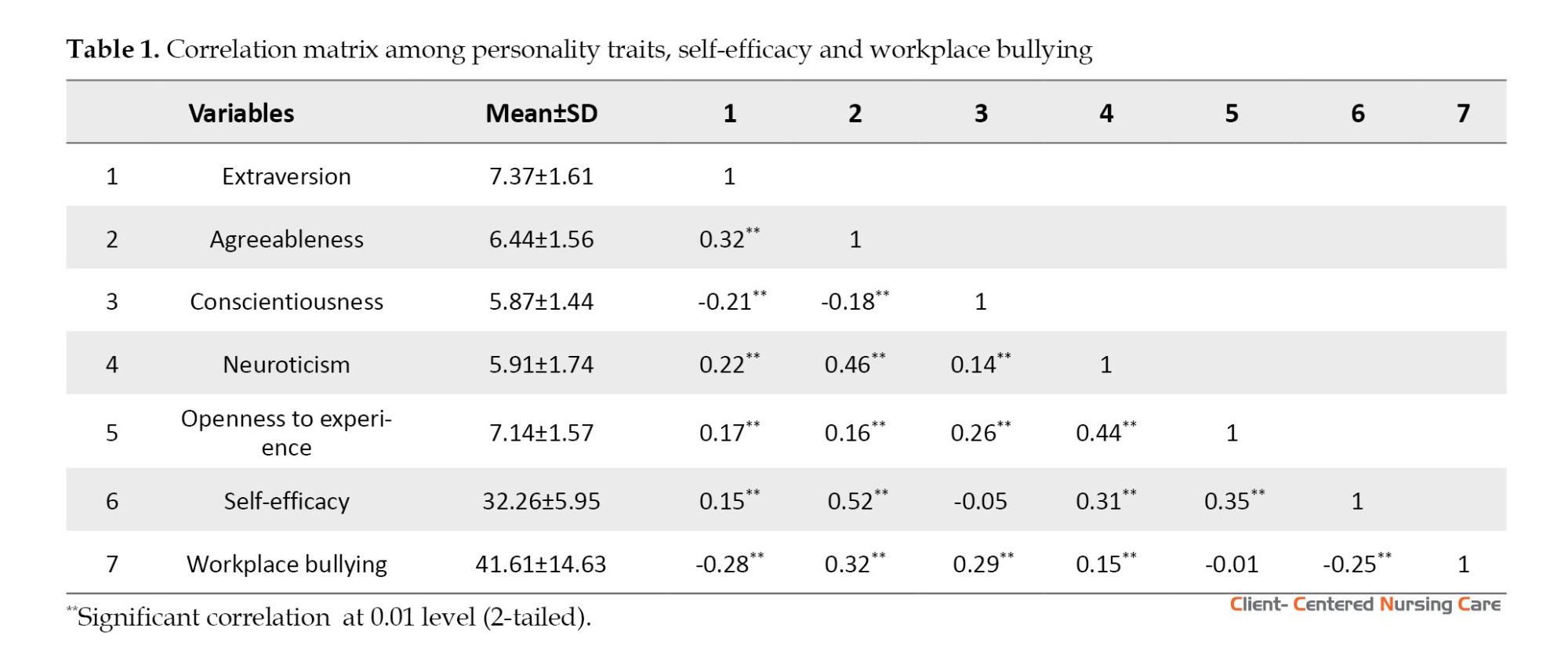

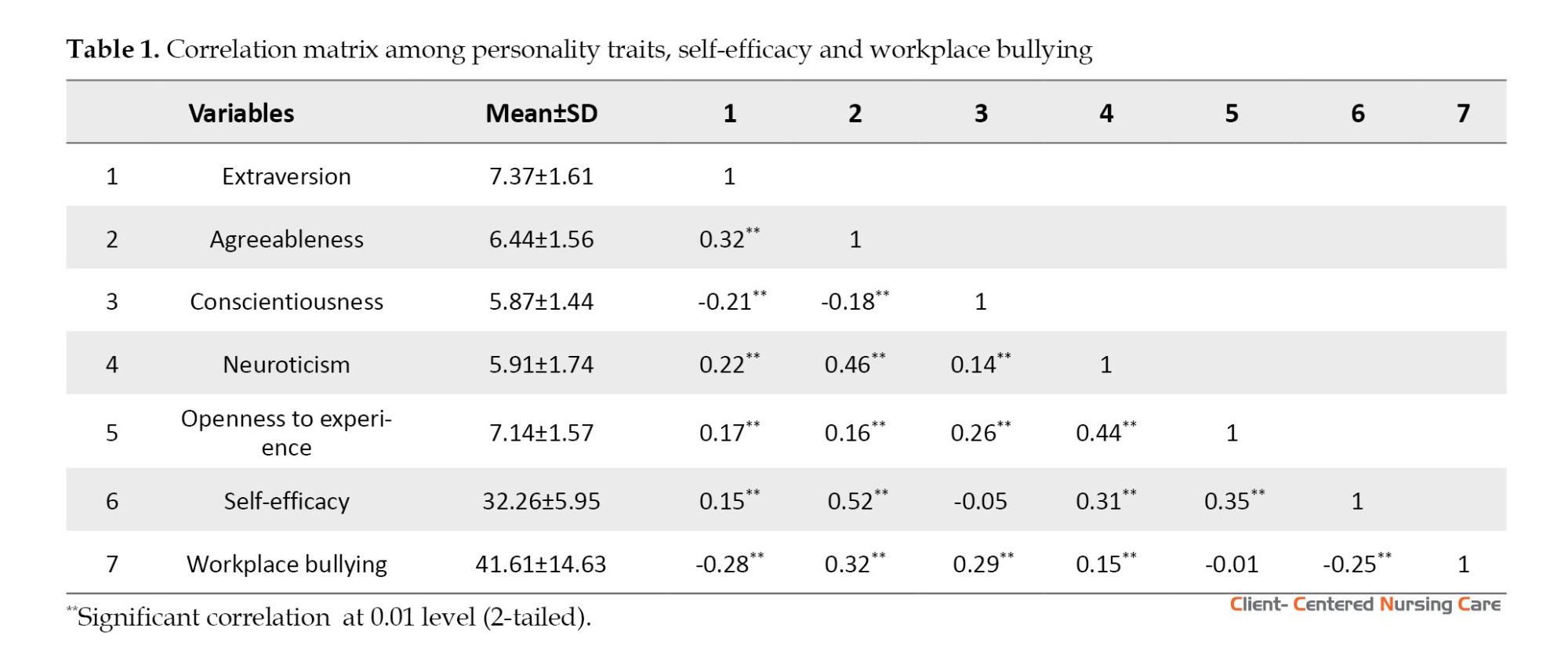

Bivariate correlations

Before the hypotheses were tested, bivariate correlations were computed to determine the extent and direction of relationships among the study variables.

Results of the correlation analysis presented in Table 1 revealed a significant negative association between extraversion and workplace bullying (r=-0.28, P<0.01), implying that high extraversion tends to decrease workplace bullying. There was also a significant link between agreeableness and workplace bullying (r=0.32, P<0.01). Similarly, conscientiousness and workplace bullying had a significant positive connection (r=0.29, P<0.01). Furthermore, there was a significant positive connection between neuroticism and workplace bullying (r=0.15, P<0.01). Finally, there was a significant negative relationship between self-efficacy and workplace bullying (r=-0.25, P<0.01).

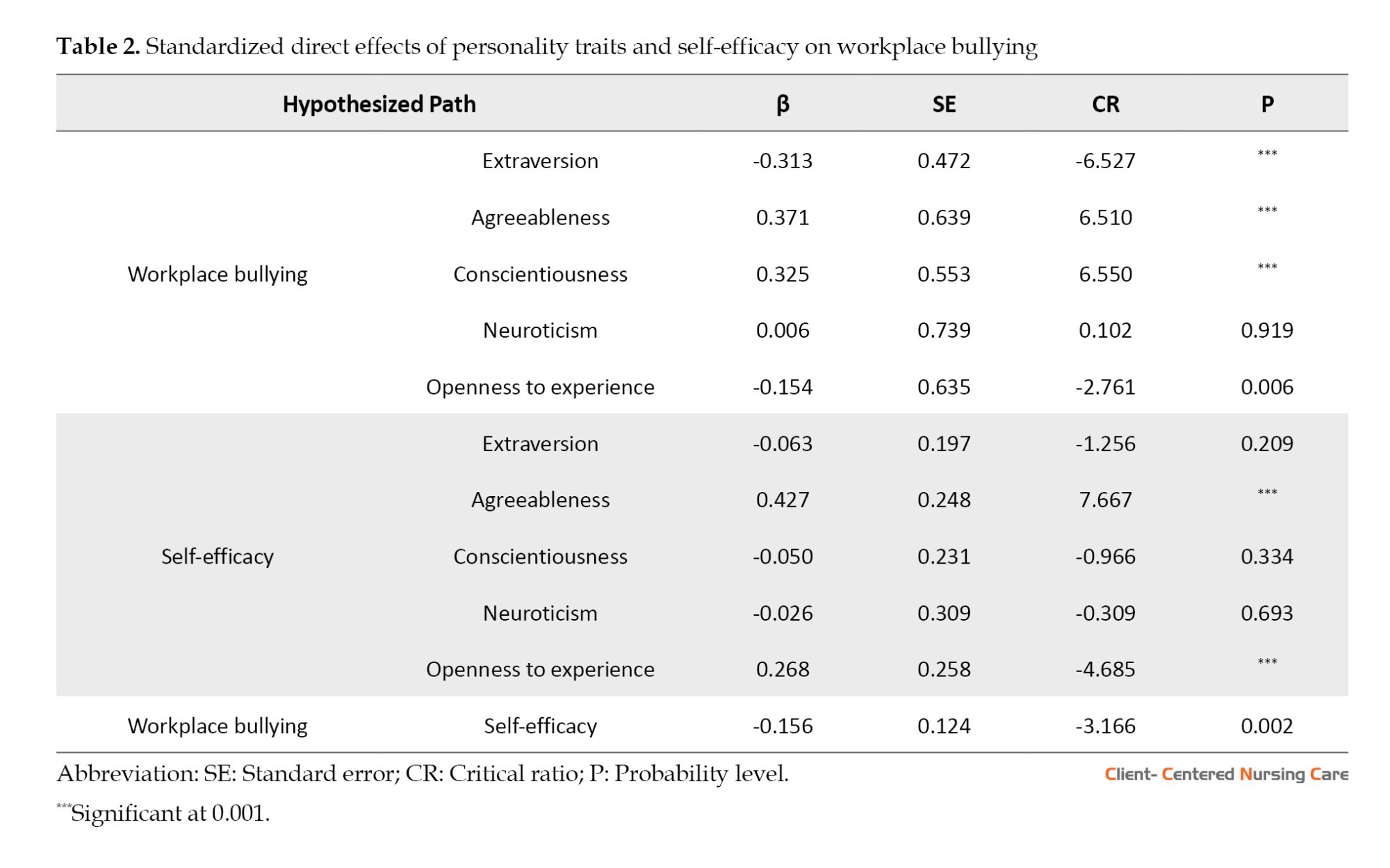

Hypotheses and mediation test

SEM with the MLE was used in the study to assess the measurement and structural model. The measurement model seeks to determine if the sample data are consistent with the factor structure of the variables in the hypothesized model.

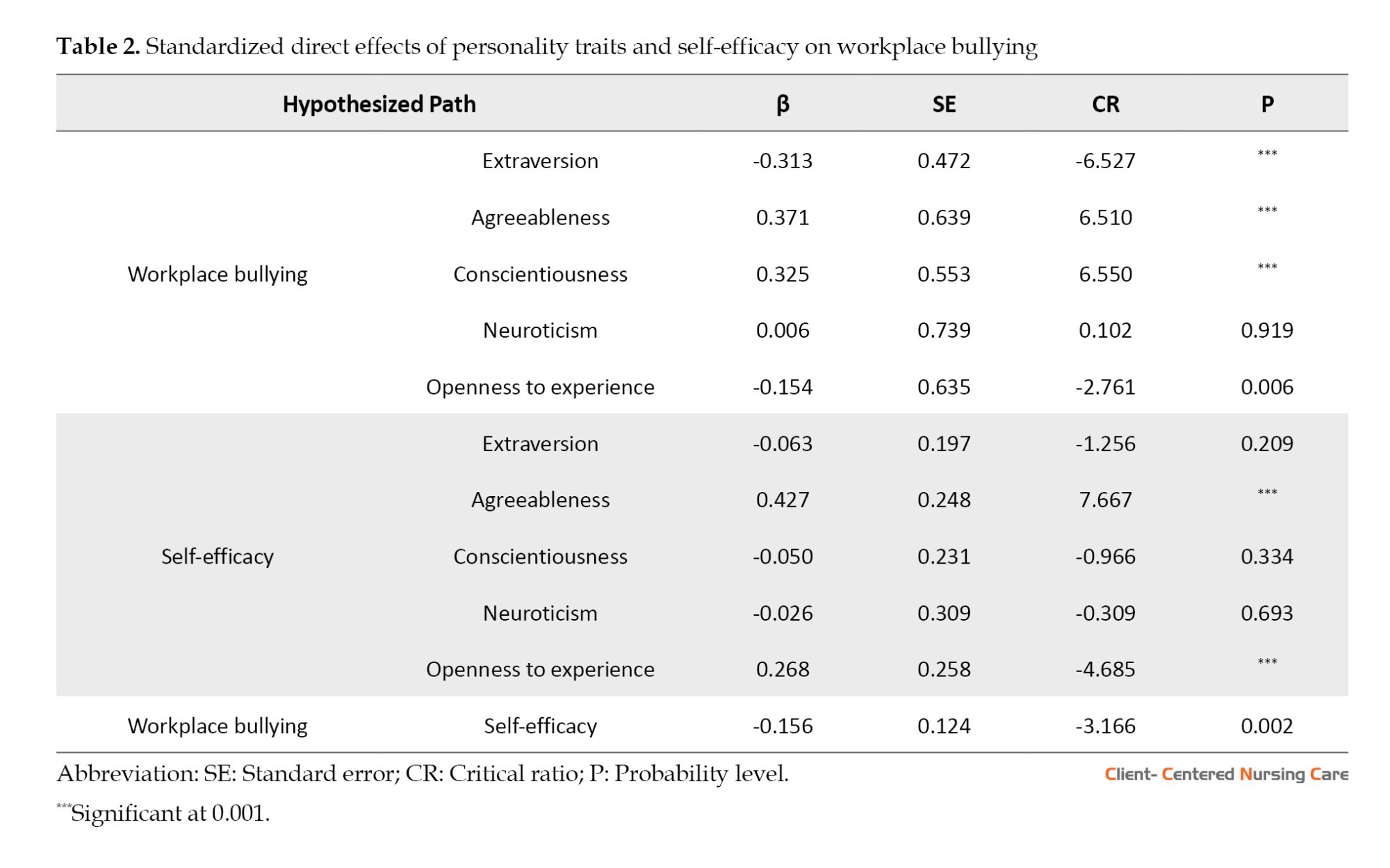

This condition needed several confirmatory factors analysis (CFA) of all the variables. After covariates and deletion of items, the model accepted a good measurement model fit: the relative chi-square χ2/df=2.352, goodness of fit index (GFI)=0.921, adjusted (A) GFI=0.807, comparative fit index (CFI)=0.923, normed fit index (NFI)=0.983, Tucker Lewis index (TLI)=0.901, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)=0.064. We also assessed the measurement model’s construct, convergent and discriminant validity and discovered that all of the variables of construct reliability coefficients satisfied Hair et al. (2010) criteria. Next, we utilized the MLE with a bootstrapping approach to run the structural model to evaluate the hypothesized model. Hair et al. (2010) state that at least three indicators are good for fitting a model. At first, the hypothesized model did not achieve the recommended model fit, but after suggested covariance between error terms of items, the model eventually fit well. In this study, the model achieves good fit indices: Relative chi-square χ2/df=1.819, P=0.000, GFI=0.851, AGFI=0.917, CFI=0.921, NFI=0.843, TLI=0.801 and RMSEA=0.053. The full structural equation model (direct and indirect) is presented in Figure 2, Tables 2 and 3.

The results of the first hypothesis showed that the extraversion trait (β=-0.313, P<0.001) negatively predicts workplace bullying, the agreeableness trait (β=0.371, P<0.001) positively predicts workplace bullying, and conscientiousness (β=0.325, P<0.001) positively relates with workplace bullying. However, no significant relationship was found between neuroticism and workplace bullying (β=0.006, P>0.05). There was also a negative association between openness to experience and workplace bullying (β=-0.154, P<0.001). The second hypothesis found that the extraversion trait (β=-0.063, P>0.05) is not related to self-efficacy, agreeableness trait (β=0.427, P<0.001) predict self-efficacy, and conscientiousness (β=-0.050, P>0.05) and neuroticism (β=-0.026, P>0.05) do not predict self-efficacy, but openness to experience trait (β=-0.268, P<0.001) predict self-efficacy. The third hypothesis also found that self-efficacy (β=-0.156, P<0.05) predict workplace bullying. Regarding mediation analysis, the results in Table 3 indicate that self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between agreeableness traits and workplace bullying (β=-0.067, 95% CI, 0.028%, 0.114%, P=0.001). The study also indicates that self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between openness to experience and workplace bullying (β=-0.042, 95% CI, 0.016%, 0.074%, P=0.001). The results support the third hypothesis.

Discussion

Using the SEM, this study investigated the role of personality traits in workplace bullying through self-efficacy among nurses in a public hospital in Nigeria. The study findings supported our hypotheses. Our study found that among personality traits, extraversion negatively predicted workplace bullying, while agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience positively predicted workplace bullying. The study finding was in line with Jang et al. (2023), who found that personality traits predicted workplace bullying among nurses in South Korea. This finding also aligned with previous studies that agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, and emotional stability predicted workplace bullying incidents (Munir et al., 2021; Nielsen and Knardahl, 2015). Halim et al. (2018) concluded that only conscientiousness could influence workplace bullying among 340 registered nurses. The study was also in accordance with Rai and Agarwal (2019), who found an inverse relationship between extraversion and workplace bullying among 835 permanent Indian managers working in diverse Indian organizations. In our study, neuroticism did not predict workplace bullying, which is inconsistent with other studies that found neuroticism traits positively predicted workplace bullying (John et al., 2021; Olapegba et al., 2020). The justification may be that the reaction to negative events can differ due to individual personality differences. For instance, nurses with high extroversion are often energetic and sociable; hence, their sociability may help them not to experience any form of bullying at work. On the other hand, nurses who are skeptical and untrustworthy always fail to demonstrate performance standards, which makes them prone to stressful situations and, in the long run, may make them experience workplace bullying.

The second hypothesis revealed that self-efficacy has predicted workplace bullying. This finding was consistent with past studies, which showed that high self-efficacy reduces bullying intention (Hsieh et al.,2019). Nurses with high self-efficacy have the confidence to protect themselves from being exposed to bullying at work.

In line with our third hypothesis, the association between personality traits (openness to experience and agreeableness) and workplace bullying was indirectly influenced by self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a protective factor in reducing workplace bullying incidents among nurses. This finding agrees with previous studies that self-efficacy serves as a buffer in the exposure to bullying behaviors and reduction of any mental health challenges (Yao et al., 2018; Kwiatosz-Muc et al., 2021). This study also supports social cognitive theory. When nurses have high self-efficacy, it acts as a personal buffer or resource that can help mitigate workplace bullying, especially among agreeable and open to experiencing traits.

This study faced some limitations that must be recognized. Data were collected from only one public hospital in Nigeria. Therefore, caution should be taken when extrapolating the findings to nurses working in other hospitals in different areas. Furthermore, this study’s cross-sectional design reduces the likelihood that the factors under investigation will have causal impacts on one another. Also, the measuring tools in the study could be subject to some form of bias as a result of the social desirability effect from the respondents.

Theoretical and practical implications

The present study builds on existing workplace bullying research by considering the Nigerian context, where similar studies have not been explored. The study strengthens the theoretical foundations of past research conducted by Li et al. (2020), Bukhari et al. (2022) and Kwiatosz-Muc et al. (2021) regarding nurses and other employees by shedding more light on the specific pathways through which self-efficacy operates to influence workplace bullying. An additional theoretical contribution is that different personality traits predispose workplace bullying among Nigerian nurses. Hence, nurses’ traits may continue to determine their perception of workplace bullying. This, therefore, calls for psychological interventions that may help build personality and self-efficacy, which in turn can reduce the menace of workplace bullying.

The findings also have some practical implications. Since personality traits of nurses predict workplace bullying, it is recommended that professional psychologists develop personality screening tools to detect traits such as agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience so that early personality modification intervention can be introduced to such nurses. Also, since self-efficacy mediates the relationship between personality traits (agreeableness and openness to experience) and workplace bullying, in practical terms, nursing professionals should design self-efficacy skill training programs that can help build personal resources that can be used to mitigate or cope with any stressful situations that may result in bullying incidents in the workplace. Finally, self-efficacy training can be added into nurses’ professional careers before entering the nursing profession; this will give them the necessary skills to cope with any negative related bullying behavior.

Conclusion

This study was the first to investigate personality traits, self-efficacy, and workplace bullying behavior among 371 nurses in Nigeria. We concluded that personality traits were vital in predicting workplace bullying among Nigerian nurses. Also, personality traits predicted self-efficacy. It was also concluded that self-efficacy mediated the link between personality and workplace bullying. Future studies should study more nurses from other parts of the world. Also, qualitative studies using interviews and focus group discussions could help improve the study’s findings. Future studies with particular emphasis on the perpetrator of bullying may explore other psychosocial factors such as organizational climate, abusive supervisor, etc.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Obafemi Awolowo University (Code: FSS/OAU/RREC/0235). This study adhered strictly to the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, amended in 2000, and the ethical guidelines set forth by the responsible committee on human testing.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Dare Azeez Fagbenro; Data collection: Mathew Olugbenga Olasupo; Study design and data interpretation: Dare Azeez Fagbenroo and Sulaiman Sikirulai Alausa; Writing the original draft: Dare Azeez Fagbenro and Mathew Olugbenga Olasupo; Review and editing: Erhabor Sunday Idemudia, Dare Azeez Fagbenro and Mathew Olugbenga Olasupo; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the nurses who took their valuable time to participate.

References

Workplace bullying, especially in the nursing profession, is a serious, persistent and devastating social problem that has continued to generate immense research attention among concerned health stakeholders in the world and a developing economy like Nigeria (Johnston et al., 2010; Nwaneri et al., 2017; Homayuni et al., 2021). Bullying is a work stressor that disrupts nurses’ healthy workplace environment and has a seriously deleterious effect on their well-being and performance (Munir et al., 2020; Homayuni et al., 2021). Workplace bullying refers to repetitive and constant negative behaviors directed toward an employee or their work, leading to low dignity and self-worth (Haq et al., 2018). This illicit behavior may result from work-related or personal issues, mainly by workers, supervisors, or colleagues (Einarsen, 2000; Namie & Namie, 2009). The typical workplace bullying among nurses includes non-verbal aspersion, verbal abuse, hidden information, withdrawing effort, disrupting, breaching, gloating, backbiting and broken trust (Salin, 2015). Worldwide, 39.7% of nurses have been victims of workplace bullying (Johnson, 2021) and in Nigeria, little has been documented on nurses’ bullying. Afolaranmi et al. (2022) reported that 59.7% of Nigerian health workers, including nurses, reported bullying with derogatory remarks as one serious form of bullying. Recently, Omole (2023) reported a high rate of bullying behaviors among nurses in Nigeria, with intimidation, malicious rumors, and unfair treatment as the most common forms of bullying experienced by nurses. Studies have shown that nurses who are bullied are likely to encounter different problems, such as headaches, hypertension, fatigue, insomnia, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, irritability, depression, psychological distress and burnout (Pai & Lee 2011; Rodwell et al., 2013). These problems have consequences for increased clinical errors on the part of nurses, reduced quality of patient care, absenteeism, and intention to quit their jobs (Trépanier et al., 2016). It, therefore, becomes relevant and important to offer preventive measures to eradicate this unacceptable behavior from the nursing profession.

Worldwide, many personal and organizational factors, such as organizational justice (Mohammed et al., 2018), psychological and sociodemographic factors (Akanni et al., 2020), job demands (Mokhtar et al., 2021), negative affect, role conflict and core self-evaluations (Homayuni et al., 2021) have been antecedents to workplace bullying. Most studies mentioned above have yielded inconclusive results, with most done in the Western world. The literature has relatively limited investigation of personality traits and workplace bullying among Nigerian nurses. The mechanism underlying the link between personality traits and workplace bullying through self-efficacy is also scarce in the extant literature.

According to Sadock (2003), personality is the distinct pattern of ideas, emotions, and behaviors that lasts over time and in various contexts. The broad traits constitute a complete individual’s personality and are labeled as extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience (Bolger & Zuckerman 1995), known as the big five personality traits. Extraversion is seen in activities that intensify energy as a necessary ingredient for motivation, sought from outside or external cues (Paunonen & Ashton, 2001). According to Tobin et al. (2010), agreeableness is a quality most commonly associated with interpersonal relationships and describes the types of interactions an individual prefers. According to De Raad (2000), conscientiousness is the drive to accomplish something, exemplified by thinking, self-control, and goal-oriented behavior. Neuroticism or emotional stability refers to frequent levels of emotional regulation and instability (Costa & McCrae 1992). Alarcon et al. (2009) stated that “being open to experience” was actively seeking and enjoying new experiences. There has been abundant research on personality traits and workplace bullying behavior. For instance, Jang et al. (2023) found that personality traits predicted workplace bullying among nurses in South Korea. John et al. (2021) also found that the big five personality characteristics, specifically neuroticism, play a vital role in victimization from workplace bullying. Olapegba et al. (2020) found that neuroticism trait predicted workplace bullying among 368 university staff. In their study, Rai and Agarwal (2019) found that conscientiousness, agreeableness, extraversion and openness to experience negatively correlate with workplace bullying. Halim et al. (2018) also determined that only conscientiousness influenced workplace bullying among 340 registered nurses. Also, Nielsen and Knardahl (2015) found a relationship between extraversion and workplace bullying. Munir et al. (2021) found a significant influence of agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experiences of workplace bullying. Ojedokun et al. (2014) also found that personality traits significantly affected workplace bullying. Studies in the literature have also found an association between agreeableness and bullying incidence (Seigne et al., 2007), an inverse association between agreeableness and bullying incidence, and a link between neuroticism and bullying incidence (Turner & Ireland, 2010). Despite their significance, they yielded different and conflicting results. Therefore, scholars and researchers have advocated for more empirical investigation into the precursors of workplace bullying (Coyne et al., 2000; Glasø et al., 2007; Nielsen and Knardahl, 2015). In a bid to address this call, the present study examines the direct role of personality traits and the indirect role of self-efficacy in workplace bullying, especially among nurses in a developing country like Nigeria, where bullying among nurses is a serious challenge (Omole, 2023).

Self-efficacy is a variable that may act as a possible mechanism in the relationship between personality traits and workplace bullying. Bandura (1999) defined self-efficacy as an individual belief in successfully executing and accomplishing a task in a particular situation. Higher levels of self-efficacy make a person feel more capable of meeting challenges head-on and overcoming setbacks; as a result, they are more confident in their capacity to finish a challenging activity (Bandura 1982). Self-efficacy is often considered a resource that helps ameliorate stressors at work. Therefore, self-efficacy may act as a protective buffer against workplace bullying for nurses with different traits. In incidences of bullying, personal perceptions of self-efficacy reduce the tendency to engage in negative emotions like stress, anxiety, and depression (Bandura, 1977). Additionally, higher self-efficacy may increase an individual’s self-confidence so they do not become the target of bullying and specifically protect nurses’ personalities from bullying at work. In this regard, the importance of this study lies in examining whether self-efficacy, as a useful protective factor, may help ease workplace bullying for Nigerian nurses with different personality traits.

Studies on the relationship between self-efficacy and workplace bullying are scarce and those who have looked at it have found inconclusive results, with none among nurses in Nigeria. For instance, Li et al. (2020) discovered an inverse association between self-esteem and the likelihood of reporting oneself as a victim of workplace bullying. Similarly, Bukhari et al. (2022) found an inverse relationship between workplace bullying and teacher self-efficacy. Kwiatosz-Muc et al. (2021) discovered that self-efficacy was positively related to conscientiousness, extraversion and openness to experience. Yao et al. (2018) found a connection between self-efficacy, extraversion, and neuroticism traits. In addition, Yu-hui et al. (2019) found that self-efficacy mediated the relationship between bullying and mental health and intention to leave. Also, Fang et al. (2021) found that social support mediated the relationship between workplace bullying and health problems. However, the extant literature has not investigated the indirect effect of self-efficacy in the relationship between personality traits and workplace bullying. We, therefore, presume that self-efficacy could mediate the association between personality traits and workplace bullying of Nigerian nurses.

Theoretically, we draw on social cognitive theory to examine the connections between personality traits, self-efficacy, and workplace bullying. According to the theory, those with high self-efficacy perceive difficult situations as challenges rather than threats. Conversely, those with self-doubt avoid challenging circumstances because they perceive them as dangers to their safety (Bandura, 1994). This means that nurses with high self-efficacy do not see bullying as a serious threat or challenge; instead, they believe they can cope with any adverse effect of the bullying incident. On the other hand, nurses with low self-efficacy see workplace bullying as a serious threat that they need to avoid; the inability to prevent the situation makes them experience negative emotions in the form of stress, anxiety, and depression, which, in the long run, affect their mental wellbeing.

This study aims to examine the predictive role of personality traits on workplace bullying, the role of personality traits in self-efficacy, the role of self-efficacy in workplace bullying, and the indirect role of self-efficacy in the relationship between personality and workplace bullying among nurses. The study’s results are expected to help healthcare professionals put up intervention programs that can help eradicate or minimize workplace bullying among nurses. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model and hypotheses of the study.

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedures

The study adopted a descriptive, cross-sectional design and was conducted at the University College Hospital (UCH) in Ibadan, Nigeria, in 2022. This hospital is one of the largest federal government-owned hospitals in Nigeria. According to Hair et al. (2017) recommendation, the sample size was estimated at 10 participants for each parameter. However, adding more participants increases the adequacy of the data to test the model. Therefore, this study utilized a sample size of 400. The inclusion criteria included full-time health workers in this hospital who consented to voluntary study participation. The head of the nursing unit of the UCH helped distribute the questionnaires to the nurses after the participants agreed to participate in the study. The data collection was assisted by two research assistants who distributed and recollected the questionnaires from the participants. Most questionnaires were filled out after working hours, and participants took approximately 15 minutes to complete the questionnaire. The whole exercise was completed in two weeks. Out of the 400 questionnaires administered, only 371 were filled out correctly, showing a response rate of 93%. The age range of these participants is 20–58 years old, with a Mean±SD age of 39.12±8.31 years. Their sex revealed that 66(23.7%) were males and 305(76.3%) were females. Respondents’ marital status showed that 81(21.8%) were single, 273(73.6%) married, 9(2.4%) widowed, 7(1.9%) separated and 1(.3%) divorced.

Measuring tools

Workplace bullying was assessed using the 22-item negative acts questionnaire-revised developed by Einarsen et al. (2009). This scale was used to draw individuals who have been bullied. It has three dimensions: work-related bullying, person-related bullying, and physically intimidating bullying. It is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=never to 5=always. A sample of the items follows: “I am being exposed to an unmanageable workload.” Higher scores on the scale translate to having been bullied and vice versa. The developers have reported a reliability of 0.90. In the current study, the Cronbach α of the scale was calculated as 0.92.

Personality traits were measured using the 10-item personality scale of big five inventory (BFI-10) developed by Rammstedt and John (2007). The scale has five dimensions: Extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience. Items 1R and 5 measured the dimension of extraversion, items 2 and 7R measured the dimension of agreeableness, and items 3R and 8 measured the conscientiousness dimension. Items 4R and 9 measure the domain of neuroticism, while items 5R and 10 measure the domain of openness to experience. ‘R’ means that items are reversed-scored. The scale used a response format of a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=disagree strongly, 2=disagree a little, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=agree a little and 5=agree strongly. A sample of the items on the scale is as follows, “I see myself as someone who tends to find fault with others.”

High scores on the traits mean high traits, while low scores on any of these traits indicate low traits. The authors of the scale reported a Cronbach α for the overall BFI-10 scale as 0.83, calculated as 0.71 for the whole scale in the present study.

The 10-item generalized self-efficacy scale (GSES) developed by Schwarzer and Jerusalem (1995) captured self-efficacy information on participants’ ability to engage in a task confidently. A sample item on the scale is as follows, “No matter what comes my way, I am usually able to handle it.” The response format ranges from 1=not at all true, 2=barely true, 3=moderately true, to 4=precisely true. The scores for each of the ten items are summed to give a total score; thus, the higher the score, the greater the individual generalized sense of self-efficacy. As reported by the author, the scale’s reliability ranges from 0.82 to 0.93 when examining diverse groups. In this study, a Cronbach α of 0.90 was reported.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics such as Mean±SD, and percentages were used to analyze the sociodemographic variables. The study’s hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM) and maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) with bootstrapping technique. The assumptions required regarding using SEM were met and the sample size, as recommended for SEM analysis, was above 200 (Kline 2010). Also, the Skewness and Kurtosis scores for the study data range from -0.90 to 2.30, within the range specified by Tabachnick and Fidell’s (2019) acceptable range of +2 and -2. The multicollinearity assumption was also ascertained using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance values. In this study, there was no multicollinearity issue as the tolerance value of the independent variables ranges between 0.54 and 0.82, which is within the stipulated threshold of >0.1. Also, VIF ranges from 1.20 to 1.83, within the range of <0.10 (Kline 2010). In line with Kline (2010), model fit was evaluated using the goodness of fit index (GFI, cut-off point ≥0.95), comparative fit index (CFI, cut-off point ≥0.90), normed fit index (NFI, cut-off point ≥0.90), Tucker Lewis index (TLI, cut-off point ≥0.90) and root mean square error of the approximation (RMSEA, cut-off point ≤0.07). SPSS software, version 23 were used to analyze the study data. The following hypotheses were tested:

1) Personality traits significantly predict workplace bullying; 2) Self-efficacy significantly predicts workplace bullying; 3) Self-efficacy significantly mediates the relationship between personality traits and workplace bullying.

Results

Bivariate correlations

Before the hypotheses were tested, bivariate correlations were computed to determine the extent and direction of relationships among the study variables.

Results of the correlation analysis presented in Table 1 revealed a significant negative association between extraversion and workplace bullying (r=-0.28, P<0.01), implying that high extraversion tends to decrease workplace bullying. There was also a significant link between agreeableness and workplace bullying (r=0.32, P<0.01). Similarly, conscientiousness and workplace bullying had a significant positive connection (r=0.29, P<0.01). Furthermore, there was a significant positive connection between neuroticism and workplace bullying (r=0.15, P<0.01). Finally, there was a significant negative relationship between self-efficacy and workplace bullying (r=-0.25, P<0.01).

Hypotheses and mediation test

SEM with the MLE was used in the study to assess the measurement and structural model. The measurement model seeks to determine if the sample data are consistent with the factor structure of the variables in the hypothesized model.

This condition needed several confirmatory factors analysis (CFA) of all the variables. After covariates and deletion of items, the model accepted a good measurement model fit: the relative chi-square χ2/df=2.352, goodness of fit index (GFI)=0.921, adjusted (A) GFI=0.807, comparative fit index (CFI)=0.923, normed fit index (NFI)=0.983, Tucker Lewis index (TLI)=0.901, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)=0.064. We also assessed the measurement model’s construct, convergent and discriminant validity and discovered that all of the variables of construct reliability coefficients satisfied Hair et al. (2010) criteria. Next, we utilized the MLE with a bootstrapping approach to run the structural model to evaluate the hypothesized model. Hair et al. (2010) state that at least three indicators are good for fitting a model. At first, the hypothesized model did not achieve the recommended model fit, but after suggested covariance between error terms of items, the model eventually fit well. In this study, the model achieves good fit indices: Relative chi-square χ2/df=1.819, P=0.000, GFI=0.851, AGFI=0.917, CFI=0.921, NFI=0.843, TLI=0.801 and RMSEA=0.053. The full structural equation model (direct and indirect) is presented in Figure 2, Tables 2 and 3.

The results of the first hypothesis showed that the extraversion trait (β=-0.313, P<0.001) negatively predicts workplace bullying, the agreeableness trait (β=0.371, P<0.001) positively predicts workplace bullying, and conscientiousness (β=0.325, P<0.001) positively relates with workplace bullying. However, no significant relationship was found between neuroticism and workplace bullying (β=0.006, P>0.05). There was also a negative association between openness to experience and workplace bullying (β=-0.154, P<0.001). The second hypothesis found that the extraversion trait (β=-0.063, P>0.05) is not related to self-efficacy, agreeableness trait (β=0.427, P<0.001) predict self-efficacy, and conscientiousness (β=-0.050, P>0.05) and neuroticism (β=-0.026, P>0.05) do not predict self-efficacy, but openness to experience trait (β=-0.268, P<0.001) predict self-efficacy. The third hypothesis also found that self-efficacy (β=-0.156, P<0.05) predict workplace bullying. Regarding mediation analysis, the results in Table 3 indicate that self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between agreeableness traits and workplace bullying (β=-0.067, 95% CI, 0.028%, 0.114%, P=0.001). The study also indicates that self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between openness to experience and workplace bullying (β=-0.042, 95% CI, 0.016%, 0.074%, P=0.001). The results support the third hypothesis.

Discussion

Using the SEM, this study investigated the role of personality traits in workplace bullying through self-efficacy among nurses in a public hospital in Nigeria. The study findings supported our hypotheses. Our study found that among personality traits, extraversion negatively predicted workplace bullying, while agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience positively predicted workplace bullying. The study finding was in line with Jang et al. (2023), who found that personality traits predicted workplace bullying among nurses in South Korea. This finding also aligned with previous studies that agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, and emotional stability predicted workplace bullying incidents (Munir et al., 2021; Nielsen and Knardahl, 2015). Halim et al. (2018) concluded that only conscientiousness could influence workplace bullying among 340 registered nurses. The study was also in accordance with Rai and Agarwal (2019), who found an inverse relationship between extraversion and workplace bullying among 835 permanent Indian managers working in diverse Indian organizations. In our study, neuroticism did not predict workplace bullying, which is inconsistent with other studies that found neuroticism traits positively predicted workplace bullying (John et al., 2021; Olapegba et al., 2020). The justification may be that the reaction to negative events can differ due to individual personality differences. For instance, nurses with high extroversion are often energetic and sociable; hence, their sociability may help them not to experience any form of bullying at work. On the other hand, nurses who are skeptical and untrustworthy always fail to demonstrate performance standards, which makes them prone to stressful situations and, in the long run, may make them experience workplace bullying.

The second hypothesis revealed that self-efficacy has predicted workplace bullying. This finding was consistent with past studies, which showed that high self-efficacy reduces bullying intention (Hsieh et al.,2019). Nurses with high self-efficacy have the confidence to protect themselves from being exposed to bullying at work.

In line with our third hypothesis, the association between personality traits (openness to experience and agreeableness) and workplace bullying was indirectly influenced by self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a protective factor in reducing workplace bullying incidents among nurses. This finding agrees with previous studies that self-efficacy serves as a buffer in the exposure to bullying behaviors and reduction of any mental health challenges (Yao et al., 2018; Kwiatosz-Muc et al., 2021). This study also supports social cognitive theory. When nurses have high self-efficacy, it acts as a personal buffer or resource that can help mitigate workplace bullying, especially among agreeable and open to experiencing traits.

This study faced some limitations that must be recognized. Data were collected from only one public hospital in Nigeria. Therefore, caution should be taken when extrapolating the findings to nurses working in other hospitals in different areas. Furthermore, this study’s cross-sectional design reduces the likelihood that the factors under investigation will have causal impacts on one another. Also, the measuring tools in the study could be subject to some form of bias as a result of the social desirability effect from the respondents.

Theoretical and practical implications

The present study builds on existing workplace bullying research by considering the Nigerian context, where similar studies have not been explored. The study strengthens the theoretical foundations of past research conducted by Li et al. (2020), Bukhari et al. (2022) and Kwiatosz-Muc et al. (2021) regarding nurses and other employees by shedding more light on the specific pathways through which self-efficacy operates to influence workplace bullying. An additional theoretical contribution is that different personality traits predispose workplace bullying among Nigerian nurses. Hence, nurses’ traits may continue to determine their perception of workplace bullying. This, therefore, calls for psychological interventions that may help build personality and self-efficacy, which in turn can reduce the menace of workplace bullying.

The findings also have some practical implications. Since personality traits of nurses predict workplace bullying, it is recommended that professional psychologists develop personality screening tools to detect traits such as agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience so that early personality modification intervention can be introduced to such nurses. Also, since self-efficacy mediates the relationship between personality traits (agreeableness and openness to experience) and workplace bullying, in practical terms, nursing professionals should design self-efficacy skill training programs that can help build personal resources that can be used to mitigate or cope with any stressful situations that may result in bullying incidents in the workplace. Finally, self-efficacy training can be added into nurses’ professional careers before entering the nursing profession; this will give them the necessary skills to cope with any negative related bullying behavior.

Conclusion

This study was the first to investigate personality traits, self-efficacy, and workplace bullying behavior among 371 nurses in Nigeria. We concluded that personality traits were vital in predicting workplace bullying among Nigerian nurses. Also, personality traits predicted self-efficacy. It was also concluded that self-efficacy mediated the link between personality and workplace bullying. Future studies should study more nurses from other parts of the world. Also, qualitative studies using interviews and focus group discussions could help improve the study’s findings. Future studies with particular emphasis on the perpetrator of bullying may explore other psychosocial factors such as organizational climate, abusive supervisor, etc.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Obafemi Awolowo University (Code: FSS/OAU/RREC/0235). This study adhered strictly to the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, amended in 2000, and the ethical guidelines set forth by the responsible committee on human testing.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Dare Azeez Fagbenro; Data collection: Mathew Olugbenga Olasupo; Study design and data interpretation: Dare Azeez Fagbenroo and Sulaiman Sikirulai Alausa; Writing the original draft: Dare Azeez Fagbenro and Mathew Olugbenga Olasupo; Review and editing: Erhabor Sunday Idemudia, Dare Azeez Fagbenro and Mathew Olugbenga Olasupo; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the nurses who took their valuable time to participate.

References

Afolaranmi, T. O., et al., 2022. Workplace bullying and its associated factors among medical doctors in residency training in a Tertiary Health Institution in Plateau State Nigeria. Frontier Public Heath, 9, pp. 812979. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2021.812979] [PMID] [PMCID]

Akanni, O. O., et al., 2020. Predictors of bullying reported by perpetrators in a sample of senior school students in Benin City, Nigeria. South African Journal Psychiatry, 26, pp. 1359. [DOI:10.4102/sajpsychiatry. v26i0.1359] [PMID] [PMCID]

Bandura, A., 1999. A social cognitive theory of personality. In L. Pervin & O. John (Eds.), Hnadbook of personality (pp. 154-196). New York: Guildford Publications. [Link]

Bandura A., 1977. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behav-iour change. Psychology Revision, 84(2), pp. 191-215, [DOI:10.1037//0033-295X.84.2.191] [PMID]

Bandura, A., 1982. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), pp. 122-47. [DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122]

Bandura, A., 1994. Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (pp. 71-81). New York: Academic Press. [Link]

Bukhari S., Akhter N. & Fida F., 2022. The impact of workplace bullying on university teachers’ self-efficacy: Mediating role of the university environment. The Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government, 28(2), pp.190-213. [Link]

Bolger N., & Zuckerman A., 1995. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychiatry, 69(5), pp. 890–902. [DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.890] [PMID]

Coyne, I., Seigne, E. & Randall, P., 2000. Predicting workplace victim status from personality. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 9(3), pp. 335-49. [DOI:10.1080/135943200417957]

Costa, P. & McCrae, R. R. (1992b). Neo PI-R professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assess-ment Resources. [Link]

De Raad, B., 2000. The big five personality factors. A Psycho-lexical Approach to Personality. Cambridge: Hogrefe and Huber Publishers. [Link]

Einarsen, S., 2000. Harassment and bullying at work: A review of the Scandinavian approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5(4), pp. 379-401. [DOI:10.1016/S1359-1789(98)00043-3]

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H. & Notelaers G., 2009. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work & Stress, 23(1), pp.24-44. [DOI:10.1080/02678370902815673]

Fang, L., et al., 2021. Workplace bullying, personality traits and health among hospital nurses: The mediating effect of social support. Journal Clinical Nursing, 30(23-24), pp. 3590-600. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.15881]

Glasø, L., et al., 2007. Do targets of workplace bullying portray ageneral victim personality profile? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 48(4), pp. 313-9. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00554.x] [PMID]

Halim, H. A. M., Halim, F. W. & Khairuddin, R., 2018. Does personality influence workplace bullying and lead to depression among nurses? Jurnal Pengurusan, 53(14), pp. 3-12. [Link]

Hair, F. J., et al., 2017. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. [Link]

Haq, M. R., Zia-ud-Din, M. & Rajvi, S., 2018. The impact of workplace bullying on employee cynicism with mediating role of psychological contract. International Journal Academic Research Business Social Science, 8(8), pp. 127-37. [DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i8/4445]

Homayuni, A., et al., 2021. Which nurses are victims of bullying: The role of negative affect, core self-evaluations, role conflict and bullying in the nursing staff. BMC Nursing, 20(1), pp. 57. [PMID] [PMCID]

Hsieh, Y. H., Wang, H. H. & Ma, S. C., 2019. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between workplace bullying, mental health and an intention to leave among nurses in Taiwan. Interntional Journal Occupational Medical Environment Health, 32(2), pp. 245-54. [DOI:10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01322] [PMID]

Jang, S., Kim, E. & Lee, E., 2023. Effects of personality traits and mentalization on workplace bullying experiences among Intensive Care Unit Nurses. Journal of Nursing Management.[DOI:10.1155/2023/5360734]

John, B., Bhattacharya, S. & Chawda, R., 2021. Personality antecedents and consequences of workplace bullying among faculty members at higher educational institutes in Central India. Ilkogretim Online, 20(5), pp. 2071. [Link]

Johnson, S. L., 2021. Workplace bullying in the nursing profession. In: P. D'Cruz, E. Noronha, L. Keashly, & S. Tye-Williams, (Eds), Special topics and particular occupations, professions and sectors. Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment, vol 4. Singapore: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-981-10-5308-5_14]

Johnston, J., Phanhtharath, P. & Jackson, B., 2010. The bullying aspect of workplace violence in nursing. JONA's Healthcare Law, Ethics, and Regulation, 12(2), pp. 36-42. [DOI:10.1097/NHL.0b013e3181e6bd19] [PMID]

Kline R. B., 2010. Principles and practices of structural equation modelling. New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Kwiatosz-Muc, M., Kotus, M. & Aftyka, A., 2021. Personality Traits and the sense of self-efficacy among Nurse Anaesthetists. Multi-Centre Questionnaire Survey. International Journal Environment Research Public Health, 18(17), pp. 9381. [PMID] [PMCID]

Li, X., Li, X. & Chen, W., 2020. The impact of workplace bullying on employees’ turnover intention: The role of self-esteem. Optimal Journal of Social Science, 8(10), pp. 23-34. [DOI:10.4236/jss.2020.810003]

Mohamed, H., Higazee, M. Z. A. & Goda, S., 2018. Organizational Justice and Workplace Bullying: The experience of nurses. American Journal of Nursing Research, 6(4), pp. 208-13. [Link]

Mokhtar D., Halim M. F. A. & Nor N., 2021. The Influence of Job Demands on Workplace Bullying Experience among Healthcare Employees. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting Financial and Management Science, 11, pp. 223-34. [DOI:10.6007/IJARAFMS/v11-i3/10873]

Munir M., Ali M. & Haider SK., 2021. Investigating personality traits as the antecedents of workplace bullying. International Revision of Management and Business Research, 10, pp. 135-49. [DOI:10.30543/10-1(2021)-11]

Munir M., Attiq, S. & Zafar, M. Z., 2020. Can incidence of workplace bullying really be reduced? Application of the trans theoretical model as tertiary stage anti-bullying intervention. Pakistan Business Revision, 21(4), pp. 762-77. [Link]

Namie G. & Namie, R., 2009. The bully at work: What you can do to stop the hurt and reclaim your dignity on the job. Naperville: Sourcebooks, Inc. [Link]

Nielsen, M. B. & Knardahl, S., 2015. Is workplace bullying related to the personality traits of victims? A two-year prospective study. Work & Stress, 29(2), pp. 128-49. [DOI:10.1080/02678373.2015.1032383]

Nwaneri, C., Onoka, C. & Onoka, A., 2017. Workplace bullying among nurses working in tertiary hospitals in Enugu, southeast Nigeria: Implications for health workers and job performance. Journal Nursing Education and Practice, 2, pp. 69-78. [DOI:10.5430/jnep.v7n2p69]

Ojedokun O., Oteri, I. & Ogungbamila, A., 2014. Which of the big-five trait is more predictive of workplace bullying among academics in Nigeria? Nigeria Journal of Applied Behaviour Science, 2(1), pp. 184-203. [Link]

Olapegba, O., Famakinde, O. & Okeke, C., 2020. Personality and organizational factors as predictors of workplace bullying in selected universities in Nigeria. A Journal of Research and development, 7(1), pp. 135-65. [Link]

Omole, O. R., 2023. Effects of workplace bullying and burnout on job satisfaction among nurses in Sokoto State, Nigeria. Asian Journal of Research in Nursing and Health, 6(1), pp. 297-308. [Link]

Pai, H. C. & Lee, S., 2011. Risk factors for workplace violence in clinical registered nurses in Taiwan. Journal Clinical Nursing, 20(9-10), pp. 1405-12. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03650.x]

Paunonen, S. V. & Ashton, M. C., 2001. Big five factors and facets and the prediction of behaviour. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(3), pp. 524–39. [DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.81.3.524] [PMID]

Rai, A. & Agarwal, A., 2019. Examining the relationship between personality traits and exposure to workplace bullying. Global Business Review, 20(4), pp. 1069-87 [DOI:10.1177/0972150919844883]

Rammstedt, B. & John O. P., 2007. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10 item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), pp. 203-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001]

Rodwell, J., Demir D. & Steane P., 2013. Psychological and organizational impact of bullying over and above negative affectivity: A survey of two nursing contexts. International Journal Nursing Practice, 19(3), pp. 241-8. [DOI:10.1111/ijn.12065] [PMID]

Salin, D., 2015. Risk factors of workplace bullying for men and women: The role of the psychosocial and physical work environment. Scandenvian Journal Psychology, 56(1), pp. 69-77. [DOI:10.1111/sjop.12169] [PMID]

Schwarzer, R. & Jerusalem, M., 1995. Generalized Self-Efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35-37). New York: Windsor. [DOI:10.1037/t00393-000]

Seigne E., et al., 2007. Personality traits of bullies as a contributory factor in workplace bullying: An exploratory study. International Journal of Organisational Theoretical & Behaviour, 10 (1), pp. 118-32. [DOI:10.1108/IJOTB-10-01-2007-B006]

Tobin, R. M., et al., 2010. Personality, emotional experience, and efforts to control emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, pp. 656-69. [DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.79.4.656] [PMID]

Trépanier, S. G., et al., 2016. Work environment antecedents of bullying: A review and integrative model applied to registered nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 55, pp. 85–97. [PMID]

Turner P. & Ireland, J. L., 2010. Do personality characteristics and beliefs predict intra-group bullying between prisoners? Aggressive Behaviour, 36(4), pp. 261-70. [DOI:10.1002/ab.20346] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2023/11/22 | Accepted: 2024/03/6 | Published: 2024/08/1

Received: 2023/11/22 | Accepted: 2024/03/6 | Published: 2024/08/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |