Tue, Jul 1, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 10, Issue 3 (Summer 2024)

JCCNC 2024, 10(3): 155-166 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Malekitabar A, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee A, Falsafinejad M R, Vakili S. Exploring Spouse Selection Concerns Among Men With Visual Impairments. JCCNC 2024; 10 (3) :155-166

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-567-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-567-en.html

Alireza Malekitabar1

, Anahita Khodabakhshi-Koolaee *2

, Anahita Khodabakhshi-Koolaee *2

, Mohammad Reza Falsafinejad3

, Mohammad Reza Falsafinejad3

, Samira Vakili1

, Samira Vakili1

, Anahita Khodabakhshi-Koolaee *2

, Anahita Khodabakhshi-Koolaee *2

, Mohammad Reza Falsafinejad3

, Mohammad Reza Falsafinejad3

, Samira Vakili1

, Samira Vakili1

1- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Khatam University, Tehran, Iran. ,a.khodabakhshid@khatam.ac.ir

3- Department of Assessment and Measurement, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Khatam University, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Assessment and Measurement, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 573 kb]

(392 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1713 Views)

Full-Text: (376 Views)

Introduction

Avisually impaired person has visual acuity between 20/70 and 20/400 or a visual field of ≤20 degrees. Professionals use visual impairment (VI) to describe any vision loss, whether someone has no vision or partial vision loss. The term blindness is also used for complete or almost complete loss of sight (WHO, 2023). VI is a significant public health issue worldwide, which has an irreparable impact on an individual’s mental and emotional health and financial state, as well as the well-being of the family, community and country (Otuka, 2021). There are about 36 million completely blind, 217 million with moderate to severe VI and 253 million people with mild VI around the world (Ezinne et al., 2022). The available data up to 2023 indicate that In Iran, 865127 people with mild to severe VI are covered by the Welfare Organization, which constitutes 13.5% of the country’s disabled people. Besides, 722212 of VI people are female and 142915 are male (State Welfare Organization of Iran, 2023).

Blindness and low vision are challenges that cause affected people to face many psychological and social problems (Bhagchandani, 2014). Visually impaired people face psychological and social problems, lack of independent life, incompatibility with urban space and public transportation, and poor participation in social activities (Aslan et al., 2012).

Some studies have shown that people with VI are less aware of their physical and mental changes due to limited social relationships and lack of contact with the surrounding environment (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Amoogholi, 2024). Negative attitudes of family and significant others can lead to the internalization of negative self-esteem in visually impaired people and restrict their participation in the community, the workforce, and the family. VI is associated with negative public perceptions, making marriage difficult for affected people (Chilwarwar & Sriram, 2019). People with VI show higher levels of depression and loneliness compared to their sighted peers (Pinquart & Pfeiffer, 2011). These people often receive adverse reactions from their peers regarding their physical attractiveness and suitability as spouses (Gordon, 2004). Furthermore, some people in the community do not agree with the marriage of disabled people under any circumstances and consider only healthy people to be entitled to this right. Some people also think that disabled people do not need to get married (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Amoogholi, 2024).

Satvat et al. (2018) reported four challenges of the marriage faced by persons with physical/motor disabilities: “negative feelings and attitudes about marriage,” “family concerns and pressures,” “social stigma and public rejection,” and “inadequate support resources and white employment.” Pinquart & Pfeiffer, (2011) investigated establishing and maintaining intimate relationships with spouses among visually impaired people. They concluded that visually impaired people have fewer opportunities to meet mates because of the tendency to spend more time alone, an inability to assess partners visually, and adverse reactions when courting sighted peers. Thus, they have some problems establishing long-term intimate relationships with their spouses.

Research shows that spouse selection and creating a warm and intimate relationship are key life goals for most people (Kapperman & Kelly, 2019), and establishing romantic relationships is essential for most people, including people with physical disabilities (Pinquart & Pfeiffer, 2011). Besides, the experience of an efficient marital life can solve many emotional and psychological problems for these people (Schulz, 2008).

Compared to single persons, married ones are less prone to depression and have lower rates of suicide and physical problems. They are also more likely to report happiness and life satisfaction and live longer (Braithwaite et al., 2010). Hence, one of the ways that visually impaired people can do to improve their health is to establish intimate relationships and marry the person they love. Spouse selection studies have suggested that people of both sexes like their partner to be kind, sympathetic, reliable, sociable, emotionally stable and intelligent. They also want their partner to be honest, kind, considerate, loyal and interesting (Conroy-Beam & Buss, 2016). However, beyond these similarities, gender differences in spouse selection prevail in various communities and cultures.

Finding a good partner depends on the ability to see and judge a person’s suitability. Moreover, primary communication depends on the ability to communicate using the power of vision and judge the appropriateness of a prospective spouse. Meanwhile, blind people are deprived of the power of sight, which challenges spouse selection in these people (Kapperman & Kelly, 2019). Kapperman & Kelly, (2019) also found that blind and visually impaired men pay attention to facial features, hair, waist size, age, education and financial conditions in spouse selection.

Chilwarwar & Sriram, (2019) reported that compared to men, women prefer older partners and consider VI an irrelevant and disturbing factor in choosing a life partner. Besides, women prefer men with good financial conditions, chastity, good behavior with parents and interest in family and children. In contrast, men wanted a physically attractive and capable partner.

However, there are contradictory findings in this field. For example, in research, the role of vision in the emergence of mate preferences was investigated in two groups of sighted and visually impaired people. The results showed that blind women chose physical and appearance attractiveness more than their blind male counterparts. However, visually impaired individuals considered auditory cues more important than visual cues (Scheller et al., 2021).

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Amoogholi, (2024) examined the psychological and social experiences of visually impaired girls regarding spouse selection. They concluded that visually impaired girls are scared and worried about their future married life. They are afraid of speaking about vision problems, inability to do housework, rejection and judgment from the husband’s family, rejection by the partner, and giving birth to children with disabilities.

In a research on the problems faced by the marriage of people with physical-motor disabilities in Iran, the results showed that family pressures and their insistence on marriage, having independence and escaping from the family atmosphere, and feeling of not being a burden were the challenges of marriage in disabled people (Satvat et al., 2018).

Mate selection and preferences are considered very important in marriage for all people. However, most studies have addressed spouse selection in sighted communities. Moreover, studies on family knowledge and rehabilitation, VI and psychological care have less frequently focused on the marriage of disabled people, especially marriage and the process of spouse selection in men with VI. The desire to have separate individuality from the family, marriage proposing as a selection by men in Iran, and the strong desire to have an independent life in people with VI led to current research. Thus, using a descriptive phenomenological approach, the present study sought to explore young men’s experiences with VI regarding mate preferences and spouse selection in the Iranian community.

Materials and Methods

The present study adopted a qualitative-descriptive phenomenological approach. According to Edmond Husserl, descriptive phenomenology, as a research method, explores and describes a person’s lived experience and is grounded on the main beliefs of natural attitude, intentionality, and phenomenological reduction (Smith, 2020; Praveena & Sasikumar, 2021). This study focused on blind and visually impaired men who were members of the Blind and Visually Impaired Association of Iran, Markazi Province, Arak Branch, Iran, in 2023. The Iranian Society for the Blind was established in 1992. This association is run as a charity, familiarizes Iranian society with the rights of visually impaired citizens, and tries to achieve their rights as the most important goal of this association. It also has branches in the provincial centers of Iran.

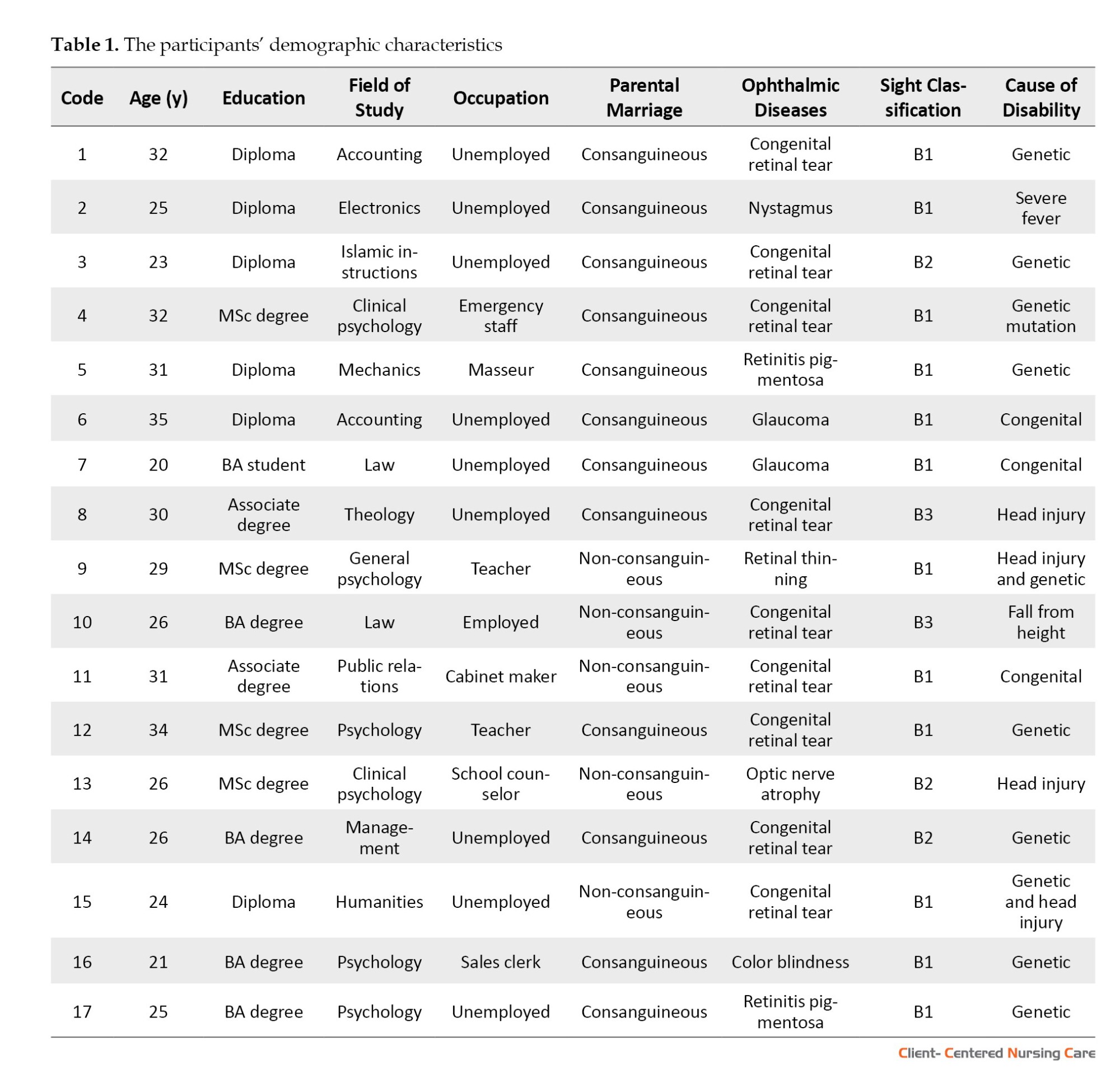

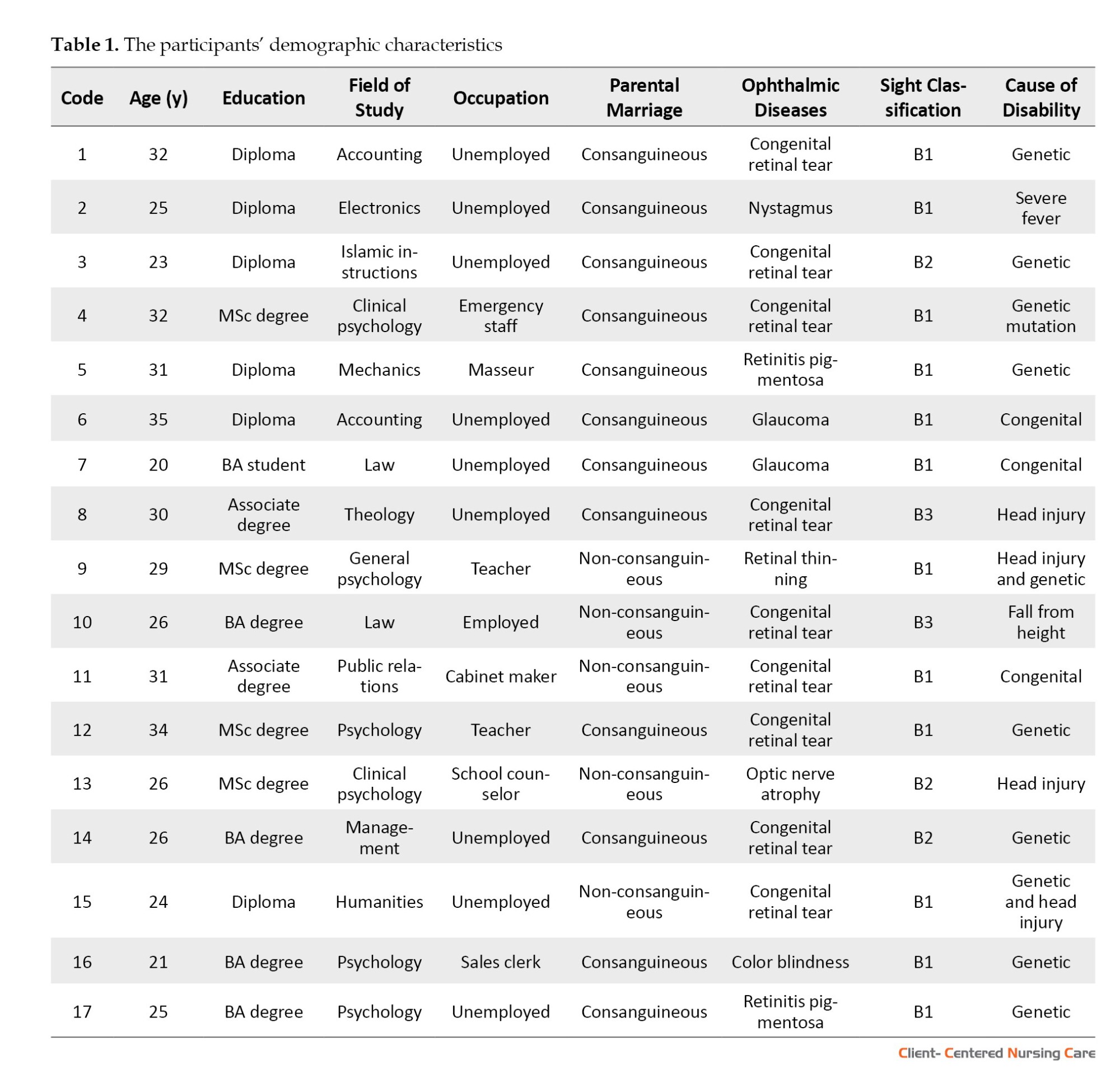

The participants were selected through purposive sampling, which was continued until the data saturation. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Having VI records in the Welfare Department, 2) Holding at least a diploma to understand and answer the interview questions, 3) Being of marriageable age (20 to 35 years), 4) Lacking other physical and mental disabilities except for VI and 5) Not getting married yet. To observe the principle of maximum variation sampling, the researchers took samples from different socioeconomic conditions and areas of Arak City, with varying levels of education.

Accordingly, the data were saturated after interviewing 17 blind and visually impaired men. All interviews were conducted face-to-face for 8 months, from March to October 2023. The data were collected using semi-structured, in-depth interviews. The interviews were conducted in compliance with ethical protocols. Before the interviews were conducted, written consent was obtained from the participants. They were also assured that their information would be kept anonymous and confidential. The time of the interviews was appointed through phone calls. All the interviews were conducted in the Blind Association. Each interview lasted 30 to 70 minutes (720 minutes in total).

First, the participants’ demographic data, such as age, education, employment, field of study, parents’ consanguineous or non-consanguineous marriage, ophthalmic diseases, sight classifications, cause of disability, and residence status, were recorded. Afterward, the interview questions were asked. The questions were developed based on the research question focusing on the participants’ lived experiences about marriage and love. The first question was, “What are your feelings about marriage and spouse selection?” Other questions were developed based on the participants’ answers for the following interview. At the end of each interview session, the participants were asked to add their further comments, if any. Examples of the questions asked in the interviews were as follows: What is your experience of choosing a spouse? What concerns do you have about marriage? Probing questions (e.g. Can you give an example? And what was your reaction at that point?) were also asked to elicit more information. At the end of each interview, the recorded interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed.

Data analysis was performed using Colaizzi’s (1978) 7-step analysis method (Morrow et al., 2015). In the first step, the participants’ statements were transcribed verbatim and then read several times to get a general impression of their content. The second step identified and highlighted the significant statements related to the phenomenon in question. Primary themes reflecting the participants’ ideas were extracted in the third step (formulation of meanings). Besides, the extracted themes were checked for relevance to the underlined statements. In the fourth step, the identified themes were placed into thematic clusters based on their similarities. In the fifth step, a thorough description of the phenomenon was formed. In the sixth step, the fundamental structure of the phenomenon was described. In the seventh step, the extracted main themes were discussed with the participants to see if the researchers could understand their experiences. This step was done so that if the participants’ experiences were not correctly understood, the researchers could return to the previous steps and redo the analysis. Bracketing (or epoche) may be a preparatory act within the phenomenological analysis, conceived by Husserl as suspending the belief in the world’s objectivity (Dörfler & Stierand, 2021). In the current research, the researchers kept bracketing in mind, tried to set aside their presuppositions and biases, and approached the experiences with an open and unbiased perspective.

Data trustworthiness was confirmed using the criteria proposed by Guba and Lincoln (2001). To do this, maximum variation sampling and prolonged engagement were used. Two independent researchers performed data analysis. The extracted categories were presented to the participants to check their validity and accuracy and were modified in case of any discrepancy. Ambiguities or questions were resolved through telephone follow-ups. The process of doing the work, analyses and themes were provided to the supervisors and consultants for verification. In addition, the data and analysis processes were provided to three external evaluators (ophthalmologist, nurse specialist and rehabilitation consultant) who were familiar with the phenomenological approach. To confirm transferability, a thick description of the study context was performed.

Table 1 presents the participants’ demographic characteristics. It should be mentioned that all the participants lived in their parents’ houses.

Results

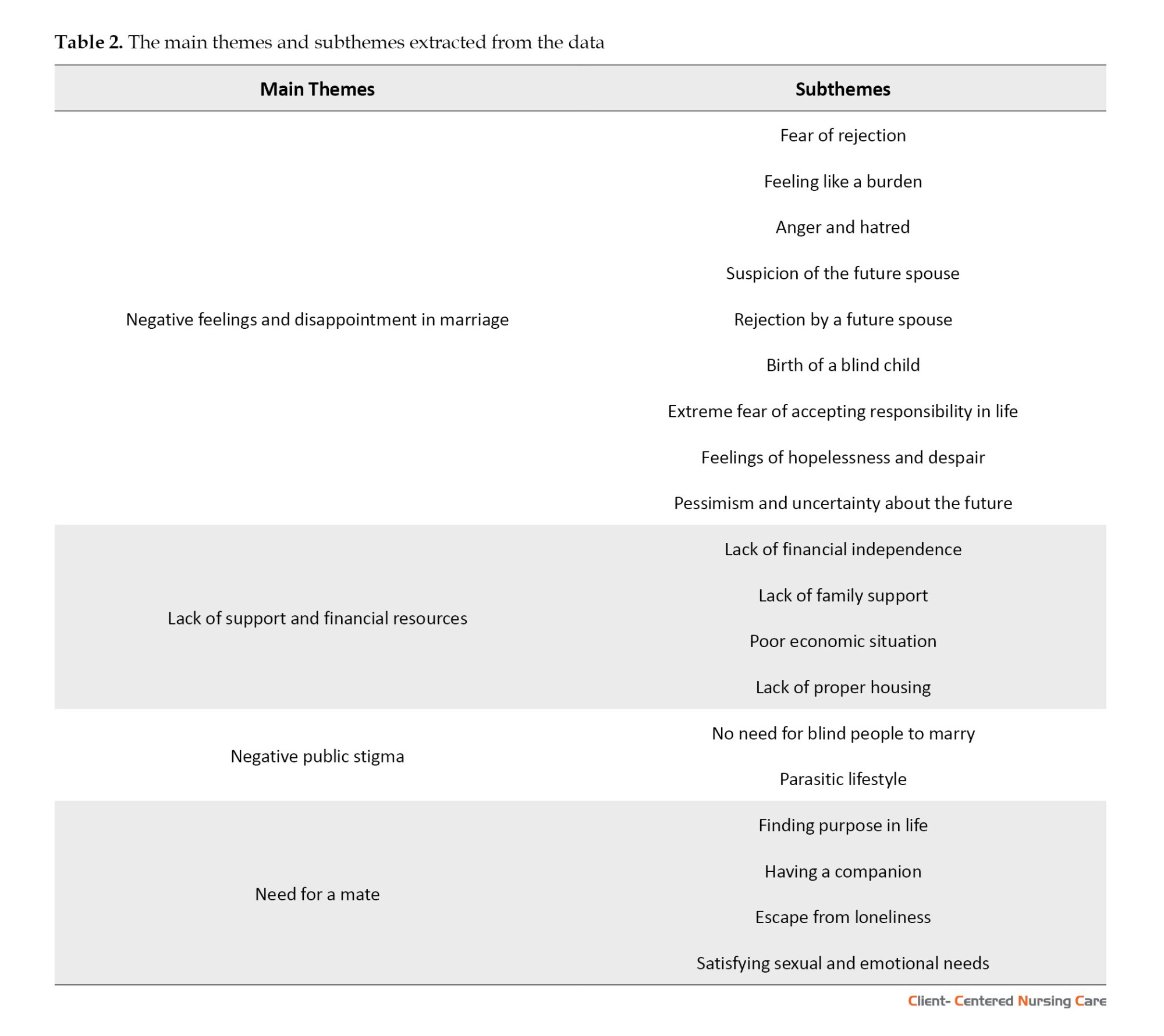

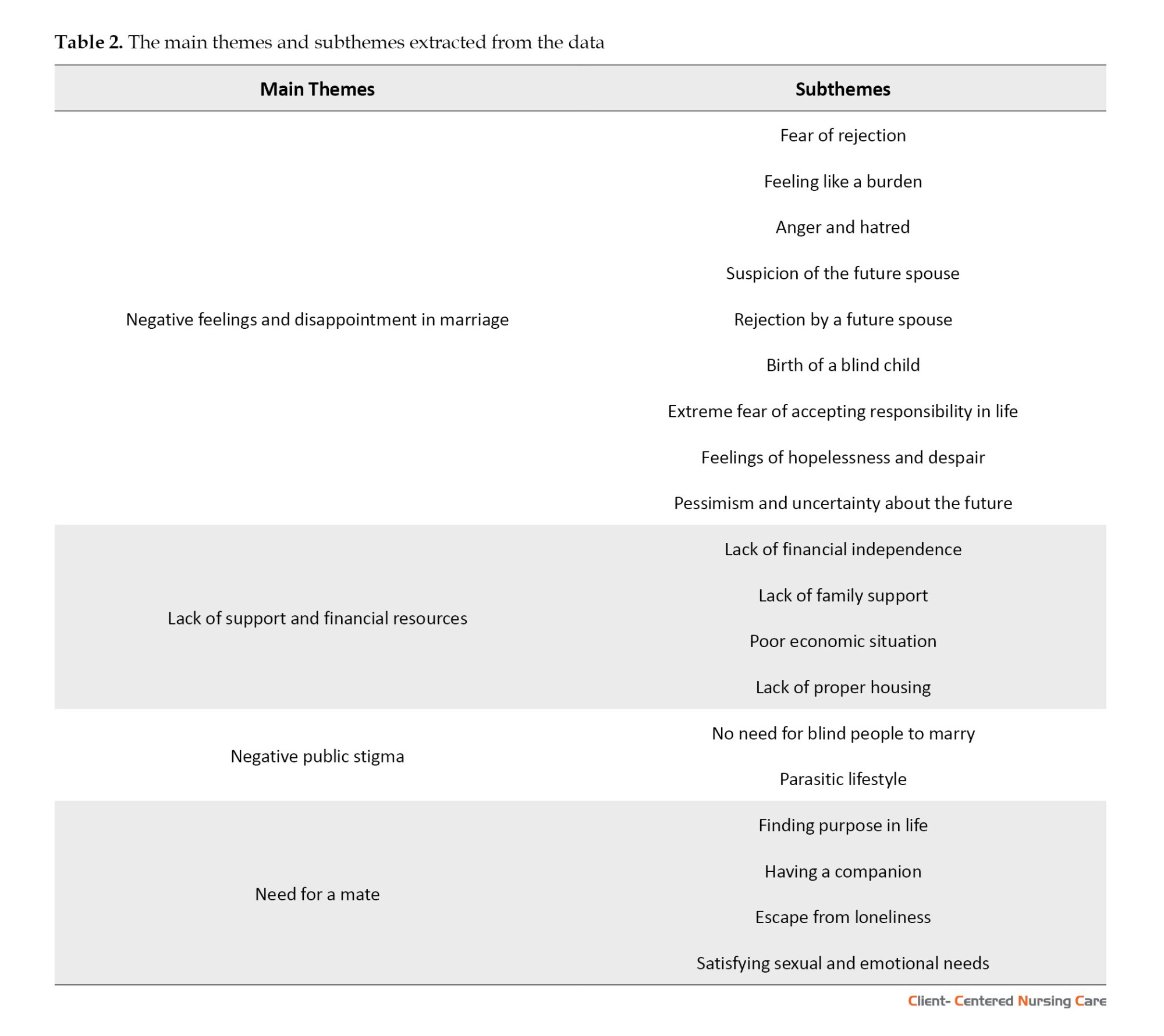

Data analysis revealed 4 main themes and 19 subthemes (Table 2).

Negative feelings and disappointment in marriage

This main theme consisted of 9 subthemes: Fear of rejection, feeling like a burden, anger and hatred, suspicion of a future spouse, rejection by the future spouse, the birth of a blind child, extreme fear of accepting responsibility in life, feelings of hopelessness and despair, and pessimism and uncertainty about the future. In the following, each subtheme is discussed.

Fear of rejection: The participants suffered from the fear of rejection. As a person, they were concerned about their shortcomings, which others might judge: “No one would accept to marry me with these physical conditions. I fear that the condition gets worse. I might not be able to get married. It would offend me if someone rejects my request for marriage” (Participant (P) 1).

Feeling like a burden: Feeling like a burden is a dynamic cognitive state that makes a person consider himself/herself an extra being in the family and community and feel depressed and hopeless in the long term. “What good did I do for my family? Nothing. I felt I was an extra being since I couldn’t be the same as everyone else. My disabilities make me feel this way. I can’t be independent like everyone else. I come to this conclusion from inside” (P 16).

Feelings of anger and hatred: Anger and hatred as negative feelings occurred due to participants’ emotional stimulation, sudden harassment, or disappointment about an issue: “A guy said we (people with disabilities) were born to be a lesson to others. Thus, there’s no point in being sad anymore. I always say to God that He has created me as a blind person, and I’ll tolerate it as much as I can, but He should give me all other things. God says He helps those who help themselves. I don’t ask Him how, when, and where. I’m sure He will help me with His blessings” (P 3).

Suspicion of the future spouse: Trust is the foundation of any relationship. If this trust is lost, the emotional relationship will break down. Suspicion of the spouse brings many challenges to marital life: “We, visually impaired people, are afraid that our partners would betray us. For example, she may find a better person. That’s why I try to be the best so that this doesn’t happen” (P 17).

Rejection by a future spouse: When people are rejected by their partners, they feel neglected and unlovable. Feeling insecure because of a threatening situation can cause harm and affect how a person’s relationships develop: “I think this will happen because of my vision problems. My biggest worry is that my future partner will leave me because of my vision problems” (P 13).

Birth of a blind child: Naturally, the result of any marriage is the birth of a child who can be healthy or have a disability. Accepting a child with a disability is very difficult for healthy parents. Still, it is quite a disaster for parents who have disabilities themselves: “I don’t want a person to come in this world who looks like me and has my problem and suffers the same pain that I suffered” (P 3).

Extreme fear of accepting responsibility in life: Blind people are afraid of accepting responsibility and commitment to work because they cannot handle their personal affairs and life like healthy people: “I’m afraid that I will not be able to fulfill my obligations in married life. I fear I cannot make a good life for my spouse if I cannot find a job. So, I don’t feel like getting married because of this fear” (P 2).

Feelings of hopelessness and despair: A feeling of hopelessness or despair adversely affected the participants’ health and social relationships. It could lead to depression and suicide and loss of purposeful efforts: “If I could see when I was young, I would have enjoyed my life more. I don’t have much time because I am 30 and still single. I will live 60 or 70 years at most. Perhaps, I might live another 30 years” (P 1).

Pessimism and uncertainty about the future: The participants believed that nothing was going well and it seemed unlikely that their wishes or goals would be fulfilled due to financial problems, unemployment, the inability to do things, and having no control over the environment: “When I think about my future, I get very depressed. I feel that there is no way out” (P 8).

Lack of support and financial resources

This main theme consisted of 4 subthemes: Lack of financial independence, lack of family support, poor financial conditions and lack of proper housing. In the following, each subtheme is discussed.

Lack of financial independence: Because of financial dependence, they could not meet the expenses of their lives without depending on others. They needed others to support them financially: “When I was a student, I wanted to get married. But besides my blindness, I didn’t have a job or a good source of income to lead an independent life. Therefore, I did not marry. There were a few girls I liked, but I didn’t propose to them and I didn’t even think about marriage. You should never get married when you don’t have a good job and income” (P 9).

Lack of family support: The family plays a vital role in marriage and spouse selection. The participants were upset that the family did not take action to achieve their happiness and marriage: “Family is very important. It would be great if they didn’t forget us. I don’t know why they wait and don’t do anything until our marriage age passes and we can no longer get married and find our favorite case” (P 10).

Poor economic conditions: Poor economic conditions can adversely affect choosing a spouse and starting a family. The participants pointed out that employment and meeting the basic needs are necessary to start a family: “Sometimes when we talk about marriage, people say that inflation and prices are too high and we can’t get married anymore. They talk about marriage expenses. For example, they say one should have 200 million Tomans (Iran currency) to pay for gold and jewelry and 500 million Tomans to pay for wedding costs” (P 6).

Lack of proper housing: Having a house is one of the most important things to start a family: “Because I didn’t have any income, I didn’t think about marriage at all, but with the help of my father, we did a few jobs, and I earned some money to buy a house and a car. Then, in 2021, I thought about getting married” (P 4).

Negative public stigma

This main theme consists of two subthemes: No need for blind people to get married and a parasitic lifestyle. In the following, each subtheme is discussed.

No need for blind people to get married: The participants believed that the main problem faced by blind people is that healthy people do not understand them and do not believe in their abilities to manage their lives: “Public awareness should be raised so that people come to the belief that marrying blind people is not so bad. They are also humans and have some skills. They should give blind people a chance” (P 7).

Parasitic lifestyle: Because people with VI have difficulty in doing their lives, others often think that they have a parasitic lifestyle; this view can be one of the obstacles to their marriage. The participants were worried that they would be a burden on their future spouses: “I am looking for an employed wife as she can help me in my life. If she is employed, I will have more job security (P 13).

Need for a mate

This main theme consisted of four subthemes: Finding a purpose in life, having a companion, escaping from loneliness, and satisfying sexual and emotional needs. In the following, each subtheme is discussed.

Finding a purpose in life: The participants were looking for a way to find a definite purpose to continue their lives. They wanted to experience self-confidence, motivation, and love for life; marriage was one of their most important goals. “A purpose gives meaning to my life. I didn’t have a plan for my life. If I get married, maybe I will have a plan for my life. I will find a job or pursue a business, I can live like other people” (P 1).

Having a companion: Persons with VI consider marriage a family foundation and an essential factor for the :union: and empathy of two people and the basis for their growth. The participants expressed that having a companion gives life meaning and saves a person from living aimlessly. “When you get married, you get peace of mind as there is someone who accepts you with all your problems and disabilities and you can choose someone that you love, and you will have a pleasant feeling” (P 14).

Escape from loneliness: The participants felt lonely due to the problems they faced in their marriage, which led to feelings of emptiness, rejection and unwantedness in them: “In my opinion, everyone needs a person to be by their side throughout their life, free them from loneliness and help them with their problems and life” (P 15).

Satisfying sexual and emotional needs: The participants believed that the best way to satisfy sexual instincts is to use natural ways based on the cultural norms of the society, and they felt that they could be satisfied through an emotional connection with the opposite sex: “It’s not just a sexual need. There are also emotional needs. Thus, you have someone who is waiting at home, loves you, and has prepared everything for you. And you can satisfy your need for sex with her” (P 10).

Discussion

The present study investigated the topic of marriage and love among blind and visually impaired men. The findings showed that blind and visually impaired men have negative and hopeless feelings towards spouse selection and marriage due to fear of rejection, feeling like a burden, feelings of anger and hatred, suspicion towards the future spouse, rejection by the future spouse, the birth of a blind child, extreme fear of accepting responsibility in life, feelings of despair and pessimism, and uncertainty about the future. In a similar vein, Satvat et al. (2018) examined the challenges of the marriage of physically disabled people. They found that these people have negative feelings and attitudes toward marriage and experience challenges such as feeling like a burden, running away from their current life, feeling ashamed, and not feeling happy because of celibacy, irrational and unrealistic expectations of marriage, inability to bear a child, and non-acceptance of physical conditions of people with physical disabilities.

One of the concerns of blind and visually-impaired people is the fear of not being accepted by their future life partner, which can be due to the problems caused by VI, making them unable to handle life affairs like their sighted counterparts. As a result, they suffer from low self-esteem and self-confidence. Docia and Silverstein (2020) reported increasing levels of depression and anxiety among people with VI. Döner (2015) also found that rejection by a potential partner due to VI or having concerns about the possibility of rejection was widespread among adults with visual disabilities.

The findings from the present study showed that visually impaired men feel that they have a parasitic lifestyle, so they can meet their needs by relying on their future spouse. This feeling is induced by the problems these people face in handling their life affairs and lack financial independence. Kapperman & Kelly, (2019) also showed that one of the spouse selection criteria for men with VI is the financial condition of their future spouse.

People with VI, like any other human beings, need to satisfy their sexual and emotional needs. Moreover, to fill their leisure time and escape loneliness, they need a permanent life partner who makes them strive harder to achieve their goals. Enoch et al. (2018) showed that various reasons cause disabled people to get married. These reasons range from caring for and supporting a life partner to fulfilling gender roles, being recognized in society, and wanting to become a parent. In addition, people with VI do not differ from sighted people in their preferences in choosing a spouse; the main problem is finding a life partner and having an intimate relationship (Fekler et al., 2020).

There is a common belief that disabled people, especially visually impaired persons, do not need to get married. This belief probably originates from the fact that VI or disability can be considered the only characteristic of a person without considering their other characteristics and skills. Visually impaired people pay the price of this attitude in society due to the limitations caused by their vision problems. In this way, it is thought that marriage and family formation are not necessary for these people, and blind and visually impaired people do not need to get married. Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Amoogholi, (2024) reported a negative public attitude regarding the marriage of visually impaired people. They also showed that one of the challenges of marrying blind and partially sighted girls is the attitude that there is no need for blind people to marry. Enoch et al. (2018) showed that society has discriminated against people with disabilities throughout history, which affects their participation in society. This condition may negatively impact their lives by limiting and making it more difficult for them to participate in society. These people face many social and financial challenges in their marriages. Moreover, Döner (2015) showed that people with VI face various forms of discrimination concerning having sexual relations and finding a life partner, including prejudices, humiliation, and receiving worrying questions about VI and sexuality. All of these problems became barriers to starting and maintaining sexual relationships for people with VI. Even at the beginning of romantic relationships, which probably involved various aspects of sexual activities, the participants had difficulties due to public attitudes towards visual impairment, sexual desires and romantic relationships. Blind people look for a life partner to escape their loneliness. Anderson (2018) shows that disabled people experience higher social isolation, low self-esteem, and more depression than their non-disabled peers due to having less frequent social interactions.

Overall, the findings of the present study suggested that the emotional and psychological concerns and needs of men with VI concerning spouse selection are partially based on their lived experience as disabled persons, including their fear of finding a suitable spouse and worry about their future marital life. In addition, some of these concerns are rooted in negative public views, such as being a burden or not having the right to marry and start a family. Moreover, lacking employment and income adds to their concerns. However, their emotional, sexual and psychological needs to find a spouse are still there, not to mention social and family barriers to marriage. Rehabilitation programs for people with VI in Iran’s Welfare Organization system rely more on meeting immediate financial needs, such as subsidies or glasses and ophthalmologist visits to help these people. Meanwhile, the counseling rehabilitation needs of these people, including the need for independence, spouse selection, and having a job, are not addressed. The data in this study revealed the need to address the concerns and needs of people with VI in rehabilitation programs. In addition to genetic and medical counseling, developing counseling programs, psychological treatments and virtual and face-to-face databases is essential for people with VI to give them a chance to find a life partner.

The current research had some limitations. This descriptive phenomenological research was based on the lived experiences of the participants who lived in a specific cultural and social context (Arak City, Iran) and were members of the Iranian Blind Association, Arak City Branch. Therefore, the findings do not represent men’s lived experiences in the entire visually impaired population in Iran. However, most qualitative studies aim not to generalize but to provide a rich and contextual understanding of some aspect of the human experience through intensive study of a specific group.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that the spouse selection concerns of men with VI include adverse feelings and disappointment about marriage, lack of support and financial resources, negative public stigma and the need for a mate. Education, treatment, psychological rehabilitation, and building self-confidence are essential for blind and visually impaired people. Besides, raising public awareness can contribute to developing a new perspective on accepting disabled persons and planning their employment to meet their living costs. It is suggested that future studies explore the views and experiences of family members, such as parents and siblings of visually impaired people, regarding choosing a spouse. Also, conducting a grounded theory study can explore the process of selecting a spouse for the visually impaired. In addition, considering that VI prevents seeing the physical presence of the opposite sex, research on other mate selection criteria in visually impaired men (such as body odor, voice type and mental imagination of a life partner) can provide valuable data.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research (Code: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1401.254). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants for conducting and recording the interviews. The participants were also reassured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Alireza Malekitabar, approved by the Department of Counseling, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the officials of the Arak Welfare Organization and the participants who cooperated closely with them.

References

Avisually impaired person has visual acuity between 20/70 and 20/400 or a visual field of ≤20 degrees. Professionals use visual impairment (VI) to describe any vision loss, whether someone has no vision or partial vision loss. The term blindness is also used for complete or almost complete loss of sight (WHO, 2023). VI is a significant public health issue worldwide, which has an irreparable impact on an individual’s mental and emotional health and financial state, as well as the well-being of the family, community and country (Otuka, 2021). There are about 36 million completely blind, 217 million with moderate to severe VI and 253 million people with mild VI around the world (Ezinne et al., 2022). The available data up to 2023 indicate that In Iran, 865127 people with mild to severe VI are covered by the Welfare Organization, which constitutes 13.5% of the country’s disabled people. Besides, 722212 of VI people are female and 142915 are male (State Welfare Organization of Iran, 2023).

Blindness and low vision are challenges that cause affected people to face many psychological and social problems (Bhagchandani, 2014). Visually impaired people face psychological and social problems, lack of independent life, incompatibility with urban space and public transportation, and poor participation in social activities (Aslan et al., 2012).

Some studies have shown that people with VI are less aware of their physical and mental changes due to limited social relationships and lack of contact with the surrounding environment (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Amoogholi, 2024). Negative attitudes of family and significant others can lead to the internalization of negative self-esteem in visually impaired people and restrict their participation in the community, the workforce, and the family. VI is associated with negative public perceptions, making marriage difficult for affected people (Chilwarwar & Sriram, 2019). People with VI show higher levels of depression and loneliness compared to their sighted peers (Pinquart & Pfeiffer, 2011). These people often receive adverse reactions from their peers regarding their physical attractiveness and suitability as spouses (Gordon, 2004). Furthermore, some people in the community do not agree with the marriage of disabled people under any circumstances and consider only healthy people to be entitled to this right. Some people also think that disabled people do not need to get married (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Amoogholi, 2024).

Satvat et al. (2018) reported four challenges of the marriage faced by persons with physical/motor disabilities: “negative feelings and attitudes about marriage,” “family concerns and pressures,” “social stigma and public rejection,” and “inadequate support resources and white employment.” Pinquart & Pfeiffer, (2011) investigated establishing and maintaining intimate relationships with spouses among visually impaired people. They concluded that visually impaired people have fewer opportunities to meet mates because of the tendency to spend more time alone, an inability to assess partners visually, and adverse reactions when courting sighted peers. Thus, they have some problems establishing long-term intimate relationships with their spouses.

Research shows that spouse selection and creating a warm and intimate relationship are key life goals for most people (Kapperman & Kelly, 2019), and establishing romantic relationships is essential for most people, including people with physical disabilities (Pinquart & Pfeiffer, 2011). Besides, the experience of an efficient marital life can solve many emotional and psychological problems for these people (Schulz, 2008).

Compared to single persons, married ones are less prone to depression and have lower rates of suicide and physical problems. They are also more likely to report happiness and life satisfaction and live longer (Braithwaite et al., 2010). Hence, one of the ways that visually impaired people can do to improve their health is to establish intimate relationships and marry the person they love. Spouse selection studies have suggested that people of both sexes like their partner to be kind, sympathetic, reliable, sociable, emotionally stable and intelligent. They also want their partner to be honest, kind, considerate, loyal and interesting (Conroy-Beam & Buss, 2016). However, beyond these similarities, gender differences in spouse selection prevail in various communities and cultures.

Finding a good partner depends on the ability to see and judge a person’s suitability. Moreover, primary communication depends on the ability to communicate using the power of vision and judge the appropriateness of a prospective spouse. Meanwhile, blind people are deprived of the power of sight, which challenges spouse selection in these people (Kapperman & Kelly, 2019). Kapperman & Kelly, (2019) also found that blind and visually impaired men pay attention to facial features, hair, waist size, age, education and financial conditions in spouse selection.

Chilwarwar & Sriram, (2019) reported that compared to men, women prefer older partners and consider VI an irrelevant and disturbing factor in choosing a life partner. Besides, women prefer men with good financial conditions, chastity, good behavior with parents and interest in family and children. In contrast, men wanted a physically attractive and capable partner.

However, there are contradictory findings in this field. For example, in research, the role of vision in the emergence of mate preferences was investigated in two groups of sighted and visually impaired people. The results showed that blind women chose physical and appearance attractiveness more than their blind male counterparts. However, visually impaired individuals considered auditory cues more important than visual cues (Scheller et al., 2021).

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Amoogholi, (2024) examined the psychological and social experiences of visually impaired girls regarding spouse selection. They concluded that visually impaired girls are scared and worried about their future married life. They are afraid of speaking about vision problems, inability to do housework, rejection and judgment from the husband’s family, rejection by the partner, and giving birth to children with disabilities.

In a research on the problems faced by the marriage of people with physical-motor disabilities in Iran, the results showed that family pressures and their insistence on marriage, having independence and escaping from the family atmosphere, and feeling of not being a burden were the challenges of marriage in disabled people (Satvat et al., 2018).

Mate selection and preferences are considered very important in marriage for all people. However, most studies have addressed spouse selection in sighted communities. Moreover, studies on family knowledge and rehabilitation, VI and psychological care have less frequently focused on the marriage of disabled people, especially marriage and the process of spouse selection in men with VI. The desire to have separate individuality from the family, marriage proposing as a selection by men in Iran, and the strong desire to have an independent life in people with VI led to current research. Thus, using a descriptive phenomenological approach, the present study sought to explore young men’s experiences with VI regarding mate preferences and spouse selection in the Iranian community.

Materials and Methods

The present study adopted a qualitative-descriptive phenomenological approach. According to Edmond Husserl, descriptive phenomenology, as a research method, explores and describes a person’s lived experience and is grounded on the main beliefs of natural attitude, intentionality, and phenomenological reduction (Smith, 2020; Praveena & Sasikumar, 2021). This study focused on blind and visually impaired men who were members of the Blind and Visually Impaired Association of Iran, Markazi Province, Arak Branch, Iran, in 2023. The Iranian Society for the Blind was established in 1992. This association is run as a charity, familiarizes Iranian society with the rights of visually impaired citizens, and tries to achieve their rights as the most important goal of this association. It also has branches in the provincial centers of Iran.

The participants were selected through purposive sampling, which was continued until the data saturation. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Having VI records in the Welfare Department, 2) Holding at least a diploma to understand and answer the interview questions, 3) Being of marriageable age (20 to 35 years), 4) Lacking other physical and mental disabilities except for VI and 5) Not getting married yet. To observe the principle of maximum variation sampling, the researchers took samples from different socioeconomic conditions and areas of Arak City, with varying levels of education.

Accordingly, the data were saturated after interviewing 17 blind and visually impaired men. All interviews were conducted face-to-face for 8 months, from March to October 2023. The data were collected using semi-structured, in-depth interviews. The interviews were conducted in compliance with ethical protocols. Before the interviews were conducted, written consent was obtained from the participants. They were also assured that their information would be kept anonymous and confidential. The time of the interviews was appointed through phone calls. All the interviews were conducted in the Blind Association. Each interview lasted 30 to 70 minutes (720 minutes in total).

First, the participants’ demographic data, such as age, education, employment, field of study, parents’ consanguineous or non-consanguineous marriage, ophthalmic diseases, sight classifications, cause of disability, and residence status, were recorded. Afterward, the interview questions were asked. The questions were developed based on the research question focusing on the participants’ lived experiences about marriage and love. The first question was, “What are your feelings about marriage and spouse selection?” Other questions were developed based on the participants’ answers for the following interview. At the end of each interview session, the participants were asked to add their further comments, if any. Examples of the questions asked in the interviews were as follows: What is your experience of choosing a spouse? What concerns do you have about marriage? Probing questions (e.g. Can you give an example? And what was your reaction at that point?) were also asked to elicit more information. At the end of each interview, the recorded interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed.

Data analysis was performed using Colaizzi’s (1978) 7-step analysis method (Morrow et al., 2015). In the first step, the participants’ statements were transcribed verbatim and then read several times to get a general impression of their content. The second step identified and highlighted the significant statements related to the phenomenon in question. Primary themes reflecting the participants’ ideas were extracted in the third step (formulation of meanings). Besides, the extracted themes were checked for relevance to the underlined statements. In the fourth step, the identified themes were placed into thematic clusters based on their similarities. In the fifth step, a thorough description of the phenomenon was formed. In the sixth step, the fundamental structure of the phenomenon was described. In the seventh step, the extracted main themes were discussed with the participants to see if the researchers could understand their experiences. This step was done so that if the participants’ experiences were not correctly understood, the researchers could return to the previous steps and redo the analysis. Bracketing (or epoche) may be a preparatory act within the phenomenological analysis, conceived by Husserl as suspending the belief in the world’s objectivity (Dörfler & Stierand, 2021). In the current research, the researchers kept bracketing in mind, tried to set aside their presuppositions and biases, and approached the experiences with an open and unbiased perspective.

Data trustworthiness was confirmed using the criteria proposed by Guba and Lincoln (2001). To do this, maximum variation sampling and prolonged engagement were used. Two independent researchers performed data analysis. The extracted categories were presented to the participants to check their validity and accuracy and were modified in case of any discrepancy. Ambiguities or questions were resolved through telephone follow-ups. The process of doing the work, analyses and themes were provided to the supervisors and consultants for verification. In addition, the data and analysis processes were provided to three external evaluators (ophthalmologist, nurse specialist and rehabilitation consultant) who were familiar with the phenomenological approach. To confirm transferability, a thick description of the study context was performed.

Table 1 presents the participants’ demographic characteristics. It should be mentioned that all the participants lived in their parents’ houses.

Results

Data analysis revealed 4 main themes and 19 subthemes (Table 2).

Negative feelings and disappointment in marriage

This main theme consisted of 9 subthemes: Fear of rejection, feeling like a burden, anger and hatred, suspicion of a future spouse, rejection by the future spouse, the birth of a blind child, extreme fear of accepting responsibility in life, feelings of hopelessness and despair, and pessimism and uncertainty about the future. In the following, each subtheme is discussed.

Fear of rejection: The participants suffered from the fear of rejection. As a person, they were concerned about their shortcomings, which others might judge: “No one would accept to marry me with these physical conditions. I fear that the condition gets worse. I might not be able to get married. It would offend me if someone rejects my request for marriage” (Participant (P) 1).

Feeling like a burden: Feeling like a burden is a dynamic cognitive state that makes a person consider himself/herself an extra being in the family and community and feel depressed and hopeless in the long term. “What good did I do for my family? Nothing. I felt I was an extra being since I couldn’t be the same as everyone else. My disabilities make me feel this way. I can’t be independent like everyone else. I come to this conclusion from inside” (P 16).

Feelings of anger and hatred: Anger and hatred as negative feelings occurred due to participants’ emotional stimulation, sudden harassment, or disappointment about an issue: “A guy said we (people with disabilities) were born to be a lesson to others. Thus, there’s no point in being sad anymore. I always say to God that He has created me as a blind person, and I’ll tolerate it as much as I can, but He should give me all other things. God says He helps those who help themselves. I don’t ask Him how, when, and where. I’m sure He will help me with His blessings” (P 3).

Suspicion of the future spouse: Trust is the foundation of any relationship. If this trust is lost, the emotional relationship will break down. Suspicion of the spouse brings many challenges to marital life: “We, visually impaired people, are afraid that our partners would betray us. For example, she may find a better person. That’s why I try to be the best so that this doesn’t happen” (P 17).

Rejection by a future spouse: When people are rejected by their partners, they feel neglected and unlovable. Feeling insecure because of a threatening situation can cause harm and affect how a person’s relationships develop: “I think this will happen because of my vision problems. My biggest worry is that my future partner will leave me because of my vision problems” (P 13).

Birth of a blind child: Naturally, the result of any marriage is the birth of a child who can be healthy or have a disability. Accepting a child with a disability is very difficult for healthy parents. Still, it is quite a disaster for parents who have disabilities themselves: “I don’t want a person to come in this world who looks like me and has my problem and suffers the same pain that I suffered” (P 3).

Extreme fear of accepting responsibility in life: Blind people are afraid of accepting responsibility and commitment to work because they cannot handle their personal affairs and life like healthy people: “I’m afraid that I will not be able to fulfill my obligations in married life. I fear I cannot make a good life for my spouse if I cannot find a job. So, I don’t feel like getting married because of this fear” (P 2).

Feelings of hopelessness and despair: A feeling of hopelessness or despair adversely affected the participants’ health and social relationships. It could lead to depression and suicide and loss of purposeful efforts: “If I could see when I was young, I would have enjoyed my life more. I don’t have much time because I am 30 and still single. I will live 60 or 70 years at most. Perhaps, I might live another 30 years” (P 1).

Pessimism and uncertainty about the future: The participants believed that nothing was going well and it seemed unlikely that their wishes or goals would be fulfilled due to financial problems, unemployment, the inability to do things, and having no control over the environment: “When I think about my future, I get very depressed. I feel that there is no way out” (P 8).

Lack of support and financial resources

This main theme consisted of 4 subthemes: Lack of financial independence, lack of family support, poor financial conditions and lack of proper housing. In the following, each subtheme is discussed.

Lack of financial independence: Because of financial dependence, they could not meet the expenses of their lives without depending on others. They needed others to support them financially: “When I was a student, I wanted to get married. But besides my blindness, I didn’t have a job or a good source of income to lead an independent life. Therefore, I did not marry. There were a few girls I liked, but I didn’t propose to them and I didn’t even think about marriage. You should never get married when you don’t have a good job and income” (P 9).

Lack of family support: The family plays a vital role in marriage and spouse selection. The participants were upset that the family did not take action to achieve their happiness and marriage: “Family is very important. It would be great if they didn’t forget us. I don’t know why they wait and don’t do anything until our marriage age passes and we can no longer get married and find our favorite case” (P 10).

Poor economic conditions: Poor economic conditions can adversely affect choosing a spouse and starting a family. The participants pointed out that employment and meeting the basic needs are necessary to start a family: “Sometimes when we talk about marriage, people say that inflation and prices are too high and we can’t get married anymore. They talk about marriage expenses. For example, they say one should have 200 million Tomans (Iran currency) to pay for gold and jewelry and 500 million Tomans to pay for wedding costs” (P 6).

Lack of proper housing: Having a house is one of the most important things to start a family: “Because I didn’t have any income, I didn’t think about marriage at all, but with the help of my father, we did a few jobs, and I earned some money to buy a house and a car. Then, in 2021, I thought about getting married” (P 4).

Negative public stigma

This main theme consists of two subthemes: No need for blind people to get married and a parasitic lifestyle. In the following, each subtheme is discussed.

No need for blind people to get married: The participants believed that the main problem faced by blind people is that healthy people do not understand them and do not believe in their abilities to manage their lives: “Public awareness should be raised so that people come to the belief that marrying blind people is not so bad. They are also humans and have some skills. They should give blind people a chance” (P 7).

Parasitic lifestyle: Because people with VI have difficulty in doing their lives, others often think that they have a parasitic lifestyle; this view can be one of the obstacles to their marriage. The participants were worried that they would be a burden on their future spouses: “I am looking for an employed wife as she can help me in my life. If she is employed, I will have more job security (P 13).

Need for a mate

This main theme consisted of four subthemes: Finding a purpose in life, having a companion, escaping from loneliness, and satisfying sexual and emotional needs. In the following, each subtheme is discussed.

Finding a purpose in life: The participants were looking for a way to find a definite purpose to continue their lives. They wanted to experience self-confidence, motivation, and love for life; marriage was one of their most important goals. “A purpose gives meaning to my life. I didn’t have a plan for my life. If I get married, maybe I will have a plan for my life. I will find a job or pursue a business, I can live like other people” (P 1).

Having a companion: Persons with VI consider marriage a family foundation and an essential factor for the :union: and empathy of two people and the basis for their growth. The participants expressed that having a companion gives life meaning and saves a person from living aimlessly. “When you get married, you get peace of mind as there is someone who accepts you with all your problems and disabilities and you can choose someone that you love, and you will have a pleasant feeling” (P 14).

Escape from loneliness: The participants felt lonely due to the problems they faced in their marriage, which led to feelings of emptiness, rejection and unwantedness in them: “In my opinion, everyone needs a person to be by their side throughout their life, free them from loneliness and help them with their problems and life” (P 15).

Satisfying sexual and emotional needs: The participants believed that the best way to satisfy sexual instincts is to use natural ways based on the cultural norms of the society, and they felt that they could be satisfied through an emotional connection with the opposite sex: “It’s not just a sexual need. There are also emotional needs. Thus, you have someone who is waiting at home, loves you, and has prepared everything for you. And you can satisfy your need for sex with her” (P 10).

Discussion

The present study investigated the topic of marriage and love among blind and visually impaired men. The findings showed that blind and visually impaired men have negative and hopeless feelings towards spouse selection and marriage due to fear of rejection, feeling like a burden, feelings of anger and hatred, suspicion towards the future spouse, rejection by the future spouse, the birth of a blind child, extreme fear of accepting responsibility in life, feelings of despair and pessimism, and uncertainty about the future. In a similar vein, Satvat et al. (2018) examined the challenges of the marriage of physically disabled people. They found that these people have negative feelings and attitudes toward marriage and experience challenges such as feeling like a burden, running away from their current life, feeling ashamed, and not feeling happy because of celibacy, irrational and unrealistic expectations of marriage, inability to bear a child, and non-acceptance of physical conditions of people with physical disabilities.

One of the concerns of blind and visually-impaired people is the fear of not being accepted by their future life partner, which can be due to the problems caused by VI, making them unable to handle life affairs like their sighted counterparts. As a result, they suffer from low self-esteem and self-confidence. Docia and Silverstein (2020) reported increasing levels of depression and anxiety among people with VI. Döner (2015) also found that rejection by a potential partner due to VI or having concerns about the possibility of rejection was widespread among adults with visual disabilities.

The findings from the present study showed that visually impaired men feel that they have a parasitic lifestyle, so they can meet their needs by relying on their future spouse. This feeling is induced by the problems these people face in handling their life affairs and lack financial independence. Kapperman & Kelly, (2019) also showed that one of the spouse selection criteria for men with VI is the financial condition of their future spouse.

People with VI, like any other human beings, need to satisfy their sexual and emotional needs. Moreover, to fill their leisure time and escape loneliness, they need a permanent life partner who makes them strive harder to achieve their goals. Enoch et al. (2018) showed that various reasons cause disabled people to get married. These reasons range from caring for and supporting a life partner to fulfilling gender roles, being recognized in society, and wanting to become a parent. In addition, people with VI do not differ from sighted people in their preferences in choosing a spouse; the main problem is finding a life partner and having an intimate relationship (Fekler et al., 2020).

There is a common belief that disabled people, especially visually impaired persons, do not need to get married. This belief probably originates from the fact that VI or disability can be considered the only characteristic of a person without considering their other characteristics and skills. Visually impaired people pay the price of this attitude in society due to the limitations caused by their vision problems. In this way, it is thought that marriage and family formation are not necessary for these people, and blind and visually impaired people do not need to get married. Khodabakhshi-Koolaee & Amoogholi, (2024) reported a negative public attitude regarding the marriage of visually impaired people. They also showed that one of the challenges of marrying blind and partially sighted girls is the attitude that there is no need for blind people to marry. Enoch et al. (2018) showed that society has discriminated against people with disabilities throughout history, which affects their participation in society. This condition may negatively impact their lives by limiting and making it more difficult for them to participate in society. These people face many social and financial challenges in their marriages. Moreover, Döner (2015) showed that people with VI face various forms of discrimination concerning having sexual relations and finding a life partner, including prejudices, humiliation, and receiving worrying questions about VI and sexuality. All of these problems became barriers to starting and maintaining sexual relationships for people with VI. Even at the beginning of romantic relationships, which probably involved various aspects of sexual activities, the participants had difficulties due to public attitudes towards visual impairment, sexual desires and romantic relationships. Blind people look for a life partner to escape their loneliness. Anderson (2018) shows that disabled people experience higher social isolation, low self-esteem, and more depression than their non-disabled peers due to having less frequent social interactions.

Overall, the findings of the present study suggested that the emotional and psychological concerns and needs of men with VI concerning spouse selection are partially based on their lived experience as disabled persons, including their fear of finding a suitable spouse and worry about their future marital life. In addition, some of these concerns are rooted in negative public views, such as being a burden or not having the right to marry and start a family. Moreover, lacking employment and income adds to their concerns. However, their emotional, sexual and psychological needs to find a spouse are still there, not to mention social and family barriers to marriage. Rehabilitation programs for people with VI in Iran’s Welfare Organization system rely more on meeting immediate financial needs, such as subsidies or glasses and ophthalmologist visits to help these people. Meanwhile, the counseling rehabilitation needs of these people, including the need for independence, spouse selection, and having a job, are not addressed. The data in this study revealed the need to address the concerns and needs of people with VI in rehabilitation programs. In addition to genetic and medical counseling, developing counseling programs, psychological treatments and virtual and face-to-face databases is essential for people with VI to give them a chance to find a life partner.

The current research had some limitations. This descriptive phenomenological research was based on the lived experiences of the participants who lived in a specific cultural and social context (Arak City, Iran) and were members of the Iranian Blind Association, Arak City Branch. Therefore, the findings do not represent men’s lived experiences in the entire visually impaired population in Iran. However, most qualitative studies aim not to generalize but to provide a rich and contextual understanding of some aspect of the human experience through intensive study of a specific group.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that the spouse selection concerns of men with VI include adverse feelings and disappointment about marriage, lack of support and financial resources, negative public stigma and the need for a mate. Education, treatment, psychological rehabilitation, and building self-confidence are essential for blind and visually impaired people. Besides, raising public awareness can contribute to developing a new perspective on accepting disabled persons and planning their employment to meet their living costs. It is suggested that future studies explore the views and experiences of family members, such as parents and siblings of visually impaired people, regarding choosing a spouse. Also, conducting a grounded theory study can explore the process of selecting a spouse for the visually impaired. In addition, considering that VI prevents seeing the physical presence of the opposite sex, research on other mate selection criteria in visually impaired men (such as body odor, voice type and mental imagination of a life partner) can provide valuable data.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research (Code: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1401.254). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants for conducting and recording the interviews. The participants were also reassured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Alireza Malekitabar, approved by the Department of Counseling, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the officials of the Arak Welfare Organization and the participants who cooperated closely with them.

References

Anderson, R., 2018. Disabled and out? Social interaction barriers and mental health among older adults with physical disabilities [PhD dissertation]. Michigan: The University of Nebraska. [Link]

Aslan, U. B., Calik, B. B. & Kitiş, A., 2012. The effect of gender and level of vision on the physical activity level of children and adolescents with visual impairment. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(6), pp. 1799-804. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2012.05.005] [PMID]

Bhagchandani, B., 2014. The effect of visual disability on marital relationships [MA thesis]. Arizona: Arizona State University. [Link]

Braithwaite, S. R., Delevi, R. & Fincham, F. D., 2010. Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students. Personal Relationships, 17(1), pp. 1-12. [DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01248.x]

Chilwarwar, V. & Sriram, S., 2019. Exploring gender differences in choice of marriage partner among individuals with visual impairment. Sexuality and Disability, 37, pp. 123-39. [DOI:10.1007/s11195-018-9536-x]

Conroy-Beam, D. & Buss, D. M., 2016. Mate Preferences. In V. Weekes-Shackelford, T. Shackelford, & V. Weekes-Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science (pp. 1-11). Cham: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_1-1]

Dörfler, V. & Stierand, M., 2021. Bracketing: A phenomenological theory applied through transpersonal reflexivity. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 34(4), pp. 778-93. [DOI:10.1108/JOCM-12-2019-0393]

Döner, H., 2015. Sexual knowledge, sexual experiences and views on sexuality education among adults with visual disabilities [MA thesis]. Ankara: Middle East Technical University. [Link]

Docia, D. L.& Silverstein. S. M., 2020. Visual impairment and mental health: Unmet needs and treatment options. Clinical Ophthalmology,14, pp. 4229-51. [DOI:10.2147/OPTH.S258783] [PMID] [PMCID]

Enoch, A., et al., 2018. Expectations of and challenges in marriage among people with disabilities in the yendi municipality of Ghana. Developing Country Studies, 8(9), pp. 19-23. [Link]

Ezinne, N. E., et al., 2022. Visual impairment and blindness among patients at Nigeria Army Eye Centre, Bonny Cantonment Lagos, Nigeria. Healthcare, 10(11), pp. 2312. [PMID] [PMCID]

Fekler, O., Bokek-Cohen, Y. A. & Braw, Y., 2020. Are you seeing him/her? Mate choice in visually impaired and blind people. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 67(5), pp. 467-83. [DOI:10.1080/1034912X.2019.1617412]

Gordon, P. A., Tschopp, M. K. & Feldman, D., 2004. Addressing issues of sexuality with adolescents with disabilities. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 21, pp. 513-27. [DOI:10.1023/B:CASW.0000043362.62986.6f]

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2001). Guidelines and checklist for constructivist (aka fourth generation) evaluation. [Link]

Kapperman, G. & Kelly, S., 2019. Human mate selection theory (Specific considerations for persons with visual impairments). In: J. Ravenscroft (Ed), The Routledge Handbook of Visual Impairment (pp. 9). London: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9781315111353-21]

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A. & Amoogholi, Z., 2024. The psychosocial experiences of girls with visual impairment about the ideal spouse and marriage. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 42(2), pp. 312-24. [DOI:10.1177/02646196221124427]

Morrow, R., Rodriguez, A. & King, N., 2015. Colaizzi’s descriptive phenomenological method. The Psychologist, 28(8), pp. 643-4. [Link]

Otuka, O. A. I., et al., 2021. Prevalence and causes of low vision and blindness among adult patients attending eye clinic in a tertiary hospital in South East, Nigeria. Asian Journal of Medicine and Health, 19(8), pp. 20-8. [DOI:10.9734/ajmah/2021/v19i830353]

Pinquart, M. & Pfeiffer, J. P., 2011. Psychological well-being in visually impaired and unimpaired individuals: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 29(1), pp. 27-45. [DOI:10.1177/0264619610389572]

Praveena, K. R. & Sasikumar, S., 2021. Application of colaizzi’s method of data analysis in phenomenological research. Medico-legal Update, 21(2), pp. 914-8. [Link]

Satvat, A., et al., 2018. [Identifying the challenges of marriage of persons with physical/motor disabilities in Tehran: A Phenomenological Study (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Rehabilitation Research in Nursing (IJRN), 5(2), pp. 56-62. [Link]

Scheller, M., et al., 2021. The role of vision in the emergence of mate preferences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(8), pp. 3785-97. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-020-01901-w] [PMID] [PMCID]

Schulz, C. H., 2008. Collaboration in the marriage relationship among persons with disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly, 28 (1), pp. 1-10. [DOI:10.18061/dsq.v28i1.71]

Smith, D.W., 2020. Descriptive psychology and phenomenology: from brentano to husserl to the logic of consciousness. In: D. Fisette, G. Fréchette & F. Stadler (Eds), Franz brentano and austrian philosophy. Vienna circle institute yearbook, vol 24. Cham: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-40947-0_3]

State welfare Organizaon of Iran., 2023. [The population of the blind; 13.5% of disabled people in the country/facilitating employment conditions for the blind (Persian)]. Retrieved from: [Link]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2023/12/17 | Accepted: 2024/04/20 | Published: 2024/08/1

Received: 2023/12/17 | Accepted: 2024/04/20 | Published: 2024/08/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |