Sun, Feb 1, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 11, Issue 3 (Summer 2025)

JCCNC 2025, 11(3): 237-248 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Zebardast A, Nateghian N, Shakerinia I. The Effect of Mindfulness-based Self-compassion Training on Nurses’ Anger Management, Spiritual Well-being, and Job Involvement. JCCNC 2025; 11 (3) :237-248

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-589-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-589-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran. , zebardast@guilan.ac.ir

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 631 kb]

(1744 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1005 Views)

Nurses are exposed to stress in their workplace that can lead to aggressive behaviors and negatively impact their well-being and job satisfaction.

Self-compassion training can significantly reduce nurses’ anger by 33%.

Self-compassion training can significantly increase nurses’ spiritual well-being by 19%.

Self-compassion training can significantly increase nurses’ job involvement by 23%.

Self-compassion training can significantly reduce nurses’ anger by 33%.

Self-compassion training can significantly increase nurses’ spiritual well-being by 19%.

Self-compassion training can significantly increase nurses’ job involvement by 23%.

Plain Language Summary

Nurses are exposed to tension and stress in the workplace, which can lead to aggressive and violent behaviors and reduce the quality of patient care. Job involvement among nurses is also of great importance, as it significantly affects their job performance. Spiritual well-being is one of the factors affecting anger. Spirituality can have a significant effect on various aspects of care. In this regard, we assessed the impact of self-compassion training on anger management, spiritual well-being, and job involvement of nurses in Iran. Self-compassion training significantly decreased nurses’ anger and increased their spiritual well-being and job involvement. Therefore, health policymakers are advised to consider incorporating self-compassion training for all nurses to enhance healthcare quality.

Full-Text: (472 Views)

Introduction

Anger is triggered in various situations, such as imagined or real failures, humiliations, injuries, or injustices, and can cause involuntary responses, including increased heart rate and blood pressure, sweating, and elevated blood sugar levels (Baillie et al., 2009). The American Psychological Association (APA) has defined anger as a normal and useful emotion that can be destructive if it is out of control and affects interpersonal relationships (Huang et al., 2023). Anger, as a component of negative emotion, can be due to dropping out of school, delinquency, smoking and alcoholism, psychopathology, general health problems, low self-esteem, and various psychiatric disorders (Hyland et al, 2016; Quinn et al., 2014; Duncan et al., 2016). Also, anger is a negative emotion that is subjectively experienced as an arousing state of hostility towards someone or something as the source of a hateful event (Novaco, 2020). Its adverse effects on interpersonal behavior and the inner and psychological states of an individual have attracted the attention of researchers. Inability to control aggressive behavior, not only causes interpersonal problems and crime, delinquency, and violation of others’ rights but also can be internalized and cause various psychological and physical problems, such as depression, migraine headaches, and stomach ulcers (Asgari Tarazoj et al., 2018; Rahmani et al., 2020).

Nurses, due to their sensitive and stressful work environment, are exposed to many work emotions and tensions, leading to anger and violence (Asgari Tarazoj et al., 2018). The 2020 health and safety executive’s report ranks nursing among the top three most stressful professions in the United Kingdom (Health & Safety Executive, 2020). It is probably the most stressful profession among health professionals (Mirzaei et al., 2022). In addition to affecting the professional and personal lives of nurses, anger decreases the quality of care and work efficiency. However, it increases frequency of absences from the workplace, burnout, quitting the job, financial losses, the quality of life and morale, and emotional reactions, including self-blame, helplessness, sadness, fear, decrease in job satisfaction, alterations in relationships with family and colleagues, feelings of guilt and incompetence, and indirect and direct financial burden on the economy of health system and consequently the society (Mirzaee et al., 2014; Asgari Tarazoj et al. 2018). Although many measures and interventions have been provided by the guardians of healthcare worldwide regarding the control and containment of nurses’ anger, still one of the important challenges in nursing services is the high level of violence and anger among nurses, especially in outpatient treatment centers (Esmaeilpour et al., 2011; Khosravi et al., 2022).

Regarding the factors that affect anger, the cognitive, social, and individual characteristics of an individual should be taken into account (Yang et al., 2017). One of these characteristics is spiritual well-being, which is defined as a positive evaluation of life and a balance between positive and negative emotions. Spiritual well-being fosters balanced growth and health in a person, paving the way for the proper development of their talents. Individual growth and social development depend on how much spiritual well-being is valued. Individuals with high spirituality tend to experience more positive emotions. People with a low sense of well-being evaluate events as unfavorable and experience negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression (Village & Francis, 2023). Also, people with high spiritual intelligence have flexibility, self-awareness, a high mental capacity to face difficult situations, a capacity for inspiration and intuition, a mystical attitude to the universe, a tendency to search for answers to life’s fundamental questions, the capacity to think about existential issues, and the ability to understand spiritual matters. Spiritual intelligence enhances mental health by fostering a sense of sanctity and meaning in life, promoting a balanced understanding of the value of possessions, and guiding a mission toward life’s values and human well-being, as well as fostering hope for a better world (Fazeli Kebria et al., 2021). Recently, psychologists, sociologists, medical professionals, and nurses have found that spirituality can have a significant impact on various aspects of medical care (Ross et al., 2014). Previous studies have suggested a relationship between nurses’ spirituality and their provision of spiritual care to patients (Farahani Nia et al., 2006).

Since job involvement affects work performance, it is of great importance and has therefore been considered by organizations as a key motivational factor. According to Kanungo’s definition (1982), job involvement refers to the degree of psychological identification a person has with their job. Those with high job involvement exhibit a positive attitude at work, report satisfaction with their jobs, and express increased commitment to their colleagues and the organization (Manshadi, 2019; Patil & Mulimani, 2020). Individuals with high job involvement are less likely to quit their jobs and tend to stay with their respective organizations for a predictable future (Rabinowitz & Hall, 1997; Khandan et al., 2022).

Self-compassion is another effective factor in managing anger, which operates through coping and emotion-regulation styles (Wu & Zhang, 2023). Self-compassion is the ability to accept undesirable and negative aspects of life. It is a state of warmth and acceptance of aspects of one’s being or life that one does not like (Basharpoor & Ahmadi, 2020). Self-compassion comprised three main components: common humanity against isolation, self-kindness against self-judgment, and mindfulness against excessive identification. A balanced approach is needed to negative experiences; thus, negative thoughts and feelings are neither exaggerated nor suppressed (Cha et al., 2023). Self-compassion activates the self-soothing system, leading to a reduction in fear and withdrawal in individuals (Grummitt et al., 2023).

Self-compassion is also effective in reducing angry feelings, the physical tendency to become angry, the angry mood, the angry reaction, and the occurrence of internal and external anger, while increasing the level of emotion regulation in people. As a result, people experience stress with less intensity (Afshani & Abouee, 2018; Hosseinipoor & Fallah, 2019). Those with higher self-compassion levels have less tendency to suppress or ruminate thoughts. Self-compassion not only helps protect individuals from adverse mental states but also contributes to enhancing positive emotional experiences. While self-compassion is linked to positive emotions, it transcends merely being a positive mindset; it involves the capacity to acknowledge negative emotions in a non-judgmental manner, without suppressing or denying the negative aspects of one’s experiences (Neff, 2003; Sajjadian, 2018). Furthermore, self-compassion is closely connected to compassion for others, as individuals with high levels of self-compassion tend to resolve interpersonal conflicts by taking into account both their own needs and those of others (Neff, 2003; Salehi & Sajjadian, 2018). Consequently, one of the relatively recent approaches derived from third-wave psychotherapy aimed at alleviating psychological disorders is compassion-based training (Trindade et al, 2020). The nature of compassion is fundamental kindness, accompanied by a deep awareness of suffering and pain, along with a desire, motivation, commitment, and effort to relieve them (Grodin et al., 2019). This therapy emphasizes that the human mind reacts to both internal and external factors, and people should cultivate soothing thoughts and behaviors (Krieger et al., 2019). At the heart of compassion-based education is compassion-focused meditation, which is developed through the balance of three systems: the threat and self-protection system, the emotional system, and the social support system (Au et al., 2017). The goal of this educational approach is to teach essential strategies, including the rationale behind compassion, engaging in kind behaviors, cultivating compassionate imagery, and developing emotional awareness. It aims to enhance various aspects of compassion, psychological well-being, tolerance for discomfort, sensitivity, and empathy (Bluth & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2017).

Therefore, planning to ensure the mental health of nurses by paying attention to the role of positive psychological structures, such as anger management, spiritual well-being, and job conflict, seems important for the nurses’ job satisfaction. Considering the necessity and role of teaching self-compassion in the professional, personal, and family life of nurses, and because of the limited research on the relationship between self-compassion, anger management, spiritual well-being, and occupational conflict of nurses in Iran, we assessed the effectiveness of self-compassion training on anger management, spiritual well-being, and job involvement of nurses.

Materials and Methods

Design, setting, and sample

The statistical population of this quasi-experimental study, which employed a pre-test, post-test design with a control group, consisted of nurses working in various hospital departments affiliated with the universities of medical sciences in Rasht City, Iran, during the first 6 months of 2021. A total of 26 nurses were selected using the available sampling method. The inclusion criteria included a bachelor’s degree or higher in nursing, no prior participation in similar training sessions, and a minimum of 2 years of nursing work experience. Absence of two or more sessions, failure to complete the questionnaires, and no consent to continue participating in the study were the exclusion criteria.

To determine the sample size in each of the control and experimental groups, Cohen’s table of sample size (8-3-12) was used, based on the F-ratio of variance analysis (Cohen, 1988). The degree of freedom of the table was calculated according to the existence of two groups through the Equation 1:

1. Degree of freedom (U)=(K-1), U=(2-1)=1

The smallest sample size for the value of U is equal to 1. If we consider a 95% confidence level, the power of the test will be 0.50, and the effect size is 0.8. In this way, the research sample was calculated as 13 for each group (and 26 for both groups). The subjects were randomly assigned to the control and experimental groups using the lottery method.

Data collection

Data collection was conducted using the Buss-Perry aggression questionnaire (BPAQ), the Paloutzian and Ellison spiritual well-being scale (SWBS), and the Kanungo job involvement questionnaire (JIQ). A demographic questionnaire was also used to collect information on age, sex, education level, work experience, and shift work.

The BPAQ, designed by Buss & Perry (1992), measured the aggression of nurses. It is a 29-item self-report instrument with four subscales of hostility (8 items), physical aggression (9 items), anger (7 items), and verbal aggression (5 items). It is scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (extremely uncharacteristic) to 5 (extremely characteristic). Two items are reverse-scored, and higher total scores indicate a higher level of aggressive behavior.

The reliability of its Persian version has been confirmed by Bahrami et al. (2012), and its Cronbach α has been reported to be 0.89. Additionally, the test, re-test reliability is 0.78 for the whole scale, ranging from 0.61 to 0.74 for the subscales (Karimi et al., 2013). The Cronbach α coefficient for the whole instrument was 0.78 in our research.

The SWBS is a tool for self-assessing perceived spiritual well-being, created by Paloutzian and Ellison in 1982. It has 20 items and is scored on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely agree) to 6 (completely disagree) for negatively worded items and from 6 (completely disagree) to 1 (completely agree) for positively worded items. This scale measures spiritual well-being in two senses: religious and existential, each with 10 items and a score of 10-60. The total score of the SWBS ranges from 20 to 120. A score of 20 to 40 indicates a low level, a score of 41 to 99 indicates a moderate level, and a score of 100 to 120 indicates a high level of spiritual well-being. The SWBS is a reliable and valid instrument, with Cronbach’s α coefficients ranging from 0.89 to 0.94 (Bufford, 1991). We used its Persian version to measure the spiritual well-being of nurses. Rezaei et al. (2009) confirmed the validity of the Persian version of SWBQ and reported its Cronbach α coefficient as 0.82. In our study, the Cronbach α coefficient was 0.82. We used the whole score of the scale.

The JIQ is a 10-item measure of job involvement developed by Kanungo in 1982, scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 5 (completely agree) to 1 (completely disagree). The total score ranges from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater job involvement. The internal consistency and test, re-test reliability coefficients of this scale are α=0.87 and r=0.85, respectively (Kanungo, 1982). We used the Persian version of this tool to measure the job involvement of nurses. Zabani Shadabad et al. (2017) used the Persian version of this questionnaire with 350 university employees and reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.89. In our study, Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.83.

Intervention

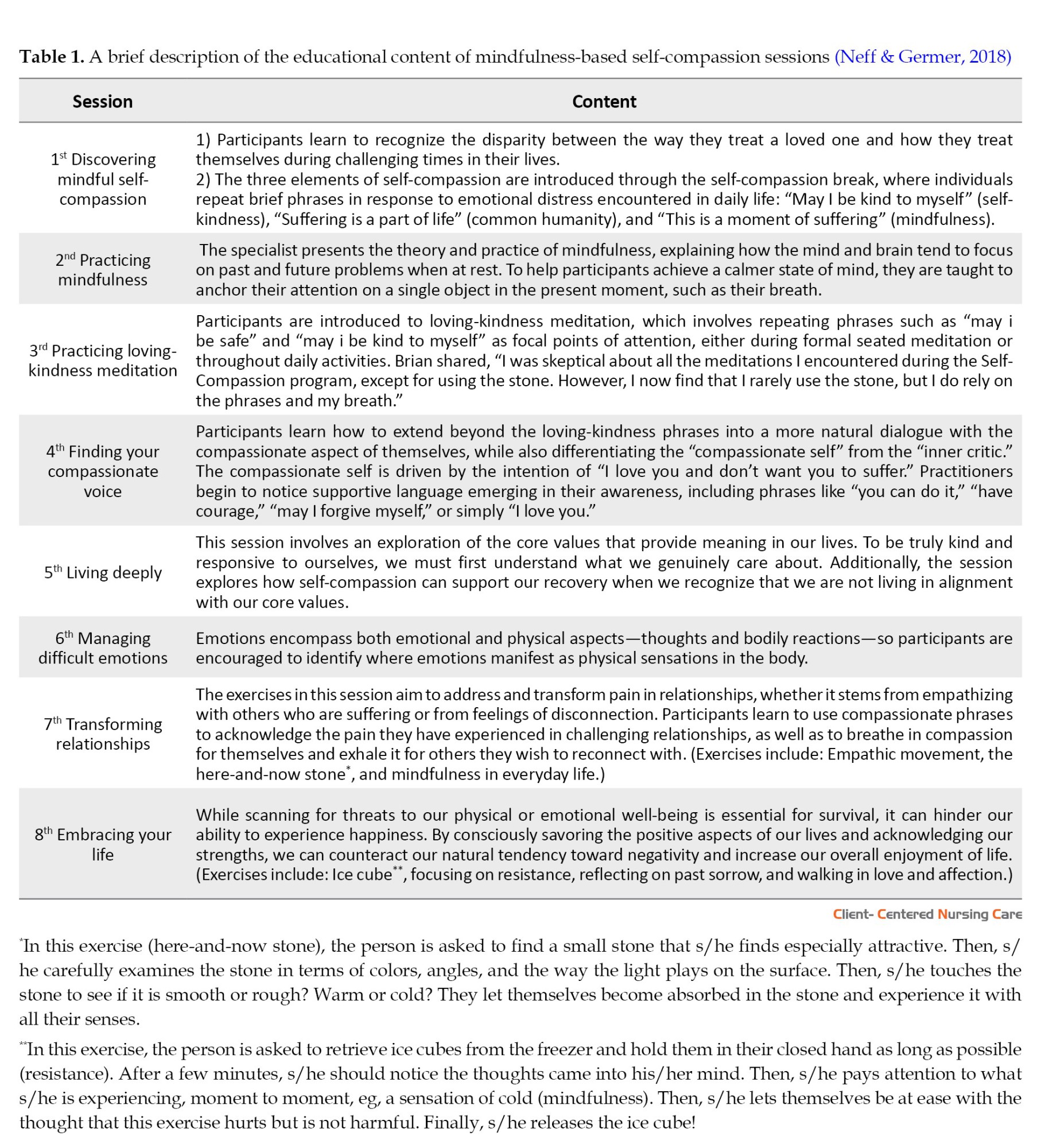

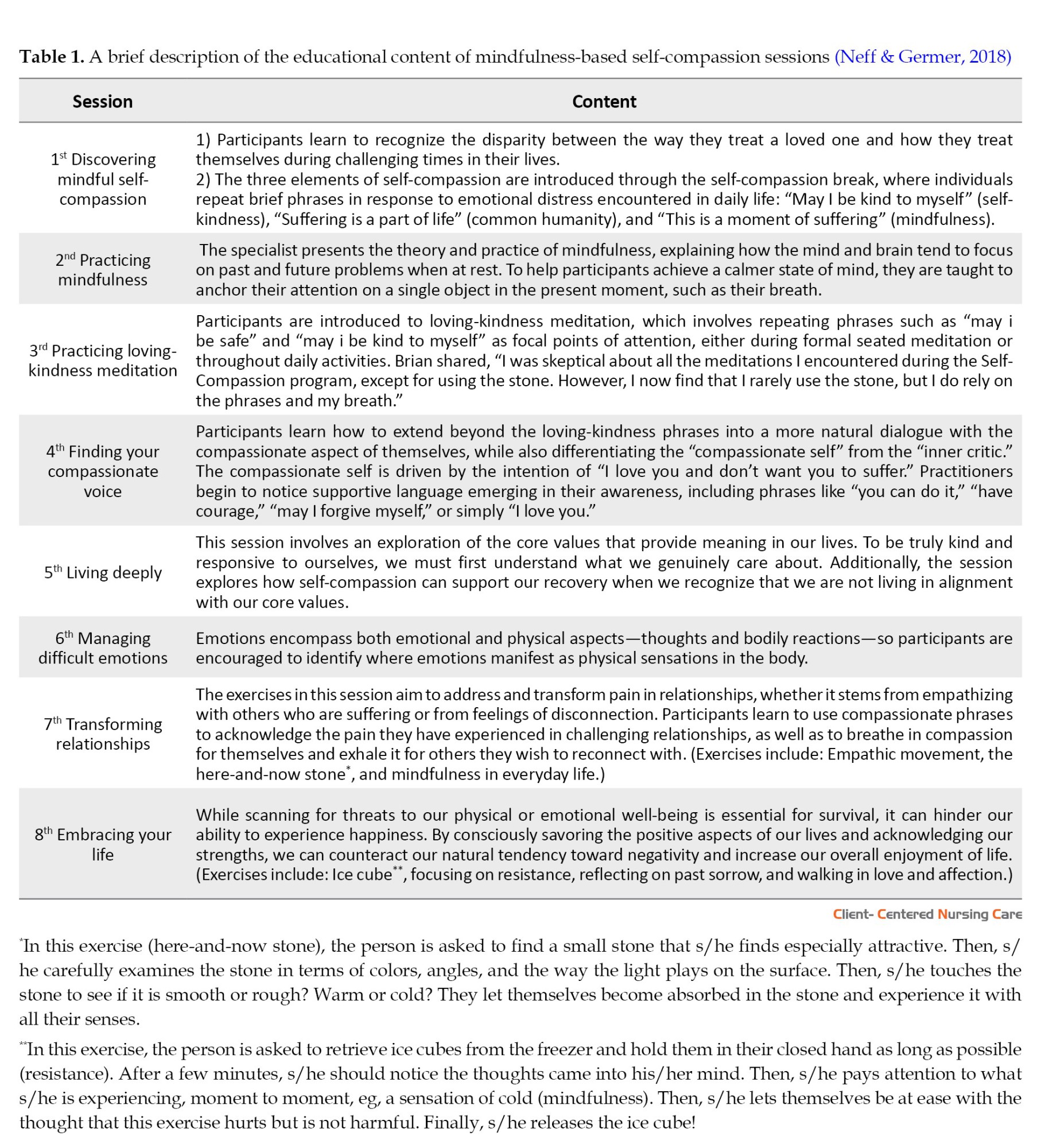

The experimental group underwent eight 90-minute sessions of compassion-based training, while the control group received no training. The intervention was conducted by a health psychology specialist, once a week for two months. Considering that this study coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic and preventive measures such as quarantine and social distancing were implemented, nurses could not be physically present in one location; therefore, virtual education was used. The education was presented using WhatsApp Messenger. The audio files of the sessions were also prepared and sent to the participants, along with their homework. At the beginning of each session, the educational materials covered in the previous session were reviewed, and homework was recapped. Nurses could discuss their questions with the health psychology expert or receive their homework training packages in the interval between the two sessions. The content of the intervention was adapted from Neff and Germer (2018) (Table 1).

Data analysis

Data analysis was done using multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) to investigate the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variables, and the paired t-test for within-group comparisons in the control and intervention groups at the pre-test and post-test phases, and the independent t-test for between-group comparisons at the pre-test and post-test phases. Frequency distribution, percentage, Mean±SD were also used. SPSS software, version 24 was used for the analysis. Before conducting MANCOVA, the assumptions were checked. According to the Shapiro-Wilk test results, the statistical distribution of the dependent variables was normal (P>0.05). The assumption of homogeneity of variances across various levels of the independent variables was accepted (P>0.05) using Levene’s test. Based on the F statistic value, the assumption of equality of regression coefficients in the groups was also accepted (P>0.05). Therefore, the assumptions of MANCOVA were established. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

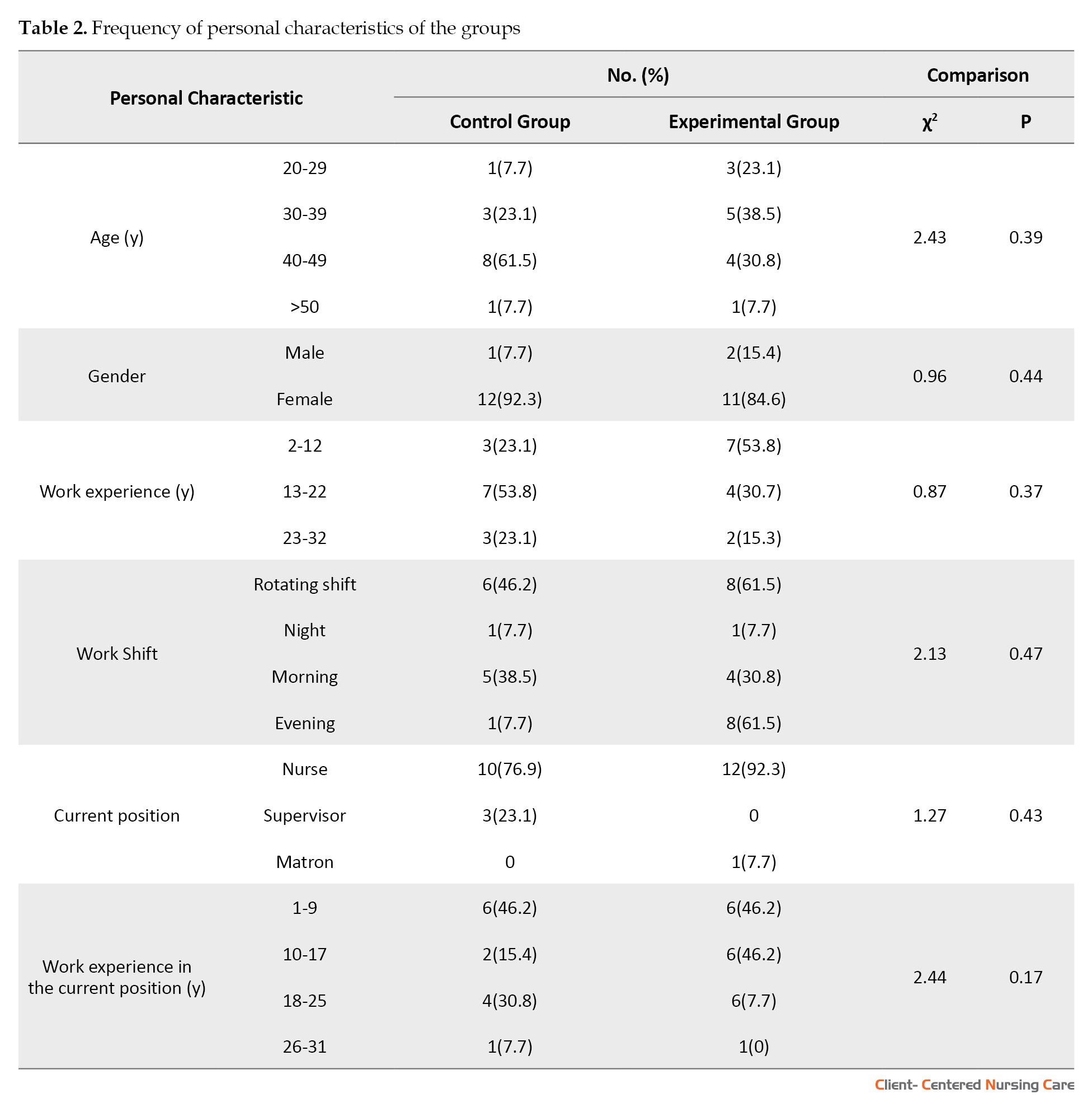

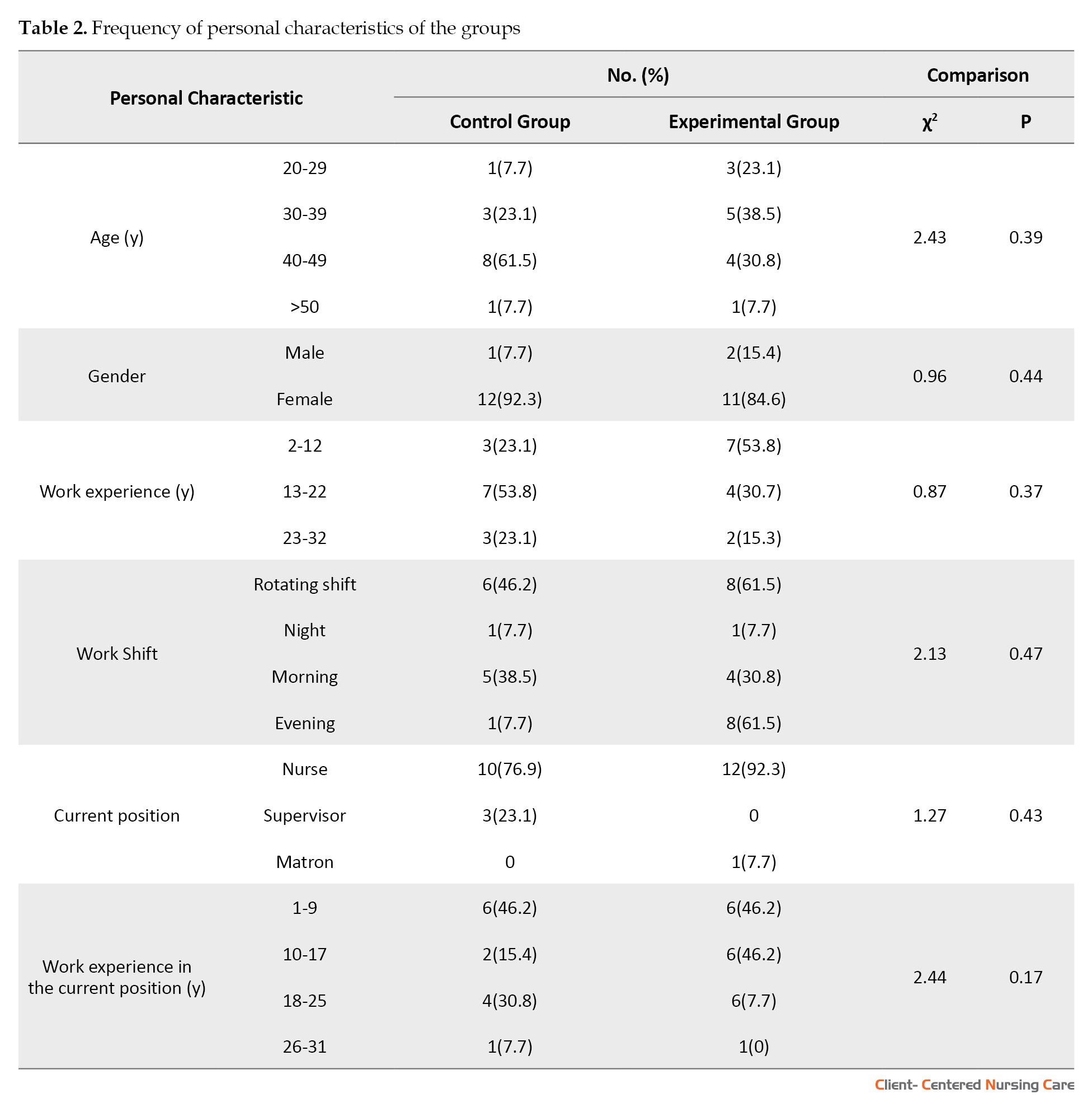

No significant difference was detected in personal characteristics between the two groups (Table 2).

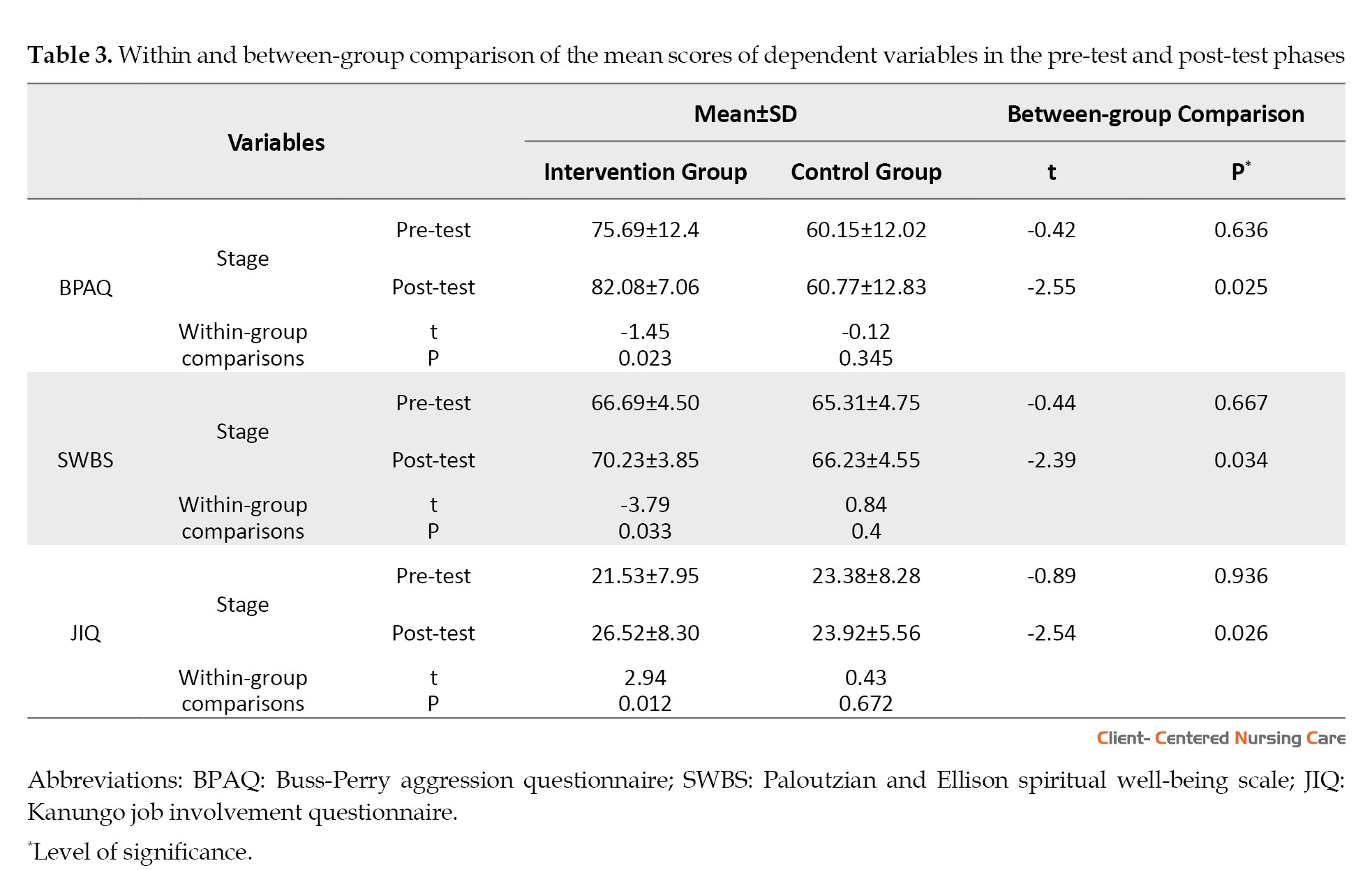

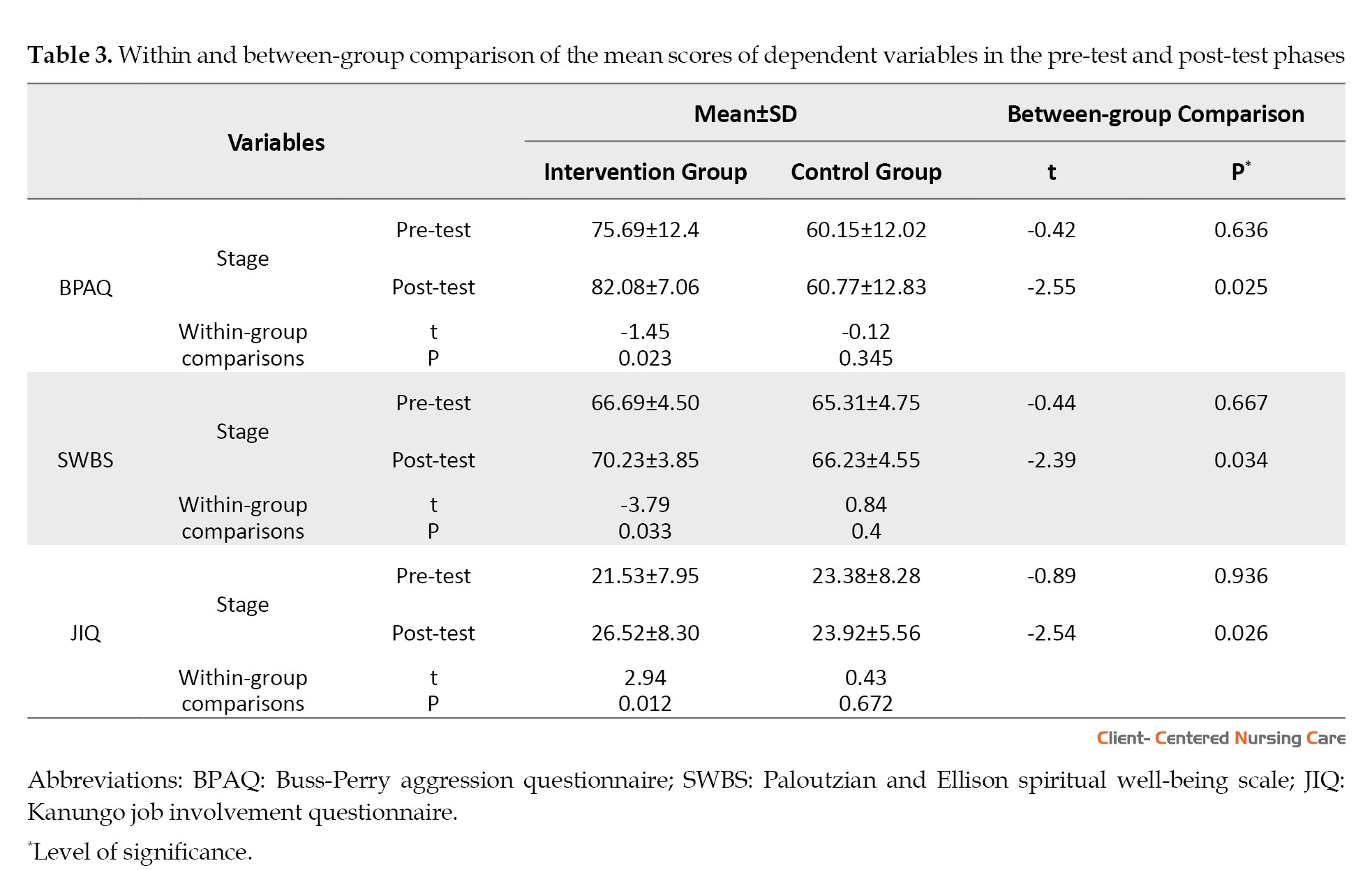

Within-group analyses using paired t-tests revealed that the post-test BPAQ score was significantly higher than the pre-test score in the intervention group (P=0.023). This difference was not significant in the control group (P=0.345). Similarly, the post-test SWBS score was significantly higher than the pre-test score in the intervention group (P=0.033), whereas no significant difference was observed in the control group (P=0.40). Additionally, the post-test JIQ score was significantly higher than the pre-test score in the intervention group (P=0.012), whereas this comparison was not significant in the control group (P=0.672) (Table 3).

Using an independent t-test, between-group comparisons revealed that the pre-test scores of BPAQ, SWBS, and JIQ were not statistically significant (P>0.05). Still, the difference in post-test scores was significant regarding BPAQ (P=0.025), SWBS (P=0.034), and JIQ (P=0.026) (Table 3).

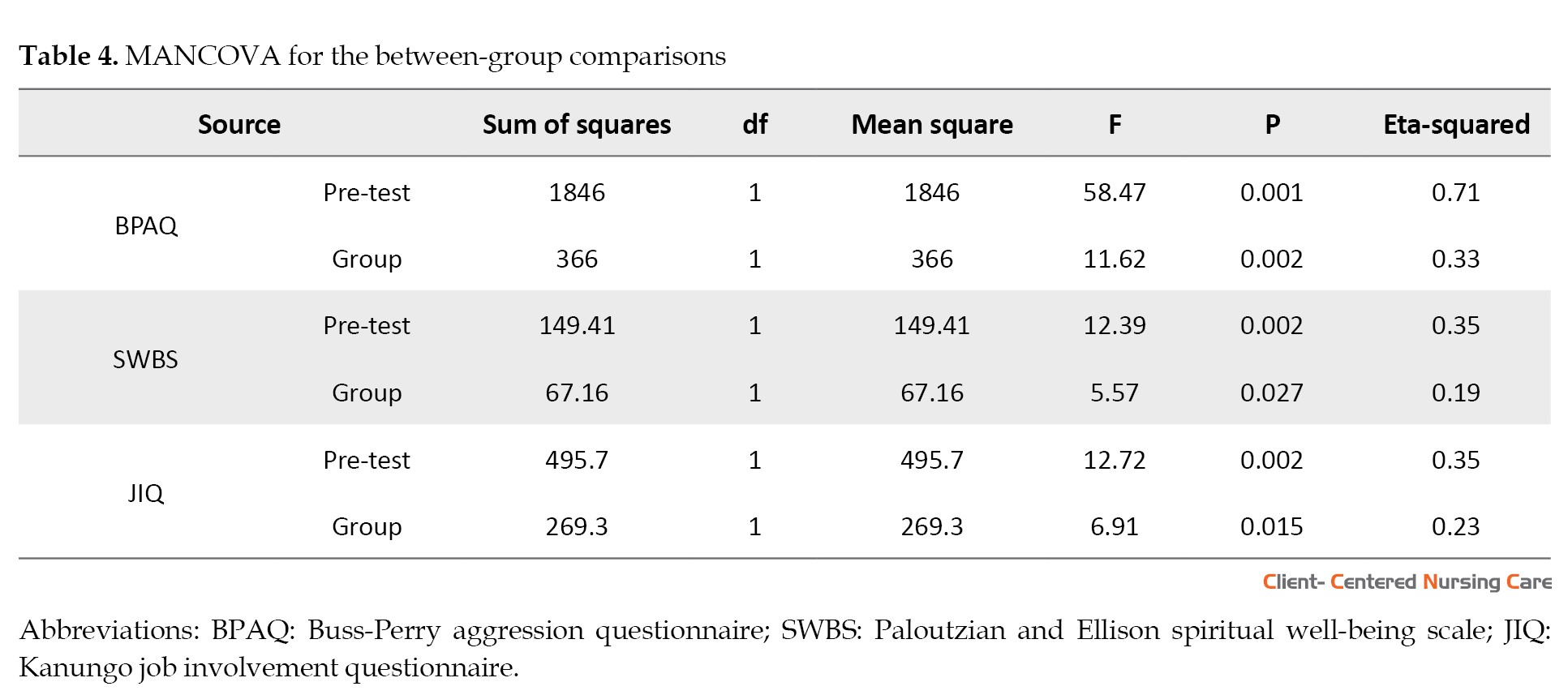

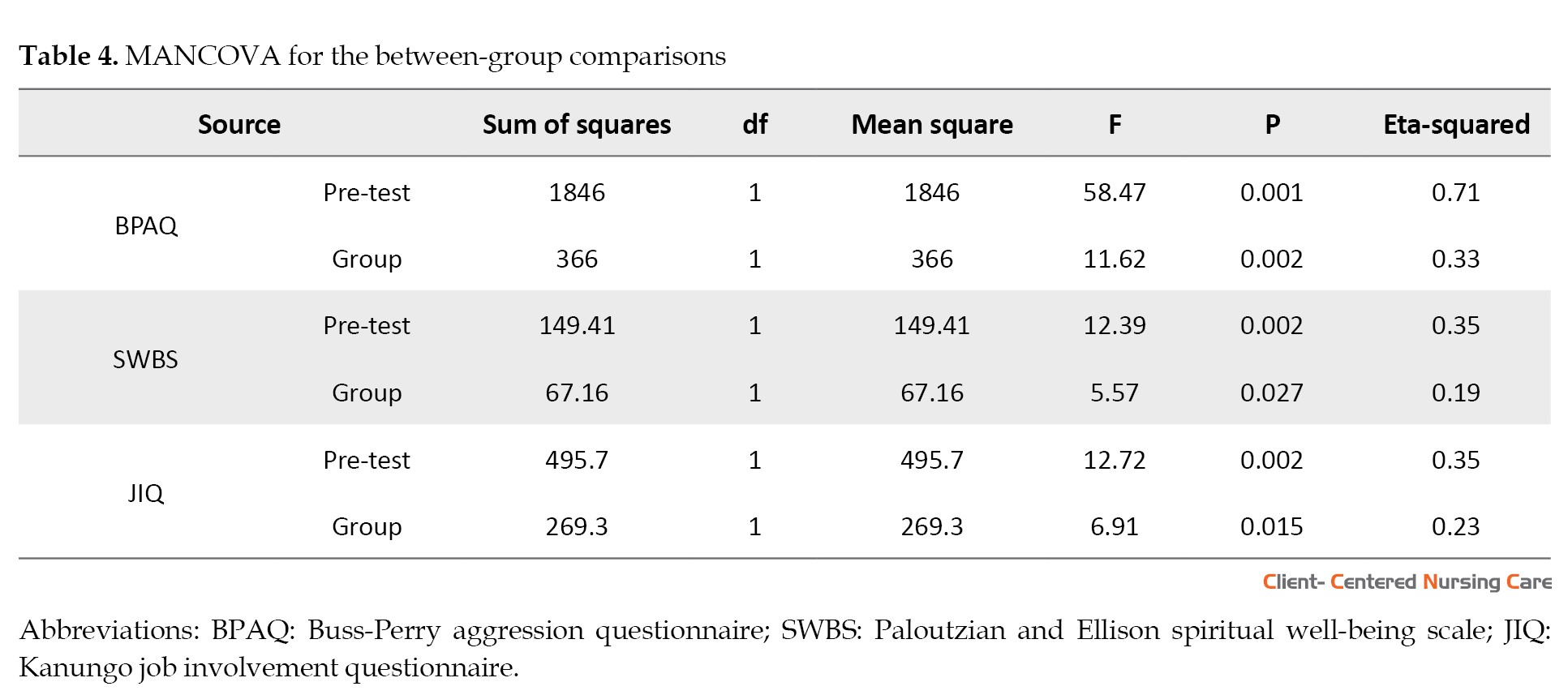

The results of the between-group comparisons for the BPAQ score (Table 4) showed that, after adjusting for the pre-test score, the post-test score was significantly different between the two groups (F=11.62, P=0.002).

Eta-squared=0.33, indicating that 33% of the improvement in nurses’ anger management was attributed to self-compassion training. Since the effect of the control variable (pre-test) was significant (P<0.001), the adjusted mean value was obtained by removing its impact from the main intervention. The adjusted mean score of BPAQ in the intervention group (79.36) improved compared to the control group (71.47).

The results of between-group comparisons for the SWBS score (Table 4) showed that, after adjusting for the pre-test score, the post-test score was significantly different between the two groups (F=5.57, P=0.027). Eta-squared=0.19, which shows that a 19% improvement in nurses’ spiritual well-being was due to self-compassion training. The adjusted mean score of SWBS in the intervention group (69.85) improved compared to the control group (66.60).

The results of the between-group comparisons for the JIQ score (Table 4) showed that, after adjusting for the pre-test score, the post-test score was significantly different between the two groups (F=6.91, P=0.015). Eta-squared was equal to 0.23, indicating that self-compassion training accounted for a 23% improvement in nurses’ job involvement. The adjusted mean score of JIQ in the intervention group (90.3) improved compared to the control group (83.8).

Discussion

This research investigated the effectiveness of self-compassion training on anger management, spiritual well-being, and job involvement of nurses working in Rasht hospitals. The protocol proposed by Neff and Germer (2018) was used to design the compassion-based education intervention. The results showed that self-compassion training markedly decreased nurses’ anger. The eta-squared value showed that a 33% improvement in nurses’ anger management was due to self-compassion training. In many cases, the angry mood and angry reaction are due to the surrounding people; using self-compassion training and emphasizing kindness and non-judgment, nurses realized that judging the behavior of the people around them led to the creation of such a mood and using the solutions presented in the treatment sessions, these reactions could be overcome. Additionally, self-compassion training reduced the physical tendency to anger, and by practicing compassionate speech, actions, and visualization, the subjects, who were nurses, could control their angry physical tendencies. The results mentioned above are in line with those of Naismith (2016), who investigated self-compassion/forgiveness interventions for anger and aggression in couples’ behavior, and Moradi (2022), who studied the effect of compassion techniques on anger and aggressive behaviors in mothers with mentally disabled children. They showed that compassion-focused therapy reduced anger and aggressive behaviors. Basharpoor and Ahmadi (2016) investigated the association between the dimensions of self-compassion and anger control and the prevalence of suicidal thoughts in people addicted to heroin. They reported that the prevalence of suicidal thoughts had a significant negative association with the level of mindfulness. Also, the prevalence of suicidal thoughts had a meaningful and positive relationship with isolation, excessive assimilation, self-judgment, internal and external anger, and angry tendencies. Teaching self-compassion is effective in controlling anger, as tolerance of distress is a key dimension of the compassion model.

Additionally, resilience and learning to use anger control require patience and tolerance of distress. These observations are consistent with our findings. Miyagawa and Taniguchi (2020) investigated the association between self-compassion and the way individuals experience unpleasant past-related events. They found that individuals with higher self-compassion experienced less anger when recalling past frustrating situations. Additionally, Darvei et al. (2019) reported that increasing self-compassion levels among nurses has a significant impact on stress reduction and job burnout.

Teaching self-compassion could increase the spiritual well-being of nurses. The eta-squared value showed that a 19% improvement in nurses’ spiritual well-being was due to self-compassion training. People who experience a greater search for the meaning of life are at a higher level of spiritual well-being and always experience positive emotions (e.g. joy, vitality, will), are more satisfied with life in the process of searching for meaning, and have a greater ability to endure stressful situations (Hooker et al., 2019).

Similarly, purposeful and hopeful thinking, along with familiarity with the necessary paths to achieve one’s goals, will lead to a deeper search for life’s meaning and greater inner satisfaction. Therefore, choosing appropriate goals and trying to achieve them can be called goal-oriented or optimistic thinking. If a person experiences satisfaction with life and more happiness, and only occasionally experiences emotions such as sadness and anger, they have high spiritual well-being. On the contrary, if they are dissatisfied with their life, they experience little happiness and interest, and continuously feel negative emotions, such as anger and anxiety, indicating low spiritual well-being (Hooker et al., 2019).

Jafari (2015) and Fazeli Kebria et al. (2021) demonstrated that individuals with high spiritual well-being tend to be satisfied with their family life, engage in favorable social interactions, have numerous friends, and experience fewer negative emotions. Based on Snyder’s theory of hope, having a hopeful mindset, sufficient resources for goal-oriented thinking, and familiarity with the necessary paths to achieve goals make life meaningful. In other words, an increase in hope leads to an increase in meaning, and an increase in meaning also causes an increase in hope or goal-oriented thinking. Based on the findings of this hypothesis and studies by Kazemi et al. (2019) and Mohamadian and Rasouli (2019), an increase in meaning leads to an increase in happiness, positive emotions, and life satisfaction and a reduction in both or one of these two lead to the rise in anxiety and depression. Similar to our results, Hashemi (2018) reported a positive effect of group self-compassion training on employees experiencing burnout.

Self-compassion training could increase nurses’ job involvement. The eta-squared value showed that a 23% improvement in nurses’ job involvement was due to self-compassion training. These findings support those of Rushforth et al. (2023), Darvei et al. (2019), and Khedmati (2020). Self-compassion enables individuals to care for themselves, cultivate awareness, and adopt a non-judgmental attitude towards their failures and inadequacies, ultimately accepting that their experiences are part of the normal human experience. Self-compassion serves as a construct that combines three key components: self-kindness versus self-judgment, mindfulness versus extreme assimilation, and human commonality versus isolation. The combination of these three components enables individuals to develop a perceptive system, after which they come to understand their nature, and based on this, they can exhibit appropriate reactions in times of crisis. Self-compassion serves as a mechanism by which people can identify and adjust their behavioral patterns in response to their environment. Compassion training enables individuals to be more receptive to others and accept them without prejudicial and negative judgments. It also encourages people to be kinder and more sensitive to the needs of others (Neff, 2003). Increasing the capacity of individuals in self-awareness, empathic concerns, and emotional regulation through mindfulness provides a step toward enhancing the communication capacity of nurses.

The limitations of using a self-report questionnaire in this study were unavoidable. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic’s occurrence during the study limited sample selection and the method of implementing the intervention. Given that most of the participating nurses were female, it is suggested that the effect of gender differences on the results be investigated and compared with our findings.

Conclusion

Eight sessions of self-compassion training can improve anger management, spiritual well-being, and occupational engagement of nurses. Therefore, it is suggested that health policymakers include self-compassion training for all nurses as part of their professional development to strengthen the healthcare system and promote the mental health, well-being, and job satisfaction of nurses in the face of job stress.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUILAN.REC.1400.007). Hospital approval was also obtained. After explaining the study objectives and methods to the participants and noting that their information would remain confidential, written informed consent was obtained from each of them.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, study design, review, and editing: Azra Zebardast; Supervision: Iraj Shakerinia; Investigation, analysis, and writing the original draft: Nima Nateghian; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the cooperation of the participants.

References

Afshani, S. A. & Abou’ee, A., 2019. [The effectiveness of self-compassion training in students’ anger control (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Family and Research, 16(3), pp. 103-24. [Link]

Asgari Tarazoj, A., Ali Mohammadzadeh, K. & Hejazi, S., 2018. [Relationship between moral intelligence and anger among nurses in emergency units of hospitals affiliated to Kashan University of Medical Sciences (Persian)]. Journal of Health & Care, 19 (4), pp. 262-71. [Link]

Au, T. M., et al., 2017. Compassion-based therapy for trauma-related shame and posttraumatic stress: Initial evaluation using a multiple baseline design. Behavior Therapy, 48(2), pp. 207-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.012] [PMID]

Bahrami, M. A., et al., 2012. [Moral intelligence status of the faculty members and staff of the Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences of Yazd (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, 5(6), pp. 81-95. [Link]

Baillie, L., et al., 2009. Nurses’ views on dignity in care. Nursing Older People, 21(8), pp. 22-9. [DOI:10.7748/nop2009.10.21.8.22.c7280] [PMID]

Basharpoor, S., Daneshvar, S. & Noori, H., 2016. The relation of self-compassion and anger control dimensions with suicide ideation in university students. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors and Addiction, 5(4), pp. e26165. [DOI:10.5812/ijhrba.26165]

Basharpoor, S. & Ahmadi, S., 2020. [Modelling structural relations of craving based on sensitivity to reinforcement, distress tolerance and self-Compassion with the mediating role of self-efficacy for quitting (Persian)]. Research on Addiction, 13(54), pp. 245-64. [Link]

Bluth, K. & Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A., 2017. Response to a mindful self-compassion intervention in teens: A within-person association of mindfulness, self-compassion, and emotional well-being outcomes. Journal of Adolescence, 57, pp. 108-18. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.04.001] [PMID]

Bufford, R. K., et ak, 1991. Norms for the spiritual weil-being scale. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 19(1), pp. 56-70. [DOI:10.1177/009164719101900106]

Buss, A. H. & Perry, M., 1992. The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), pp. 452-9. [DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452] [PMID]

Cha, J. E., et al., 2023. What do (and don’t) we know about self-compassion? Trends and issues in theory. Mechanisms, and Outcomes. Mindfulness, 14, pp. 2657-69. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-023-02222-4]

Cohen, J., 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. [Link]

Darvehi, F. , et al., 2019. [The impact of mindful self-compassion on aspects of professional quality of life among nurses (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology Studies, 10(34), pp. 89-108. [DOI:10.22054/jcps.2019.33577.1895]

Duncan, S. M., et al., 2016. Nurses’ experience of violence in Alberta and British Columbia hospitals. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive, 32(4), pp. 57-78. [Link]

Esmaeilpour, M., Salsali, M. & Ahmadi, F., 2011. Workplace violence against Iranian nurses working in emergency departments. International Nursing Review, 58(1), pp. 130-7. [DOI:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00834.x] [PMID]

Farahani Nia, M., et al., 2006. [Nursing students’ spiritual well-being and their perspectives towards spirituality and spiritual care perspectives (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Nursing, 18 (44), pp. 7-14. [Link]

Grodin, J., et al., 2019. Compassion focused therapy for anger: A pilot study of a group intervention for veterans with PTSD. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 13, pp. 27-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.06.004]

Hashemi, S. A, 2018. [The effectiveness of self-compassion training on burnout and job satisfaction of teachers (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Models and Methods, 9(31), pp. 25-46. [Link]

Health and Safety Executive., 2020. Work-related stress, anxiety or depression statistics in Great Britain, 2020. Merseyside: Health and Safety Executive. [Link]

Hooker , S. A., et al, 2019. Engaging in personally meaningful activities is associated with meaning salience and psychological well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(6), pp. 821-31. [DOI:10.1080/17439760.2019.1651895]

Hyland, S., Watts, J. & Fry, M., 2016. Rates of workplace aggression in the emergency department and nurses’ perceptions of this challenging behaviour: A multimethod study. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal, 19(3), pp. 143-48. [DOI:10.1016/j.aenj.2016.05.002] [PMID]

Hosseinipoor, Z. & Fallah, M., 2019. [The effectiveness of compassion training on communication skills and controlling the anger of the disciplines of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences in Yazd (Paersian)]. Paper presented at: The first conference on psychology, counseling and behavioral science, Tehran, Iran, 13 June 2019. [Link]

Huang, L. S., Molenberghs, P. & Mussap, A. J., 2023. Cognitive distortions mediate relationships between early maladaptive schemas and aggression in women and men. Aggressive Behavior, 49(4), pp. 418–30. [DOI:10.1002/ab.22083] [PMID]

Jafari, E., 2015. [Spiritual predictors of mental health in nurses: The meaning in life, religious well-being and existential well-being (Persian)]. Nursing and Midwifery Journal, 13(8), pp. 676-84. [Link]

Kanungo, R., 1982. Measurement of job and work involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(3), pp. 341-9. [DOI:10.1037//0021-9010.67.3.341]

Karimi, H., et al., 2013. [Comparing the effectiveness of group anger management and communication skills training on aggression of marijuana addicted prisoners (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Behavioural Sciences, 11(2), pp. 129-38. [Link]

Kazemi, Z., et al., 2019. [Study on the effect of spiritual well- being on the self- esteem and happiness of student –teachers (teacher training university in Gorgan-1396) (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi, 7(12), pp. 115-28. [Link]

Fazeli Kebria, M., Yadollahpour, M. H. & Gholinia Ahangar, H., 2021. [Relationship between spiritual intelligence and general health with the mediating role of spiritual well-being among university students (Persian)]. Journal of Religion and Health, 9(1), pp. 37-45. [Link]

Khandan, V., Hosseinzade, S. & Akbarpoor, T., 2022. [Examining the importance of job involvement in organizations (Persian)]. Paper presented at: 8th International Conference on New Perspective in Management, Accounting and Entrepreneurship, Tehran, Iran, 21 December 2022. [Link]

Khedmati, N., 2020. [The role of self-compassion and psychological flexibility in predicting the burnout of nurses (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi, 9(1), pp. 73-80. [Link]

Khosravi, S., et al., 2022. [The relationship between spiritual intelligence and anger in nurses working in emergency Departments of Educational Medical centers affiliated to the Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, 2021 (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research, 16(6), pp. 55-63. [Link]

Krieger, T., et al., 2019. An internetbased compassion-focused intervention for increased self-criticism: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 50(2), pp. 430-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2018.08.003] [PMID]

Grummitt L., et al., 2023. Self-compassion and avoidant coping as mediators of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mental health and alcohol use in young adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 106534. Advance online publication. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106534] [PMID]

Manshadi, M., 2019. The relationship between job involvement with organizational learning and organizational lnnovation among public school principals of meybod city. Journal of School Administration, 6(2), pp. 188-210. [Link]

Miyagawa, Y. & Taniguchi, J., 2020. Self-compassion and time perception of past negative events. Mindfulness, 11(2), pp. 746-55. [Link]

Mirzaee, R., Raesi, Z. & Kazemi, H., 2014. [The effectiveness of anger management and problem solving training on reduction of depression in prisoners (Persian)]. Sadra Medical Sciences Journal, 2(1) pp. 55-63. [Link]

Mirzaee, S., et al., 2022. [Effect of spiritual self-care education on the resilience of nurses working in the intensive care units dedicated to covid-19 patients in Iran (Persian)]. Complementary Medicine Journal, 12(2), pp. 188-201. [DOI:10.32598/CMJA.12.2.1166.1]

Mohamadian, R. & Rasoli, N., 2019. [Investigating the effect of spiritual well-being on the lifestyle of veterans with the role of happiness (case study: veterans of Rashtkhwar city) (Persian)]. Paper presented at: The 5th International Conference on Advanced Research Achievements in Social Sciences, Psychology and Psychology, Tehran, Iran, 21 September 2019. [Link]

Moradi, N., 2022. [The effectiveness of compassion therapy on resilience, emotional self-control and anger in mothers with mentally retarded children (Persian)]. Journal of New Developments In Psychology, Educational Sciences and Education, 5(52), pp. 61-75. [Link]

Naismith, I., 2016. “Barriers to compassionate imagery generation in personality disorder: Intra- and inter-personal factors [PhD dissertation]. London: UCL (University College London). [Link]

Neff, K. D., 2003. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), pp. 223-50. [DOI:10.1080/15298860309027]

Neff, K. & Germer, C., 2018. The mindful self-compassion workbook: a proven way to accept yourself, Build Inner Strenght, and Thrive. New York: Giuilford Press. [Link]

Novaco, R., 2020. Anger. In: V. Zeigler-Hill &T. K. Shackelford (Eds), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Cham; Springer. [Link]

Patil, M. R. & Mulimani, C. F., 2020. Improving Police Efficiency. Our Heritage, 68(1), pp. 813- 9. [Link]

Quinn, C. A., Rollock, D. & Vrana, S. R., 2014. A test of Spielberger’s state-trait theory of anger with adolescents: Five hypotheses. Emotion, 14(1), pp. 74-84. [DOI:10.1037/a0034031] [PMID]

Rabinowitz, S. & Hall, D. T., 1977. Organizational research on job involvemen. Psychological Bulletin, 84(2), pp. 265. [DOI:10.1037//0033-2909.84.2.265]

Rahmani, S., et al., 2020. [The effectiveness of self-compassion therapy on cognitive emotion regulation strategies and anxiety sensitivity in female nurses (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing (IJPN) Original Article, 8(4), pp. 99-110. [Link]

Rezaei, M., Seyed Fatemi, N. & Hosseini, F., 2009. [Spiritual well-being in cancer patients who undergo chemotherapy (Persian)]. Journal of Hayat, 14 (4 and 3), pp. 33-9. [Link]

Ross, L., et al., 2014. Student nurses perceptions of spirituality and competence in delivering spiritual care: A European pilot study. Nurse Education Today, 34(5), pp. 697-702. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2013.09.014] [PMID]

Rushforth, A., et al., 2023. Self-compassion interventions to target secondary traumatic stress in healthcare workers: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), pp. 6109. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph20126109] [PMID]

Razvani, M. & Sajjadian, I., 2018. [The mediatoring role of self compassion in the effect of personality traits on positive psychological functions among female university students (Persian)]. Positive Psychology Research, 4(3), pp. 13-28. [DOI:10.22108/ppls.2018.105034.1222]

Salehi, S. & Sajjadian, I., 2018. [The relation between Self-compassion with Intensity, Catastrophizig, and Self-efficacy of Pain and affect in Women with Musculoskeletal Pain (Persian)]. Journal of Anaesthesia and Pain, 8(2), pp. 72-83. [Link]

Trindade, I. A., Ferreira, C. & Pinto-Gouveia, J., 2020. Acceptability and preliminary test of efficacy of the Mind program in women with breast cancer: An acceptance, mindfulness, and compassion based intervention. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, pp. 162-71. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.12.005]

Village, A. & Francis, L.J., 2023. The effects of spiritual well-being on self-perceived health changes among members of the church of england during the covid-19 pandemic in England. Journal of Religion and Health, 62, pp. 2899-915. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-023-01790-y] [PMID]

Wu, Q. & Zhang, T. M., 2023. Association between self-compassion and cyber aggression in the COVID-19 context: Roles of attribution and public stigma. BMC Psychology, 11(1) pp. 66. [DOI:10.1186/s40359-023-01100-x] [PMID]

Yang, B. X., et al., 2017. Incidence, type, related Factors, and effect of workplace violence on mental health nurses: a cross-sectional survey. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32(1), pp. 31–8. [DOI:10.1016/j.apnu.2017.09.013] [PMID]

Zabani Shadabad, M. A., Hassani M. & Ghasemzade, A., 2017. [The relationship between Job engagement & job propriety with professional ethics & intent to leave (Persian)]. Ethics in Science and Technology, 12(2) pp. 77-84. [Link]

Anger is triggered in various situations, such as imagined or real failures, humiliations, injuries, or injustices, and can cause involuntary responses, including increased heart rate and blood pressure, sweating, and elevated blood sugar levels (Baillie et al., 2009). The American Psychological Association (APA) has defined anger as a normal and useful emotion that can be destructive if it is out of control and affects interpersonal relationships (Huang et al., 2023). Anger, as a component of negative emotion, can be due to dropping out of school, delinquency, smoking and alcoholism, psychopathology, general health problems, low self-esteem, and various psychiatric disorders (Hyland et al, 2016; Quinn et al., 2014; Duncan et al., 2016). Also, anger is a negative emotion that is subjectively experienced as an arousing state of hostility towards someone or something as the source of a hateful event (Novaco, 2020). Its adverse effects on interpersonal behavior and the inner and psychological states of an individual have attracted the attention of researchers. Inability to control aggressive behavior, not only causes interpersonal problems and crime, delinquency, and violation of others’ rights but also can be internalized and cause various psychological and physical problems, such as depression, migraine headaches, and stomach ulcers (Asgari Tarazoj et al., 2018; Rahmani et al., 2020).

Nurses, due to their sensitive and stressful work environment, are exposed to many work emotions and tensions, leading to anger and violence (Asgari Tarazoj et al., 2018). The 2020 health and safety executive’s report ranks nursing among the top three most stressful professions in the United Kingdom (Health & Safety Executive, 2020). It is probably the most stressful profession among health professionals (Mirzaei et al., 2022). In addition to affecting the professional and personal lives of nurses, anger decreases the quality of care and work efficiency. However, it increases frequency of absences from the workplace, burnout, quitting the job, financial losses, the quality of life and morale, and emotional reactions, including self-blame, helplessness, sadness, fear, decrease in job satisfaction, alterations in relationships with family and colleagues, feelings of guilt and incompetence, and indirect and direct financial burden on the economy of health system and consequently the society (Mirzaee et al., 2014; Asgari Tarazoj et al. 2018). Although many measures and interventions have been provided by the guardians of healthcare worldwide regarding the control and containment of nurses’ anger, still one of the important challenges in nursing services is the high level of violence and anger among nurses, especially in outpatient treatment centers (Esmaeilpour et al., 2011; Khosravi et al., 2022).

Regarding the factors that affect anger, the cognitive, social, and individual characteristics of an individual should be taken into account (Yang et al., 2017). One of these characteristics is spiritual well-being, which is defined as a positive evaluation of life and a balance between positive and negative emotions. Spiritual well-being fosters balanced growth and health in a person, paving the way for the proper development of their talents. Individual growth and social development depend on how much spiritual well-being is valued. Individuals with high spirituality tend to experience more positive emotions. People with a low sense of well-being evaluate events as unfavorable and experience negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression (Village & Francis, 2023). Also, people with high spiritual intelligence have flexibility, self-awareness, a high mental capacity to face difficult situations, a capacity for inspiration and intuition, a mystical attitude to the universe, a tendency to search for answers to life’s fundamental questions, the capacity to think about existential issues, and the ability to understand spiritual matters. Spiritual intelligence enhances mental health by fostering a sense of sanctity and meaning in life, promoting a balanced understanding of the value of possessions, and guiding a mission toward life’s values and human well-being, as well as fostering hope for a better world (Fazeli Kebria et al., 2021). Recently, psychologists, sociologists, medical professionals, and nurses have found that spirituality can have a significant impact on various aspects of medical care (Ross et al., 2014). Previous studies have suggested a relationship between nurses’ spirituality and their provision of spiritual care to patients (Farahani Nia et al., 2006).

Since job involvement affects work performance, it is of great importance and has therefore been considered by organizations as a key motivational factor. According to Kanungo’s definition (1982), job involvement refers to the degree of psychological identification a person has with their job. Those with high job involvement exhibit a positive attitude at work, report satisfaction with their jobs, and express increased commitment to their colleagues and the organization (Manshadi, 2019; Patil & Mulimani, 2020). Individuals with high job involvement are less likely to quit their jobs and tend to stay with their respective organizations for a predictable future (Rabinowitz & Hall, 1997; Khandan et al., 2022).

Self-compassion is another effective factor in managing anger, which operates through coping and emotion-regulation styles (Wu & Zhang, 2023). Self-compassion is the ability to accept undesirable and negative aspects of life. It is a state of warmth and acceptance of aspects of one’s being or life that one does not like (Basharpoor & Ahmadi, 2020). Self-compassion comprised three main components: common humanity against isolation, self-kindness against self-judgment, and mindfulness against excessive identification. A balanced approach is needed to negative experiences; thus, negative thoughts and feelings are neither exaggerated nor suppressed (Cha et al., 2023). Self-compassion activates the self-soothing system, leading to a reduction in fear and withdrawal in individuals (Grummitt et al., 2023).

Self-compassion is also effective in reducing angry feelings, the physical tendency to become angry, the angry mood, the angry reaction, and the occurrence of internal and external anger, while increasing the level of emotion regulation in people. As a result, people experience stress with less intensity (Afshani & Abouee, 2018; Hosseinipoor & Fallah, 2019). Those with higher self-compassion levels have less tendency to suppress or ruminate thoughts. Self-compassion not only helps protect individuals from adverse mental states but also contributes to enhancing positive emotional experiences. While self-compassion is linked to positive emotions, it transcends merely being a positive mindset; it involves the capacity to acknowledge negative emotions in a non-judgmental manner, without suppressing or denying the negative aspects of one’s experiences (Neff, 2003; Sajjadian, 2018). Furthermore, self-compassion is closely connected to compassion for others, as individuals with high levels of self-compassion tend to resolve interpersonal conflicts by taking into account both their own needs and those of others (Neff, 2003; Salehi & Sajjadian, 2018). Consequently, one of the relatively recent approaches derived from third-wave psychotherapy aimed at alleviating psychological disorders is compassion-based training (Trindade et al, 2020). The nature of compassion is fundamental kindness, accompanied by a deep awareness of suffering and pain, along with a desire, motivation, commitment, and effort to relieve them (Grodin et al., 2019). This therapy emphasizes that the human mind reacts to both internal and external factors, and people should cultivate soothing thoughts and behaviors (Krieger et al., 2019). At the heart of compassion-based education is compassion-focused meditation, which is developed through the balance of three systems: the threat and self-protection system, the emotional system, and the social support system (Au et al., 2017). The goal of this educational approach is to teach essential strategies, including the rationale behind compassion, engaging in kind behaviors, cultivating compassionate imagery, and developing emotional awareness. It aims to enhance various aspects of compassion, psychological well-being, tolerance for discomfort, sensitivity, and empathy (Bluth & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2017).

Therefore, planning to ensure the mental health of nurses by paying attention to the role of positive psychological structures, such as anger management, spiritual well-being, and job conflict, seems important for the nurses’ job satisfaction. Considering the necessity and role of teaching self-compassion in the professional, personal, and family life of nurses, and because of the limited research on the relationship between self-compassion, anger management, spiritual well-being, and occupational conflict of nurses in Iran, we assessed the effectiveness of self-compassion training on anger management, spiritual well-being, and job involvement of nurses.

Materials and Methods

Design, setting, and sample

The statistical population of this quasi-experimental study, which employed a pre-test, post-test design with a control group, consisted of nurses working in various hospital departments affiliated with the universities of medical sciences in Rasht City, Iran, during the first 6 months of 2021. A total of 26 nurses were selected using the available sampling method. The inclusion criteria included a bachelor’s degree or higher in nursing, no prior participation in similar training sessions, and a minimum of 2 years of nursing work experience. Absence of two or more sessions, failure to complete the questionnaires, and no consent to continue participating in the study were the exclusion criteria.

To determine the sample size in each of the control and experimental groups, Cohen’s table of sample size (8-3-12) was used, based on the F-ratio of variance analysis (Cohen, 1988). The degree of freedom of the table was calculated according to the existence of two groups through the Equation 1:

1. Degree of freedom (U)=(K-1), U=(2-1)=1

The smallest sample size for the value of U is equal to 1. If we consider a 95% confidence level, the power of the test will be 0.50, and the effect size is 0.8. In this way, the research sample was calculated as 13 for each group (and 26 for both groups). The subjects were randomly assigned to the control and experimental groups using the lottery method.

Data collection

Data collection was conducted using the Buss-Perry aggression questionnaire (BPAQ), the Paloutzian and Ellison spiritual well-being scale (SWBS), and the Kanungo job involvement questionnaire (JIQ). A demographic questionnaire was also used to collect information on age, sex, education level, work experience, and shift work.

The BPAQ, designed by Buss & Perry (1992), measured the aggression of nurses. It is a 29-item self-report instrument with four subscales of hostility (8 items), physical aggression (9 items), anger (7 items), and verbal aggression (5 items). It is scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (extremely uncharacteristic) to 5 (extremely characteristic). Two items are reverse-scored, and higher total scores indicate a higher level of aggressive behavior.

The reliability of its Persian version has been confirmed by Bahrami et al. (2012), and its Cronbach α has been reported to be 0.89. Additionally, the test, re-test reliability is 0.78 for the whole scale, ranging from 0.61 to 0.74 for the subscales (Karimi et al., 2013). The Cronbach α coefficient for the whole instrument was 0.78 in our research.

The SWBS is a tool for self-assessing perceived spiritual well-being, created by Paloutzian and Ellison in 1982. It has 20 items and is scored on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely agree) to 6 (completely disagree) for negatively worded items and from 6 (completely disagree) to 1 (completely agree) for positively worded items. This scale measures spiritual well-being in two senses: religious and existential, each with 10 items and a score of 10-60. The total score of the SWBS ranges from 20 to 120. A score of 20 to 40 indicates a low level, a score of 41 to 99 indicates a moderate level, and a score of 100 to 120 indicates a high level of spiritual well-being. The SWBS is a reliable and valid instrument, with Cronbach’s α coefficients ranging from 0.89 to 0.94 (Bufford, 1991). We used its Persian version to measure the spiritual well-being of nurses. Rezaei et al. (2009) confirmed the validity of the Persian version of SWBQ and reported its Cronbach α coefficient as 0.82. In our study, the Cronbach α coefficient was 0.82. We used the whole score of the scale.

The JIQ is a 10-item measure of job involvement developed by Kanungo in 1982, scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 5 (completely agree) to 1 (completely disagree). The total score ranges from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater job involvement. The internal consistency and test, re-test reliability coefficients of this scale are α=0.87 and r=0.85, respectively (Kanungo, 1982). We used the Persian version of this tool to measure the job involvement of nurses. Zabani Shadabad et al. (2017) used the Persian version of this questionnaire with 350 university employees and reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.89. In our study, Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.83.

Intervention

The experimental group underwent eight 90-minute sessions of compassion-based training, while the control group received no training. The intervention was conducted by a health psychology specialist, once a week for two months. Considering that this study coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic and preventive measures such as quarantine and social distancing were implemented, nurses could not be physically present in one location; therefore, virtual education was used. The education was presented using WhatsApp Messenger. The audio files of the sessions were also prepared and sent to the participants, along with their homework. At the beginning of each session, the educational materials covered in the previous session were reviewed, and homework was recapped. Nurses could discuss their questions with the health psychology expert or receive their homework training packages in the interval between the two sessions. The content of the intervention was adapted from Neff and Germer (2018) (Table 1).

Data analysis

Data analysis was done using multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) to investigate the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variables, and the paired t-test for within-group comparisons in the control and intervention groups at the pre-test and post-test phases, and the independent t-test for between-group comparisons at the pre-test and post-test phases. Frequency distribution, percentage, Mean±SD were also used. SPSS software, version 24 was used for the analysis. Before conducting MANCOVA, the assumptions were checked. According to the Shapiro-Wilk test results, the statistical distribution of the dependent variables was normal (P>0.05). The assumption of homogeneity of variances across various levels of the independent variables was accepted (P>0.05) using Levene’s test. Based on the F statistic value, the assumption of equality of regression coefficients in the groups was also accepted (P>0.05). Therefore, the assumptions of MANCOVA were established. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

No significant difference was detected in personal characteristics between the two groups (Table 2).

Within-group analyses using paired t-tests revealed that the post-test BPAQ score was significantly higher than the pre-test score in the intervention group (P=0.023). This difference was not significant in the control group (P=0.345). Similarly, the post-test SWBS score was significantly higher than the pre-test score in the intervention group (P=0.033), whereas no significant difference was observed in the control group (P=0.40). Additionally, the post-test JIQ score was significantly higher than the pre-test score in the intervention group (P=0.012), whereas this comparison was not significant in the control group (P=0.672) (Table 3).

Using an independent t-test, between-group comparisons revealed that the pre-test scores of BPAQ, SWBS, and JIQ were not statistically significant (P>0.05). Still, the difference in post-test scores was significant regarding BPAQ (P=0.025), SWBS (P=0.034), and JIQ (P=0.026) (Table 3).

The results of the between-group comparisons for the BPAQ score (Table 4) showed that, after adjusting for the pre-test score, the post-test score was significantly different between the two groups (F=11.62, P=0.002).

Eta-squared=0.33, indicating that 33% of the improvement in nurses’ anger management was attributed to self-compassion training. Since the effect of the control variable (pre-test) was significant (P<0.001), the adjusted mean value was obtained by removing its impact from the main intervention. The adjusted mean score of BPAQ in the intervention group (79.36) improved compared to the control group (71.47).

The results of between-group comparisons for the SWBS score (Table 4) showed that, after adjusting for the pre-test score, the post-test score was significantly different between the two groups (F=5.57, P=0.027). Eta-squared=0.19, which shows that a 19% improvement in nurses’ spiritual well-being was due to self-compassion training. The adjusted mean score of SWBS in the intervention group (69.85) improved compared to the control group (66.60).

The results of the between-group comparisons for the JIQ score (Table 4) showed that, after adjusting for the pre-test score, the post-test score was significantly different between the two groups (F=6.91, P=0.015). Eta-squared was equal to 0.23, indicating that self-compassion training accounted for a 23% improvement in nurses’ job involvement. The adjusted mean score of JIQ in the intervention group (90.3) improved compared to the control group (83.8).

Discussion

This research investigated the effectiveness of self-compassion training on anger management, spiritual well-being, and job involvement of nurses working in Rasht hospitals. The protocol proposed by Neff and Germer (2018) was used to design the compassion-based education intervention. The results showed that self-compassion training markedly decreased nurses’ anger. The eta-squared value showed that a 33% improvement in nurses’ anger management was due to self-compassion training. In many cases, the angry mood and angry reaction are due to the surrounding people; using self-compassion training and emphasizing kindness and non-judgment, nurses realized that judging the behavior of the people around them led to the creation of such a mood and using the solutions presented in the treatment sessions, these reactions could be overcome. Additionally, self-compassion training reduced the physical tendency to anger, and by practicing compassionate speech, actions, and visualization, the subjects, who were nurses, could control their angry physical tendencies. The results mentioned above are in line with those of Naismith (2016), who investigated self-compassion/forgiveness interventions for anger and aggression in couples’ behavior, and Moradi (2022), who studied the effect of compassion techniques on anger and aggressive behaviors in mothers with mentally disabled children. They showed that compassion-focused therapy reduced anger and aggressive behaviors. Basharpoor and Ahmadi (2016) investigated the association between the dimensions of self-compassion and anger control and the prevalence of suicidal thoughts in people addicted to heroin. They reported that the prevalence of suicidal thoughts had a significant negative association with the level of mindfulness. Also, the prevalence of suicidal thoughts had a meaningful and positive relationship with isolation, excessive assimilation, self-judgment, internal and external anger, and angry tendencies. Teaching self-compassion is effective in controlling anger, as tolerance of distress is a key dimension of the compassion model.

Additionally, resilience and learning to use anger control require patience and tolerance of distress. These observations are consistent with our findings. Miyagawa and Taniguchi (2020) investigated the association between self-compassion and the way individuals experience unpleasant past-related events. They found that individuals with higher self-compassion experienced less anger when recalling past frustrating situations. Additionally, Darvei et al. (2019) reported that increasing self-compassion levels among nurses has a significant impact on stress reduction and job burnout.

Teaching self-compassion could increase the spiritual well-being of nurses. The eta-squared value showed that a 19% improvement in nurses’ spiritual well-being was due to self-compassion training. People who experience a greater search for the meaning of life are at a higher level of spiritual well-being and always experience positive emotions (e.g. joy, vitality, will), are more satisfied with life in the process of searching for meaning, and have a greater ability to endure stressful situations (Hooker et al., 2019).

Similarly, purposeful and hopeful thinking, along with familiarity with the necessary paths to achieve one’s goals, will lead to a deeper search for life’s meaning and greater inner satisfaction. Therefore, choosing appropriate goals and trying to achieve them can be called goal-oriented or optimistic thinking. If a person experiences satisfaction with life and more happiness, and only occasionally experiences emotions such as sadness and anger, they have high spiritual well-being. On the contrary, if they are dissatisfied with their life, they experience little happiness and interest, and continuously feel negative emotions, such as anger and anxiety, indicating low spiritual well-being (Hooker et al., 2019).

Jafari (2015) and Fazeli Kebria et al. (2021) demonstrated that individuals with high spiritual well-being tend to be satisfied with their family life, engage in favorable social interactions, have numerous friends, and experience fewer negative emotions. Based on Snyder’s theory of hope, having a hopeful mindset, sufficient resources for goal-oriented thinking, and familiarity with the necessary paths to achieve goals make life meaningful. In other words, an increase in hope leads to an increase in meaning, and an increase in meaning also causes an increase in hope or goal-oriented thinking. Based on the findings of this hypothesis and studies by Kazemi et al. (2019) and Mohamadian and Rasouli (2019), an increase in meaning leads to an increase in happiness, positive emotions, and life satisfaction and a reduction in both or one of these two lead to the rise in anxiety and depression. Similar to our results, Hashemi (2018) reported a positive effect of group self-compassion training on employees experiencing burnout.

Self-compassion training could increase nurses’ job involvement. The eta-squared value showed that a 23% improvement in nurses’ job involvement was due to self-compassion training. These findings support those of Rushforth et al. (2023), Darvei et al. (2019), and Khedmati (2020). Self-compassion enables individuals to care for themselves, cultivate awareness, and adopt a non-judgmental attitude towards their failures and inadequacies, ultimately accepting that their experiences are part of the normal human experience. Self-compassion serves as a construct that combines three key components: self-kindness versus self-judgment, mindfulness versus extreme assimilation, and human commonality versus isolation. The combination of these three components enables individuals to develop a perceptive system, after which they come to understand their nature, and based on this, they can exhibit appropriate reactions in times of crisis. Self-compassion serves as a mechanism by which people can identify and adjust their behavioral patterns in response to their environment. Compassion training enables individuals to be more receptive to others and accept them without prejudicial and negative judgments. It also encourages people to be kinder and more sensitive to the needs of others (Neff, 2003). Increasing the capacity of individuals in self-awareness, empathic concerns, and emotional regulation through mindfulness provides a step toward enhancing the communication capacity of nurses.

The limitations of using a self-report questionnaire in this study were unavoidable. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic’s occurrence during the study limited sample selection and the method of implementing the intervention. Given that most of the participating nurses were female, it is suggested that the effect of gender differences on the results be investigated and compared with our findings.

Conclusion

Eight sessions of self-compassion training can improve anger management, spiritual well-being, and occupational engagement of nurses. Therefore, it is suggested that health policymakers include self-compassion training for all nurses as part of their professional development to strengthen the healthcare system and promote the mental health, well-being, and job satisfaction of nurses in the face of job stress.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUILAN.REC.1400.007). Hospital approval was also obtained. After explaining the study objectives and methods to the participants and noting that their information would remain confidential, written informed consent was obtained from each of them.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, study design, review, and editing: Azra Zebardast; Supervision: Iraj Shakerinia; Investigation, analysis, and writing the original draft: Nima Nateghian; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the cooperation of the participants.

References

Afshani, S. A. & Abou’ee, A., 2019. [The effectiveness of self-compassion training in students’ anger control (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Family and Research, 16(3), pp. 103-24. [Link]

Asgari Tarazoj, A., Ali Mohammadzadeh, K. & Hejazi, S., 2018. [Relationship between moral intelligence and anger among nurses in emergency units of hospitals affiliated to Kashan University of Medical Sciences (Persian)]. Journal of Health & Care, 19 (4), pp. 262-71. [Link]

Au, T. M., et al., 2017. Compassion-based therapy for trauma-related shame and posttraumatic stress: Initial evaluation using a multiple baseline design. Behavior Therapy, 48(2), pp. 207-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.012] [PMID]

Bahrami, M. A., et al., 2012. [Moral intelligence status of the faculty members and staff of the Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences of Yazd (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, 5(6), pp. 81-95. [Link]

Baillie, L., et al., 2009. Nurses’ views on dignity in care. Nursing Older People, 21(8), pp. 22-9. [DOI:10.7748/nop2009.10.21.8.22.c7280] [PMID]

Basharpoor, S., Daneshvar, S. & Noori, H., 2016. The relation of self-compassion and anger control dimensions with suicide ideation in university students. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors and Addiction, 5(4), pp. e26165. [DOI:10.5812/ijhrba.26165]

Basharpoor, S. & Ahmadi, S., 2020. [Modelling structural relations of craving based on sensitivity to reinforcement, distress tolerance and self-Compassion with the mediating role of self-efficacy for quitting (Persian)]. Research on Addiction, 13(54), pp. 245-64. [Link]

Bluth, K. & Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A., 2017. Response to a mindful self-compassion intervention in teens: A within-person association of mindfulness, self-compassion, and emotional well-being outcomes. Journal of Adolescence, 57, pp. 108-18. [DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.04.001] [PMID]

Bufford, R. K., et ak, 1991. Norms for the spiritual weil-being scale. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 19(1), pp. 56-70. [DOI:10.1177/009164719101900106]

Buss, A. H. & Perry, M., 1992. The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), pp. 452-9. [DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452] [PMID]

Cha, J. E., et al., 2023. What do (and don’t) we know about self-compassion? Trends and issues in theory. Mechanisms, and Outcomes. Mindfulness, 14, pp. 2657-69. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-023-02222-4]

Cohen, J., 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. [Link]

Darvehi, F. , et al., 2019. [The impact of mindful self-compassion on aspects of professional quality of life among nurses (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology Studies, 10(34), pp. 89-108. [DOI:10.22054/jcps.2019.33577.1895]

Duncan, S. M., et al., 2016. Nurses’ experience of violence in Alberta and British Columbia hospitals. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive, 32(4), pp. 57-78. [Link]

Esmaeilpour, M., Salsali, M. & Ahmadi, F., 2011. Workplace violence against Iranian nurses working in emergency departments. International Nursing Review, 58(1), pp. 130-7. [DOI:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00834.x] [PMID]

Farahani Nia, M., et al., 2006. [Nursing students’ spiritual well-being and their perspectives towards spirituality and spiritual care perspectives (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Nursing, 18 (44), pp. 7-14. [Link]

Grodin, J., et al., 2019. Compassion focused therapy for anger: A pilot study of a group intervention for veterans with PTSD. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 13, pp. 27-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.06.004]

Hashemi, S. A, 2018. [The effectiveness of self-compassion training on burnout and job satisfaction of teachers (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Models and Methods, 9(31), pp. 25-46. [Link]

Health and Safety Executive., 2020. Work-related stress, anxiety or depression statistics in Great Britain, 2020. Merseyside: Health and Safety Executive. [Link]

Hooker , S. A., et al, 2019. Engaging in personally meaningful activities is associated with meaning salience and psychological well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(6), pp. 821-31. [DOI:10.1080/17439760.2019.1651895]

Hyland, S., Watts, J. & Fry, M., 2016. Rates of workplace aggression in the emergency department and nurses’ perceptions of this challenging behaviour: A multimethod study. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal, 19(3), pp. 143-48. [DOI:10.1016/j.aenj.2016.05.002] [PMID]

Hosseinipoor, Z. & Fallah, M., 2019. [The effectiveness of compassion training on communication skills and controlling the anger of the disciplines of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences in Yazd (Paersian)]. Paper presented at: The first conference on psychology, counseling and behavioral science, Tehran, Iran, 13 June 2019. [Link]

Huang, L. S., Molenberghs, P. & Mussap, A. J., 2023. Cognitive distortions mediate relationships between early maladaptive schemas and aggression in women and men. Aggressive Behavior, 49(4), pp. 418–30. [DOI:10.1002/ab.22083] [PMID]

Jafari, E., 2015. [Spiritual predictors of mental health in nurses: The meaning in life, religious well-being and existential well-being (Persian)]. Nursing and Midwifery Journal, 13(8), pp. 676-84. [Link]

Kanungo, R., 1982. Measurement of job and work involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(3), pp. 341-9. [DOI:10.1037//0021-9010.67.3.341]

Karimi, H., et al., 2013. [Comparing the effectiveness of group anger management and communication skills training on aggression of marijuana addicted prisoners (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Behavioural Sciences, 11(2), pp. 129-38. [Link]

Kazemi, Z., et al., 2019. [Study on the effect of spiritual well- being on the self- esteem and happiness of student –teachers (teacher training university in Gorgan-1396) (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi, 7(12), pp. 115-28. [Link]

Fazeli Kebria, M., Yadollahpour, M. H. & Gholinia Ahangar, H., 2021. [Relationship between spiritual intelligence and general health with the mediating role of spiritual well-being among university students (Persian)]. Journal of Religion and Health, 9(1), pp. 37-45. [Link]

Khandan, V., Hosseinzade, S. & Akbarpoor, T., 2022. [Examining the importance of job involvement in organizations (Persian)]. Paper presented at: 8th International Conference on New Perspective in Management, Accounting and Entrepreneurship, Tehran, Iran, 21 December 2022. [Link]

Khedmati, N., 2020. [The role of self-compassion and psychological flexibility in predicting the burnout of nurses (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi, 9(1), pp. 73-80. [Link]

Khosravi, S., et al., 2022. [The relationship between spiritual intelligence and anger in nurses working in emergency Departments of Educational Medical centers affiliated to the Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, 2021 (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research, 16(6), pp. 55-63. [Link]

Krieger, T., et al., 2019. An internetbased compassion-focused intervention for increased self-criticism: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 50(2), pp. 430-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2018.08.003] [PMID]

Grummitt L., et al., 2023. Self-compassion and avoidant coping as mediators of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mental health and alcohol use in young adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 106534. Advance online publication. [DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106534] [PMID]

Manshadi, M., 2019. The relationship between job involvement with organizational learning and organizational lnnovation among public school principals of meybod city. Journal of School Administration, 6(2), pp. 188-210. [Link]

Miyagawa, Y. & Taniguchi, J., 2020. Self-compassion and time perception of past negative events. Mindfulness, 11(2), pp. 746-55. [Link]

Mirzaee, R., Raesi, Z. & Kazemi, H., 2014. [The effectiveness of anger management and problem solving training on reduction of depression in prisoners (Persian)]. Sadra Medical Sciences Journal, 2(1) pp. 55-63. [Link]

Mirzaee, S., et al., 2022. [Effect of spiritual self-care education on the resilience of nurses working in the intensive care units dedicated to covid-19 patients in Iran (Persian)]. Complementary Medicine Journal, 12(2), pp. 188-201. [DOI:10.32598/CMJA.12.2.1166.1]

Mohamadian, R. & Rasoli, N., 2019. [Investigating the effect of spiritual well-being on the lifestyle of veterans with the role of happiness (case study: veterans of Rashtkhwar city) (Persian)]. Paper presented at: The 5th International Conference on Advanced Research Achievements in Social Sciences, Psychology and Psychology, Tehran, Iran, 21 September 2019. [Link]

Moradi, N., 2022. [The effectiveness of compassion therapy on resilience, emotional self-control and anger in mothers with mentally retarded children (Persian)]. Journal of New Developments In Psychology, Educational Sciences and Education, 5(52), pp. 61-75. [Link]

Naismith, I., 2016. “Barriers to compassionate imagery generation in personality disorder: Intra- and inter-personal factors [PhD dissertation]. London: UCL (University College London). [Link]

Neff, K. D., 2003. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), pp. 223-50. [DOI:10.1080/15298860309027]

Neff, K. & Germer, C., 2018. The mindful self-compassion workbook: a proven way to accept yourself, Build Inner Strenght, and Thrive. New York: Giuilford Press. [Link]

Novaco, R., 2020. Anger. In: V. Zeigler-Hill &T. K. Shackelford (Eds), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Cham; Springer. [Link]

Patil, M. R. & Mulimani, C. F., 2020. Improving Police Efficiency. Our Heritage, 68(1), pp. 813- 9. [Link]

Quinn, C. A., Rollock, D. & Vrana, S. R., 2014. A test of Spielberger’s state-trait theory of anger with adolescents: Five hypotheses. Emotion, 14(1), pp. 74-84. [DOI:10.1037/a0034031] [PMID]

Rabinowitz, S. & Hall, D. T., 1977. Organizational research on job involvemen. Psychological Bulletin, 84(2), pp. 265. [DOI:10.1037//0033-2909.84.2.265]

Rahmani, S., et al., 2020. [The effectiveness of self-compassion therapy on cognitive emotion regulation strategies and anxiety sensitivity in female nurses (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing (IJPN) Original Article, 8(4), pp. 99-110. [Link]

Rezaei, M., Seyed Fatemi, N. & Hosseini, F., 2009. [Spiritual well-being in cancer patients who undergo chemotherapy (Persian)]. Journal of Hayat, 14 (4 and 3), pp. 33-9. [Link]

Ross, L., et al., 2014. Student nurses perceptions of spirituality and competence in delivering spiritual care: A European pilot study. Nurse Education Today, 34(5), pp. 697-702. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2013.09.014] [PMID]