Tue, Jul 1, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 10, Issue 4 (Autumn 2024)

JCCNC 2024, 10(4): 287-296 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Eftekhari Moghaddam N, Shahbazi M, Moghaddam K K. Marital Commitment Mediates the Effects of Forgiveness and Alexithymia on Marriage Quality in Nursing Students. JCCNC 2024; 10 (4) :287-296

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-600-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-600-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, Masjed Soleiman Branch, Islamic Azad University, Masjed Soleiman, Iran. ,masoudshahbazi166@gmail.com

3- Department of Psychology, Dezful Branch, Islamic Azad University, Dezful, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, Masjed Soleiman Branch, Islamic Azad University, Masjed Soleiman, Iran. ,

3- Department of Psychology, Dezful Branch, Islamic Azad University, Dezful, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 751 kb]

(440 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1336 Views)

Full-Text: (110 Views)

Introduction

Nurses play a fundamental and vital role in the health of society (Wilandika et al., 2023). They interact with various patients in the hospital setting and constantly experience intense psychological pressure and anxiety. For this reason, nursing is recognized as one of the most stressful professions (Mazhari et al., 2022). Professionals in this field, who are responsible for the continuous care of patients, are at the highest risk of occupational injuries (Jeffreys, 2022). Due to their workplace characteristics and constant communication with patients, people in this profession are prone to numerous occupational stresses and health problems that may jeopardize their quality of life (QoL) (Orszulak et al., 2022). One of the features of QoL is marital quality (Gharibi et al., 2015). In general, the marriage relationship is considered one of the strongest human relationships, and its quality has various consequences for spouses, children, other family members, and ultimately society (Siadat et al., 2023). The family fulfills a vital role by providing for our essential needs across various physical, decision-making, and emotional domains. To effectively nurture a family environment, it is crucial to understand our biological, psychological, and emotional needs and how to fulfill them. An individual’s satisfaction with marital life means their satisfaction with the family, and satisfaction with the family means satisfaction with life, which will consequently facilitate society’s growth, development, and material and spiritual progress (Abbaszadeh et al., 2024).

Empirical evidence has established that marital quality is associated with various factors, among which interpersonal forgiveness stands out. Interpersonal forgiveness is a positive intrapersonal and social change in response to an interpersonal transgression (Ouyang et al., 2019). This definition encompasses changes that may involve either a decrease in negative affect or a reduction of negative emotions coupled with an increase in positive emotions. In either case, this change represents a positive social change to foster more positive social interactions (Azimian et al., 2017). In line with this, Kaveh Farsani (2021) demonstrated that the variable of apology directly and indirectly affects the quality of marital relationships through the mediating role of emotional forgiveness and marital empathy.

On the other hand, research has shown that alexithymia in individuals affects their marital quality (Zakeri & Rezaei, 2022). Alexithymia is a psychological problem that hinders individuals’ well-being. When individuals are emotionally competent, they can enhance their mental health when facing life challenges (Shahmardi et al., 2022; Falahati & Mohammadi, 2020). Individuals who are deficient in identifying and appropriately applying their emotions may lack the ability to utilize their emotional world, leading to a decrease in positive emotions such as happiness and an increase in anxiety (Alexander et al., 2021). In this regard, Wells et al. (2016) established a significant relationship between alexithymia and its constituents (difficulty identifying emotions, difficulty describing emotions, and objective thinking) and perceived marital relationship quality.

Marital commitment significantly influences interpersonal forgiveness and emotional expression in married individuals and enhances marital quality (Nemati et al., 2022). A quality marriage includes key elements such as commitment, attraction, and understanding, among which marital commitment is the strongest and most stable predictor of marital quality and stability (Hou et al., 2019). Marital commitment entails a long-term perspective on marriage, willingness to sacrifice the relationship, preserving, strengthening, maintaining unity, and living with a spouse even when marriage does not bring rewards (Allen et al., 2022). In other words, marital commitment is a protective factor against marital breakdown and the most stable predictor of marital quality and stability (Aman et al., 2021). In line with this, Lin et al. (2022) found a significant association between marital commitment and quality in married men and women.

In general, problems arising in married individuals decline interpersonal and marital relationships, which in turn contributes to divorce among couples, which is the most acute and serious communication problem in families. Problems related to marital relations in nursing students who will form a considerable part of the treatment team soon can ultimately negatively affect patient care. Therefore, according to the above points and the importance of addressing the factors affecting the quality of marriage in this group of therapeutic strata, the present study investigated the mediating role of marital commitment in the relationship between interpersonal forgiveness, alexithymia, and marital quality in nursing students in Ahvaz City, Iran.

The most important hypotheses of this study are as follows:

1. There is a positive association between interpersonal forgiveness, marital quality, and marital commitment in nursing students.

2. There is a positive association between marital commitment and marital quality in nursing students.

3. There is a negative association between alexithymia and marital commitment in nursing students.

4. Forgiveness and alexithymia significantly indirectly affect marital quality through the mediating role of marital commitment.

Materials and Methods

The present study employed a descriptive correlational research design to examine the relationships between the variables within the structural equation modeling (SEM) framework. The target population comprised all nursing students at Ahvaz Islamic Azad University during the 2022-2023 academic year. A convenience sampling method was used to select the sample, and the research questionnaires were distributed among them. The inclusion criteria for the study were willingness to participate in the research, complete response to all questions, and being married for at least 1 year. The exclusion criterion was an incomplete response to the questions. In SEM, the sample size is calculated based on the number of direct paths, exogenous variables, and error variances. According to Kline’s (1998) suggestion, a sample size of 200 is sufficient, but considering the possibility of sample attrition, a sample size of 220 was considered. Ultimately, 204 samples thoroughly responded to the questionnaires and were included in the study.

Study instruments

Revised dyadic adjustment scale (RDAS)

The RDAS served as a brief measure of marital quality in this study. Developed by Busby et al. (1995), the RDAS features 14 items categorized into three subscales: consensus (items 1-6), satisfaction (items 7-10), and cohesion (items 11-14). All items utilize a 6-point Likert scale (0-5) except item 11, which employs a 5-point scale (0-4). Higher total scores (0-69) indicate greater marital quality. The Persian version of the RDAS has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, with a content validity index of 0.96 and a content validity ratio of 0.91, as Maroufizadeh et al. (2020) reported. Additionally, they documented a Cronbach α of 0.85 for the scale, indicating good internal consistency. In the present study, the scale’s internal consistency was estimated using the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.83.

Interpersonal forgiveness measurement questionnaire (IFMQ)

The IFMQ is a 25-item questionnaire developed by Ehteshamzadeh et al. (2011) to assess interpersonal forgiveness. It consists of three factors. Reconnection and revenge control (12 items) measures the individual’s willingness to reestablish a positive relationship with the transgressor and refrain from seeking revenge. Resentment control (6 items) assesses the individual’s ability to manage and reduce feelings of anger and resentment towards the transgressor. Finally, realistic understanding (7 items) measures the individual’s ability to understand the situation and the transgressor’s perspective from a realistic and non-judgmental standpoint. The IFMQ utilizes a 4-point Likert scale for scoring, with responses ranging from “strongly disagree”=1 to “strongly agree”=4. The total score for the entire scale ranges from 25 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of forgiveness. Items 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 25 are reverse-scored. The reliability of the Persian version of IFMQ was established by Ehteshamzadeh et al. (2011), who reported a Cronbach α of 0.80. In the present study, the internal consistency of the IFMQ was estimated using the Cronbach α coefficient, which was 0.86 for the total scale.

Toronto alexithymia scale (TAS)

The TAS is a 20-item self-report scale developed by Bagby et al. (2003) to assess alexithymia. It consists of three subscales. Difficulty identifying feelings subscale measures the individual’s difficulty recognizing and labeling emotions. Difficulty describing feelings subscale assesses the individual’s difficulty communicating emotions to others. Finally, the external-oriented thinking subscale measures individuals’ tendency to focus on external factors and events rather than their internal emotional states. The scale utilizes a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree) for item scoring. Scores ≤51 indicate low alexithymia, while scores ≥61 indicate high. Items 4, 10, 18, and 19 are reverse-scored. The total score for the scale is calculated by summing the scores of all items. The minimum and maximum TAS scores are 20 and 100, respectively. Internal consistency of the TAS was established by Bagby et al. (2003), who reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.81. Besharat et al. (2008) reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.75 for the Persian version of the scale, indicating acceptable internal consistency. In the present study, the internal consistency of the TAS was estimated using the Cronbach α coefficient, which was 0.82.

Dimensions of commitment inventory (DCI)

The DCI is a 44-item questionnaire developed by Adams & Jones (1997) to measure three dimensions of marital commitment. The personal commitment dimension assesses the individual’s commitment to their spouse based on their perceived attractiveness and personal qualities. The moral commitment dimension measures the individual’s commitment to marriage based on their belief in the sanctity and importance of the marital relationship. Finally, the structural commitment dimension assesses the individual’s commitment to their spouse and marriage based on feelings of obligation, pressure to continue the marriage, and fear of the consequences of divorce. The DCI is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1: Strongly disagree to 5: Strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of commitment. The total score for the questionnaire is calculated by summing the scores of all items. The highest and lowest possible scores are 220 and 44, respectively. A score closer to 220 indicates high commitment, while a score closer to 44 indicates low commitment. Adams & Jones (1997) further reported the reliability of the DCI subscales, with Cronbach α coefficients ranging from 0.86 to 0.91. Mortezaei & Rezazade (2021) established the reliability of the Persian version of the inventory with a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.85. In the present study, the internal consistency of the DCI was estimated using the Cronbach α coefficient, which was 0.84.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using a combination of descriptive and inferential techniques. Descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD, were employed to characterize the distribution of the research variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient was utilized to assess the relationships between the variables. SEM was also implemented to examine the hypothesized relationships within a comprehensive framework. Analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 27 for initial data exploration and AMOS software, version 24.0 for SEM analysis.

Results

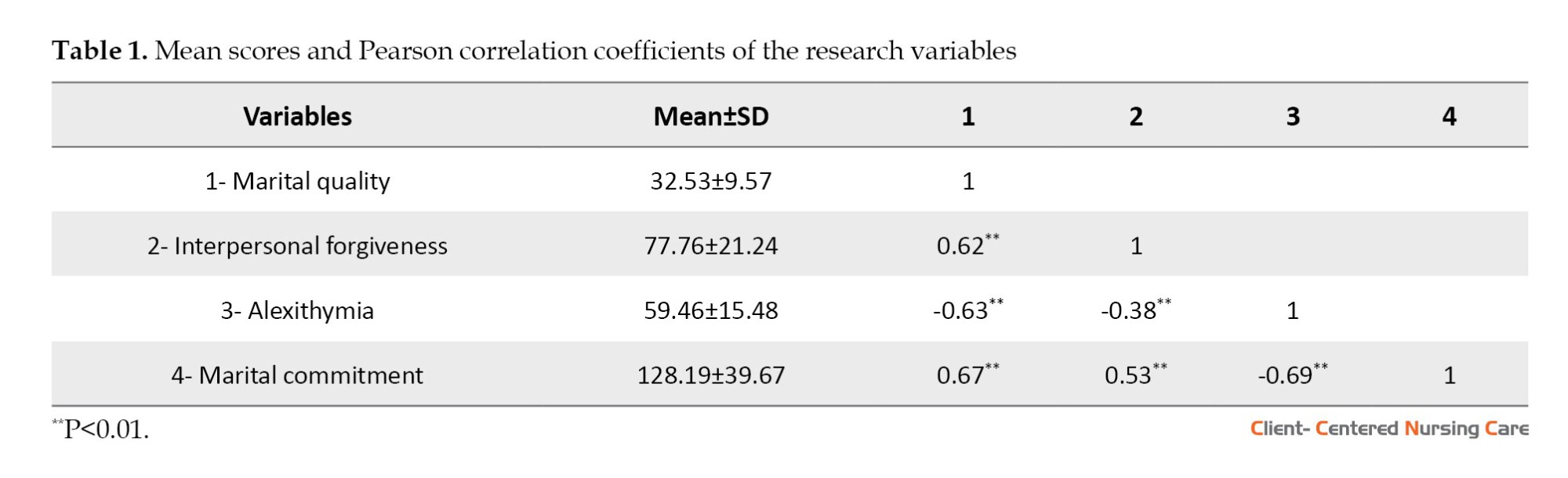

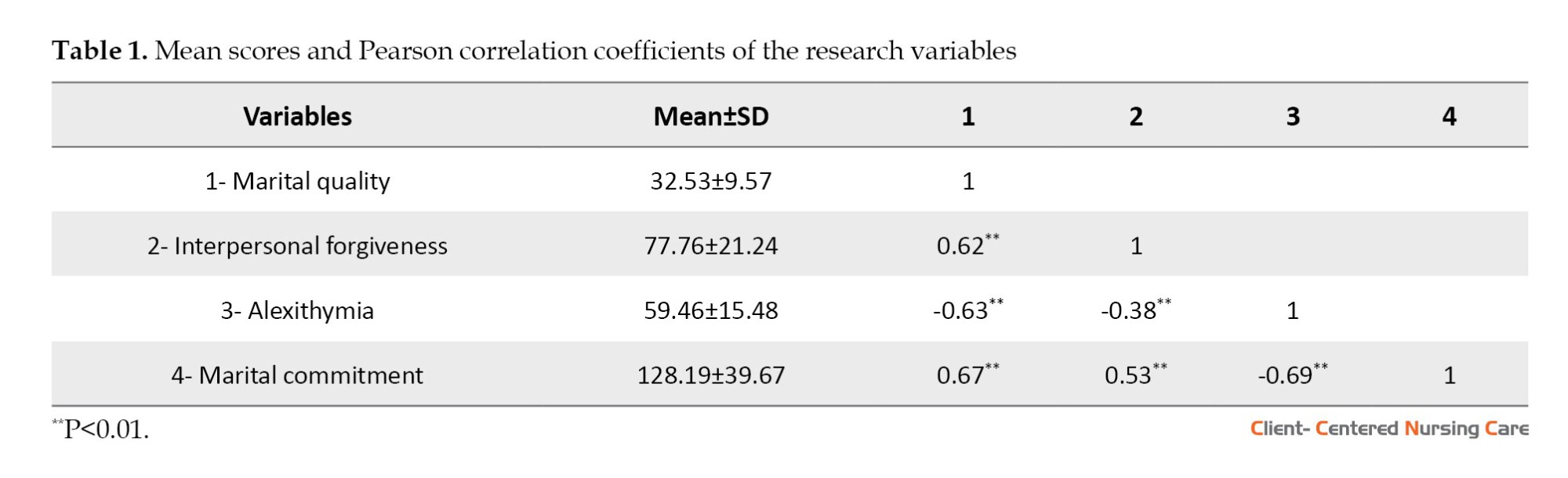

The subjects comprised 204 nursing students with a mean age of 26.87±6.40 years. Of the participants, 148(72.55%) were female and 56(27.45%) were male. The Mean±SD of the study variables are presented in Table 1.

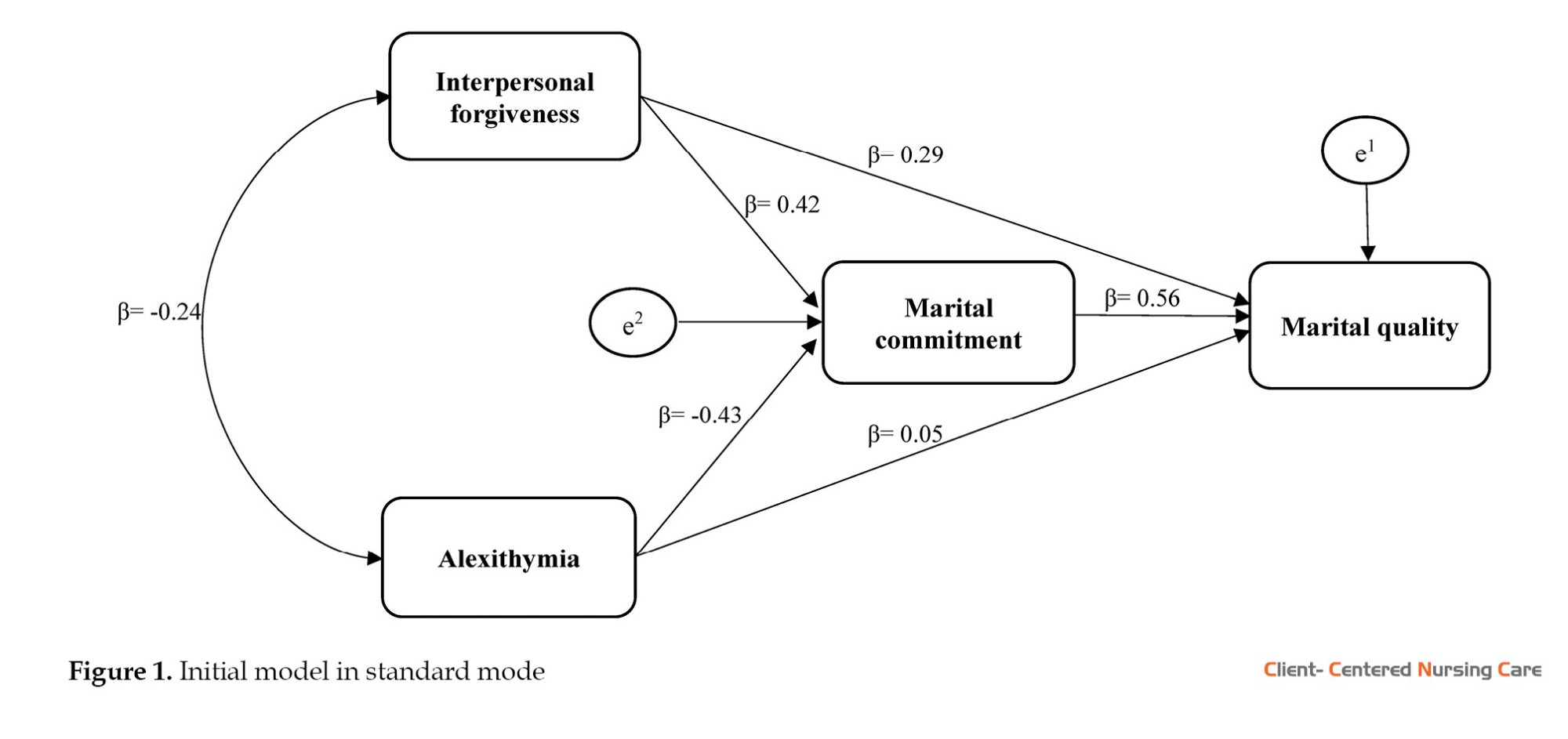

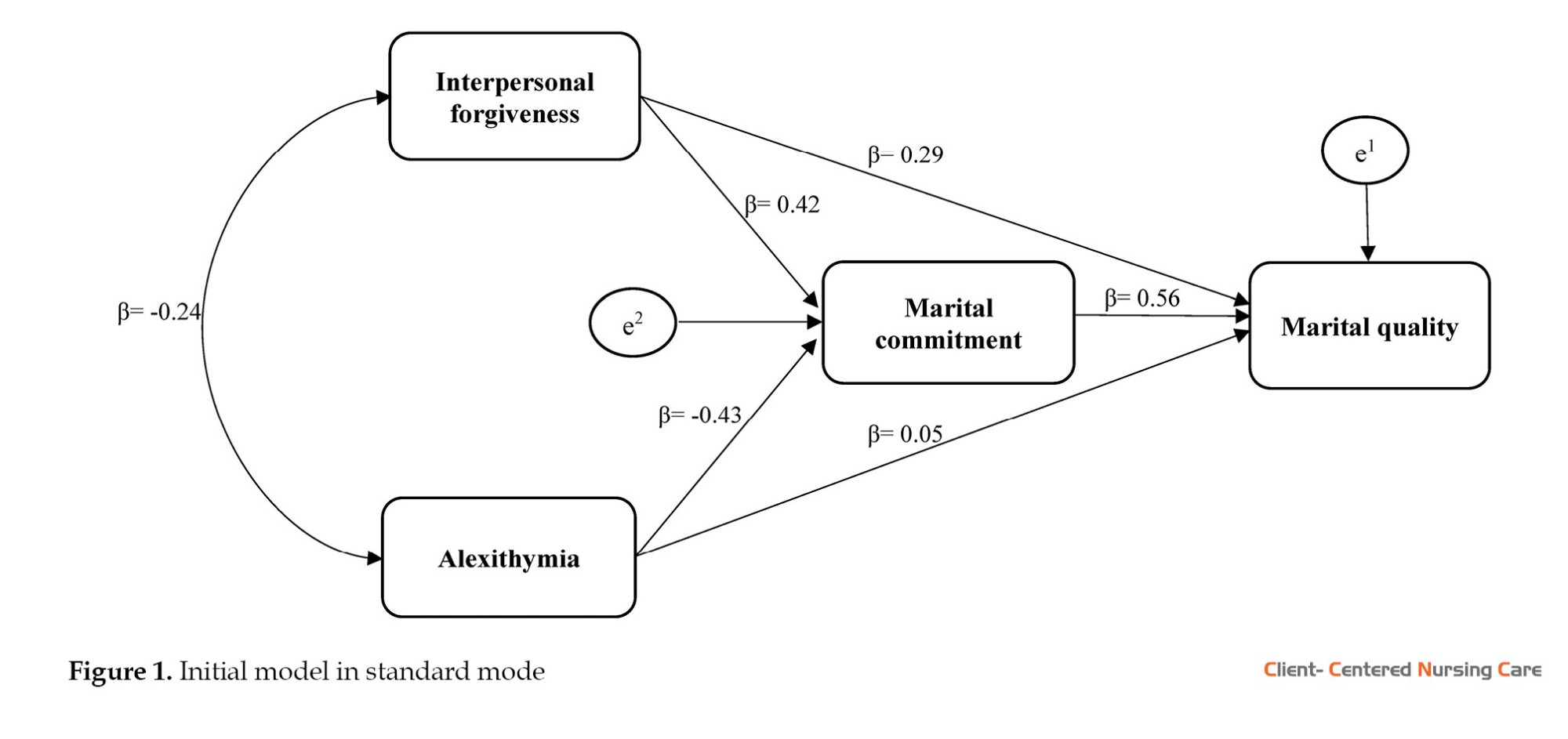

Table 1 also shows the Pearson correlation coefficients between the study variables. Statistically significant correlations were found between marital quality and forgiveness (r=0.62, P<0.01), marital quality and commitment (r=0.67, P<0.01), and alexithymia and forgiveness (r=-0.38, P<0.01). These correlations indicate that higher levels of forgiveness and commitment are associated with better marital quality, while higher levels of alexithymia are associated with lower marital quality. An initial preliminary model was developed to explain marital quality based on interpersonal forgiveness, alexithymia, and marital commitment, as shown in Figure 1.

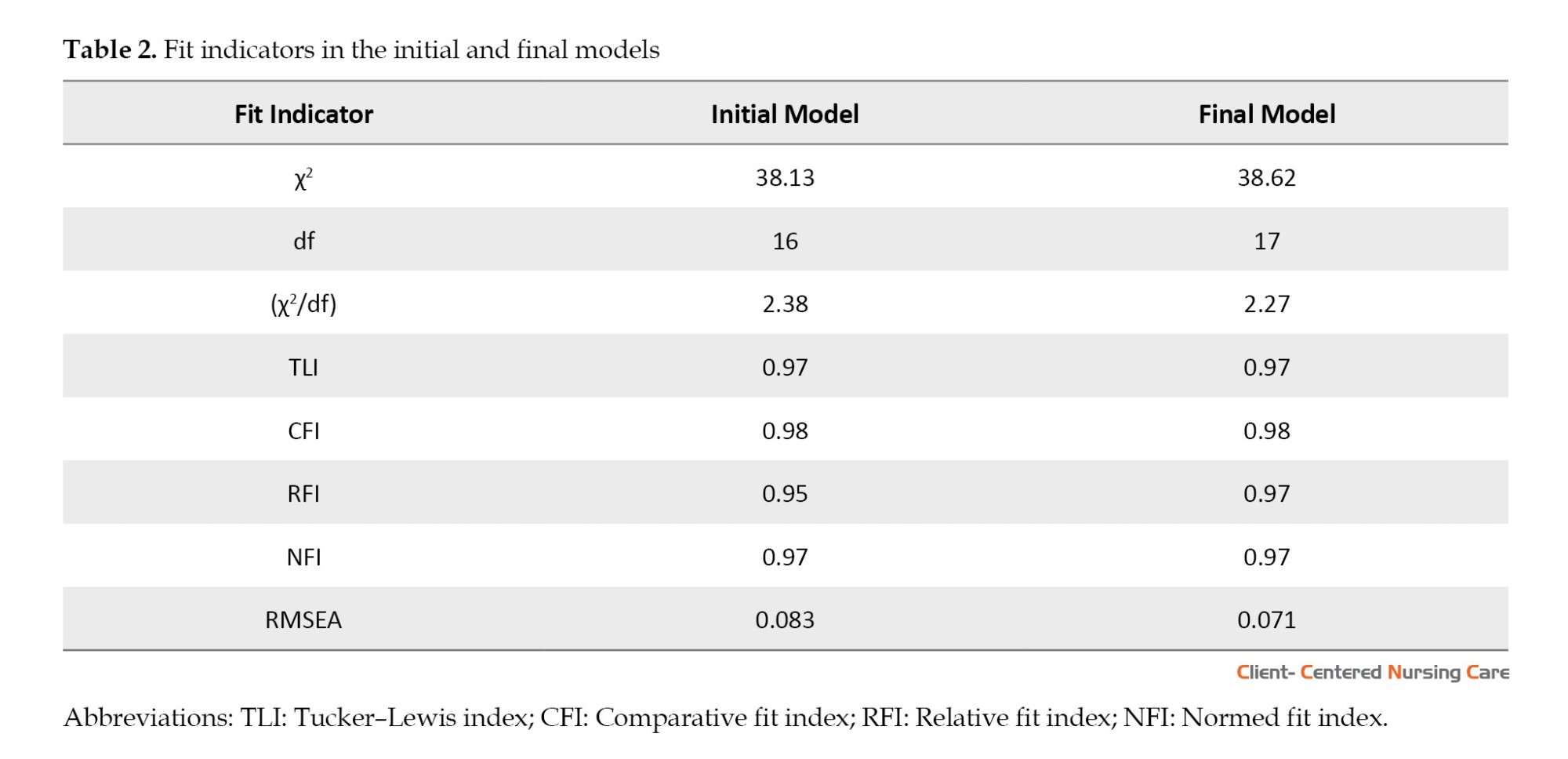

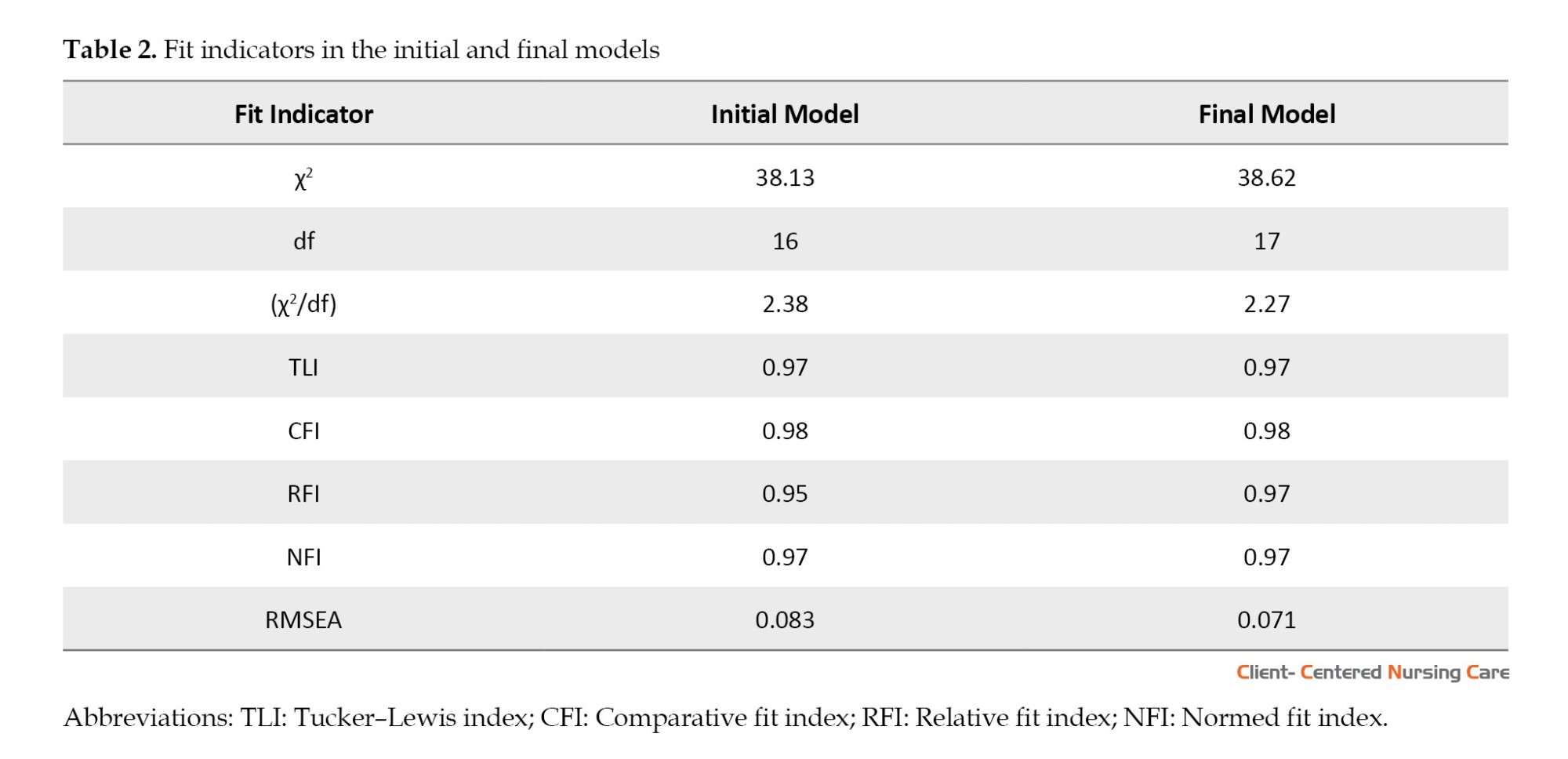

Based on the data in Table 2, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) index was 0.083, indicating that the initial model needed to be modified.

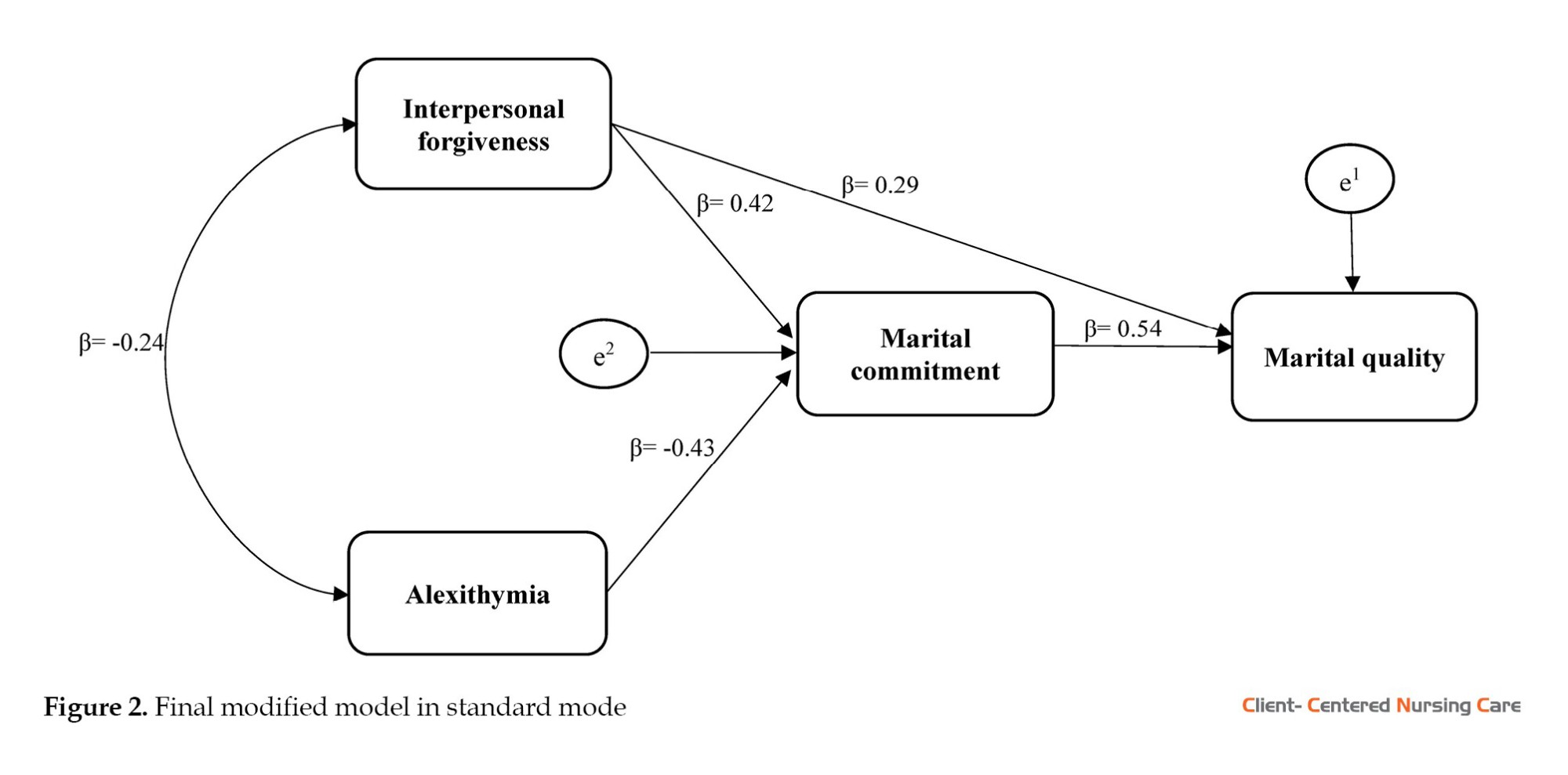

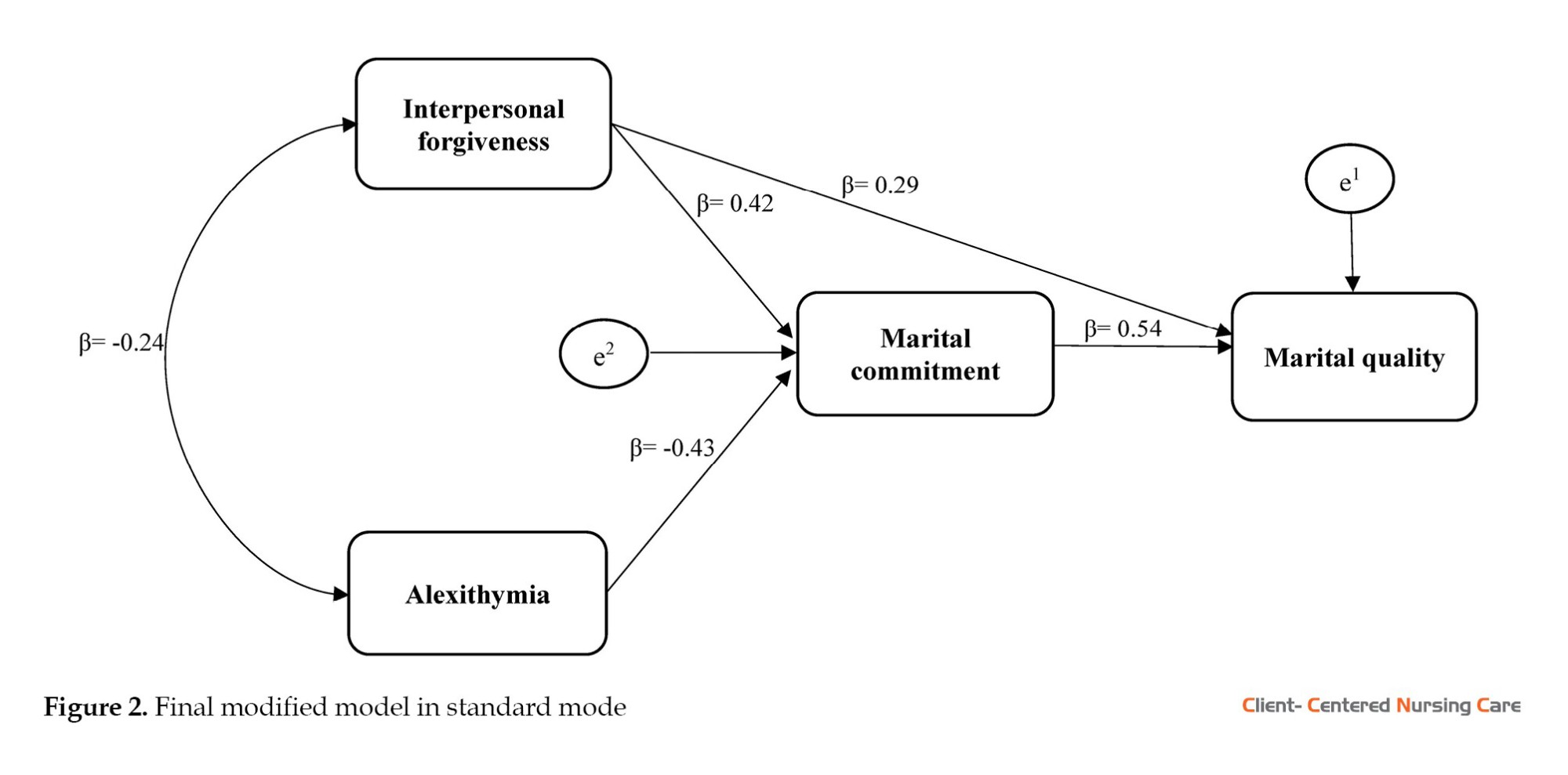

After removing one of the paths (alexithymia to marital quality) in the final model, the RMSEA index was 0.071, indicating a good fit for the model. The final modified model is presented in Figure 2.

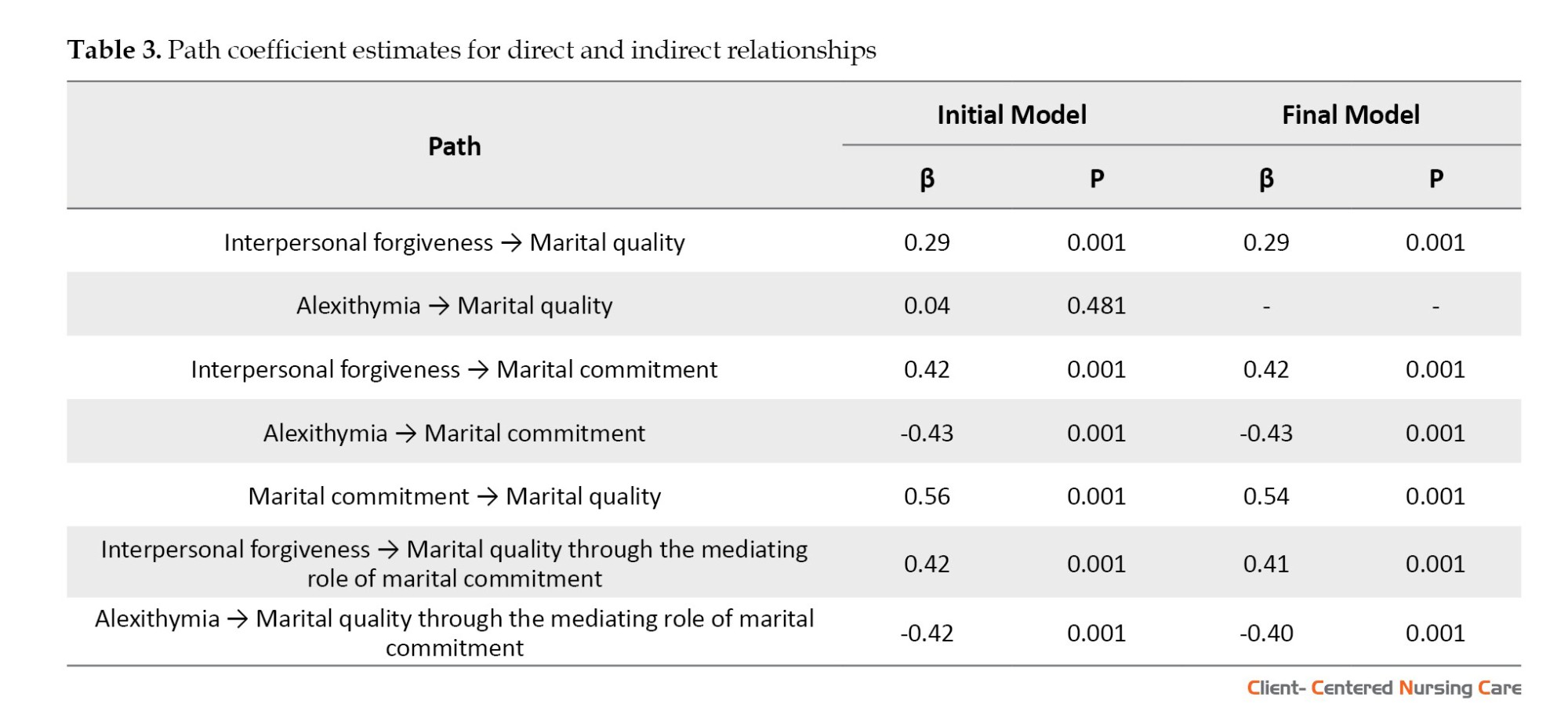

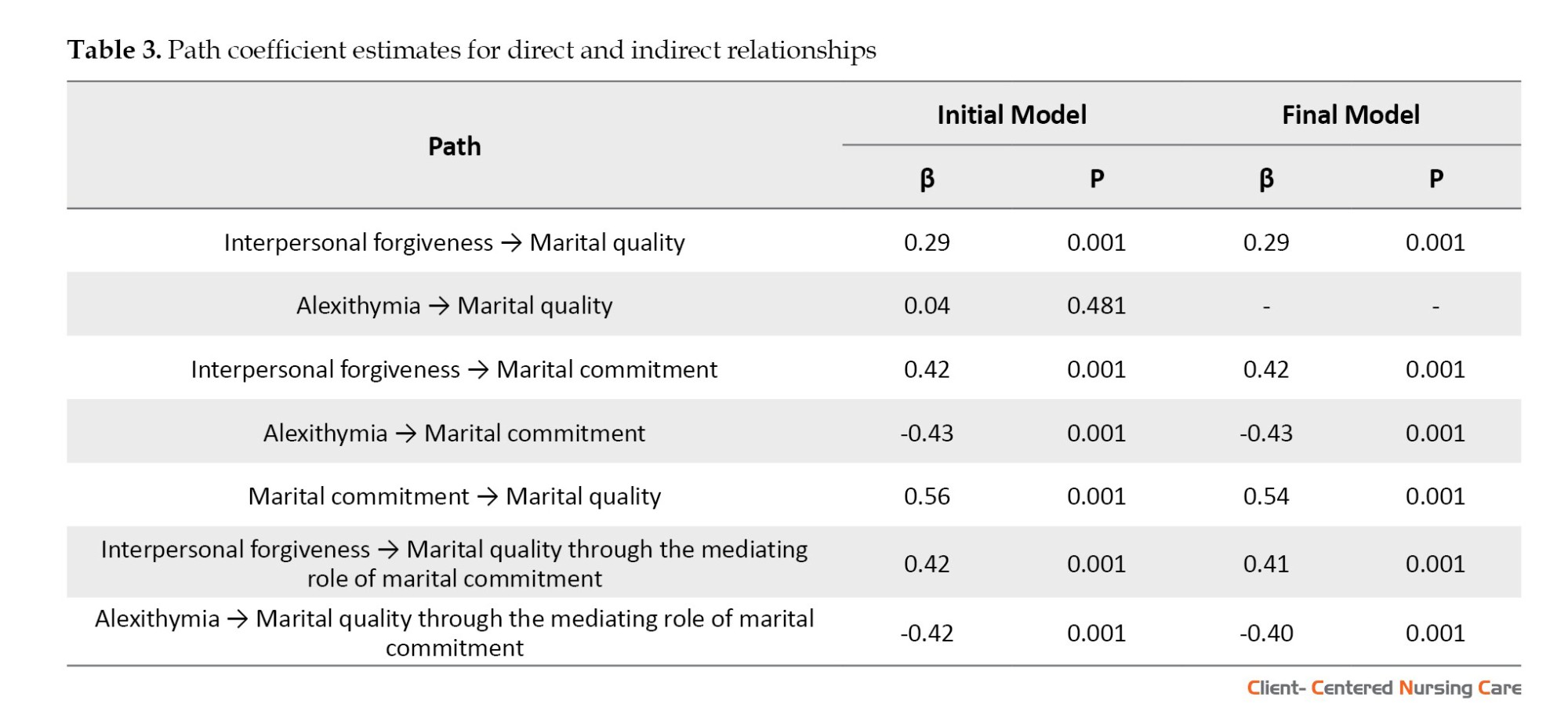

Table 3 presents the findings related to the path coefficient estimates for both direct and indirect relationships. The study yielded significant results regarding the relationships between forgiveness, emotional expression (measured by alexithymia), marital commitment, and marital quality in nursing students. The findings revealed that interpersonal forgiveness strongly correlated with marital quality and commitment (P<0.001), supporting the first hypothesis. Similarly, marital commitment demonstrated a positive and significant correlation with marital quality (P<0.001), confirming the second hypothesis. Alexithymia exhibited a negative and significant association with marital commitment (P<0.001), supporting the third hypothesis. However, it did not directly impact marital quality. Interestingly, both forgiveness and alexithymia demonstrated significant indirect effects on marital quality through the mediating role of marital commitment (P<0.001). This finding aligns with the fourth hypothesis.

Discussion

The present study investigated the mediating role of marital commitment in the relationship between interpersonal forgiveness, alexithymia, and marital quality in nursing students. The first finding indicates a significant relationship between interpersonal forgiveness and marital quality. This finding is consistent with the study’s results by Fatehi et al. (2021).

One possible explanation for this finding is that admitting mistakes and apologizing in close relationships lead to interpersonal forgiveness, reducing distress, anger, and revenge. Interpersonal forgiveness can help reduce destructive behaviors that stem from injustice, and increasing empathy and compassion can enhance interpersonal forgiveness in the relationship. Spouses who can engage in the relationship repair cycle are more effective in preventing the effects of damage to the relationship and maintaining or increasing marital quality in the face of events (Brandão et al., 2020). Interpersonal forgiveness is defined as a positive interpersonal and social change in response to a transgression that occurs in the interpersonal realm. According to this definition, interpersonal forgiveness encompasses changes that can be accompanied by a decrease in negative emotions or a decrease in negative emotions along with an increase in positive emotions. Given the role of interpersonal forgiveness in reducing negative and increasing positive emotions, it can be seen that interpersonal forgiveness is associated with high marital quality (Fatehi et al., 2021). When an individual is capable of interpersonal forgiveness, the relationship between the violation, marital quality, and marital satisfaction is weakened. Individuals capable of forgiving their spouse interpersonally believe in the sanctity of their marital relationship, and this ability to forgive their spouse interpersonally leads to greater strength in marital quality and increased marital quality satisfaction.

The results show that the relationship between alexithymia and marital quality in nursing students is not significant. This finding is inconsistent with the results of the study by Hashemi (2021). It can be argued that in the mentioned study, the relationship between alexithymia and marital quality was examined using correlation and regression tests, and this relationship was found to be significant. In contrast, the hypotheses were tested using SEM in the present study. The relationship between alexithymia and marital quality was also significant based on the Pearson test. Still, in the model, due to the presence of a mediator variable, the total variance and effect of alexithymia on marital quality were explained through the mediator variables or the indirect relationship. In other words, in this model, alexithymia still affects marital quality, but indirectly. One possible explanation for this finding is that individuals who can recognize their emotions and effectively express their emotional states are better able to cope with life’s problems and are more successful in adapting to the environment and others.

In contrast, individuals with alexithymia experience confusion and helplessness in the cognitive processing, perception, and evaluation of emotions due to their inability to identify and regulate emotions. This inability can disrupt their emotional and cognitive organization and make successful adaptation difficult (Zakeri & Rezaei, 2022). As a result, the couple’s relationships become conflicted, boring, and lacking in intimacy, reducing marital quality. This is because romantic and satisfying relationships require the ability to identify and express emotions to one’s partner. Therefore, alexithymia in couples predicts marital conflicts (Hashemi, 2021).

The results also show that the relationship between marital commitment and quality is statistically significant. This finding is consistent with the study’s results by Moghimi et al. (2022). One possible explanation for this finding is that a strong commitment and dedication between partners can improve their marital quality. When both individuals respond positively to the challenges of their lives together with confidence and determination, a sense of security and strength in their relationship is strengthened. The time and effort required to solve the problems and concerns of the relationship play a significant role in increasing the quality of marital life (Aman et al., 2021). Additionally, accepting the relationship’s shortcomings and challenges can contribute to individual and relationship growth. Moreover, maintaining strong and sincere emotional feelings between both individuals in the marital relationship can be the key to happiness and well-being in this sensitive relationship.

The results show that the relationship between interpersonal forgiveness and marital quality is significant, with marital commitment as a mediator. Additionally, the results indicate that the relationship between alexithymia and marital quality is significant, with marital commitment as a mediator. No similar study was found regarding these findings, and this research is the first to examine the variables included in this hypothesis. Orathinkal and Vansteenwegen (2006) found a positive association & forgiveness and general life adjustment, suggesting that individuals with higher levels of forgiveness may experience better overall adjustment in various life domains. Moreover, Braithwaite et al. (2011) reported that forgiveness could lead to happier relationships through increased effort and less fighting. There was a significant and direct association between interpersonal forgiveness and marital quality. The results also show that interpersonal forgiveness increases marital quality in nursing students by increasing marital commitment. Interpersonal forgiveness is a crucial factor in enhancing marital quality. This forgiveness can contribute to marital commitment in married life and consequently improve the family’s overall functioning and marital relationship (Orathinkal and Vansteenwegen, 2006).

The results show that interpersonal forgiveness positively correlates to marital commitment in this group. Building upon Tsang et al.’s (2006) work, our findings add to the multifaceted influence of forgiveness on marital quality. While they identified revenge and benevolence as dimensions of forgiveness that promote later closeness and commitment, our study suggests a more complex interplay. Here, forgiveness as a whole, encompassing its various dimensions, positively influences these aspects of marital quality. In more precise terms, married individuals with higher levels of interpersonal forgiveness, as a mastery and complete and acceptable understanding of their spouse’s needs, show higher marital commitment to their spouse. The direct relationships show that alexithymia lacks a significant relationship with marital quality. The relationship between alexithymia, marital quality, and marital commitment in nursing students is an important issue, indicating the connection between an individual’s emotional and mental state and their marital life functions. Unpleasantness in couples’ relationships may be due to the inability to establish healthy and proper communication with the spouse, the inability to solve family problems, lack of commitment to the marital relationship, incorrect thinking about the challenges of married life, and so on (Lin et al., 2022; Stanley et al., 2010). Additionally, deficiencies in marital interactions can lead to behavioral disorders (negative interactions, emotional dryness, hidden resentment) (Irani et al., 2022). Therefore, marital commitment adequately plays the role of a mediating variable in the relationship between interpersonal forgiveness and alexithymia with marital quality.

Conclusion

This study examined the interplay between interpersonal forgiveness, alexithymia, marital commitment, and marital quality in nursing students. The findings supported our hypotheses, revealing positive associations between forgiveness and marital quality and commitment. Additionally, marital commitment emerged as a significant positive predictor of marital quality, underlining its critical role in marital satisfaction. Interestingly, while alexithymia exhibited a negative correlation with marital commitment, it did not directly impact marital quality. However, the indirect effects analysis revealed a significant mediating role for marital commitment. Specifically, alexithymia indirectly reduces marital quality by decreasing marital commitment. These findings suggest that marital commitment is a crucial mediator in linking forgiveness and alexithymia to marital quality. In simpler terms, nursing students with higher levels of forgiveness and lower levels of alexithymia tend to report better marital quality, primarily because these factors contribute to stronger marital commitment. This study paves the way for further investigations into the complex dynamics of marital relationships. Future studies could explore the potential mechanisms underlying the link between forgiveness and marital commitment. For instance, research could examine how forgiveness fosters positive communication or emotional responsiveness within the relationship, ultimately leading to stronger commitment. Additionally, investigating interventions to improve emotional expression skills and their potential impact on marital quality and commitment would be a valuable contribution to the field.

This study’s limitations include using self-report instruments, which may be susceptible to social desirability bias in the participants’ responses. Additionally, the sample restriction to nursing students in Ahvaz necessitates caution in generalizing the results to other married individuals in different cities.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1402.078). After a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, and potential risks and benefits, all subjects provided written informed consent. Additionally, permission to recruit the samples was obtained from the relevant faculty authorities at the university.

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Nasrin Eftekhari Moghaddam, approved by the Department of Psychology, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design and project administration: Nasrin Eftekhari Moghaddam, and Masoud Shahbazi; Data acquisition: Nasrin Eftekhari Moghaddam; Data analysis, interpretation and writing the original draft: Kobra Kazemian Moghaddam and Masoud Shahbazi; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Nurses play a fundamental and vital role in the health of society (Wilandika et al., 2023). They interact with various patients in the hospital setting and constantly experience intense psychological pressure and anxiety. For this reason, nursing is recognized as one of the most stressful professions (Mazhari et al., 2022). Professionals in this field, who are responsible for the continuous care of patients, are at the highest risk of occupational injuries (Jeffreys, 2022). Due to their workplace characteristics and constant communication with patients, people in this profession are prone to numerous occupational stresses and health problems that may jeopardize their quality of life (QoL) (Orszulak et al., 2022). One of the features of QoL is marital quality (Gharibi et al., 2015). In general, the marriage relationship is considered one of the strongest human relationships, and its quality has various consequences for spouses, children, other family members, and ultimately society (Siadat et al., 2023). The family fulfills a vital role by providing for our essential needs across various physical, decision-making, and emotional domains. To effectively nurture a family environment, it is crucial to understand our biological, psychological, and emotional needs and how to fulfill them. An individual’s satisfaction with marital life means their satisfaction with the family, and satisfaction with the family means satisfaction with life, which will consequently facilitate society’s growth, development, and material and spiritual progress (Abbaszadeh et al., 2024).

Empirical evidence has established that marital quality is associated with various factors, among which interpersonal forgiveness stands out. Interpersonal forgiveness is a positive intrapersonal and social change in response to an interpersonal transgression (Ouyang et al., 2019). This definition encompasses changes that may involve either a decrease in negative affect or a reduction of negative emotions coupled with an increase in positive emotions. In either case, this change represents a positive social change to foster more positive social interactions (Azimian et al., 2017). In line with this, Kaveh Farsani (2021) demonstrated that the variable of apology directly and indirectly affects the quality of marital relationships through the mediating role of emotional forgiveness and marital empathy.

On the other hand, research has shown that alexithymia in individuals affects their marital quality (Zakeri & Rezaei, 2022). Alexithymia is a psychological problem that hinders individuals’ well-being. When individuals are emotionally competent, they can enhance their mental health when facing life challenges (Shahmardi et al., 2022; Falahati & Mohammadi, 2020). Individuals who are deficient in identifying and appropriately applying their emotions may lack the ability to utilize their emotional world, leading to a decrease in positive emotions such as happiness and an increase in anxiety (Alexander et al., 2021). In this regard, Wells et al. (2016) established a significant relationship between alexithymia and its constituents (difficulty identifying emotions, difficulty describing emotions, and objective thinking) and perceived marital relationship quality.

Marital commitment significantly influences interpersonal forgiveness and emotional expression in married individuals and enhances marital quality (Nemati et al., 2022). A quality marriage includes key elements such as commitment, attraction, and understanding, among which marital commitment is the strongest and most stable predictor of marital quality and stability (Hou et al., 2019). Marital commitment entails a long-term perspective on marriage, willingness to sacrifice the relationship, preserving, strengthening, maintaining unity, and living with a spouse even when marriage does not bring rewards (Allen et al., 2022). In other words, marital commitment is a protective factor against marital breakdown and the most stable predictor of marital quality and stability (Aman et al., 2021). In line with this, Lin et al. (2022) found a significant association between marital commitment and quality in married men and women.

In general, problems arising in married individuals decline interpersonal and marital relationships, which in turn contributes to divorce among couples, which is the most acute and serious communication problem in families. Problems related to marital relations in nursing students who will form a considerable part of the treatment team soon can ultimately negatively affect patient care. Therefore, according to the above points and the importance of addressing the factors affecting the quality of marriage in this group of therapeutic strata, the present study investigated the mediating role of marital commitment in the relationship between interpersonal forgiveness, alexithymia, and marital quality in nursing students in Ahvaz City, Iran.

The most important hypotheses of this study are as follows:

1. There is a positive association between interpersonal forgiveness, marital quality, and marital commitment in nursing students.

2. There is a positive association between marital commitment and marital quality in nursing students.

3. There is a negative association between alexithymia and marital commitment in nursing students.

4. Forgiveness and alexithymia significantly indirectly affect marital quality through the mediating role of marital commitment.

Materials and Methods

The present study employed a descriptive correlational research design to examine the relationships between the variables within the structural equation modeling (SEM) framework. The target population comprised all nursing students at Ahvaz Islamic Azad University during the 2022-2023 academic year. A convenience sampling method was used to select the sample, and the research questionnaires were distributed among them. The inclusion criteria for the study were willingness to participate in the research, complete response to all questions, and being married for at least 1 year. The exclusion criterion was an incomplete response to the questions. In SEM, the sample size is calculated based on the number of direct paths, exogenous variables, and error variances. According to Kline’s (1998) suggestion, a sample size of 200 is sufficient, but considering the possibility of sample attrition, a sample size of 220 was considered. Ultimately, 204 samples thoroughly responded to the questionnaires and were included in the study.

Study instruments

Revised dyadic adjustment scale (RDAS)

The RDAS served as a brief measure of marital quality in this study. Developed by Busby et al. (1995), the RDAS features 14 items categorized into three subscales: consensus (items 1-6), satisfaction (items 7-10), and cohesion (items 11-14). All items utilize a 6-point Likert scale (0-5) except item 11, which employs a 5-point scale (0-4). Higher total scores (0-69) indicate greater marital quality. The Persian version of the RDAS has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, with a content validity index of 0.96 and a content validity ratio of 0.91, as Maroufizadeh et al. (2020) reported. Additionally, they documented a Cronbach α of 0.85 for the scale, indicating good internal consistency. In the present study, the scale’s internal consistency was estimated using the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.83.

Interpersonal forgiveness measurement questionnaire (IFMQ)

The IFMQ is a 25-item questionnaire developed by Ehteshamzadeh et al. (2011) to assess interpersonal forgiveness. It consists of three factors. Reconnection and revenge control (12 items) measures the individual’s willingness to reestablish a positive relationship with the transgressor and refrain from seeking revenge. Resentment control (6 items) assesses the individual’s ability to manage and reduce feelings of anger and resentment towards the transgressor. Finally, realistic understanding (7 items) measures the individual’s ability to understand the situation and the transgressor’s perspective from a realistic and non-judgmental standpoint. The IFMQ utilizes a 4-point Likert scale for scoring, with responses ranging from “strongly disagree”=1 to “strongly agree”=4. The total score for the entire scale ranges from 25 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of forgiveness. Items 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 25 are reverse-scored. The reliability of the Persian version of IFMQ was established by Ehteshamzadeh et al. (2011), who reported a Cronbach α of 0.80. In the present study, the internal consistency of the IFMQ was estimated using the Cronbach α coefficient, which was 0.86 for the total scale.

Toronto alexithymia scale (TAS)

The TAS is a 20-item self-report scale developed by Bagby et al. (2003) to assess alexithymia. It consists of three subscales. Difficulty identifying feelings subscale measures the individual’s difficulty recognizing and labeling emotions. Difficulty describing feelings subscale assesses the individual’s difficulty communicating emotions to others. Finally, the external-oriented thinking subscale measures individuals’ tendency to focus on external factors and events rather than their internal emotional states. The scale utilizes a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree) for item scoring. Scores ≤51 indicate low alexithymia, while scores ≥61 indicate high. Items 4, 10, 18, and 19 are reverse-scored. The total score for the scale is calculated by summing the scores of all items. The minimum and maximum TAS scores are 20 and 100, respectively. Internal consistency of the TAS was established by Bagby et al. (2003), who reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.81. Besharat et al. (2008) reported a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.75 for the Persian version of the scale, indicating acceptable internal consistency. In the present study, the internal consistency of the TAS was estimated using the Cronbach α coefficient, which was 0.82.

Dimensions of commitment inventory (DCI)

The DCI is a 44-item questionnaire developed by Adams & Jones (1997) to measure three dimensions of marital commitment. The personal commitment dimension assesses the individual’s commitment to their spouse based on their perceived attractiveness and personal qualities. The moral commitment dimension measures the individual’s commitment to marriage based on their belief in the sanctity and importance of the marital relationship. Finally, the structural commitment dimension assesses the individual’s commitment to their spouse and marriage based on feelings of obligation, pressure to continue the marriage, and fear of the consequences of divorce. The DCI is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1: Strongly disagree to 5: Strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of commitment. The total score for the questionnaire is calculated by summing the scores of all items. The highest and lowest possible scores are 220 and 44, respectively. A score closer to 220 indicates high commitment, while a score closer to 44 indicates low commitment. Adams & Jones (1997) further reported the reliability of the DCI subscales, with Cronbach α coefficients ranging from 0.86 to 0.91. Mortezaei & Rezazade (2021) established the reliability of the Persian version of the inventory with a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.85. In the present study, the internal consistency of the DCI was estimated using the Cronbach α coefficient, which was 0.84.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using a combination of descriptive and inferential techniques. Descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD, were employed to characterize the distribution of the research variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient was utilized to assess the relationships between the variables. SEM was also implemented to examine the hypothesized relationships within a comprehensive framework. Analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 27 for initial data exploration and AMOS software, version 24.0 for SEM analysis.

Results

The subjects comprised 204 nursing students with a mean age of 26.87±6.40 years. Of the participants, 148(72.55%) were female and 56(27.45%) were male. The Mean±SD of the study variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 also shows the Pearson correlation coefficients between the study variables. Statistically significant correlations were found between marital quality and forgiveness (r=0.62, P<0.01), marital quality and commitment (r=0.67, P<0.01), and alexithymia and forgiveness (r=-0.38, P<0.01). These correlations indicate that higher levels of forgiveness and commitment are associated with better marital quality, while higher levels of alexithymia are associated with lower marital quality. An initial preliminary model was developed to explain marital quality based on interpersonal forgiveness, alexithymia, and marital commitment, as shown in Figure 1.

Based on the data in Table 2, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) index was 0.083, indicating that the initial model needed to be modified.

After removing one of the paths (alexithymia to marital quality) in the final model, the RMSEA index was 0.071, indicating a good fit for the model. The final modified model is presented in Figure 2.

Table 3 presents the findings related to the path coefficient estimates for both direct and indirect relationships. The study yielded significant results regarding the relationships between forgiveness, emotional expression (measured by alexithymia), marital commitment, and marital quality in nursing students. The findings revealed that interpersonal forgiveness strongly correlated with marital quality and commitment (P<0.001), supporting the first hypothesis. Similarly, marital commitment demonstrated a positive and significant correlation with marital quality (P<0.001), confirming the second hypothesis. Alexithymia exhibited a negative and significant association with marital commitment (P<0.001), supporting the third hypothesis. However, it did not directly impact marital quality. Interestingly, both forgiveness and alexithymia demonstrated significant indirect effects on marital quality through the mediating role of marital commitment (P<0.001). This finding aligns with the fourth hypothesis.

Discussion

The present study investigated the mediating role of marital commitment in the relationship between interpersonal forgiveness, alexithymia, and marital quality in nursing students. The first finding indicates a significant relationship between interpersonal forgiveness and marital quality. This finding is consistent with the study’s results by Fatehi et al. (2021).

One possible explanation for this finding is that admitting mistakes and apologizing in close relationships lead to interpersonal forgiveness, reducing distress, anger, and revenge. Interpersonal forgiveness can help reduce destructive behaviors that stem from injustice, and increasing empathy and compassion can enhance interpersonal forgiveness in the relationship. Spouses who can engage in the relationship repair cycle are more effective in preventing the effects of damage to the relationship and maintaining or increasing marital quality in the face of events (Brandão et al., 2020). Interpersonal forgiveness is defined as a positive interpersonal and social change in response to a transgression that occurs in the interpersonal realm. According to this definition, interpersonal forgiveness encompasses changes that can be accompanied by a decrease in negative emotions or a decrease in negative emotions along with an increase in positive emotions. Given the role of interpersonal forgiveness in reducing negative and increasing positive emotions, it can be seen that interpersonal forgiveness is associated with high marital quality (Fatehi et al., 2021). When an individual is capable of interpersonal forgiveness, the relationship between the violation, marital quality, and marital satisfaction is weakened. Individuals capable of forgiving their spouse interpersonally believe in the sanctity of their marital relationship, and this ability to forgive their spouse interpersonally leads to greater strength in marital quality and increased marital quality satisfaction.

The results show that the relationship between alexithymia and marital quality in nursing students is not significant. This finding is inconsistent with the results of the study by Hashemi (2021). It can be argued that in the mentioned study, the relationship between alexithymia and marital quality was examined using correlation and regression tests, and this relationship was found to be significant. In contrast, the hypotheses were tested using SEM in the present study. The relationship between alexithymia and marital quality was also significant based on the Pearson test. Still, in the model, due to the presence of a mediator variable, the total variance and effect of alexithymia on marital quality were explained through the mediator variables or the indirect relationship. In other words, in this model, alexithymia still affects marital quality, but indirectly. One possible explanation for this finding is that individuals who can recognize their emotions and effectively express their emotional states are better able to cope with life’s problems and are more successful in adapting to the environment and others.

In contrast, individuals with alexithymia experience confusion and helplessness in the cognitive processing, perception, and evaluation of emotions due to their inability to identify and regulate emotions. This inability can disrupt their emotional and cognitive organization and make successful adaptation difficult (Zakeri & Rezaei, 2022). As a result, the couple’s relationships become conflicted, boring, and lacking in intimacy, reducing marital quality. This is because romantic and satisfying relationships require the ability to identify and express emotions to one’s partner. Therefore, alexithymia in couples predicts marital conflicts (Hashemi, 2021).

The results also show that the relationship between marital commitment and quality is statistically significant. This finding is consistent with the study’s results by Moghimi et al. (2022). One possible explanation for this finding is that a strong commitment and dedication between partners can improve their marital quality. When both individuals respond positively to the challenges of their lives together with confidence and determination, a sense of security and strength in their relationship is strengthened. The time and effort required to solve the problems and concerns of the relationship play a significant role in increasing the quality of marital life (Aman et al., 2021). Additionally, accepting the relationship’s shortcomings and challenges can contribute to individual and relationship growth. Moreover, maintaining strong and sincere emotional feelings between both individuals in the marital relationship can be the key to happiness and well-being in this sensitive relationship.

The results show that the relationship between interpersonal forgiveness and marital quality is significant, with marital commitment as a mediator. Additionally, the results indicate that the relationship between alexithymia and marital quality is significant, with marital commitment as a mediator. No similar study was found regarding these findings, and this research is the first to examine the variables included in this hypothesis. Orathinkal and Vansteenwegen (2006) found a positive association & forgiveness and general life adjustment, suggesting that individuals with higher levels of forgiveness may experience better overall adjustment in various life domains. Moreover, Braithwaite et al. (2011) reported that forgiveness could lead to happier relationships through increased effort and less fighting. There was a significant and direct association between interpersonal forgiveness and marital quality. The results also show that interpersonal forgiveness increases marital quality in nursing students by increasing marital commitment. Interpersonal forgiveness is a crucial factor in enhancing marital quality. This forgiveness can contribute to marital commitment in married life and consequently improve the family’s overall functioning and marital relationship (Orathinkal and Vansteenwegen, 2006).

The results show that interpersonal forgiveness positively correlates to marital commitment in this group. Building upon Tsang et al.’s (2006) work, our findings add to the multifaceted influence of forgiveness on marital quality. While they identified revenge and benevolence as dimensions of forgiveness that promote later closeness and commitment, our study suggests a more complex interplay. Here, forgiveness as a whole, encompassing its various dimensions, positively influences these aspects of marital quality. In more precise terms, married individuals with higher levels of interpersonal forgiveness, as a mastery and complete and acceptable understanding of their spouse’s needs, show higher marital commitment to their spouse. The direct relationships show that alexithymia lacks a significant relationship with marital quality. The relationship between alexithymia, marital quality, and marital commitment in nursing students is an important issue, indicating the connection between an individual’s emotional and mental state and their marital life functions. Unpleasantness in couples’ relationships may be due to the inability to establish healthy and proper communication with the spouse, the inability to solve family problems, lack of commitment to the marital relationship, incorrect thinking about the challenges of married life, and so on (Lin et al., 2022; Stanley et al., 2010). Additionally, deficiencies in marital interactions can lead to behavioral disorders (negative interactions, emotional dryness, hidden resentment) (Irani et al., 2022). Therefore, marital commitment adequately plays the role of a mediating variable in the relationship between interpersonal forgiveness and alexithymia with marital quality.

Conclusion

This study examined the interplay between interpersonal forgiveness, alexithymia, marital commitment, and marital quality in nursing students. The findings supported our hypotheses, revealing positive associations between forgiveness and marital quality and commitment. Additionally, marital commitment emerged as a significant positive predictor of marital quality, underlining its critical role in marital satisfaction. Interestingly, while alexithymia exhibited a negative correlation with marital commitment, it did not directly impact marital quality. However, the indirect effects analysis revealed a significant mediating role for marital commitment. Specifically, alexithymia indirectly reduces marital quality by decreasing marital commitment. These findings suggest that marital commitment is a crucial mediator in linking forgiveness and alexithymia to marital quality. In simpler terms, nursing students with higher levels of forgiveness and lower levels of alexithymia tend to report better marital quality, primarily because these factors contribute to stronger marital commitment. This study paves the way for further investigations into the complex dynamics of marital relationships. Future studies could explore the potential mechanisms underlying the link between forgiveness and marital commitment. For instance, research could examine how forgiveness fosters positive communication or emotional responsiveness within the relationship, ultimately leading to stronger commitment. Additionally, investigating interventions to improve emotional expression skills and their potential impact on marital quality and commitment would be a valuable contribution to the field.

This study’s limitations include using self-report instruments, which may be susceptible to social desirability bias in the participants’ responses. Additionally, the sample restriction to nursing students in Ahvaz necessitates caution in generalizing the results to other married individuals in different cities.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1402.078). After a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, and potential risks and benefits, all subjects provided written informed consent. Additionally, permission to recruit the samples was obtained from the relevant faculty authorities at the university.

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Nasrin Eftekhari Moghaddam, approved by the Department of Psychology, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design and project administration: Nasrin Eftekhari Moghaddam, and Masoud Shahbazi; Data acquisition: Nasrin Eftekhari Moghaddam; Data analysis, interpretation and writing the original draft: Kobra Kazemian Moghaddam and Masoud Shahbazi; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Abbaszadeh, R., et al., 2024. A cross-sectional comparative study of nurses’ and family members’ perceptions on priority and satisfaction in meeting the needs of family members at the Emergency Department. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 50(2), pp. 215-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.jen.2023.10.003] [PMID]

Adams, J. M. & Jones, W. H., 1997. The conceptualization of marital commitment: An integrative analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(5), pp. 1177-96. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.72.5.1177]

Alexander, R., et al., 2021. The neuroscience of positive emotions and affect: Implications for cultivating happiness and well-being. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 121, pp. 220-49. [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.12.002] [PMID]

Allen, S., et al., 2022. Day-to-day changes and longer-term adjustments to divorce ideation: Marital commitment uncertainty processes over time. Family Relations, 71(2), pp. 611-29. [DOI:10.1111/fare.12599]

Aman, J., et al., 2021. Religious affiliation, daily spirituals, and private religious factors promote marital commitment among married couples: Does religiosity help people amid the COVID-19 crisis?. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, pp. 657400. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.657400] [PMID]

Azimian, J., et al., 2017. Investigation of marital satisfaction and its relationship with job stress and general health of nurses in Qazvin, Iran. Electronic Physician, 9(4), pp. 4231-7. [DOI:10.19082/4231]

Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D. & Taylor, G. J., 1994. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale--I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38(1), pp. 23-32. [DOI:10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1] [PMID]

Besharat, M. A., 2008. Assessing reliability and validity of the Farsi version of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale in a sample of substance-using patients. Psychological Reports, 102(1), pp. 259-70. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.102.1.259-270] [PMID]

Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A. & Fincham, F. D., 2011. Forgiveness and relationship satisfaction: Mediating mechanisms. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(4), pp. 551-9. [DOI:10.1037/a0024526] [PMID]

Brandão, T., et al., 2020. Dyadic coping, marital adjustment and quality of life in couples during pregnancy: An actor-partner approach. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 38(1), pp. 49-59. [DOI:10.1080/02646838.2019.1578950] [PMID]

Busby, D. M., et al., 1995. A revision of the dyadic adjustment scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: Construct Hierarchy and Multidimensional Scales. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 21(3), pp. 289-308. [DOI:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1995.tb00163.x]

Ehteshamzadeh, P., et al., 2011. Construct and validation of a scale for measuring interpersonal forgiveness. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 16(4), pp. 443-55. [Link]

Falahati, F. & Mohammadi, M., 2020. Prediction of marital burnout based on automatic negative thoughts and alexithymia among couples. Journal of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, 8(2), pp. 2211-19. [DOI:10.22038/jmrh.2020.43917.1522]

Fatehi, N., Gholami Hosnaroudi, M. & Abed, N., 2021. [The mediating role of marital forgiveness and mental well-being in the relationship between mindfulness and sexual satisfaction in married women and men of Tehran City: A descriptive study (Persian)]. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, 20(6), pp. 660-45. [DOI:10.52547/jrums.20.6.660]

Gharibi, M., Sanagouymoharer, G. & Yaghoubinia, F., 2015. The relationship between quality of life with marital satisfaction in nurses in social security hospital in Zahedan. Global Journal of Health Science, 8(2), pp. 178-84. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v8n2p178]

Hashemi, Z., 2021. [The relationship between Alexithymia and relationship quality in women with general anxiety disorder claiming divorce (Persian)]. Quarterly Journal of Woman and Society, 11(44), pp. 271-88. [Link]

Hou, Y., Jiang, F. & Wang, X., 2019. Marital commitment, communication and marital satisfaction: An analysis based on actor-partner interdependence model. International Journal of Psychology: Journal International de Psychologie, 54(3), pp. 369-76. [DOI:10.1002/ijop.12473] [PMID]

Irani, E., Park, S. & Hickman, R. L., 2022. Negative marital interaction, purpose in life, and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older couples: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. Aging & Mental Health, 26(4), pp. 860-9.[DOI:10.1080/13607863.2021.1904831] [PMID]

Jeffreys, M. R., 2022. Nursing student retention and success: Action innovations and research matters. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 17(1), pp. 137-46. [DOI:10.1016/j.teln.2021.06.010]

Kaveh Farsani, Z., 2021. [Evaluating the model investigating the relationship between apology and the marital relationships quality: the mediating of marital empathy and emotional forgiveness (Persian)]. Biannual Journal of Applied Counseling, 10(2), pp. 51-72. [Link]

Kline, R. B., 2005. Principals and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press. [Link]

Lin, L., et al., 2022. Research on the relationship between marital commitment, sacrifice behavior and marital quality of military couples. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, pp. 964167. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.964167] [PMID]

Maroufizadeh, S., et al., 2020. The Persian version of the revised dyadic adjustment scale (RDAS): A validation study in infertile patients. BMC Psychology, 8(1), p.p. 6. [DOI:10.1186/s40359-020-0375-z] [PMID]

Mazhari, R., Farhangi, A. & Naderi, F., 2022. The relationship between psychological vulnerability and psychological capital and health anxiety through the mediating role of emotional processing in nurses working in the COVID-19 units. Journal of Client-centered Nursing Care, 8(3), pp. 167-76. [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.8.3.429.1]

Moghimi, S., et al., 2022. [Development of a causal model of marital commitment based on forgiveness and differentiation mediated by marital intimacy and the effectiveness of this model on the quality of marital relationships (Persian)]. Shenakht Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 9(2), pp. 146-59. [DOI:10.32598/shenakht.9.2.146]

Mortezaei, N. & Rezazade, S. M., 2021. [The mediating role of marital commitment in the relationship between equity and marital satisfaction (Persian)]. Journal of Applied Psychological Research, 11(4), pp. 281-92. [Link]

Nemati, M., et al., 2022. Marital commitment and mental health in different patterns of mate selection: A comparison of modern, mixed, and traditional patterns. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 17(4), pp. 418-27. [DOI:10.18502/ijps.v17i4.10691] [PMID]

Orathinkal, J. & Vansteenwegen, A., 2006. The effect of forgiveness on marital satisfaction in relation to marital stability. Contemporary Family Therapy, 28(2), pp. 251-60. [DOI:10.1007/s10591-006-9006-y]

Orszulak, N., et al., 2022. Nurses’ quality of life and healthy behaviors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), pp. 12927. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph191912927]

Ouyang, Y. Q., et al., 2019. A Web-based Survey of Marital Quality and job satisfaction among Chinese Nurses. Asian Nursing Research, 13(3), pp. 216-20. [DOI:10.1016/j.anr.2019.07.001]

Shahmardi, S., Pourebrahim, T. & Hoobi, M. B., 2022. The role of family emotional atmosphere and attachment styles in alexithymia of married people. Journal of Client-centered Nursing Care, 8(4), pp. 273-80. [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.8.4.449.1]

Siadat, F., et al., 2023. Relationship between attachment behaviors and marital trust among nurses with the mediating role of covert aggression. Journal of Client-centered Nursing Care, 9(1), pp. 79-88. [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.9.1.485.1]

Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K. & Whitton, S. W., 2010. Commitment: Functions, formation, and the securing of romantic attachment. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2(4), pp. 243-57. [DOI:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00060.x]

Tsang, J. A., McCullough, M. E. & Fincham, F. D., 2006. The longitudinal association between forgiveness and relationship closeness and commitment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25(4), pp. 448-72. [DOI:10.1521/jscp.2006.25.4.448]

Wells, R., Rehman, U. S. & Sutherland, S., 2016. Alexithymia and social support in romantic relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, pp. 371-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.029]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2024/03/22 | Accepted: 2024/07/2 | Published: 2024/11/1

Received: 2024/03/22 | Accepted: 2024/07/2 | Published: 2024/11/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |