Tue, Dec 2, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 11, Issue 2 (Spring 2025)

JCCNC 2025, 11(2): 161-172 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Okinarum G Y, Ceria I. Indonesian Fathers’ Perceptions of Maternal Healthcare During the Perinatal Period. JCCNC 2025; 11 (2) :161-172

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-721-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-721-en.html

1- Department of Midwifery Professional Education Program, Faculty of Health Science, Universitas Respati Yogyakarta, Depok, Indonesia. , gitaokinarum@respati.ac.id

2- Midwifery Study Program, Faculty of Health Science, Universitas Respati Yogyakarta, Depok, Indonesia.

2- Midwifery Study Program, Faculty of Health Science, Universitas Respati Yogyakarta, Depok, Indonesia.

Full-Text [PDF 633 kb]

(703 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1477 Views)

Full-Text: (383 Views)

Introduction

The perinatal phase, encompassing pregnancy through postpartum, is a critical, demanding, and distinctive period in a woman’s life. The mental and physical well-being of women significantly influences fetal health, successful vaginal delivery, and nursing (Firouzan et al., 2018, Firouzan et al., 2019). The International Conference on Population and Development and the Fourth World Conference on Women emphasized the advantage of the father’s role in reproductive health and women’s rights (Singh et al., 2014), while Lewis et al. (2015) championed this as a human rights imperative. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that a mother dies every 2 minutes due to complications related to pregnancy and delivery (WHO, 2016b; WHO, 2016a); nevertheless, 99% of these fatalities are preventable (King, 2013). The WHO characterizes fathers’ involvement in the safe motherhood program as enhancing access to perinatal care, promoting awareness, and engaging in childbirth preparation initiatives. Mothers who get spousal support throughout pregnancy experience enhanced empowerment in managing stress and challenges, demonstrate improved tolerance during childbirth, and adapt more readily to their children postnatally (Kortsmit et al., 2020; Tohotoa et al., 2011).

Australia, a prosperous nation, conducted a study that found a significant correlation between paternal engagement in middle- and low-income countries and maternal mortality after childbirth (Davis et al., 2012). Moreover, supplementary research indicates that paternal involvement positively influences the reduction of smoking and alcohol consumption, the risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, intrauterine growth restriction, and infant mortality (Forbes et al., 2021). The willingness of fathers to contribute to maternal health has increased in recent years. Yet, few countries have enacted legislation acknowledging fathers’ contributions to maternal, infant, and child health. Research demonstrates that, despite such policies, implementation is deficient in these domains since men are frequently marginalized from formulating and administering participation initiatives in maternal health (Gopal et al., 2020).

In Indonesia, a developing nation characterized by a robust patriarchal culture, the involvement of fathers during the perinatal period is atypical. There is a favorable perception of enhanced paternal participation in women’s health and social welfare throughout the perinatal period. Nonetheless, when examining the perspectives of individuals and recipient groups regarding gender roles across various cultures, it is imperative to acknowledge their delicate nature. Qualitative research identifies, describes, and conceptualizes participant experiences, thus enhancing comprehension and knowledge of fathers’ roles in supporting women during pregnancy and the postnatal period. Researchers frequently employ this method to elucidate concepts and their interrelations (Creswell & Poth, 2017). This qualitative study sought to explore fathers’ perspectives and experiences regarding maternal health care throughout the perinatal period in Indonesia. We conducted this study on a national scale to optimize benefits for end users, specifically by establishing a framework for enhancing maternal strength during the perinatal period. The study team consists of midwives specializing in community midwifery, which is closely associated with empowering parents to improve perinatal health.

Materials and Methods

Design, setting, and participants

This study employed a qualitative research method, including a descriptive qualitative design and a content analysis approach. The participants included 30 fathers from 8 Indonesian provinces: South Sumatra, DKI Jakarta, West Java, DI Yogyakarta, East Java, East Kalimantan, Bali, and West Nusa Tenggara. We distributed the call to participants online via social media. Fathers whose wives are in the perinatal phase, fathers who are physically and emotionally healthy, eager to participate in the study process from start to finish, have reliable internet access, and might operate Zoom meetings are all eligible.

Data collection

Three focus group discussions (FGDs) (each with 10 participants) were conducted online using the Zoom meeting platform. The study data were collected from May to June 2024. Each session lasted approximately 60 minutes. It began with an open question: “How can fathers participate in caring for their wives during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum?” “Please explain!” As the FGD advanced, the author generated more specific inquiries based on the interview framework, such as “do you feel at ease participating in maternal healthcare during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period?” and “Are there any barriers that inhibit your involvement in maternal health care? Participants’ comments and discussions raised further questions and guided the interviews. The researcher and a midwife specializing in qualitative research continued facilitating the FGDs by employing probing questions to achieve the research objectives. All participants showed similar responses and patterns across the 3 focus group sessions, and concurrent data analysis did not result in new categories that would indicate data saturation. In addition, the study utilized a homogeneous group with well-defined objectives, contributing to data saturation (Hennink & Kaiser, 2022).

Data analysis

We evaluated the data using conventional content analysis and NVivo software, version 14 to manage the data. The interviews were conducted in Indonesian, recorded using Zoom Meeting technology, and saved in the cloud. The materials were reread many times to ensure a thorough grasp of the content. The author conducted data analysis simultaneously with the FGDs, following the established methodology of Graneheim and Lundman (2004). TheFGDs were transcribed verbatim and were reviewed multiple times to derive primary codes. The analogous primary codes were combined to form broader categories based on their similarities and differences, ultimately extracting latent concepts from the data (Schwandt et al., 2007).

Rigor and trustworthiness

This study employed references from Lincoln and Guba (1985) to demonstrate the data’s credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. To enhance credibility, the participants were drawn from 8 provinces in Indonesia, spanning both western and central Indonesian time. This criterion led to varying interview times due to a one-hour time difference between researchers in central and west Indonesia. Prolonged engagement with participants facilitated trust and produced more comprehensive data. After establishing the categories, the researcher employed member checks. We recalibrated and amended any categories and subcategories that conflicted with the participants’ perspectives. We endeavored to thoroughly elucidate the research context and participants’ perspectives regarding transferability. To ensure dependability, four specialists in qualitative research (a midwife, a nutritionist, an academician, and a gender-responsive expert) evaluated and verified the research methodology and data analysis to confirm that the results were consistent and replicable. An independent reviewer validated the research methodology and data interpretation to ensure confirmability.

Results

Participants’ profile

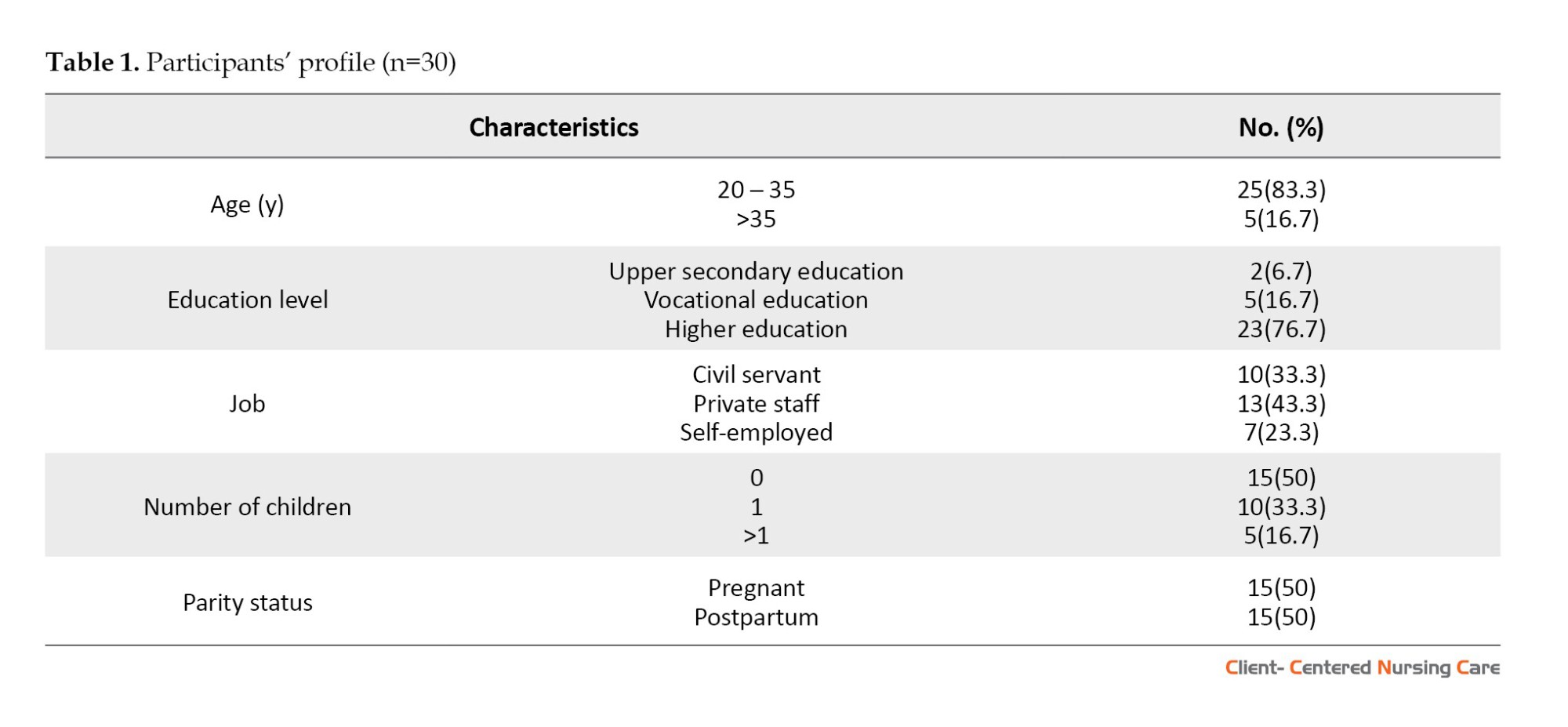

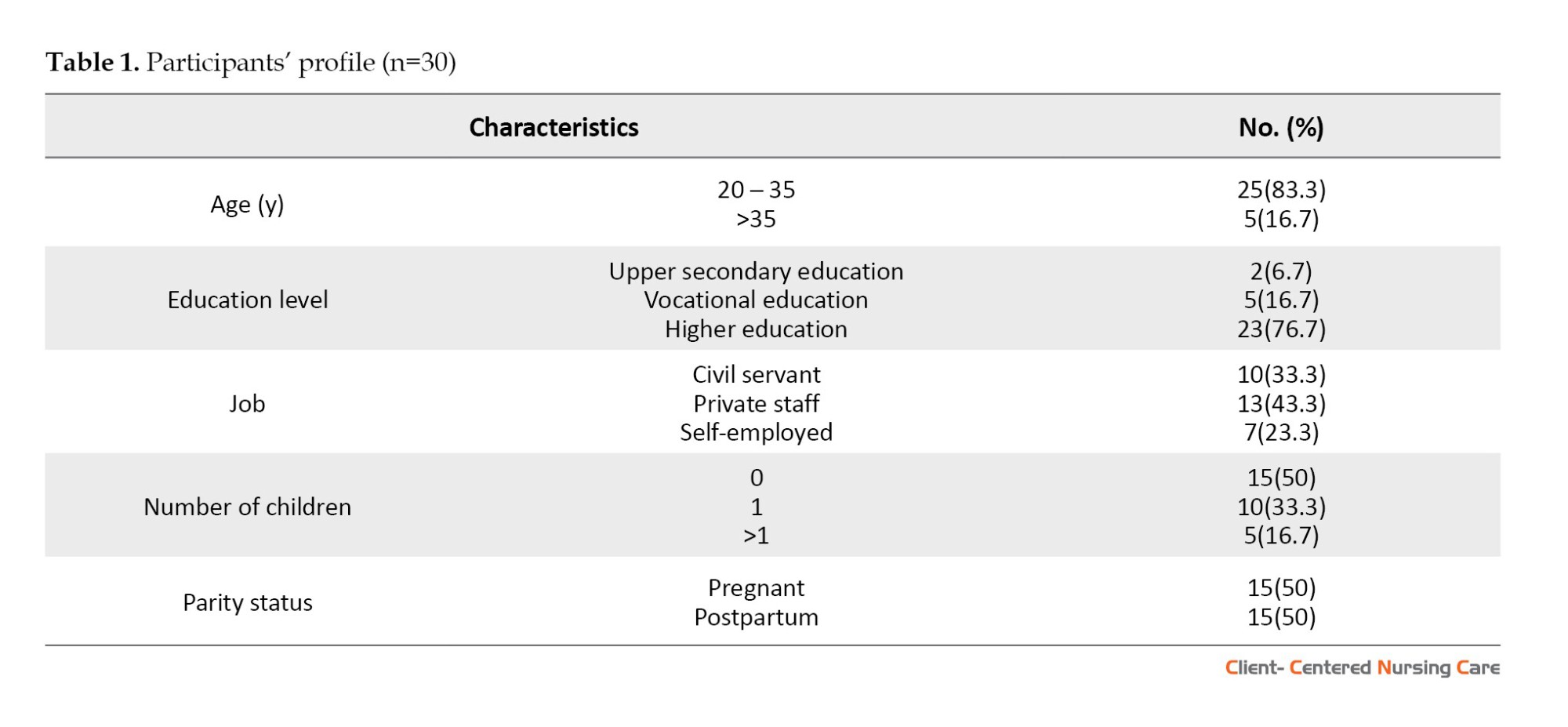

This study included 30 father participants, primarily aged 25-35, from 8 provinces in Indonesia. Each participant had one or more children and earned a salary above the minimum, as detailed in Table 1.

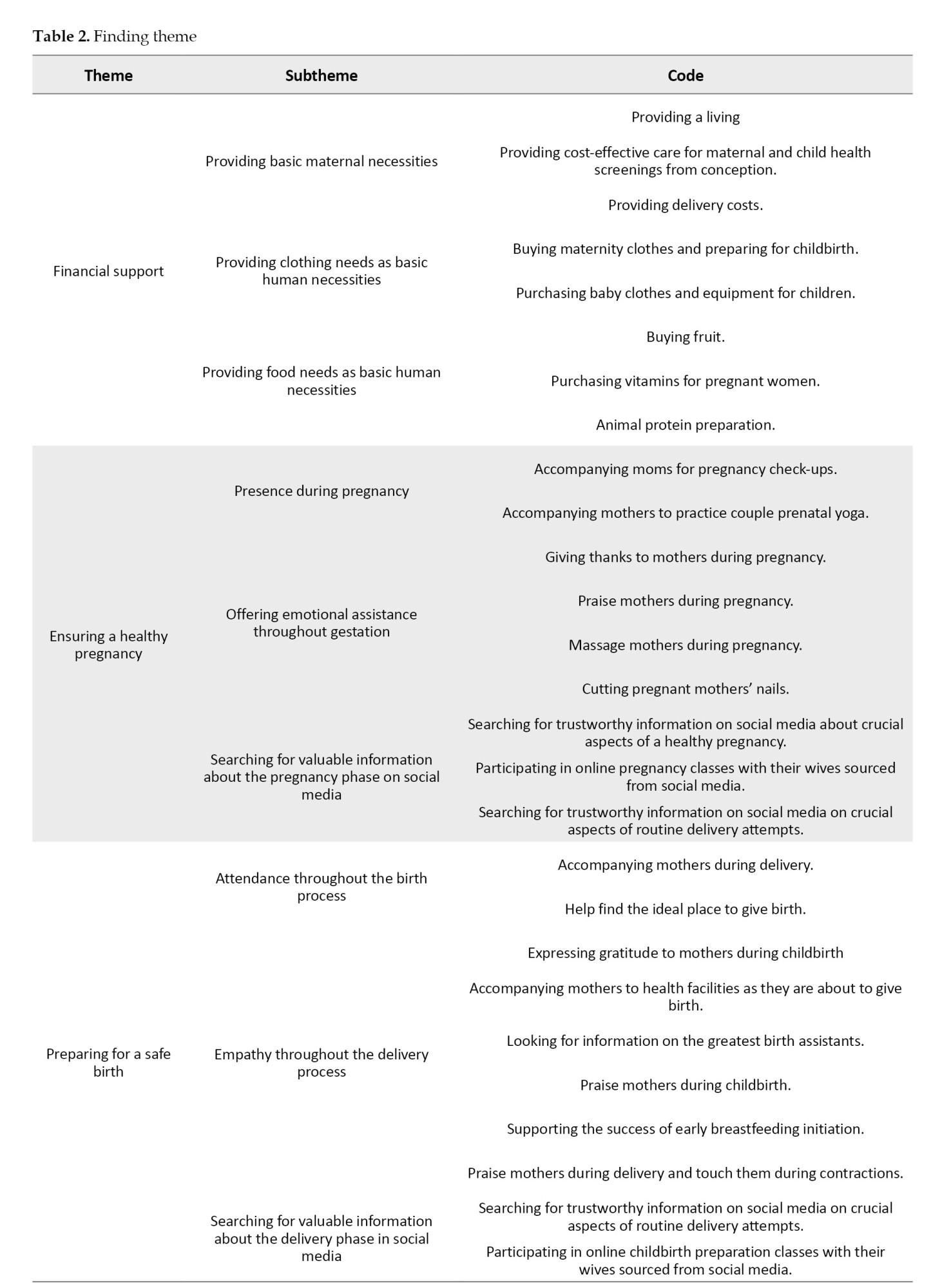

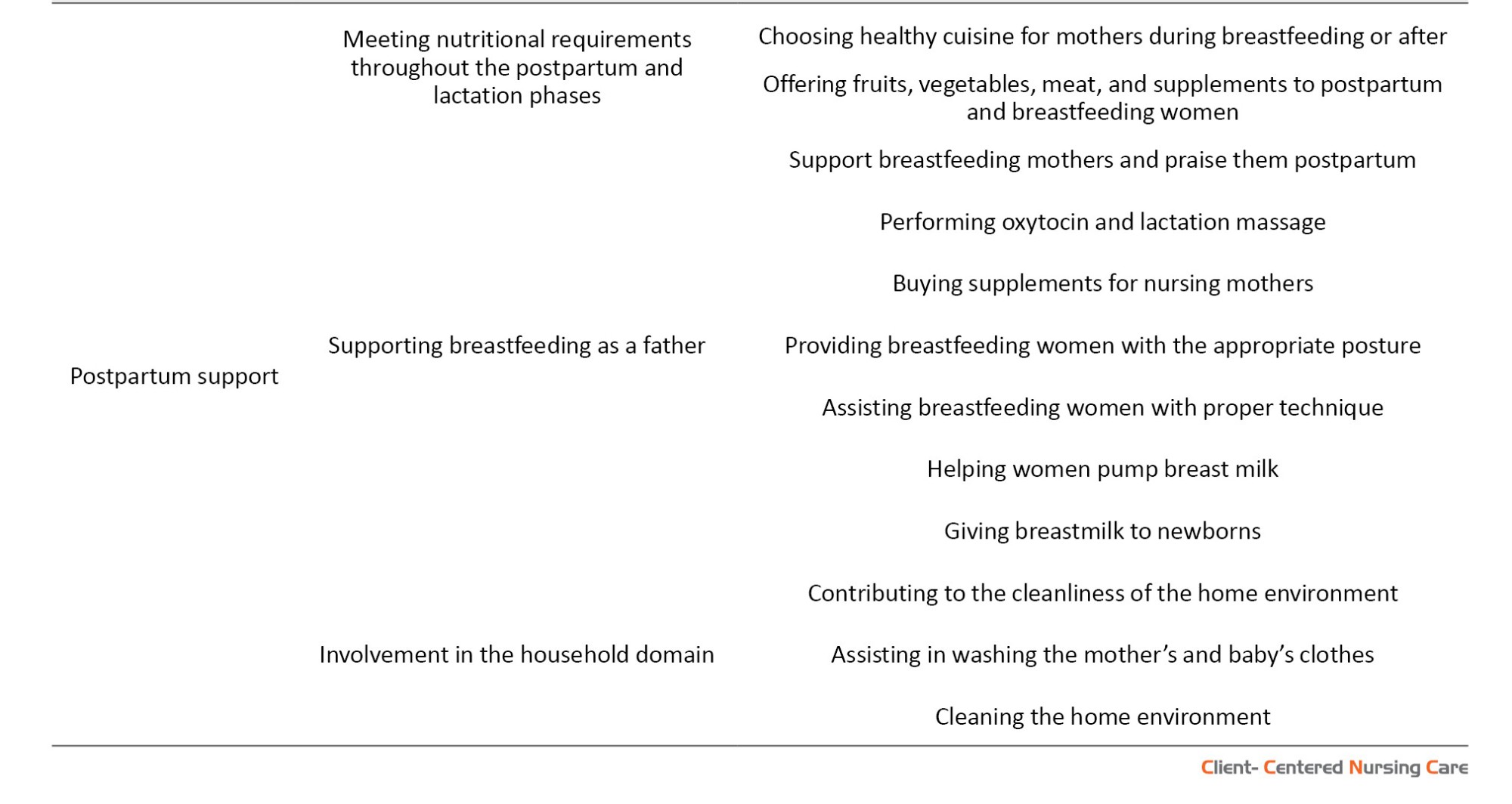

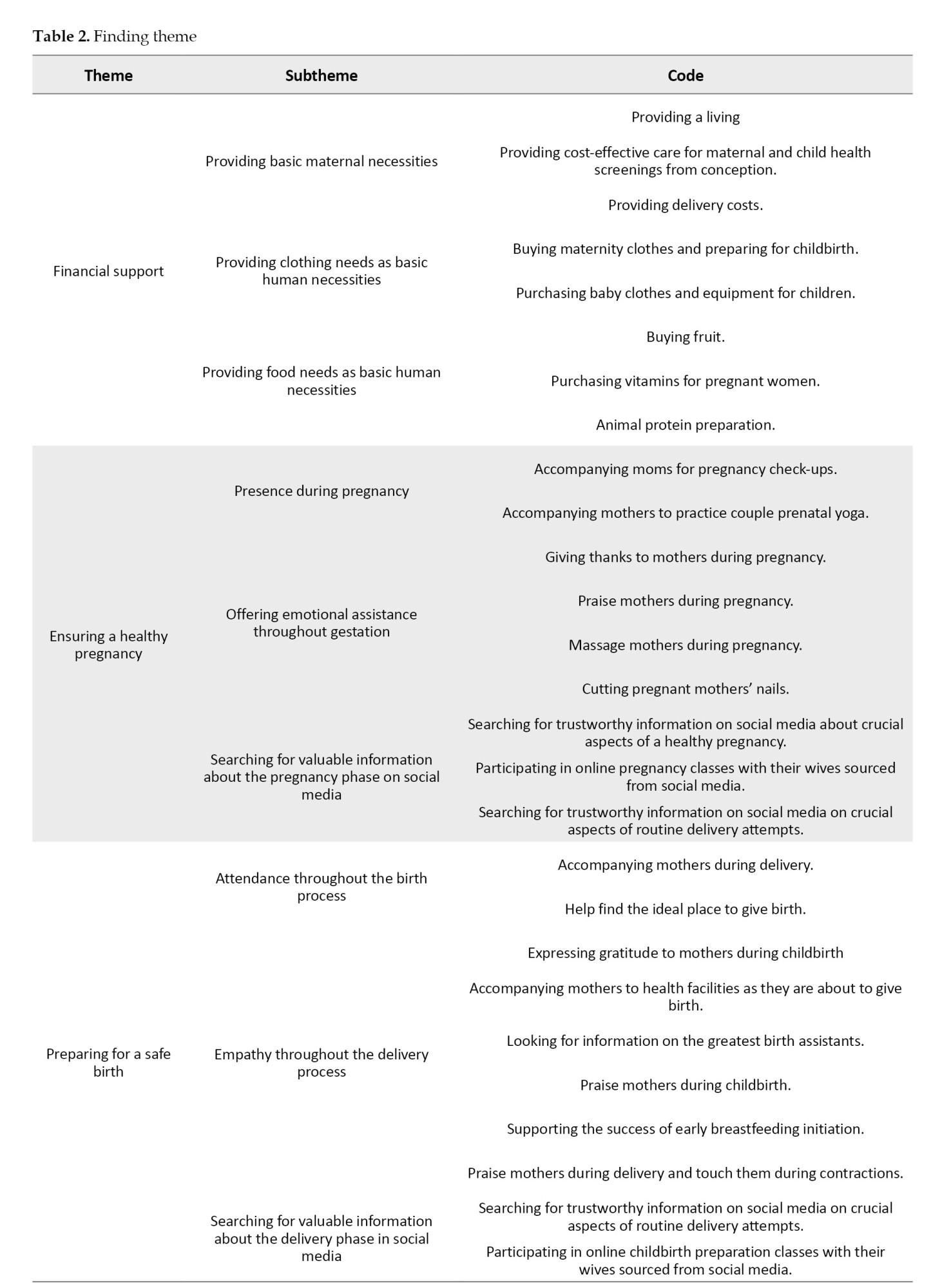

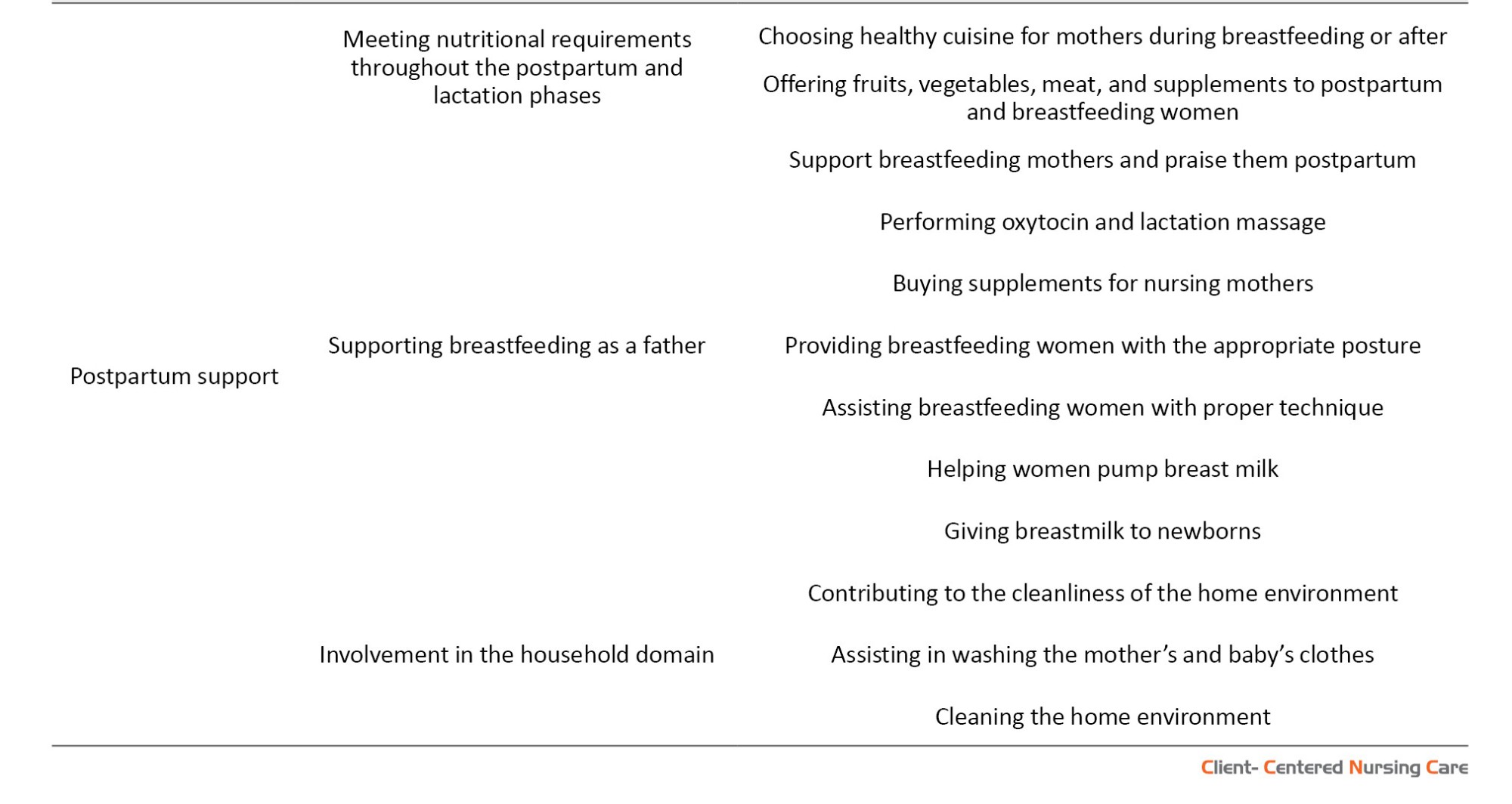

Four main themes emerged from the data, indicating how fathers are involved in maternal and child health care during the perinatal period in Indonesia: Financial support, ensuring a healthy pregnancy, preparing for a safe birth, and postpartum support (Table 2).

Financial support

The first theme indicates that paternal engagement in addressing financial support is crucial for maternal and child health care, as it necessitates fathers to comprehend and meet the mother’s and child’s essential requirements, such as clothes and nutrition. During the FGDs, the participants indicated that support in meeting the maternal primary needs demonstrates their preparedness as fathers:

“As a spouse and parent, I have the responsibility of sustaining the family’s financial well-being. As fathers and husbands, we must prepare ourselves” (FGD 1).

“Monthly pregnancy check-ups are quite costly. Nonetheless, the paramount concern is the health of my wife and child; so, with divine providence, a solution may emerge” (FGD 1).

“My financial circumstances are below average, and I am confident that the men here possess varying financial capacities. It is our duty as men to provide for our wives and children. The capacity to honor agreements influences a man’s self-worth” (FGD 3).

Ideally, fathers should assume responsibility for meeting fundamental maternal requirements, including the provision of clothing and food. Financial considerations significantly influence the enhancement of prenatal and postnatal services, as articulated by participants in the FGD. Meeting dietary needs during pregnancy is crucial for women and their children’s health. Interventions for fathers, such as supplying fruit, vegetables, and meat, are the most effective steps made for mothers throughout pregnancy.

“I keep stocks of fruit, vegetables, meat, and nutritious food in the refrigerator.”

“Usually, at every pregnancy check-up, there are supplements and vitamins prescribed by a midwife or doctor, so I provide them.”

“Currently, I am responsible for the financial expenses associated with purchasing maternity attire, complete outfits, and necessary equipment for childbirth while my wife makes the purchases. I also incur the expense of prenatal vitamins and endeavor to meet my wife’s nutritional needs by supplying balanced, nutritious cuisine” (FGD 2).

Ensuring a healthy pregnancy

The father’s involvement and presence during pregnancy are crucial in promoting maternal health. Participants in the FGD indicated that the husband’s presence during prenatal check-ups is crucial for providing the mother with support and attention. Pregnant women require financial assistance and spousal support during prenatal examinations and fitness activities, such as couples’ prenatal yoga, creating comfort and security.

“I consistently accompany my wife to her prenatal check-ups and enter the examination room at the polyclinic to ascertain the health of both my wife and the fetus. I often accompany my wife to prenatal yoga sessions. (FGD 1, FGD 2, and FGD 3).

Fathers assume partnership roles with pregnant women in their households, necessitating the involvement of both sides. The active participation of dads in household tasks, such as dishwashing and cleaning, disrupts the cycle of patriarchy. The psychological interaction will positively influence the health of pregnant women.

“In the first trimester, my wife experienced terrible diarrhea; I found it distressing to witness her condition, and the doctor indicated a risk of miscarriage, prompting me to advise her to rest and refrain from household chores. On multiple occasions, I assumed responsibility for or employed a housemaid” (FGD 3).

A father’s commendation of a mother during gestation exemplifies the essential emotional support required. A father’s vocal engagement immediately enhances the mother’s happiness, boosting her psychological adaptability during pregnancy.

“I once participated in a prenatal yoga class with a couple, where the instructing midwife highlighted the significance of attention and commendation for pregnant women, as it can enhance their mood” (FGD 1).

The woman endured back and waist pain during her pregnancy as a result of physiological adaptation. The father’s gentle massage demonstrated a necessity for empathy.

“I provided my wife with a soothing massage during her pregnancy. Nevertheless, for specialized care, I typically engage a pregnant massage therapist” (FGD 1 & FGD 2).

“My wife expressed difficulty in trimming her nails due to her large abdomen and swollen feet, prompting me to assist her” (FGD 3).

Utilizing social media proficiently can assist fathers in enhancing their analytical and critical thinking abilities, thereby ensuring a secure pregnancy for their spouses.

“I monitor social media for the latest updates about my wife’s pregnancy. I also endeavor to exclude invalid material. Presently, information from physicians and midwives actively creating social media content is beneficial. This could potentially help us, as non-experts, better understand the misconceptions and reality surrounding pregnancy” (FGD 1 & FGD 2).

“I accompany my wife to online pregnancy classes sourced from social media to obtain accurate information” (FGD 3).

Preparing for a safe delivery

Participants in the FGDs asserted that guaranteeing a safe delivery is their obligation. This factor signifies their preparedness to receive the arrival of their baby. The father’s presence and empathy during birth are vital to the mother and child’s health.

“From the beginning, I played a role in finding the best place to give birth, of course for the health and safety of my wife and child” (FGD 1).

“ I received full assistance from my workplace throughout the delivery. Fortunately, I was able to take leave” (FGD 2).

“The key is to make my wife happy, so I keep praising her, ‘good honey, you’re good at pushing honey,’ stroking her back and waist. I kiss her forehead and chant prayers in her ear; that way, my wife is enthusiastic” (FGD 3).

“From the start, I left everything to my wife; of course, she knows what is best, and I completely support her decision to give birth. The most essential thing to me is the safety of my wife and child. I completely support newborns that breastfeed themselves (read: Early breastfeeding initiation), and my responsibility is always to be there to accompany my wife, who is struggling after childbirth” (FGD 1 & FGD 2).

Listening to information offered by health practitioners who regularly publish health content on social media is one of the most effective and efficient ways for fathers to prepare a safe birth for mothers.

“Several times, my wife and I have attended delivery preparation classes led by Instagram influencer midwives. From our perspective, these classes are highly effective and efficient as they greatly assist us in sorting through the misconceptions and facts circulating in society” (FGD 1).

“The explore feature on my personal Instagram now contains information about childbirth preparation, such as yoga classes and others; this makes me, as a husband, also have a sense of responsibility for the health of my wife and child” (FGD 3).

Postpartum support

Postpartum support is crucial, as many parents frequently overlook the postpartum phase, concentrating instead on the mother’s health throughout pregnancy and childbirth. Mothers must achieve psychological adaptation during this era to avert mental health disorders that could adversely affect both their own and their baby’s physical health. Therefore, the infant birth significantly highlights the need for postpartum support. Participants acquired competencies to flourish as fathers and husbands by overseeing mother and child health care throughout the crucial postpartum period.

“My biological mother and mother-in-law assert that fulfilling nutritional requirements post-delivery is paramount for ensuring adequate breast milk production and the child’s health. Consequently, I supply nutrients such as fruits, vegetables, meat, and vitamins to enhance breast milk production” (FGD 1).

This study highlights the significance of the father’s role as a breastfeeding supporter, consistently available to assist the mother during the initial phases of breastfeeding.

“The wife consistently awakens during the night to breastfeed the infant and to change the baby’s diaper. Even if I am drowsy, I must awaken and attend to my wife during her nursing. Despite this, I frequently fall asleep soundly” (FGD 2)

“I perform oxytocin and lactation massages on my wife. Despite the presence of numerous unsuitable massage techniques, my wife remains calm and comfortable, which, in turn, satisfies me. Occasionally, when my wife is exhausted, her breastfeeding posture is incorrect, prompting me to assist (FGD 2 and FGD 3).

The transformation in patriarchal culture appears evident among the FGD participants. They exhibited gender-responsive attitudes and attempted to engage in domestic household tasks during the early postpartum and nursing phases.

“I assist my wife in cleaning the bottles utilized for breast milk expression. Had I not recently become a father, I could have lacked knowledge regarding the cleaning and sterilizing breast milk bottles” (FGD 3).

“On multiple occasions, we refrained from using disposable diapers for our infant due to concerns regarding diaper rash, necessitating more frequent laundering of the cloth diapers. I assisted in washing them to prevent my wife from becoming fatigued” (FGD 3).

Discussion

This study illustrates fathers' opinions of participation in maternal and child health care during the perinatal period regarding financial support, facilitating a healthy pregnancy, preparing for safe delivery, and postpartum support. Most participants originated from financially stable families, all earning above the regional minimum wage. A study indicates that women from higher-income households experience more subjective well-being compared to those from lower-income families, particularly during pregnancy and childbirth. A further research study determined that enhanced husband involvement may yield more health benefits for pregnant women and children (Lewis et al., 2015). Participants in this study reported the importance of meeting the maternal primary needs, including comprehensive financial planning for the pregnancy, postpartum, and lactation phases. Despite participants earning above the minimum monthly salary, only 10% belong to upper-middle-class households; the rest are middle-class families with extensive knowledge of maternity and child health initiatives. Husbands, who also play the role of fathers, must fulfill the financial needs of their wives and children, making this aspect crucial. In Nepal, a developing nation similar to Indonesia, men perceived it as their duty to accompany their wives to health care facilities, provide support, and offer financial assistance (Lewis et al., 2015). This issue indicates that even if a spouse is not part of the upper middle class, meeting the family's financial obligations will contribute to familial well-being. An Iranian study reveals that certain participants hold the view that a partner needs to support his wife with perinatal care at home, as well as in the care of infants and older children and in addressing financial issues. This study continues that the husband should enhance his understanding and effectively utilize maternal and baby health information during the perinatal period. The related category comprised two subcategories, including informational and tangible support, the latter encompasses financial assistance (Mehran et al., 2020).

This study found that promoting a healthy pregnancy is a component of paternal involvement in mother health care during the perinatal period. The husband's involvement throughout pregnancy, including providing emotional support and empathy and addressing nutritional requirements, all help foster a successful pregnancy. This outcome is significant, particularly given that prior research has indicated a lack of the husband's participation in maternal healthcare. This results from sociocultural obstacles, such as a dominant patriarchal culture, insufficient information, and societal pressure (Firouzan et al., 2018, Firouzan et al., 2019; Mat Lowe, 2017; Nesane & Mulaudzi, 2024). The pervasive societal stigma associated with prenatal care makes it impossible for men to be involved as it relates to gender mainstreaming. Policymakers and scholars must acknowledge the substantial role of men in maternal health care during pregnancy (Shibeshi et al., 2023). Most participants in this study possessed higher education, with 8 obtaining master's degrees internationally. A study in Nepal revealed that male migration to urban regions and overseas resulted in a shift in patriarchal society, enhancing exposure to foreign ideas that transformed gender norms (Lewis et al., 2015).

This study involved individuals who acknowledged the significance of fathers' involvement in maternal and newborn health. These individuals are adept at using social media to access a wide range of reliable and accurate information related to mother and child health. They believe that social media is more productive and efficient for participants, allowing them to engage during work breaks easily. Contemporary social media technology has the potential to transform gender norms, emphasizing that paternal engagement is a crucial factor in promoting maternal and child health throughout the perinatal period (Chee et al., 2024; Saher et al., 2024).

Participants assert that husbands and fathers must empathize with mothers during pregnancy and breastfeeding. It has been shown that empathy extended towards spouses is intrinsically linked to efforts to comprehend them emotionally and cognitively during the perinatal period. Experts regard compassionate and sympathetic attention as the crucial component of partner involvement in perinatal care (Boorman et al., 2019; Firouzan et al., 2018; Firouzan et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2024). Empathy is the capacity to convey sensitive awareness and regard for others' emotions helpfully, fostering mutual trust, shared understanding, and the cultivation of essential attributes in any interaction (Moudatsou et al., 2020). Both men and women acknowledge their partners as the optimal sources of emotional support for their wives during the perinatal period (Sayakhot & Carolan-Olah, 2016). It is believed that emotional support from spouses is the primary determinant in alleviating postpartum depression (Ergo et al., 2011).

The subsequent finding in this study indicates that fathers who meet the mother's nutritional requirements during the perinatal period contribute to ensuring a healthy pregnancy and comprehensive postpartum support. Participants recognize that the obligation to provide nutrition for the family is no longer solely associated with maternal and domestic responsibilities, as males also play a crucial role in meeting the nutritional demands essential for the health of mothers and children. The fetal programming hypothesis, often known as DOHaD (developmental origins of health and disease), pertains to the correlation between maternal exposure to environmental stimuli and the emergence of complex disorders in adulthood. This concept posits that alterations during fetal development, such as nutritional deficits or environmental stressors, may predispose individuals to complex disorders in adulthood (Barouki et al., 2012; Hales & Barker, 2001). Maternal health and dietary composition throughout the perinatal period greatly influence the offspring's well-being. Epidemiological studies indicate that maternal diet and metabolic condition significantly influence the development of brain circuits that govern conduct, leading to enduring effects on child behavior. How maternal diet and metabolic profiles affect the perinatal environment are largely unclear; however, recent studies indicate that elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, nutrients (such as glucose and fatty acids), and hormones (including insulin and leptin) impact the environment of the developing offspring (Castillo et al., 2023; Sullivan et al., 2014). Growing research indicates that a father's dietary habits influence the emergence of disease in his children. Consequently, fathers and mothers each contribute to satisfying one another's dietary requirements within the family unit (Dimofski et al., 2021).

This study demonstrates that fathers' participation during the delivery is a component of ensuring a safe delivery. A content analysis study indicated that fathers felt empowered and desired to assume their part during the delivery of their child. Consequently, further measures are required to enhance paternal participation during antenatal clinic visits, labor, and postnatal care (Smith et al., 2024). The experience of fathers in the delivery room is significant. Their presence in the delivery room can have beneficial psychological and physiological effects for both the mother and the infant (Firouzan et al., 2018). Simultaneously, not all physicians and midwives desire the presence of fathers in the birth room. While some view fathers' involvement favorably, their presence can have adverse effects such as heightening maternal anxiety, prolonging labor, potentially leading to unnecessary surgical interventions, and increasing the risk of legal action in the event of complications (Firouzan et al., 2019). Midwives must also inform men about the progress of their wives' labor to ensure a positive and interactive birth experience for them. Considering the beneficial impact of fathers' presence in the delivery room, measures to enhance their accommodation during labor should be implemented (Ocho et al., 2018).

The study's final findings indicate that postpartum support contributed to dads' engagement in mother and child health care during the perinatal period. Fathers intentionally participate in several mother-child activities, such as fathers breastfeeding support, which ultimately transforms the previously established patriarchal culture surrounding them. A systematic evaluation indicated that including fathers in breastfeeding initiatives can enhance both the prevalence and duration of breastfeeding in infants (Koksal et al., 2022). Moreover, increasing evidence indicates the association between paternal participation and favorable child health outcomes (Yogman & Garfield, 2016). Father involvement in child care correlates with the onset and maintenance of breastfeeding (Abbass-Dick et al., 2015), reduced nocturnal awakenings among newborns, and enhanced mother sleep. Consequently, educational initiatives about breastfeeding and safe sleep have started incorporating fathers (Tikotzky et al., 2015).

This study had some limitations. In this study, only participants with adequate internet connectivity and a high level of education could participate online via the Zoom meeting platform. Consequently, the results do not reflect the experiences of all Indonesian fathers, and only participants who were well-educated and had the technological resources to access accurate information about maternal healthcare during the perinatal period demonstrate the transformation in patriarchal culture and father involvement during this period. This study did not explore the wives' views of these husbands and fathers. This study was conducted in the Indonesian cultural context, and its results can only be generalized to similar contexts.

Conclusion

This study found that financial support, ensuring a healthy pregnancy, preparing for safe delivery, and postpartum support are the Indonesian fathers’ perceptions of maternal health during perinatal care. In Indonesia, we acknowledge a shift in patriarchal society when fathers demonstrate a significant commitment to participating in maternal and newborn health care throughout the perinatal period. This shift may occur due to the willingness to assume the role of a father figure, thereby fostering a conducive environment for the well-being of mothers and children. This preparedness fosters cultural transformations, including demonstrating presence and empathy during pregnancy and labor, active involvement in domestic responsibilities, emotional support, fulfillment of nutritional requirements throughout pregnancy and the postpartum phase, and engagement with social media to enhance postpartum assistance as a father who supports breastfeeding. This study mainly included fathers with relatively stable financial circumstances (income exceeding the regional minimum wage) and high levels of education, rendering it less typical of the broader community of fathers in Indonesia as a developing nation. Indeed, there are disparities in the perspectives and attitudes of fathers who actively engage in maternal and newborn health care compared to those from less advantaged financial and educational backgrounds. Further research must encompass all fathers, regardless of educational attainment or economic status. It is also recommended that such a study be conducted with the participation of both husband and wife.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethical Research Committee of Universitas Respati Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia, accepted this research (Code: 190/SK.KEPK/UNR/V/2024). Participants provided written consent for the execution and documentation of the interviews; their involvement was voluntary, allowing them to withdraw from the study at their discretion; confidentiality regarding participants’ information, including names, phone numbers, and addresses, was assured.

Funding

This research was funded by Universitas Respati Yogyakarta, Jakarta, Indonesia, for the 2023/2024 fiscal year

Authors' contributions

Study design, investigation, analysis and writing: Giyawati Yulilania Okinarum; Data collection: Inayati Ceria; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Universitas Respati Yogyakarta for funding this research, as well as to the esteemed participants and collaborators, including Ruang Sehati, Rafflesia Selaras Yogyakarta Company, Gentle Touch with Love Company, Neloni Birth Center, and Abhirama Yoga Studio.

References

Abbass-Dick, J., et al., 2015. Coparenting breastfeeding support and exclusive breastfeeding: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics, 135(1), pp. 102–10. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2014-1416] [PMID]

Barouki, R.,et al., 2012. Developmental origins of non-communicable disease: Implications for research and public health. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 11, pp. 42. [DOI:10.1186/1476-069X-11-42] [PMID]

Boorman, R. J., et al., 2019. Empathy in pregnant women and new mothers: A systematic literature review. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 37(1), pp. 84–103. [DOI:10.1080/02646838.2018.1525695] [PMID]

Castillo, P., et al., 2023. Influence of maternal metabolic status and diet during the perinatal period on the metabolic programming by leptin ingested during the suckling period in rats. Nutrients, 15(3), pp. 570. [DOI:10.3390/nu15030570] [PMID]

Chee, R. M., Capper, T. S. & Muurlink, O. T., 2024. Social media influencers’ impact during pregnancy and parenting: A qualitative descriptive study. Research in Nursing & Health, 47(1), pp. 7–16. [DOI:10.1002/nur.22350] [PMID]

Creswell, J. W. & Poth, C. N., 2017. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. California: SAGE Publication, Inc. [Link]

Davis, J., Luchters, S. & Holmes, W., 2012. Men and maternal and newborn health: Benefits, harms, challenges and potential strategies for engaging men, Compass: Women’s and Children’s Health Knowledge Hub. Melbourne, Australia: Burnet Institute; 2012. [Link]

Dimofski, P., et al., 2021. Consequences of paternal nutrition on offspring health and disease. Nutrients, 13(8), pp. 2818. [DOI: 10.3390/nu13082818] [PMID]

Ergo, A., et al., 2011. Strengthening health systems to improve maternal, Neonatal and child health outcomes: A framework. Washington, D.C: USAID. [Link]

Firouzan, V., et al., 2019. Barriers to men’s participation in perinatal care: A qualitative study in Iran. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), pp. 45. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-019-2201-2] [PMID]

Firouzan, V., et al., 2018. Participation of father in perinatal care: A qualitative study from the perspective of mothers, fathers, caregivers, managers and policymakers in Iran. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), pp. 297. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-018-1928-5] [PMID]

Forbes, F., et al., 2021. Fathers’ involvement in perinatal healthcare in Australia: Experiences and reflections of Ethiopian-Australian men and women. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), pp. 1029. [DOI:10.1186/s12913-021-07058-z] [PMID]

Gopal, P., et al., 2020. Male involvement in reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: Evaluating gaps between policy and practice in Uganda. Reproductive Health, 17(1), pp. 114. [DOI:10.1186/s12978-020-00961-4] [PMID]

Graneheim, U. H. & Lundman, B., 2004. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), pp. 105–12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

Hales, C. N. & Barker, D. J., 2001. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. British Medical Bulletin, 60, pp. 5–20. [DOI:10.1093/bmb/60.1.5] [PMID]

Hennink, M. & Kaiser, B. N., 2022. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 292, pp. 114523. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523] [PMID]

King, J. C., 2013. Strategies to reduce maternal mortality in developed countries. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 25(2), pp. 117–23. [DOI:10.1097/GCO.0b013e32835e1505] [PMID]

Koksal, I., Acikgoz, A. & Cakirli, M., 2022. The effect of a father’s support on breastfeeding: A systematic review. Breastfeeding Medicine: The Official Journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, 17(9), pp. 711–22. [DOI:10.1089/bfm.2022.0058] [PMID]

Kortsmit, K., et al., 2020. Paternal Involvement and Maternal Perinatal Behaviors: Pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2012-2015. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974), 135(2), pp. 253–61. [DOI:10.1177/0033354920904066] [PMID]

Lewis, S., Lee, A. & Simkhada, P., 2015. The role of husbands in maternal health and safe childbirth in rural Nepal: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15, pp. 162. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-015-0599-8] [PMID]

Lincoln, Y. S., Guba, E. G. & Pilotta, J. J., 1985. Naturalistic inquiry: Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1985, 416 pp., $25.00 (Cloth).International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 9(4), pp. 438-9. [DOI:10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8]

Lowe, M., 2017. Social and cultural barriers to husbands’ involvement in maternal health in rural Gambia. The Pan African Medical Journal, 27, pp. 255. [DOI:10.11604/pamj.2017.27.255.11378] [PMID]

Mehran, N., et al., 2020. Spouse’s participation in perinatal care: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), pp. 489. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-03111-7] [PMID]

Moudatsou, M., et al., 2020. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare (Basel), 8(1), pp. 26. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare8010026] [PMID]

Nesane, K. V. & Mulaudzi, F. M., 2024. Cultural barriers to male partners’ involvement in antenatal care in Limpopo province. Health SA, 29, pp. 2322. [DOI:10.4102/hsag.v29i0.2322] [PMID]

Ocho, O. N., Moorley, C. & Lootawan, K. A., 2018. Fathers’ presence in the birth room - implications for professional practice in the Caribbean. Contemporary Nurse, 54(6), pp. 617–29. [DOI:10.1080/10376178.2018.1552524] [PMID]

Saher, A., et al., 2024. Fathers’ use of social media for social comparison is associated with their food parenting practices. Appetite, 194, pp. 107201. [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2024.107201] [PMID]

Sayakhot, P. & Carolan-Olah, M., 2016. Internet use by pregnant women seeking pregnancy-related information: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16, pp. 65. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-016-0856-5] [PMID]

Schwandt, T. A., Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G., 2007. Judging interpretations: But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 2007(114), pp. 11-25. [DOI:10.1002/ev.223]

Shibeshi, K., et al., 2023. Understanding gender-based perception during pregnancy: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Women's Health, 15, pp. 1523–35. [DOI:10.2147/IJWH.S418653] [PMID]

Singh, D., Lample, M. & Earnest, J., 2014. The involvement of men in maternal health care: Cross-sectional, pilot case studies from Maligita and Kibibi, Uganda. Reproductive Health, 11, pp. 68. [DOI:10.1186/1742-4755-11-68] [PMID]

Smith, C., Pitter, C. & Udoudo, D. A., 2024. Fathers’ experiences during delivery of their newborns: A content analysis. International Journal of Community Based Nursing & Midwifery, 12(1), pp. 23-31. [DOI:10.30476/IJCBNM.2023.100009.2337]

Sullivan, E. L., Nousen, E. K. & Chamlou, K. A., 2014. Maternal high fat diet consumption during the perinatal period programs offspring behavior. Physiology & Behavior, 123, pp. 236–42. [DOI:10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.07.014] [PMID]

Tikotzky, L., et al., 2015. Infant sleep development from 3 to 6 months postpartum: Links with maternal sleep and paternal involvement. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 80(1), pp. 107–24. [DOI:10.1111/mono.12147] [PMID]

Tohotoa, J., et al., 2011. Supporting mothers to breastfeed: the development and process evaluation of a father inclusive perinatal education support program in Perth, Western Australia. Health Promotion International, 26(3), pp. 351-61. [DOI:10.1093/heapro/daq077] [PMID]

WHO., 2016. Maternal mortality. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data. Geneva: WHO. [Link]

WHO., 2016. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. Geneva: WHO. [Link]

Yogman, M., Garfield, C. F. & Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child And Family Health., 2016. Fathers’ roles in the care and development of their children: The role of pediatricians. Pediatrics, 138(1), pp. e20161128. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2016-1128] [PMID]

Zhu, Y., et al., 2024. Implications of perceived empathy from spouses during pregnancy for health-related quality of life among pregnant women: A cross-sectional study in Anhui, China. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 24(1), pp. 269. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-024-06419-w] [PMID]

The perinatal phase, encompassing pregnancy through postpartum, is a critical, demanding, and distinctive period in a woman’s life. The mental and physical well-being of women significantly influences fetal health, successful vaginal delivery, and nursing (Firouzan et al., 2018, Firouzan et al., 2019). The International Conference on Population and Development and the Fourth World Conference on Women emphasized the advantage of the father’s role in reproductive health and women’s rights (Singh et al., 2014), while Lewis et al. (2015) championed this as a human rights imperative. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that a mother dies every 2 minutes due to complications related to pregnancy and delivery (WHO, 2016b; WHO, 2016a); nevertheless, 99% of these fatalities are preventable (King, 2013). The WHO characterizes fathers’ involvement in the safe motherhood program as enhancing access to perinatal care, promoting awareness, and engaging in childbirth preparation initiatives. Mothers who get spousal support throughout pregnancy experience enhanced empowerment in managing stress and challenges, demonstrate improved tolerance during childbirth, and adapt more readily to their children postnatally (Kortsmit et al., 2020; Tohotoa et al., 2011).

Australia, a prosperous nation, conducted a study that found a significant correlation between paternal engagement in middle- and low-income countries and maternal mortality after childbirth (Davis et al., 2012). Moreover, supplementary research indicates that paternal involvement positively influences the reduction of smoking and alcohol consumption, the risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, intrauterine growth restriction, and infant mortality (Forbes et al., 2021). The willingness of fathers to contribute to maternal health has increased in recent years. Yet, few countries have enacted legislation acknowledging fathers’ contributions to maternal, infant, and child health. Research demonstrates that, despite such policies, implementation is deficient in these domains since men are frequently marginalized from formulating and administering participation initiatives in maternal health (Gopal et al., 2020).

In Indonesia, a developing nation characterized by a robust patriarchal culture, the involvement of fathers during the perinatal period is atypical. There is a favorable perception of enhanced paternal participation in women’s health and social welfare throughout the perinatal period. Nonetheless, when examining the perspectives of individuals and recipient groups regarding gender roles across various cultures, it is imperative to acknowledge their delicate nature. Qualitative research identifies, describes, and conceptualizes participant experiences, thus enhancing comprehension and knowledge of fathers’ roles in supporting women during pregnancy and the postnatal period. Researchers frequently employ this method to elucidate concepts and their interrelations (Creswell & Poth, 2017). This qualitative study sought to explore fathers’ perspectives and experiences regarding maternal health care throughout the perinatal period in Indonesia. We conducted this study on a national scale to optimize benefits for end users, specifically by establishing a framework for enhancing maternal strength during the perinatal period. The study team consists of midwives specializing in community midwifery, which is closely associated with empowering parents to improve perinatal health.

Materials and Methods

Design, setting, and participants

This study employed a qualitative research method, including a descriptive qualitative design and a content analysis approach. The participants included 30 fathers from 8 Indonesian provinces: South Sumatra, DKI Jakarta, West Java, DI Yogyakarta, East Java, East Kalimantan, Bali, and West Nusa Tenggara. We distributed the call to participants online via social media. Fathers whose wives are in the perinatal phase, fathers who are physically and emotionally healthy, eager to participate in the study process from start to finish, have reliable internet access, and might operate Zoom meetings are all eligible.

Data collection

Three focus group discussions (FGDs) (each with 10 participants) were conducted online using the Zoom meeting platform. The study data were collected from May to June 2024. Each session lasted approximately 60 minutes. It began with an open question: “How can fathers participate in caring for their wives during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum?” “Please explain!” As the FGD advanced, the author generated more specific inquiries based on the interview framework, such as “do you feel at ease participating in maternal healthcare during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period?” and “Are there any barriers that inhibit your involvement in maternal health care? Participants’ comments and discussions raised further questions and guided the interviews. The researcher and a midwife specializing in qualitative research continued facilitating the FGDs by employing probing questions to achieve the research objectives. All participants showed similar responses and patterns across the 3 focus group sessions, and concurrent data analysis did not result in new categories that would indicate data saturation. In addition, the study utilized a homogeneous group with well-defined objectives, contributing to data saturation (Hennink & Kaiser, 2022).

Data analysis

We evaluated the data using conventional content analysis and NVivo software, version 14 to manage the data. The interviews were conducted in Indonesian, recorded using Zoom Meeting technology, and saved in the cloud. The materials were reread many times to ensure a thorough grasp of the content. The author conducted data analysis simultaneously with the FGDs, following the established methodology of Graneheim and Lundman (2004). TheFGDs were transcribed verbatim and were reviewed multiple times to derive primary codes. The analogous primary codes were combined to form broader categories based on their similarities and differences, ultimately extracting latent concepts from the data (Schwandt et al., 2007).

Rigor and trustworthiness

This study employed references from Lincoln and Guba (1985) to demonstrate the data’s credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. To enhance credibility, the participants were drawn from 8 provinces in Indonesia, spanning both western and central Indonesian time. This criterion led to varying interview times due to a one-hour time difference between researchers in central and west Indonesia. Prolonged engagement with participants facilitated trust and produced more comprehensive data. After establishing the categories, the researcher employed member checks. We recalibrated and amended any categories and subcategories that conflicted with the participants’ perspectives. We endeavored to thoroughly elucidate the research context and participants’ perspectives regarding transferability. To ensure dependability, four specialists in qualitative research (a midwife, a nutritionist, an academician, and a gender-responsive expert) evaluated and verified the research methodology and data analysis to confirm that the results were consistent and replicable. An independent reviewer validated the research methodology and data interpretation to ensure confirmability.

Results

Participants’ profile

This study included 30 father participants, primarily aged 25-35, from 8 provinces in Indonesia. Each participant had one or more children and earned a salary above the minimum, as detailed in Table 1.

Four main themes emerged from the data, indicating how fathers are involved in maternal and child health care during the perinatal period in Indonesia: Financial support, ensuring a healthy pregnancy, preparing for a safe birth, and postpartum support (Table 2).

Financial support

The first theme indicates that paternal engagement in addressing financial support is crucial for maternal and child health care, as it necessitates fathers to comprehend and meet the mother’s and child’s essential requirements, such as clothes and nutrition. During the FGDs, the participants indicated that support in meeting the maternal primary needs demonstrates their preparedness as fathers:

“As a spouse and parent, I have the responsibility of sustaining the family’s financial well-being. As fathers and husbands, we must prepare ourselves” (FGD 1).

“Monthly pregnancy check-ups are quite costly. Nonetheless, the paramount concern is the health of my wife and child; so, with divine providence, a solution may emerge” (FGD 1).

“My financial circumstances are below average, and I am confident that the men here possess varying financial capacities. It is our duty as men to provide for our wives and children. The capacity to honor agreements influences a man’s self-worth” (FGD 3).

Ideally, fathers should assume responsibility for meeting fundamental maternal requirements, including the provision of clothing and food. Financial considerations significantly influence the enhancement of prenatal and postnatal services, as articulated by participants in the FGD. Meeting dietary needs during pregnancy is crucial for women and their children’s health. Interventions for fathers, such as supplying fruit, vegetables, and meat, are the most effective steps made for mothers throughout pregnancy.

“I keep stocks of fruit, vegetables, meat, and nutritious food in the refrigerator.”

“Usually, at every pregnancy check-up, there are supplements and vitamins prescribed by a midwife or doctor, so I provide them.”

“Currently, I am responsible for the financial expenses associated with purchasing maternity attire, complete outfits, and necessary equipment for childbirth while my wife makes the purchases. I also incur the expense of prenatal vitamins and endeavor to meet my wife’s nutritional needs by supplying balanced, nutritious cuisine” (FGD 2).

Ensuring a healthy pregnancy

The father’s involvement and presence during pregnancy are crucial in promoting maternal health. Participants in the FGD indicated that the husband’s presence during prenatal check-ups is crucial for providing the mother with support and attention. Pregnant women require financial assistance and spousal support during prenatal examinations and fitness activities, such as couples’ prenatal yoga, creating comfort and security.

“I consistently accompany my wife to her prenatal check-ups and enter the examination room at the polyclinic to ascertain the health of both my wife and the fetus. I often accompany my wife to prenatal yoga sessions. (FGD 1, FGD 2, and FGD 3).

Fathers assume partnership roles with pregnant women in their households, necessitating the involvement of both sides. The active participation of dads in household tasks, such as dishwashing and cleaning, disrupts the cycle of patriarchy. The psychological interaction will positively influence the health of pregnant women.

“In the first trimester, my wife experienced terrible diarrhea; I found it distressing to witness her condition, and the doctor indicated a risk of miscarriage, prompting me to advise her to rest and refrain from household chores. On multiple occasions, I assumed responsibility for or employed a housemaid” (FGD 3).

A father’s commendation of a mother during gestation exemplifies the essential emotional support required. A father’s vocal engagement immediately enhances the mother’s happiness, boosting her psychological adaptability during pregnancy.

“I once participated in a prenatal yoga class with a couple, where the instructing midwife highlighted the significance of attention and commendation for pregnant women, as it can enhance their mood” (FGD 1).

The woman endured back and waist pain during her pregnancy as a result of physiological adaptation. The father’s gentle massage demonstrated a necessity for empathy.

“I provided my wife with a soothing massage during her pregnancy. Nevertheless, for specialized care, I typically engage a pregnant massage therapist” (FGD 1 & FGD 2).

“My wife expressed difficulty in trimming her nails due to her large abdomen and swollen feet, prompting me to assist her” (FGD 3).

Utilizing social media proficiently can assist fathers in enhancing their analytical and critical thinking abilities, thereby ensuring a secure pregnancy for their spouses.

“I monitor social media for the latest updates about my wife’s pregnancy. I also endeavor to exclude invalid material. Presently, information from physicians and midwives actively creating social media content is beneficial. This could potentially help us, as non-experts, better understand the misconceptions and reality surrounding pregnancy” (FGD 1 & FGD 2).

“I accompany my wife to online pregnancy classes sourced from social media to obtain accurate information” (FGD 3).

Preparing for a safe delivery

Participants in the FGDs asserted that guaranteeing a safe delivery is their obligation. This factor signifies their preparedness to receive the arrival of their baby. The father’s presence and empathy during birth are vital to the mother and child’s health.

“From the beginning, I played a role in finding the best place to give birth, of course for the health and safety of my wife and child” (FGD 1).

“ I received full assistance from my workplace throughout the delivery. Fortunately, I was able to take leave” (FGD 2).

“The key is to make my wife happy, so I keep praising her, ‘good honey, you’re good at pushing honey,’ stroking her back and waist. I kiss her forehead and chant prayers in her ear; that way, my wife is enthusiastic” (FGD 3).

“From the start, I left everything to my wife; of course, she knows what is best, and I completely support her decision to give birth. The most essential thing to me is the safety of my wife and child. I completely support newborns that breastfeed themselves (read: Early breastfeeding initiation), and my responsibility is always to be there to accompany my wife, who is struggling after childbirth” (FGD 1 & FGD 2).

Listening to information offered by health practitioners who regularly publish health content on social media is one of the most effective and efficient ways for fathers to prepare a safe birth for mothers.

“Several times, my wife and I have attended delivery preparation classes led by Instagram influencer midwives. From our perspective, these classes are highly effective and efficient as they greatly assist us in sorting through the misconceptions and facts circulating in society” (FGD 1).

“The explore feature on my personal Instagram now contains information about childbirth preparation, such as yoga classes and others; this makes me, as a husband, also have a sense of responsibility for the health of my wife and child” (FGD 3).

Postpartum support

Postpartum support is crucial, as many parents frequently overlook the postpartum phase, concentrating instead on the mother’s health throughout pregnancy and childbirth. Mothers must achieve psychological adaptation during this era to avert mental health disorders that could adversely affect both their own and their baby’s physical health. Therefore, the infant birth significantly highlights the need for postpartum support. Participants acquired competencies to flourish as fathers and husbands by overseeing mother and child health care throughout the crucial postpartum period.

“My biological mother and mother-in-law assert that fulfilling nutritional requirements post-delivery is paramount for ensuring adequate breast milk production and the child’s health. Consequently, I supply nutrients such as fruits, vegetables, meat, and vitamins to enhance breast milk production” (FGD 1).

This study highlights the significance of the father’s role as a breastfeeding supporter, consistently available to assist the mother during the initial phases of breastfeeding.

“The wife consistently awakens during the night to breastfeed the infant and to change the baby’s diaper. Even if I am drowsy, I must awaken and attend to my wife during her nursing. Despite this, I frequently fall asleep soundly” (FGD 2)

“I perform oxytocin and lactation massages on my wife. Despite the presence of numerous unsuitable massage techniques, my wife remains calm and comfortable, which, in turn, satisfies me. Occasionally, when my wife is exhausted, her breastfeeding posture is incorrect, prompting me to assist (FGD 2 and FGD 3).

The transformation in patriarchal culture appears evident among the FGD participants. They exhibited gender-responsive attitudes and attempted to engage in domestic household tasks during the early postpartum and nursing phases.

“I assist my wife in cleaning the bottles utilized for breast milk expression. Had I not recently become a father, I could have lacked knowledge regarding the cleaning and sterilizing breast milk bottles” (FGD 3).

“On multiple occasions, we refrained from using disposable diapers for our infant due to concerns regarding diaper rash, necessitating more frequent laundering of the cloth diapers. I assisted in washing them to prevent my wife from becoming fatigued” (FGD 3).

Discussion

This study illustrates fathers' opinions of participation in maternal and child health care during the perinatal period regarding financial support, facilitating a healthy pregnancy, preparing for safe delivery, and postpartum support. Most participants originated from financially stable families, all earning above the regional minimum wage. A study indicates that women from higher-income households experience more subjective well-being compared to those from lower-income families, particularly during pregnancy and childbirth. A further research study determined that enhanced husband involvement may yield more health benefits for pregnant women and children (Lewis et al., 2015). Participants in this study reported the importance of meeting the maternal primary needs, including comprehensive financial planning for the pregnancy, postpartum, and lactation phases. Despite participants earning above the minimum monthly salary, only 10% belong to upper-middle-class households; the rest are middle-class families with extensive knowledge of maternity and child health initiatives. Husbands, who also play the role of fathers, must fulfill the financial needs of their wives and children, making this aspect crucial. In Nepal, a developing nation similar to Indonesia, men perceived it as their duty to accompany their wives to health care facilities, provide support, and offer financial assistance (Lewis et al., 2015). This issue indicates that even if a spouse is not part of the upper middle class, meeting the family's financial obligations will contribute to familial well-being. An Iranian study reveals that certain participants hold the view that a partner needs to support his wife with perinatal care at home, as well as in the care of infants and older children and in addressing financial issues. This study continues that the husband should enhance his understanding and effectively utilize maternal and baby health information during the perinatal period. The related category comprised two subcategories, including informational and tangible support, the latter encompasses financial assistance (Mehran et al., 2020).

This study found that promoting a healthy pregnancy is a component of paternal involvement in mother health care during the perinatal period. The husband's involvement throughout pregnancy, including providing emotional support and empathy and addressing nutritional requirements, all help foster a successful pregnancy. This outcome is significant, particularly given that prior research has indicated a lack of the husband's participation in maternal healthcare. This results from sociocultural obstacles, such as a dominant patriarchal culture, insufficient information, and societal pressure (Firouzan et al., 2018, Firouzan et al., 2019; Mat Lowe, 2017; Nesane & Mulaudzi, 2024). The pervasive societal stigma associated with prenatal care makes it impossible for men to be involved as it relates to gender mainstreaming. Policymakers and scholars must acknowledge the substantial role of men in maternal health care during pregnancy (Shibeshi et al., 2023). Most participants in this study possessed higher education, with 8 obtaining master's degrees internationally. A study in Nepal revealed that male migration to urban regions and overseas resulted in a shift in patriarchal society, enhancing exposure to foreign ideas that transformed gender norms (Lewis et al., 2015).

This study involved individuals who acknowledged the significance of fathers' involvement in maternal and newborn health. These individuals are adept at using social media to access a wide range of reliable and accurate information related to mother and child health. They believe that social media is more productive and efficient for participants, allowing them to engage during work breaks easily. Contemporary social media technology has the potential to transform gender norms, emphasizing that paternal engagement is a crucial factor in promoting maternal and child health throughout the perinatal period (Chee et al., 2024; Saher et al., 2024).

Participants assert that husbands and fathers must empathize with mothers during pregnancy and breastfeeding. It has been shown that empathy extended towards spouses is intrinsically linked to efforts to comprehend them emotionally and cognitively during the perinatal period. Experts regard compassionate and sympathetic attention as the crucial component of partner involvement in perinatal care (Boorman et al., 2019; Firouzan et al., 2018; Firouzan et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2024). Empathy is the capacity to convey sensitive awareness and regard for others' emotions helpfully, fostering mutual trust, shared understanding, and the cultivation of essential attributes in any interaction (Moudatsou et al., 2020). Both men and women acknowledge their partners as the optimal sources of emotional support for their wives during the perinatal period (Sayakhot & Carolan-Olah, 2016). It is believed that emotional support from spouses is the primary determinant in alleviating postpartum depression (Ergo et al., 2011).

The subsequent finding in this study indicates that fathers who meet the mother's nutritional requirements during the perinatal period contribute to ensuring a healthy pregnancy and comprehensive postpartum support. Participants recognize that the obligation to provide nutrition for the family is no longer solely associated with maternal and domestic responsibilities, as males also play a crucial role in meeting the nutritional demands essential for the health of mothers and children. The fetal programming hypothesis, often known as DOHaD (developmental origins of health and disease), pertains to the correlation between maternal exposure to environmental stimuli and the emergence of complex disorders in adulthood. This concept posits that alterations during fetal development, such as nutritional deficits or environmental stressors, may predispose individuals to complex disorders in adulthood (Barouki et al., 2012; Hales & Barker, 2001). Maternal health and dietary composition throughout the perinatal period greatly influence the offspring's well-being. Epidemiological studies indicate that maternal diet and metabolic condition significantly influence the development of brain circuits that govern conduct, leading to enduring effects on child behavior. How maternal diet and metabolic profiles affect the perinatal environment are largely unclear; however, recent studies indicate that elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, nutrients (such as glucose and fatty acids), and hormones (including insulin and leptin) impact the environment of the developing offspring (Castillo et al., 2023; Sullivan et al., 2014). Growing research indicates that a father's dietary habits influence the emergence of disease in his children. Consequently, fathers and mothers each contribute to satisfying one another's dietary requirements within the family unit (Dimofski et al., 2021).

This study demonstrates that fathers' participation during the delivery is a component of ensuring a safe delivery. A content analysis study indicated that fathers felt empowered and desired to assume their part during the delivery of their child. Consequently, further measures are required to enhance paternal participation during antenatal clinic visits, labor, and postnatal care (Smith et al., 2024). The experience of fathers in the delivery room is significant. Their presence in the delivery room can have beneficial psychological and physiological effects for both the mother and the infant (Firouzan et al., 2018). Simultaneously, not all physicians and midwives desire the presence of fathers in the birth room. While some view fathers' involvement favorably, their presence can have adverse effects such as heightening maternal anxiety, prolonging labor, potentially leading to unnecessary surgical interventions, and increasing the risk of legal action in the event of complications (Firouzan et al., 2019). Midwives must also inform men about the progress of their wives' labor to ensure a positive and interactive birth experience for them. Considering the beneficial impact of fathers' presence in the delivery room, measures to enhance their accommodation during labor should be implemented (Ocho et al., 2018).

The study's final findings indicate that postpartum support contributed to dads' engagement in mother and child health care during the perinatal period. Fathers intentionally participate in several mother-child activities, such as fathers breastfeeding support, which ultimately transforms the previously established patriarchal culture surrounding them. A systematic evaluation indicated that including fathers in breastfeeding initiatives can enhance both the prevalence and duration of breastfeeding in infants (Koksal et al., 2022). Moreover, increasing evidence indicates the association between paternal participation and favorable child health outcomes (Yogman & Garfield, 2016). Father involvement in child care correlates with the onset and maintenance of breastfeeding (Abbass-Dick et al., 2015), reduced nocturnal awakenings among newborns, and enhanced mother sleep. Consequently, educational initiatives about breastfeeding and safe sleep have started incorporating fathers (Tikotzky et al., 2015).

This study had some limitations. In this study, only participants with adequate internet connectivity and a high level of education could participate online via the Zoom meeting platform. Consequently, the results do not reflect the experiences of all Indonesian fathers, and only participants who were well-educated and had the technological resources to access accurate information about maternal healthcare during the perinatal period demonstrate the transformation in patriarchal culture and father involvement during this period. This study did not explore the wives' views of these husbands and fathers. This study was conducted in the Indonesian cultural context, and its results can only be generalized to similar contexts.

Conclusion

This study found that financial support, ensuring a healthy pregnancy, preparing for safe delivery, and postpartum support are the Indonesian fathers’ perceptions of maternal health during perinatal care. In Indonesia, we acknowledge a shift in patriarchal society when fathers demonstrate a significant commitment to participating in maternal and newborn health care throughout the perinatal period. This shift may occur due to the willingness to assume the role of a father figure, thereby fostering a conducive environment for the well-being of mothers and children. This preparedness fosters cultural transformations, including demonstrating presence and empathy during pregnancy and labor, active involvement in domestic responsibilities, emotional support, fulfillment of nutritional requirements throughout pregnancy and the postpartum phase, and engagement with social media to enhance postpartum assistance as a father who supports breastfeeding. This study mainly included fathers with relatively stable financial circumstances (income exceeding the regional minimum wage) and high levels of education, rendering it less typical of the broader community of fathers in Indonesia as a developing nation. Indeed, there are disparities in the perspectives and attitudes of fathers who actively engage in maternal and newborn health care compared to those from less advantaged financial and educational backgrounds. Further research must encompass all fathers, regardless of educational attainment or economic status. It is also recommended that such a study be conducted with the participation of both husband and wife.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethical Research Committee of Universitas Respati Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia, accepted this research (Code: 190/SK.KEPK/UNR/V/2024). Participants provided written consent for the execution and documentation of the interviews; their involvement was voluntary, allowing them to withdraw from the study at their discretion; confidentiality regarding participants’ information, including names, phone numbers, and addresses, was assured.

Funding

This research was funded by Universitas Respati Yogyakarta, Jakarta, Indonesia, for the 2023/2024 fiscal year

Authors' contributions

Study design, investigation, analysis and writing: Giyawati Yulilania Okinarum; Data collection: Inayati Ceria; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Universitas Respati Yogyakarta for funding this research, as well as to the esteemed participants and collaborators, including Ruang Sehati, Rafflesia Selaras Yogyakarta Company, Gentle Touch with Love Company, Neloni Birth Center, and Abhirama Yoga Studio.

References

Abbass-Dick, J., et al., 2015. Coparenting breastfeeding support and exclusive breastfeeding: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics, 135(1), pp. 102–10. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2014-1416] [PMID]

Barouki, R.,et al., 2012. Developmental origins of non-communicable disease: Implications for research and public health. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 11, pp. 42. [DOI:10.1186/1476-069X-11-42] [PMID]

Boorman, R. J., et al., 2019. Empathy in pregnant women and new mothers: A systematic literature review. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 37(1), pp. 84–103. [DOI:10.1080/02646838.2018.1525695] [PMID]

Castillo, P., et al., 2023. Influence of maternal metabolic status and diet during the perinatal period on the metabolic programming by leptin ingested during the suckling period in rats. Nutrients, 15(3), pp. 570. [DOI:10.3390/nu15030570] [PMID]

Chee, R. M., Capper, T. S. & Muurlink, O. T., 2024. Social media influencers’ impact during pregnancy and parenting: A qualitative descriptive study. Research in Nursing & Health, 47(1), pp. 7–16. [DOI:10.1002/nur.22350] [PMID]

Creswell, J. W. & Poth, C. N., 2017. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. California: SAGE Publication, Inc. [Link]

Davis, J., Luchters, S. & Holmes, W., 2012. Men and maternal and newborn health: Benefits, harms, challenges and potential strategies for engaging men, Compass: Women’s and Children’s Health Knowledge Hub. Melbourne, Australia: Burnet Institute; 2012. [Link]

Dimofski, P., et al., 2021. Consequences of paternal nutrition on offspring health and disease. Nutrients, 13(8), pp. 2818. [DOI: 10.3390/nu13082818] [PMID]

Ergo, A., et al., 2011. Strengthening health systems to improve maternal, Neonatal and child health outcomes: A framework. Washington, D.C: USAID. [Link]

Firouzan, V., et al., 2019. Barriers to men’s participation in perinatal care: A qualitative study in Iran. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), pp. 45. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-019-2201-2] [PMID]

Firouzan, V., et al., 2018. Participation of father in perinatal care: A qualitative study from the perspective of mothers, fathers, caregivers, managers and policymakers in Iran. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), pp. 297. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-018-1928-5] [PMID]

Forbes, F., et al., 2021. Fathers’ involvement in perinatal healthcare in Australia: Experiences and reflections of Ethiopian-Australian men and women. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), pp. 1029. [DOI:10.1186/s12913-021-07058-z] [PMID]

Gopal, P., et al., 2020. Male involvement in reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: Evaluating gaps between policy and practice in Uganda. Reproductive Health, 17(1), pp. 114. [DOI:10.1186/s12978-020-00961-4] [PMID]

Graneheim, U. H. & Lundman, B., 2004. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), pp. 105–12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

Hales, C. N. & Barker, D. J., 2001. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. British Medical Bulletin, 60, pp. 5–20. [DOI:10.1093/bmb/60.1.5] [PMID]

Hennink, M. & Kaiser, B. N., 2022. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 292, pp. 114523. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523] [PMID]

King, J. C., 2013. Strategies to reduce maternal mortality in developed countries. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 25(2), pp. 117–23. [DOI:10.1097/GCO.0b013e32835e1505] [PMID]

Koksal, I., Acikgoz, A. & Cakirli, M., 2022. The effect of a father’s support on breastfeeding: A systematic review. Breastfeeding Medicine: The Official Journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, 17(9), pp. 711–22. [DOI:10.1089/bfm.2022.0058] [PMID]

Kortsmit, K., et al., 2020. Paternal Involvement and Maternal Perinatal Behaviors: Pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2012-2015. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974), 135(2), pp. 253–61. [DOI:10.1177/0033354920904066] [PMID]

Lewis, S., Lee, A. & Simkhada, P., 2015. The role of husbands in maternal health and safe childbirth in rural Nepal: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15, pp. 162. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-015-0599-8] [PMID]

Lincoln, Y. S., Guba, E. G. & Pilotta, J. J., 1985. Naturalistic inquiry: Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1985, 416 pp., $25.00 (Cloth).International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 9(4), pp. 438-9. [DOI:10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8]

Lowe, M., 2017. Social and cultural barriers to husbands’ involvement in maternal health in rural Gambia. The Pan African Medical Journal, 27, pp. 255. [DOI:10.11604/pamj.2017.27.255.11378] [PMID]

Mehran, N., et al., 2020. Spouse’s participation in perinatal care: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), pp. 489. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-020-03111-7] [PMID]

Moudatsou, M., et al., 2020. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare (Basel), 8(1), pp. 26. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare8010026] [PMID]

Nesane, K. V. & Mulaudzi, F. M., 2024. Cultural barriers to male partners’ involvement in antenatal care in Limpopo province. Health SA, 29, pp. 2322. [DOI:10.4102/hsag.v29i0.2322] [PMID]

Ocho, O. N., Moorley, C. & Lootawan, K. A., 2018. Fathers’ presence in the birth room - implications for professional practice in the Caribbean. Contemporary Nurse, 54(6), pp. 617–29. [DOI:10.1080/10376178.2018.1552524] [PMID]

Saher, A., et al., 2024. Fathers’ use of social media for social comparison is associated with their food parenting practices. Appetite, 194, pp. 107201. [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2024.107201] [PMID]

Sayakhot, P. & Carolan-Olah, M., 2016. Internet use by pregnant women seeking pregnancy-related information: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16, pp. 65. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-016-0856-5] [PMID]

Schwandt, T. A., Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G., 2007. Judging interpretations: But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 2007(114), pp. 11-25. [DOI:10.1002/ev.223]

Shibeshi, K., et al., 2023. Understanding gender-based perception during pregnancy: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Women's Health, 15, pp. 1523–35. [DOI:10.2147/IJWH.S418653] [PMID]

Singh, D., Lample, M. & Earnest, J., 2014. The involvement of men in maternal health care: Cross-sectional, pilot case studies from Maligita and Kibibi, Uganda. Reproductive Health, 11, pp. 68. [DOI:10.1186/1742-4755-11-68] [PMID]

Smith, C., Pitter, C. & Udoudo, D. A., 2024. Fathers’ experiences during delivery of their newborns: A content analysis. International Journal of Community Based Nursing & Midwifery, 12(1), pp. 23-31. [DOI:10.30476/IJCBNM.2023.100009.2337]

Sullivan, E. L., Nousen, E. K. & Chamlou, K. A., 2014. Maternal high fat diet consumption during the perinatal period programs offspring behavior. Physiology & Behavior, 123, pp. 236–42. [DOI:10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.07.014] [PMID]

Tikotzky, L., et al., 2015. Infant sleep development from 3 to 6 months postpartum: Links with maternal sleep and paternal involvement. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 80(1), pp. 107–24. [DOI:10.1111/mono.12147] [PMID]

Tohotoa, J., et al., 2011. Supporting mothers to breastfeed: the development and process evaluation of a father inclusive perinatal education support program in Perth, Western Australia. Health Promotion International, 26(3), pp. 351-61. [DOI:10.1093/heapro/daq077] [PMID]

WHO., 2016. Maternal mortality. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data. Geneva: WHO. [Link]

WHO., 2016. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. Geneva: WHO. [Link]

Yogman, M., Garfield, C. F. & Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child And Family Health., 2016. Fathers’ roles in the care and development of their children: The role of pediatricians. Pediatrics, 138(1), pp. e20161128. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2016-1128] [PMID]

Zhu, Y., et al., 2024. Implications of perceived empathy from spouses during pregnancy for health-related quality of life among pregnant women: A cross-sectional study in Anhui, China. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 24(1), pp. 269. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-024-06419-w] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2024/11/29 | Accepted: 2025/03/21 | Published: 2025/05/1

Received: 2024/11/29 | Accepted: 2025/03/21 | Published: 2025/05/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |