Wed, Feb 18, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 12, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

JCCNC 2026, 12(1): 87-98 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Menezes Silveira L, Costa Silva S, Lenhari M, Pinto de Melo T, Ruffino-Netto A, Stabile A M. The Influence of Diabetes on Outcomes of Patients With Sepsis. JCCNC 2026; 12 (1) :87-98

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-821-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-821-en.html

Laura Menezes Silveira1

, Simone Costa Silva1

, Simone Costa Silva1

, Mariele Lenhari1

, Mariele Lenhari1

, Thaissa Pinto de Melo1

, Thaissa Pinto de Melo1

, Antônio Ruffino-Netto2

, Antônio Ruffino-Netto2

, Angelita Maria Stabile *3

, Angelita Maria Stabile *3

, Simone Costa Silva1

, Simone Costa Silva1

, Mariele Lenhari1

, Mariele Lenhari1

, Thaissa Pinto de Melo1

, Thaissa Pinto de Melo1

, Antônio Ruffino-Netto2

, Antônio Ruffino-Netto2

, Angelita Maria Stabile *3

, Angelita Maria Stabile *3

1- College of Nursing, University of São Paulo at Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

2- Department of Social Medicine, Hospital of the Ribeirão Preto Medical School, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

3- College of Nursing, University of São Paulo at Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil. ,angelita@eerp.usp.br

2- Department of Social Medicine, Hospital of the Ribeirão Preto Medical School, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

3- College of Nursing, University of São Paulo at Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil. ,

Full-Text [PDF 789 kb]

(189 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (289 Views)

Full-Text: (9 Views)

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common clinical class of diabetes mellitus (DM), present in 90%–95% of cases, usually diagnosed after the age of 40, and associated with population aging, obesity, and physical inactivity. T2DM occurs due to decreased pancreatic beta-cell function, leading to disorders of insulin action and secretion, as well as impaired metabolic responses to insulin. Global statistics show that approximately 537 million people live with DM. By 2045, the prevalence of DM is expected to reach 783 million, with 85% of these people living in low- and middle-income countries (International Diabetes Federation, 2021).

The association between DM and infection is well established clinically and involves several causal pathways, including impaired immune responses in the hyperglycemic environment and altered lipid metabolism. People with DM are nearly twice as likely to be hospitalized and die from infection-related causes as those without DM (Carey et al., 2018). These infections may progress to a condition of greater clinical severity and a higher risk of death, such as sepsis, a condition associated with a higher frequency of hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and glycemic variability (GV) in patients with DM (Hirsch, 2015). Approximately 20% of patients with sepsis also have T2DM (Silveira et al., 2017). Moreover, the combination of DM and sepsis has been associated with worse clinical outcomes, increased infectious complications, and mortality (Frydrych et al., 2017).

Sepsis is the body’s response to infection, during which various unregulated physiological responses lead to organ dysfunction (Singer et al., 2016). The clinical severity of sepsis is associated with high morbidity and mortality, while the costs associated with hospitalization and the complications and organ dysfunctions of sepsis make it a priority public health problem (Reinhart et al., 2017).

A previous study reports that a higher GV and percentage of deaths are observed among patients with DM and sepsis or septic shock than among patients without DM. In this study, patients with DM had a greater need for blood glucose testing and interventions to regulate glucose levels, suggesting an increased demand for care from nursing staff (Silveira et al., 2017).

Nurses directly care for patients with sepsis. When the patient is continuously infused with insulin, more frequent glycemic examinations are required, thereby increasing the nursing team’s workload (Huang et al., 2024). Thus, whether patients with T2DM and sepsis require more time of care from the nursing team should be investigated, because the increased nursing team workload is associated with an increased risk of death in the intensive care units (ICUs) (Lee et al., 2017).

Given the complex nature of sepsis and T2DM, the anticipated increase in the number of people with DM in the coming years, and the greater susceptibility of these individuals to infections, differences in metabolic behaviors that may influence the course and outcome of sepsis should be identified. Therefore, this study aimed to compare clinical outcomes and nursing team workload between patients with sepsis with and without T2DM, and to describe their admission characteristics, clinical progression, and blood glucose levels.

Materials and Methods

Design, setting, and sample

This research was a retrospective cohort study. The study group comprised patients with sepsis and T2DM, and the control group consisted of patients with sepsis and no T2DM, both admitted to the ICU. The study was conducted in a public tertiary hospital that offers highly complex care, located in the countryside of the state of São Paulo, Brazil. The institution consists of 815 general beds and 105 ICU beds, of which 14 are designated for the care of adult clinical and surgical patients.

For both groups, the following candidates were considered eligible: persons aged ≥18 years, of either sex, with a minimum stay of 24 hours in the ICU from January 2015 to December 2018. Pregnant women, immunosuppressed patients (transplanted, presenting malignant neoplastic and/or hematological diseases, and people living with HIV/AIDS), with other types of DM, and patients indicated for palliative treatment at the time of ICU admission were excluded.

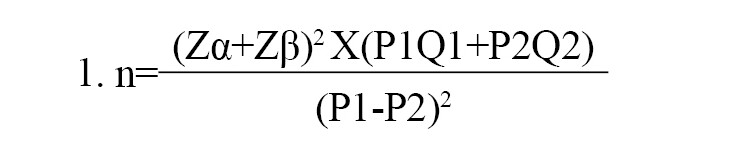

Medical records were intentionally (non-probabilistically) selected, and the number of patients included in the sample was calculated based on the estimated mortality in the experimental group, i.e. patients with sepsis and T2DM (P1=90%), and in the control group, i.e. patients with sepsis without T2DM (P2=70%), considering α=5%, and β=10%, respectively, according to the Equation 1:

The calculation resulted in 78.8 patients. To explore other variables, a sample of 102 patients was used for each group (Figure 1).

Data collection

Data were extracted from physical and electronic medical records and registered in a semi structured form containing the following variables: Sociodemographic data (date of birth, sex, skin color), clinical data upon admission (i.e. up to 24 h after the ICU admission, including the presence of comorbidities such as systemic arterial hypertension, heart disease, dyslipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease), body mass index (BMI), organ dysfunction scores/prognosis as sequential organ failure assessment [SOFA], simplified acute physiology score [SAPS III], and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II [APACHE II]), clinical outcomes (days of ICU stay, date and type of ICU outcome [discharge or death], date and type of hospital outcome [discharge or death], positive culture records, surgical treatment, number of clinical complications, and septic shock), and glycemic data (glycemic records obtained at bedside using a glucometer during the entire ICU stay and the average body glucose levels on admission calculated based on blood glucose values). For the calculation of the nursing activity score (NAS), information was directly collected from the electronic medical record, utilizing data from all ICU admission records (in hours).

Assessment scores and tools

The SOFA score assesses the severity of organ dysfunction in critically ill patients using 6 parameters: Respiratory, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, neurological, and coagulation. Each system receives a score ranging from 0 (normal) to 4 (most altered), yielding a final score of 0 to 24. The calculation considers the worst value observed for each parameter within the first 24 hours after ICU admission (Vincent et al., 1996). The parameters assessed include the ratio of the partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) to the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) (PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio) (respiratory), creatinine (renal), total bilirubin (hepatic), mean arterial pressure, and use/dose of vasoactive drugs (cardiovascular), platelet count (coagulation), and Glasgow coma scale (GCS) (neurological). Each domain with a score of 2 or greater indicates organ dysfunction; the total number of dysfunctions is determined by the number of domains meeting this criterion upon admission. Additionally, the SOFA score is used to monitor clinical progression and estimate prognosis, as higher scores are associated with greater morbidity and mortality. The validity and reliability of this tool in assessing morbidity in critical illness, especially in the context of sepsis and its progression, have been confirmed (Arts et al., 2005).

The SAPS III score is used to assess disease severity and estimate the mortality risk of patients within the first hours of ICU admission. It take into account variables, such as age, prior hospitalization and/or hospital sector, presence of comorbidities, oncology treatments, solid tumors, hematologic cancer, heart failure, cirrhosis, use of vasoactive drugs before ICU admission, type of ICU admission (urgent or scheduled), reason for ICU admission (cardiovascular, hepatic, digestive, neurological, or surgical), and, in the case of surgical reasons, the type of surgery (transplantation, trauma, polytrauma, cardiac surgery, neurosurgery, or other). Additional factors include nosocomial infections, respiratory infections, GCS, systemic blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, PaO₂, PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio, total bilirubin, creatinine, leukocytes, platelets, and pH. For each variable, points are assigned based on predefined physiological ranges and clinical conditions, resulting in a total score typically ranging from 0 to 217. The calculation is based on data obtained in the first hour of ICU admission (Sakr et al., 2008). A higher SAPS III score indicates greater disease severity and a correspondingly increased predicted probability of mortality. Moreover, the SAPS III score demonstrates strong discriminative ability, effectively distinguishing between patients who are likely to survive and those who are likely to progress to death (Ledoux et al., 2008).

The APACHE II score estimates a patient’s prognosis and is calculated from three main components (Knaus et al., 1985). First, an acute physiology score (APS) is derived from the worst values of 12 physiological parameters recorded within the first 24 hours of ICU admission, with points assigned (typically 0-4 per parameter) based on the degree of deviation from predefined normal ranges. Second, an age-adjusted score is added, with increasing points for older age categories. Third, a chronic health score accounts for pre-existing severe organ insufficiency or immunocompromised status. These three component scores are then summed to yield a total APACHE II score, which typically ranges from 0 to 71. Higher scores indicate a greater physiological derangement and a higher predicted risk of mortality. The specific variables contributing to the APS include: Temperature, mean arterial pressure (MAP), respiratory and heart rates, PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio, arterial pH, sodium levels, potassium levels, creatinine, hematocrit, leukocytes, and GCS. In addition to these, age and the presence of chronic diseases are integrated into the total score. APACHE II is a widely validated and robust severity-of-disease classification system, recognized for its good discriminative power and predictive accuracy in estimating mortality for critically ill patients (Ali et al., 2025).

The NAS is divided into 7 major categories and includes 23 items, with weight values ranging from 1.2 to 32.0. The total score represents the percentage of nursing time spent per shift in direct patient care, with a maximum achievable percentage of 176.8%. Each percentage point corresponds to 14.4 minutes of nursing care provided by the nursing team (Miranda et al., 2003; Queijo & Padilha, 2009). It is derived from an instrument translated and validated for use in Brazil (Queijo & Padilha, 2009). This validation study, conducted across 13 Brazilian ICUs, confirmed the instrument’s robust psychometric properties. Specifically, its internal consistency, an important measure of reliability, was demonstrated by the Cronbach α values ranging from 0.79 to 0.82 across its 7 categories. Moreover, construct validity was established through a factorial analysis, which revealed a factor structure consistent with that of the original version. These findings collectively support the NAS as a reliable and valid tool for assessing nursing team workload in the intensive care setting.

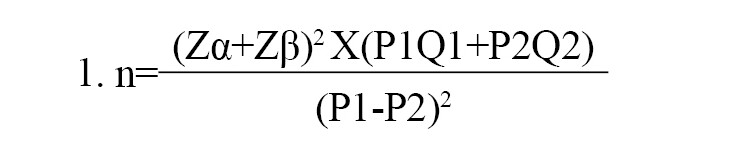

The GV was calculated as the glycemic amplitude, that is, the difference between the lowest and highest blood glucose values. For the standard deviation (SD), the mean of all blood glucose values obtained in each group was calculated, and the differences were squared. The mean of these squared differences was then calculated, and the square root was finally taken. The coefficient of variation (CV%) was calculated by applying the Equation 2:

2. CV%=[standard deviation of blood glucose/mean blood glucose]×100.

Data analysis

The collected data were double-entered into a spreadsheet and, after validation, imported into SPSS software, version 25 (IBM, 2017). Based on descriptive statistics of absolute frequency and relative frequencies, measures of central tendency and variability were performed. To analyze differences between numerical variables, the student t-test or the Mann-Whitney test was used (when the Shapiro–Wilk test indicated a non-normal distribution). For categorical variables, relationships were assessed using the Pearson chi-square test. Statistical significance was considered as P<0.05.

This manuscript was prepared following the recommendations of the STROBE (strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) guidelines.

Results

The sample consisted of 204 patients, 102 for each group. In both groups, the majority were male, white, and aged 60 or older (Table 1). The presence of T2DM was associated with ICU death as an outcome in patients with sepsis (P=0.012). A similar result was observed in relation to the hospital outcome, in which the number of deaths in the group of patients with T2DM was higher when compared to that in the group without T2DM (P=0.033) (Table 1).

The characteristics upon admission and clinical evolution are described in Table 2. The main causes of ICU admission in the T2DM group were septic shock (n=32; 31.5%), sepsis (n=20; 19.9%), and pneumonia (n=7; 7.0%). In the non-T2DM group, these causes were septic shock (n=28; 27.5%), sepsis (n=27; 26.5%), and postoperative complications of neurological surgery (n=8; 7.8%).

In the T2DM group, the main sites of infection were the bloodstream in 54(52.9%) patients, the urinary tract in 39(38.2%), and the respiratory tract in 37(36.3%). Among patients without T2DM, the sites were the bloodstream in 49 patients (48.0%), the urinary tract in 40(39.2%), and the respiratory tract in 29(28.4%). The main microorganisms identified in the T2DM group were Acinetobacter baumannii in 34 patients (33.3%), followed by fungi in 24(21.5%), and Klebsiella pneumoniae in 21(20.6%). In the non-diabetic group, the following were identified: A. baumannii in 38 patients (27.2%), K. pneumoniae in 21(20.6%), Escherichia coli in 18(17.6%), and Staphylococcus aureus in 16(15.7%).

Eighty-two complications registered in the medical records were found, and in both groups, pressure injury was a common complication in the group with T2DM (n=44; 43.1%) and without T2DM (n=32; 31.4%), as well as acute kidney injury requiring dialysis therapy (n=30 [29.4%] and n=29 [28.4%] in the group with and without T2DM, respectively).

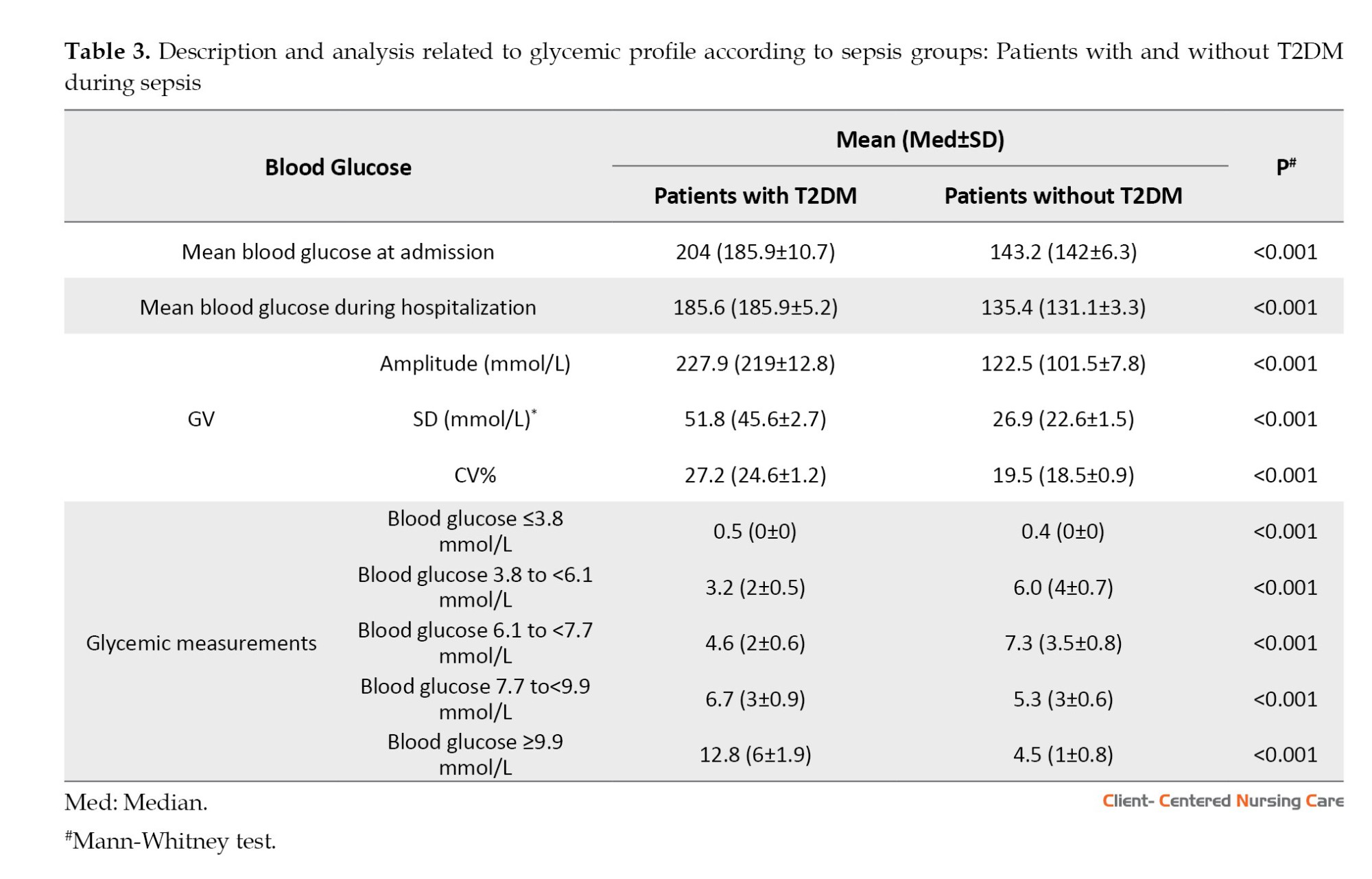

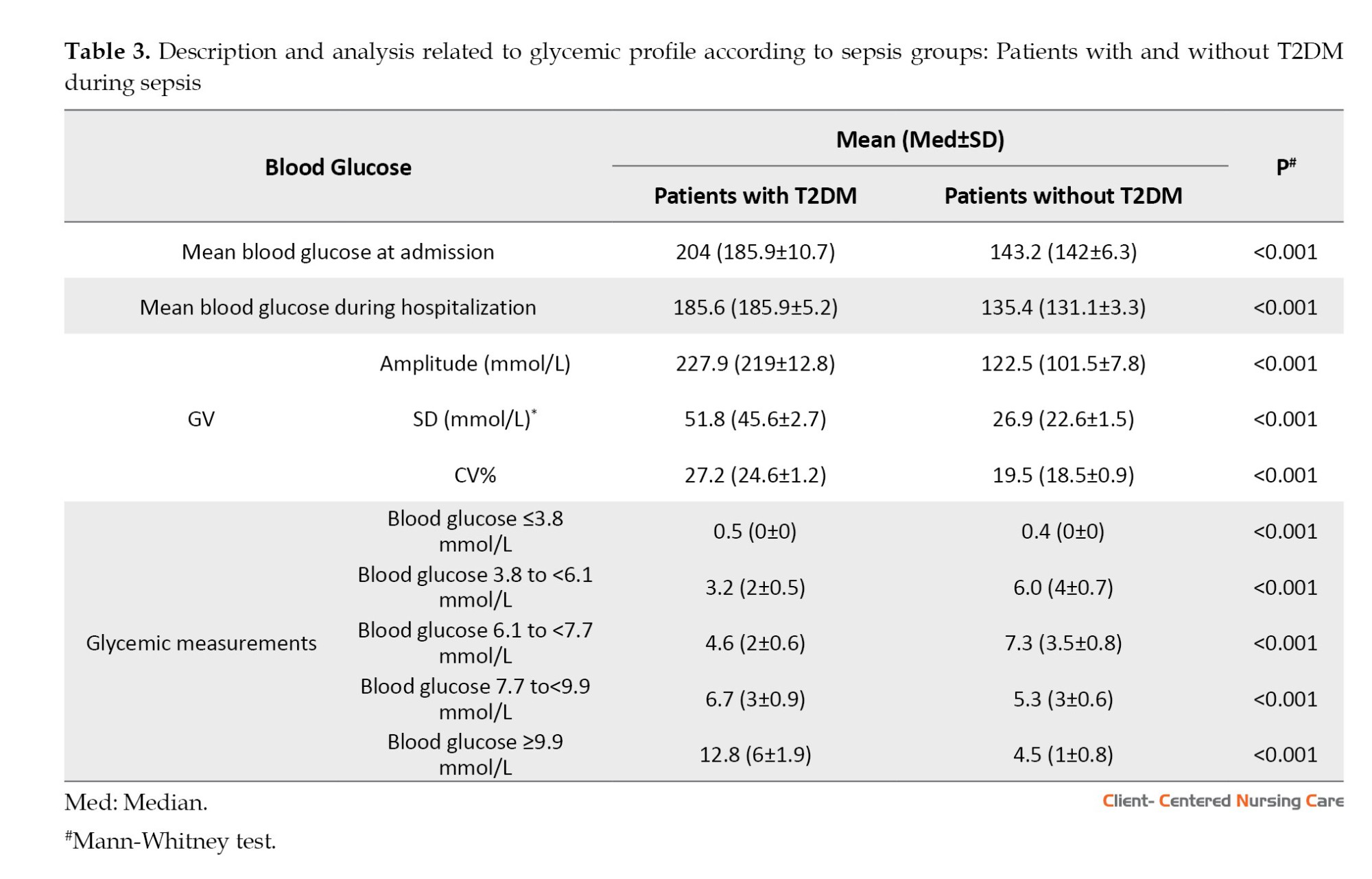

The mean blood glucose upon admission and throughout hospitalization (P=0.000) and the GV (as measured by the methods used for this assessment) (P=0.000) were higher in patients with T2DM than in non-diabetic patients (Table 3).

The NAS did not differ between T2DM and non-diabetic patients (P=0.644); however, the NAS score was associated with mortality in both the T2DM group and the non-diabetic group (P=0.000 and P=0.007, respectively) (Table 4).

Discussion

This study found that the number of deaths, number of comorbidities, severity/prognosis on admission (APACHE II and SAPS III), and glycemic indices were higher in patients with T2DM than in those without T2DM.

For Tiwari et al. (2011), T2DM worsens prognosis and increases morbidity and mortality in infections. However, few specific studies have examined the clinical evolution of patients with sepsis and T2DM, including variables that reflect the complexity of the sepsis clinical picture. The meta-analysis by Wang et al. (2017) on sepsis and DM suggested that DM does not affect outcomes in patients with sepsis. However, in this review (Wang et al., 2017), the authors included 10 articles in the analysis, and of these, only 5 specified the type of DM as type 2, thereby hindering the generalizability of the conclusions.

No significant age-related differences were found between patients with and without T2DM; however, the T2DM group had more comorbidities and higher BMI. Our findings are in line with other studies that have examined the presence of overweight and comorbidities in patients with T2DM. A study on 1104 patients with sepsis, of whom 241(21.8%) had DM, found that patients with T2DM were older and had a higher BMI (Van Vught et al., 2016). Additionally, patients with T2DM had a high prevalence of comorbidities. A study by Li et al. (2021) reveals that while the number of comorbidities increased with age, a high prevalence was already present across nearly all age groups (e.g. 80% in those aged 18–39 y and 91% in those aged 40–59 y). This finding suggests that T2DM is generally associated with a substantial burden of chronic conditions, irrespective of age. These findings highlight the significant impact of T2DM on patients’ overall health, reinforcing its pervasive association with comorbidities and elevated BMI across all age groups.

Obesity is one of the main factors in the development of T2DM. Patients with obesity and patients with DM are more susceptible to infections and are more likely to develop complications from infections (Yang et al., 2020). Although obesity is considered a risk factor for sepsis, a multicenter study showed that those who were obese received lower doses of antimicrobial agents, lower fluid volumes, and had lower hospital mortality (Arabi et al., 2013). Another study showed that morbid obesity was a protective factor against death from sepsis (Kuperman et al., 2013).

In contrast, studies have shown that obesity can aggravate sepsis by increasing oxidative stress, which can cause brain (Vieira et al., 2015), lung, and liver damage (Petronilho et al., 2016), leading to worse outcomes (Papadimitriou-Olivgeris et al., 2016). Thus, whether obesity in patients with DM is a protective factor during sepsis, and or whether there is an inherent mechanism in patients with DM and obesity capable of modifying the prognosis of sepsis, should be clarified.

The T2DM group had more positive microbiological cultures than the non-T2DM group. Other studies also reported a similar finding: High infection rates in the DM group (Carey et al., 2018).

A. baumannii is a prevalent pathogen in hospitals, easily adapting to the environment, commonly resistant to available antimicrobials, and associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Ballouz et al., 2017). Infection with this organism is associated with prolonged use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, prolonged hospitalization, patient severity (Gulen et al., 2015), sepsis development (Freire et al., 2016), and inappropriate antimicrobial therapy in patients with sepsis (Shorr et al., 2014).

In the T2DM group, fungi were the second-most frequently recorded microorganisms in cultures. Although other risk factors are associated with fungal infection in critically ill patients, Singh et al. (2016) found that DM may be an independent risk factor, and patients with T2DM are twice as likely to acquire a fungal infection as those without T2DM.

Studies suggest that respiratory, skin, soft tissue, urinary tract, genital, and perineal infections in people with DM are associated with inadequate glycemic control (Hine et al., 2017). Thus, glycemic control in the context of DM and infections should be considered a practice valued by the multidisciplinary team, both to prevent infections that can trigger sepsis and to monitor patients with sepsis who may acquire new infections.

Most frequently reported complications in both groups were pressure injury and acute kidney injury. Hemodynamic instability (mean arterial pressure, ≤65 mm Hg) indicates insufficient peripheral circulation and tissue perfusion (Engels et al., 2016). People with DM are more susceptible to the development of wounds (Cox & Roche, 2015) due to vascular (macroangiopathy and microangiopathy) and metabolic (hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia) changes (Zambonato et al., 2013).

In relation to acute kidney injury, sepsis is one of the main risk factors for its development. Patients with DM often have other health problems in addition to DM, such as dyslipidemia, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. These problems increase the chance of acute kidney injury in critical conditions (Poston & Koyner, 2019). A French case-control study demonstrated that DM is not associated with acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis or septic shock. However, it represents an independent risk factor for persistent renal dysfunction in patients with acute kidney injury in the ICU who, even after discharge, show creatinine levels above normal parameters (Venot et al., 2015).

Regarding glycemic variables, the mean, amplitude, standard deviation, and CV% of blood glucose values were higher in the T2DM group than in the non-T2DM group. Previous studies present similar findings (Silveira et al., 2017; Krinsley et al., 2013). Blood glucose instability in patients with DM requires more attention from the healthcare team because blood glucose fluctuations play a significant role in vascular endothelial dysfunction, the onset of cardiovascular events (Torimoto et al., 2013), increased oxidative stress, and modification of the kidney structure and function, with consequently increased creatinine levels (Ying et al., 2016). Moreover, GV is associated with a longer hospital stay (Mendez et al., 2013).

Currently, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Diabetes Association propose glycemic targets of 7.7-9.9 mmol/L for critically ill patients, regardless of whether DM is present, avoiding blood glucose levels <5.5 mmol/L (Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes, 2015). The Surviving Sepsis Campaign guideline recommends maintaining blood glucose levels between 7.8 and 9.9 mmol/L (Evans et al., 2021).

Regarding the GV measurements, the mean CV% was 29.8% in patients with T2DM and 22.4% in those without T2DM. Every 10% increase in CV% of blood glucose levels is estimated to increase the risk of death by 1.2 times in critically ill patients. The CV% of glycemia has been associated with mortality, regardless of age, disease severity, DM, and hypoglycemia (Lanspa et al., 2013). In critically ill patients without DM, the risk of death is higher than in those with DM (odds ratio, 1.3 vs 1.1), respectively (Lanspa et al., 2013). The SD was also higher in patients with T2DM. Blood glucose SD values >2.7 mmol/L indicate high GV, i.e. greater blood glucose instability. The Brazilian Society of Diabetes (Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes, 2019) recommends that SD be <2.8 mmol/L or no more than 1/3 of the mean blood glucose.

Previous studies have shown that patients with DM tolerate a wider range of blood glucose levels than patients without DM (Sechterberger et al., 2013). From this perspective, DM is considered a protective factor against the risk of death in critically ill patients (Krinsley et al., 2013). However, this study shows a higher GV and a higher occurrence of deaths in patients with T2DM. Blood glucose control is important for all patients with sepsis, regardless of whether they have T2DM. The health team should be aware of patients with sepsis’ glycemic levels and continually reevaluate control procedures.

Other authors infer that hyperglycemia (blood glucose >11.1 mmol/L) at ICU admission is common in patients with sepsis and is associated with increased mortality up to 30 days post-admission, regardless of T2DM status (Van Vught, 2017). One study showed that during sepsis, hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, and GV are independent risk factors for death during hospitalization (Chao et al., 2017). Moreover, the high mortality rate in patients with DM may be associated with immunological characteristics of T2DM, such as increased levels of C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8, which can lead to abnormalities in the response to infections (Koh et al., 2012).

Regarding the workload and time demands of the nursing staff, the study found no differences between groups. However, the mean NAS in this study was 89.1% for patients with T2DM and 88.6% for those without T2DM, representing about 21 h of care and indicating a high work demand for professionals. The average workload was found to be higher than that presented in other ICU studies, where NAS averages ranged from 70% to 79% (Nassiff et al., 2018; Padilha et al., 2015), which may have implications for the number of professionals involved in care. Furthermore, NAS was associated with death in groups with and without T2DM. The association between the NAS and mortality has been the subject of ICU studies, indicating that the mean NAS is higher in patients who progress to death compared to those who survive. Higher NAS values reflect greater clinical complexity and severity, as more critically ill patients, including those with sepsis, require increased monitoring, therapeutic interventions, and invasive support, thereby raising the demands on the nursing team. This increased nursing workload correlates with negative outcomes, including a higher risk of death (Ross et al., 2025). Another study reinforces this, showing that although the mean NAS during the first 24 hours is elevated in ICUs with many cases of sepsis, the hypothesis that a high workload is an independent predictor of mortality may vary with clinical severity, as measured by other scores (e.g. APACHE II). Nevertheless, high NAS values are generally associated with greater risk and complexity, which are common in sepsis cases (Nassif et al., 2018).

Some limitations of this study should be noted, particularly the retrospective design and the collection of data from medical records, where data quality is not controlled; therefore, the study is subject to information bias. However, studies designed specifically for outcome analysis in patients with and without T2DM are few. Thus, the present study is expected to expand knowledge of the particularities of patients with T2DM and sepsis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patients with T2DM and sepsis had worse ICU and hospital outcomes, presented more severe conditions, had a higher number of infections, and had a higher GV during sepsis. The workload and length of nursing care are similar in the group of patients with sepsis. Evidence from this study is expected to clarify further the role of T2DM in the clinical course of patients with sepsis. As the health team increases its knowledge, it can propose improvements by refining the care it offers.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of São Paulo at Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil (No. 5.776.917, September 29, 2022), with the need for written informed consent waived, as we used secondary data.

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) - Financing Code 001 (CAPES is a Brazilian governmental agency that organizes and regulates graduate programs in Brazil, but it is not a research funding agency).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Laura Menezes Silveira, Antônio Ruffino-Netto, and Angelita Maria Stabile; Data acquisition: Laura Menezes Silveira, Simone Costa Silva, and Mariele Lenhari; Analysis and data interpretation: Laura Menezes Silveira and Angelita Maria Stabile; Writing the original draft: Laura Menezes Silveira, Pinto de Melo, and Angelita Maria Stabile; Review and editing: Simone Costa Silva, Mariele Lenhari, Pinto de Melo, and Antônio Ruffino-Netto; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for the scholarship granted to the main researcher.

References

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common clinical class of diabetes mellitus (DM), present in 90%–95% of cases, usually diagnosed after the age of 40, and associated with population aging, obesity, and physical inactivity. T2DM occurs due to decreased pancreatic beta-cell function, leading to disorders of insulin action and secretion, as well as impaired metabolic responses to insulin. Global statistics show that approximately 537 million people live with DM. By 2045, the prevalence of DM is expected to reach 783 million, with 85% of these people living in low- and middle-income countries (International Diabetes Federation, 2021).

The association between DM and infection is well established clinically and involves several causal pathways, including impaired immune responses in the hyperglycemic environment and altered lipid metabolism. People with DM are nearly twice as likely to be hospitalized and die from infection-related causes as those without DM (Carey et al., 2018). These infections may progress to a condition of greater clinical severity and a higher risk of death, such as sepsis, a condition associated with a higher frequency of hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and glycemic variability (GV) in patients with DM (Hirsch, 2015). Approximately 20% of patients with sepsis also have T2DM (Silveira et al., 2017). Moreover, the combination of DM and sepsis has been associated with worse clinical outcomes, increased infectious complications, and mortality (Frydrych et al., 2017).

Sepsis is the body’s response to infection, during which various unregulated physiological responses lead to organ dysfunction (Singer et al., 2016). The clinical severity of sepsis is associated with high morbidity and mortality, while the costs associated with hospitalization and the complications and organ dysfunctions of sepsis make it a priority public health problem (Reinhart et al., 2017).

A previous study reports that a higher GV and percentage of deaths are observed among patients with DM and sepsis or septic shock than among patients without DM. In this study, patients with DM had a greater need for blood glucose testing and interventions to regulate glucose levels, suggesting an increased demand for care from nursing staff (Silveira et al., 2017).

Nurses directly care for patients with sepsis. When the patient is continuously infused with insulin, more frequent glycemic examinations are required, thereby increasing the nursing team’s workload (Huang et al., 2024). Thus, whether patients with T2DM and sepsis require more time of care from the nursing team should be investigated, because the increased nursing team workload is associated with an increased risk of death in the intensive care units (ICUs) (Lee et al., 2017).

Given the complex nature of sepsis and T2DM, the anticipated increase in the number of people with DM in the coming years, and the greater susceptibility of these individuals to infections, differences in metabolic behaviors that may influence the course and outcome of sepsis should be identified. Therefore, this study aimed to compare clinical outcomes and nursing team workload between patients with sepsis with and without T2DM, and to describe their admission characteristics, clinical progression, and blood glucose levels.

Materials and Methods

Design, setting, and sample

This research was a retrospective cohort study. The study group comprised patients with sepsis and T2DM, and the control group consisted of patients with sepsis and no T2DM, both admitted to the ICU. The study was conducted in a public tertiary hospital that offers highly complex care, located in the countryside of the state of São Paulo, Brazil. The institution consists of 815 general beds and 105 ICU beds, of which 14 are designated for the care of adult clinical and surgical patients.

For both groups, the following candidates were considered eligible: persons aged ≥18 years, of either sex, with a minimum stay of 24 hours in the ICU from January 2015 to December 2018. Pregnant women, immunosuppressed patients (transplanted, presenting malignant neoplastic and/or hematological diseases, and people living with HIV/AIDS), with other types of DM, and patients indicated for palliative treatment at the time of ICU admission were excluded.

Medical records were intentionally (non-probabilistically) selected, and the number of patients included in the sample was calculated based on the estimated mortality in the experimental group, i.e. patients with sepsis and T2DM (P1=90%), and in the control group, i.e. patients with sepsis without T2DM (P2=70%), considering α=5%, and β=10%, respectively, according to the Equation 1:

The calculation resulted in 78.8 patients. To explore other variables, a sample of 102 patients was used for each group (Figure 1).

Data collection

Data were extracted from physical and electronic medical records and registered in a semi structured form containing the following variables: Sociodemographic data (date of birth, sex, skin color), clinical data upon admission (i.e. up to 24 h after the ICU admission, including the presence of comorbidities such as systemic arterial hypertension, heart disease, dyslipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease), body mass index (BMI), organ dysfunction scores/prognosis as sequential organ failure assessment [SOFA], simplified acute physiology score [SAPS III], and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II [APACHE II]), clinical outcomes (days of ICU stay, date and type of ICU outcome [discharge or death], date and type of hospital outcome [discharge or death], positive culture records, surgical treatment, number of clinical complications, and septic shock), and glycemic data (glycemic records obtained at bedside using a glucometer during the entire ICU stay and the average body glucose levels on admission calculated based on blood glucose values). For the calculation of the nursing activity score (NAS), information was directly collected from the electronic medical record, utilizing data from all ICU admission records (in hours).

Assessment scores and tools

The SOFA score assesses the severity of organ dysfunction in critically ill patients using 6 parameters: Respiratory, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, neurological, and coagulation. Each system receives a score ranging from 0 (normal) to 4 (most altered), yielding a final score of 0 to 24. The calculation considers the worst value observed for each parameter within the first 24 hours after ICU admission (Vincent et al., 1996). The parameters assessed include the ratio of the partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) to the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) (PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio) (respiratory), creatinine (renal), total bilirubin (hepatic), mean arterial pressure, and use/dose of vasoactive drugs (cardiovascular), platelet count (coagulation), and Glasgow coma scale (GCS) (neurological). Each domain with a score of 2 or greater indicates organ dysfunction; the total number of dysfunctions is determined by the number of domains meeting this criterion upon admission. Additionally, the SOFA score is used to monitor clinical progression and estimate prognosis, as higher scores are associated with greater morbidity and mortality. The validity and reliability of this tool in assessing morbidity in critical illness, especially in the context of sepsis and its progression, have been confirmed (Arts et al., 2005).

The SAPS III score is used to assess disease severity and estimate the mortality risk of patients within the first hours of ICU admission. It take into account variables, such as age, prior hospitalization and/or hospital sector, presence of comorbidities, oncology treatments, solid tumors, hematologic cancer, heart failure, cirrhosis, use of vasoactive drugs before ICU admission, type of ICU admission (urgent or scheduled), reason for ICU admission (cardiovascular, hepatic, digestive, neurological, or surgical), and, in the case of surgical reasons, the type of surgery (transplantation, trauma, polytrauma, cardiac surgery, neurosurgery, or other). Additional factors include nosocomial infections, respiratory infections, GCS, systemic blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, PaO₂, PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio, total bilirubin, creatinine, leukocytes, platelets, and pH. For each variable, points are assigned based on predefined physiological ranges and clinical conditions, resulting in a total score typically ranging from 0 to 217. The calculation is based on data obtained in the first hour of ICU admission (Sakr et al., 2008). A higher SAPS III score indicates greater disease severity and a correspondingly increased predicted probability of mortality. Moreover, the SAPS III score demonstrates strong discriminative ability, effectively distinguishing between patients who are likely to survive and those who are likely to progress to death (Ledoux et al., 2008).

The APACHE II score estimates a patient’s prognosis and is calculated from three main components (Knaus et al., 1985). First, an acute physiology score (APS) is derived from the worst values of 12 physiological parameters recorded within the first 24 hours of ICU admission, with points assigned (typically 0-4 per parameter) based on the degree of deviation from predefined normal ranges. Second, an age-adjusted score is added, with increasing points for older age categories. Third, a chronic health score accounts for pre-existing severe organ insufficiency or immunocompromised status. These three component scores are then summed to yield a total APACHE II score, which typically ranges from 0 to 71. Higher scores indicate a greater physiological derangement and a higher predicted risk of mortality. The specific variables contributing to the APS include: Temperature, mean arterial pressure (MAP), respiratory and heart rates, PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio, arterial pH, sodium levels, potassium levels, creatinine, hematocrit, leukocytes, and GCS. In addition to these, age and the presence of chronic diseases are integrated into the total score. APACHE II is a widely validated and robust severity-of-disease classification system, recognized for its good discriminative power and predictive accuracy in estimating mortality for critically ill patients (Ali et al., 2025).

The NAS is divided into 7 major categories and includes 23 items, with weight values ranging from 1.2 to 32.0. The total score represents the percentage of nursing time spent per shift in direct patient care, with a maximum achievable percentage of 176.8%. Each percentage point corresponds to 14.4 minutes of nursing care provided by the nursing team (Miranda et al., 2003; Queijo & Padilha, 2009). It is derived from an instrument translated and validated for use in Brazil (Queijo & Padilha, 2009). This validation study, conducted across 13 Brazilian ICUs, confirmed the instrument’s robust psychometric properties. Specifically, its internal consistency, an important measure of reliability, was demonstrated by the Cronbach α values ranging from 0.79 to 0.82 across its 7 categories. Moreover, construct validity was established through a factorial analysis, which revealed a factor structure consistent with that of the original version. These findings collectively support the NAS as a reliable and valid tool for assessing nursing team workload in the intensive care setting.

The GV was calculated as the glycemic amplitude, that is, the difference between the lowest and highest blood glucose values. For the standard deviation (SD), the mean of all blood glucose values obtained in each group was calculated, and the differences were squared. The mean of these squared differences was then calculated, and the square root was finally taken. The coefficient of variation (CV%) was calculated by applying the Equation 2:

2. CV%=[standard deviation of blood glucose/mean blood glucose]×100.

Data analysis

The collected data were double-entered into a spreadsheet and, after validation, imported into SPSS software, version 25 (IBM, 2017). Based on descriptive statistics of absolute frequency and relative frequencies, measures of central tendency and variability were performed. To analyze differences between numerical variables, the student t-test or the Mann-Whitney test was used (when the Shapiro–Wilk test indicated a non-normal distribution). For categorical variables, relationships were assessed using the Pearson chi-square test. Statistical significance was considered as P<0.05.

This manuscript was prepared following the recommendations of the STROBE (strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) guidelines.

Results

The sample consisted of 204 patients, 102 for each group. In both groups, the majority were male, white, and aged 60 or older (Table 1). The presence of T2DM was associated with ICU death as an outcome in patients with sepsis (P=0.012). A similar result was observed in relation to the hospital outcome, in which the number of deaths in the group of patients with T2DM was higher when compared to that in the group without T2DM (P=0.033) (Table 1).

The characteristics upon admission and clinical evolution are described in Table 2. The main causes of ICU admission in the T2DM group were septic shock (n=32; 31.5%), sepsis (n=20; 19.9%), and pneumonia (n=7; 7.0%). In the non-T2DM group, these causes were septic shock (n=28; 27.5%), sepsis (n=27; 26.5%), and postoperative complications of neurological surgery (n=8; 7.8%).

In the T2DM group, the main sites of infection were the bloodstream in 54(52.9%) patients, the urinary tract in 39(38.2%), and the respiratory tract in 37(36.3%). Among patients without T2DM, the sites were the bloodstream in 49 patients (48.0%), the urinary tract in 40(39.2%), and the respiratory tract in 29(28.4%). The main microorganisms identified in the T2DM group were Acinetobacter baumannii in 34 patients (33.3%), followed by fungi in 24(21.5%), and Klebsiella pneumoniae in 21(20.6%). In the non-diabetic group, the following were identified: A. baumannii in 38 patients (27.2%), K. pneumoniae in 21(20.6%), Escherichia coli in 18(17.6%), and Staphylococcus aureus in 16(15.7%).

Eighty-two complications registered in the medical records were found, and in both groups, pressure injury was a common complication in the group with T2DM (n=44; 43.1%) and without T2DM (n=32; 31.4%), as well as acute kidney injury requiring dialysis therapy (n=30 [29.4%] and n=29 [28.4%] in the group with and without T2DM, respectively).

The mean blood glucose upon admission and throughout hospitalization (P=0.000) and the GV (as measured by the methods used for this assessment) (P=0.000) were higher in patients with T2DM than in non-diabetic patients (Table 3).

The NAS did not differ between T2DM and non-diabetic patients (P=0.644); however, the NAS score was associated with mortality in both the T2DM group and the non-diabetic group (P=0.000 and P=0.007, respectively) (Table 4).

Discussion

This study found that the number of deaths, number of comorbidities, severity/prognosis on admission (APACHE II and SAPS III), and glycemic indices were higher in patients with T2DM than in those without T2DM.

For Tiwari et al. (2011), T2DM worsens prognosis and increases morbidity and mortality in infections. However, few specific studies have examined the clinical evolution of patients with sepsis and T2DM, including variables that reflect the complexity of the sepsis clinical picture. The meta-analysis by Wang et al. (2017) on sepsis and DM suggested that DM does not affect outcomes in patients with sepsis. However, in this review (Wang et al., 2017), the authors included 10 articles in the analysis, and of these, only 5 specified the type of DM as type 2, thereby hindering the generalizability of the conclusions.

No significant age-related differences were found between patients with and without T2DM; however, the T2DM group had more comorbidities and higher BMI. Our findings are in line with other studies that have examined the presence of overweight and comorbidities in patients with T2DM. A study on 1104 patients with sepsis, of whom 241(21.8%) had DM, found that patients with T2DM were older and had a higher BMI (Van Vught et al., 2016). Additionally, patients with T2DM had a high prevalence of comorbidities. A study by Li et al. (2021) reveals that while the number of comorbidities increased with age, a high prevalence was already present across nearly all age groups (e.g. 80% in those aged 18–39 y and 91% in those aged 40–59 y). This finding suggests that T2DM is generally associated with a substantial burden of chronic conditions, irrespective of age. These findings highlight the significant impact of T2DM on patients’ overall health, reinforcing its pervasive association with comorbidities and elevated BMI across all age groups.

Obesity is one of the main factors in the development of T2DM. Patients with obesity and patients with DM are more susceptible to infections and are more likely to develop complications from infections (Yang et al., 2020). Although obesity is considered a risk factor for sepsis, a multicenter study showed that those who were obese received lower doses of antimicrobial agents, lower fluid volumes, and had lower hospital mortality (Arabi et al., 2013). Another study showed that morbid obesity was a protective factor against death from sepsis (Kuperman et al., 2013).

In contrast, studies have shown that obesity can aggravate sepsis by increasing oxidative stress, which can cause brain (Vieira et al., 2015), lung, and liver damage (Petronilho et al., 2016), leading to worse outcomes (Papadimitriou-Olivgeris et al., 2016). Thus, whether obesity in patients with DM is a protective factor during sepsis, and or whether there is an inherent mechanism in patients with DM and obesity capable of modifying the prognosis of sepsis, should be clarified.

The T2DM group had more positive microbiological cultures than the non-T2DM group. Other studies also reported a similar finding: High infection rates in the DM group (Carey et al., 2018).

A. baumannii is a prevalent pathogen in hospitals, easily adapting to the environment, commonly resistant to available antimicrobials, and associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Ballouz et al., 2017). Infection with this organism is associated with prolonged use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, prolonged hospitalization, patient severity (Gulen et al., 2015), sepsis development (Freire et al., 2016), and inappropriate antimicrobial therapy in patients with sepsis (Shorr et al., 2014).

In the T2DM group, fungi were the second-most frequently recorded microorganisms in cultures. Although other risk factors are associated with fungal infection in critically ill patients, Singh et al. (2016) found that DM may be an independent risk factor, and patients with T2DM are twice as likely to acquire a fungal infection as those without T2DM.

Studies suggest that respiratory, skin, soft tissue, urinary tract, genital, and perineal infections in people with DM are associated with inadequate glycemic control (Hine et al., 2017). Thus, glycemic control in the context of DM and infections should be considered a practice valued by the multidisciplinary team, both to prevent infections that can trigger sepsis and to monitor patients with sepsis who may acquire new infections.

Most frequently reported complications in both groups were pressure injury and acute kidney injury. Hemodynamic instability (mean arterial pressure, ≤65 mm Hg) indicates insufficient peripheral circulation and tissue perfusion (Engels et al., 2016). People with DM are more susceptible to the development of wounds (Cox & Roche, 2015) due to vascular (macroangiopathy and microangiopathy) and metabolic (hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia) changes (Zambonato et al., 2013).

In relation to acute kidney injury, sepsis is one of the main risk factors for its development. Patients with DM often have other health problems in addition to DM, such as dyslipidemia, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. These problems increase the chance of acute kidney injury in critical conditions (Poston & Koyner, 2019). A French case-control study demonstrated that DM is not associated with acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis or septic shock. However, it represents an independent risk factor for persistent renal dysfunction in patients with acute kidney injury in the ICU who, even after discharge, show creatinine levels above normal parameters (Venot et al., 2015).

Regarding glycemic variables, the mean, amplitude, standard deviation, and CV% of blood glucose values were higher in the T2DM group than in the non-T2DM group. Previous studies present similar findings (Silveira et al., 2017; Krinsley et al., 2013). Blood glucose instability in patients with DM requires more attention from the healthcare team because blood glucose fluctuations play a significant role in vascular endothelial dysfunction, the onset of cardiovascular events (Torimoto et al., 2013), increased oxidative stress, and modification of the kidney structure and function, with consequently increased creatinine levels (Ying et al., 2016). Moreover, GV is associated with a longer hospital stay (Mendez et al., 2013).

Currently, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Diabetes Association propose glycemic targets of 7.7-9.9 mmol/L for critically ill patients, regardless of whether DM is present, avoiding blood glucose levels <5.5 mmol/L (Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes, 2015). The Surviving Sepsis Campaign guideline recommends maintaining blood glucose levels between 7.8 and 9.9 mmol/L (Evans et al., 2021).

Regarding the GV measurements, the mean CV% was 29.8% in patients with T2DM and 22.4% in those without T2DM. Every 10% increase in CV% of blood glucose levels is estimated to increase the risk of death by 1.2 times in critically ill patients. The CV% of glycemia has been associated with mortality, regardless of age, disease severity, DM, and hypoglycemia (Lanspa et al., 2013). In critically ill patients without DM, the risk of death is higher than in those with DM (odds ratio, 1.3 vs 1.1), respectively (Lanspa et al., 2013). The SD was also higher in patients with T2DM. Blood glucose SD values >2.7 mmol/L indicate high GV, i.e. greater blood glucose instability. The Brazilian Society of Diabetes (Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes, 2019) recommends that SD be <2.8 mmol/L or no more than 1/3 of the mean blood glucose.

Previous studies have shown that patients with DM tolerate a wider range of blood glucose levels than patients without DM (Sechterberger et al., 2013). From this perspective, DM is considered a protective factor against the risk of death in critically ill patients (Krinsley et al., 2013). However, this study shows a higher GV and a higher occurrence of deaths in patients with T2DM. Blood glucose control is important for all patients with sepsis, regardless of whether they have T2DM. The health team should be aware of patients with sepsis’ glycemic levels and continually reevaluate control procedures.

Other authors infer that hyperglycemia (blood glucose >11.1 mmol/L) at ICU admission is common in patients with sepsis and is associated with increased mortality up to 30 days post-admission, regardless of T2DM status (Van Vught, 2017). One study showed that during sepsis, hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, and GV are independent risk factors for death during hospitalization (Chao et al., 2017). Moreover, the high mortality rate in patients with DM may be associated with immunological characteristics of T2DM, such as increased levels of C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8, which can lead to abnormalities in the response to infections (Koh et al., 2012).

Regarding the workload and time demands of the nursing staff, the study found no differences between groups. However, the mean NAS in this study was 89.1% for patients with T2DM and 88.6% for those without T2DM, representing about 21 h of care and indicating a high work demand for professionals. The average workload was found to be higher than that presented in other ICU studies, where NAS averages ranged from 70% to 79% (Nassiff et al., 2018; Padilha et al., 2015), which may have implications for the number of professionals involved in care. Furthermore, NAS was associated with death in groups with and without T2DM. The association between the NAS and mortality has been the subject of ICU studies, indicating that the mean NAS is higher in patients who progress to death compared to those who survive. Higher NAS values reflect greater clinical complexity and severity, as more critically ill patients, including those with sepsis, require increased monitoring, therapeutic interventions, and invasive support, thereby raising the demands on the nursing team. This increased nursing workload correlates with negative outcomes, including a higher risk of death (Ross et al., 2025). Another study reinforces this, showing that although the mean NAS during the first 24 hours is elevated in ICUs with many cases of sepsis, the hypothesis that a high workload is an independent predictor of mortality may vary with clinical severity, as measured by other scores (e.g. APACHE II). Nevertheless, high NAS values are generally associated with greater risk and complexity, which are common in sepsis cases (Nassif et al., 2018).

Some limitations of this study should be noted, particularly the retrospective design and the collection of data from medical records, where data quality is not controlled; therefore, the study is subject to information bias. However, studies designed specifically for outcome analysis in patients with and without T2DM are few. Thus, the present study is expected to expand knowledge of the particularities of patients with T2DM and sepsis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patients with T2DM and sepsis had worse ICU and hospital outcomes, presented more severe conditions, had a higher number of infections, and had a higher GV during sepsis. The workload and length of nursing care are similar in the group of patients with sepsis. Evidence from this study is expected to clarify further the role of T2DM in the clinical course of patients with sepsis. As the health team increases its knowledge, it can propose improvements by refining the care it offers.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of São Paulo at Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil (No. 5.776.917, September 29, 2022), with the need for written informed consent waived, as we used secondary data.

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) - Financing Code 001 (CAPES is a Brazilian governmental agency that organizes and regulates graduate programs in Brazil, but it is not a research funding agency).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Laura Menezes Silveira, Antônio Ruffino-Netto, and Angelita Maria Stabile; Data acquisition: Laura Menezes Silveira, Simone Costa Silva, and Mariele Lenhari; Analysis and data interpretation: Laura Menezes Silveira and Angelita Maria Stabile; Writing the original draft: Laura Menezes Silveira, Pinto de Melo, and Angelita Maria Stabile; Review and editing: Simone Costa Silva, Mariele Lenhari, Pinto de Melo, and Antônio Ruffino-Netto; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for the scholarship granted to the main researcher.

References

Ali, A. H. D., et al., 2025. Discriminatory Performance of APACHE II Score and the Prediction of Mortality within the ICU in Patients with Sepsis Admitted to the ICU. Materia Socio-Medica, 37(2), pp. 153-8. [DOI:10.5455/msm.2025.37.153-158] [PMID]

Arabi, Y. M., et al., 2013. Clinical characteristics, sepsis interventions and outcomes in the obese patients with septic shock: An international multicenter cohort study. Critical Care, 17(2), pp. R72. [DOI:10.1186/cc12680] [PMID]

Arts, D. G., et al., 2005. Reliability and accuracy of Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scoring. Critical Care Medicine, 33(9), pp. 1988-93. [DOI:10.1097/01.CCM.0000178178.02574.AB] [PMID]

Ballouz, T., et al., 2017. Risk factors, clinical presentation, and outcome of Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 4(7), pp. 156. [DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2017.00156] [PMID]

Carey, I. M., et al., 2018. Risk of infection in type 1 and type 2 diabetes compared with the general population: A matched cohort study. Diabetes Care, 41(3), pp. 513-21. [DOI:10.2337/dc17-2131] [PMID]

Chao, H. Y., et al., 2017. Association of in-hospital mortality and dysglycemia in septic patients. PLoS One, 12(1), pp. e0170408. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0170408] [PMID]

Cox, J. & Roche, S., 2015. Vasopressors and development of pressure ulcers in adult critical care patients. American Journal of Critical Care, 24(6), pp. 501-10. [DOI:10.4037/ajcc2015123]] [PMID]

Engels, D., et al., 2016. Pressure ulcers: Factors contributing to their development in the OR. AORN Journal, 103(3), pp. 271-81. [DOI:10.1016/j.aorn.2016.01.008] [PMID]

Evans, L., et al., 2021. Surviving sepsis campaign: International Guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Medicine, 47(1)1, pp. 1181-247. [DOI:10.1007/s00134-021-06506-y] [PMID]

Freire, M. P., et al., 2016. Bloodstream infection caused by extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in cancer patients: high mortality associated with delayed treatment rather than with the degree of neutropenia. Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 22(4), pp. 352-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.010] [PMID]

Frydrych, L. M., et al., 2017. Diabetes and sepsis: Risk, recurrence, and ruination. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 30(8), pp. 271. [DOI:10.3389/fendo.2017.00271] [PMID]

Gulen, T. A., et al., 2015. Clinical importance and cost of bacteremia caused by nosocomial multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 38, pp. 32-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2015.06.014] [PMID]

Hine, J. L., et al., 2017. Association between glycaemic control and common infections in people with Type 2 diabetes: A cohort study. Diabetic Medicine, 34(4), pp. 551-7. [DOI:10.1111/dme.13205] [PMID]

Hirsch, I. B., 2015. Glycemic variability and diabetes complications: Does it matter? Of course it does! Diabetes Care, 38(8), pp. 1610-4. [DOI:10.2337/dc14-2898] [PMID]

Huang, M., et al., 2024. Insulin infusion protocols for blood glucose management in critically Ill Patients: A scoping review. Critical Care Nurse, 44(1), pp. 21-32. [DOI:10.4037/ccn2024427] [PMID]

International Diabetes Federation., 2021. IDF Diabetes Atlas (10th ed.). Brussels, Belgium:International Diabetes Federation. [Link]

Knaus, W. A., et al., 1985. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Critical Care Medicine, 13(10), pp. 818-29. [DOI:10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009] [PMID]

Koh, G. C., et al., 2012. The impact of diabetes on the pathogenesis of sepsis. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 31(4), pp. 379-88. [DOI:10.1007/s10096-011-1337-4] [PMID]

Krinsley, J. S., et al., 2013. Diabetic status and the relation of the three domains of glycemic control to mortality in critically ill patients: an international multicenter cohort study. Critical Care, 17(2), pp. R37. [DOI:10.1186/cc12584] [PMID]

Kuperman, E. F., et al., 2013. The impact of obesity on sepsis mortality: A retrospective review. BMC Infectious Diseases, 16(13), pp. 377. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2334-13-377] [PMID]

Lanspa, M. J., et al., 2013. Moderate glucose control is associated with increased mortality compared with tight glucose control in critically ill patients without diabetes. Chest, 143(5), pp. 1226-34. [DOI:10.1378/chest.12-2072] [PMID]

Ledoux D., et al., 2008. SAPS 3 admission score: An external validation in a general intensive care population. Intensive Care Medicine, 34(10), pp. 1873-7. [DOI:10.1007/s00134-008-1187-4] [PMID]

Lee, A., et al., 2017. Are high nurse workload/staffing ratios associated with decreased survival in critically ill patients? A cohort study. Annals of Intensive Care, 7(46), pp. 46. [DOI:10.1186/s13613-017-0269-2] [PMID]

Li, X., et al., 2021. Prevalence of comorbidities and their associated factors in patients with type 2 diabetes at a tertiary care department in Ningbo, China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 11(1), pp. e040532. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040532] [PMID]

Mendez, C. E., et al., 20132. Increased glycemic variability is independently associated with length of stay and mortality in noncritically ill hospitalized patients. Diabetes Care, 36(12), pp. 4091-7. [DOI:10.2337/dc12-2430] [PMID]

Miranda, D. R., et al., 2003. Nursing activities score. Crit Care Medicine, 31(2), pp. 374-82. [DOI:10.1097/01.CCM.0000045567.78801.CC] [PMID]

Nassiff, A., et al., 2018. Nursing workload and patient mortality at an intensive care unit. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem, 27(4), pp. e0390017.

Padilha, K. G., et al., 2015. Nursing activities score: An updated guideline for its application in the intensive care unit. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 49, pp. 131-7. [DOI:10.1590/S0080-623420150000700019] [PMID]

Papadimitriou-Olivgeris, M., et al., 2016. The role of obesity in sepsis outcome among critically ill patients: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. BioMed Research International, 2016, pp. 5941279. [DOI:10.1155/2016/5941279] [PMID]

Petronilho, F., et al., 2016. Obesity exacerbates sepsis-induced oxidative damage in organs. Inflammation, 39(6), pp. 2062-71. [DOI:10.1007/s10753-016-0444-x] [PMID]

Poston, J. T. & Koyner J. L., 2019. Sepsis associated acute kidney injury. BMJ, 9(364), pp. k4891. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.k4891] [PMID]

Queijo, A. F. & Padilha, K. G., 2009, Nursing Activities Score (NAS): Cross-cultural adaptation and validation to Portuguese language. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 43, pp. 1018-25. [DOI:10.1590/S0080-62342009000500004]

Reinhart, K., et al., 2017. Recognizing sepsis as a global health priority - A WHO resolution. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(5), pp. 414-7. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMp1707170] [PMID]

Ross, P., et al., 2023. Nursing workload and patient-focused outcomes in intensive care: A systematic review. Nursing Health Science, 25(4), pp. 497-515. [DOI:10.1111/nhs.13052] [PMID]

Sakr, Y., et al., 2008. Sepsis and organ system failure are major determinants of post–intensive care unit mortality. Journal of Critical Care, 23(4), pp. 475-83. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.09.006] [PMID]

Sechterberger, M. K., et al., 2013. The effect of diabetes mellitus on the association between measures of glycaemic control and ICU mortality: A retrospective cohort study. Critical Care, 17(2), pp. R52. [DOI:10.1186/cc12572] [PMID]

Shorr, A. F., et al., 2014. Predictors of hospital mortality among septic ICU patients with Acinetobacter spp. bacteremia: A cohort study. BMC Infectious Diseases, 14, pp. 572. [DOI:10.1186/PREACCEPT-9162747951401206] [PMID]

Silveira, L. M., et al., 2017. Glycaemic variability in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock admitted to an intensive care unit. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 41, pp. 98-103. [DOI:10.1016/j.iccn.2017.01.004] [PMID]

Singer, M., et al., 2016. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA, 315(8), pp. 801-10. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.0287] [PMID]

Singh, G., et al., 2016. Risk factors for early invasive fungal disease in critically ill patients. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 20(11), pp. 633-9. [DOI:10.4103/0972-5229.194007] [PMID]

Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes., 2015. Posicionamento oficial SBD nº 03/2015: Controle da glicemia no paciente hospitalizado (32 p.). São Paulo, Brazil. Retrieved from: [Link]

Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes., 2019. Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes 2019-2020, São Paulo, Brazil: Clannad. Retrieved from: [Link]

Tiwari, S., et al., 2011. Sepsis in diabetes: A bad duo. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome, 5(4), pp. 222-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.dsx.2012.02.026] [PMID]

Torimoto, K., et al., 2013. Relationship between fluctuations in glucose levels measured by continuous glucose monitoring and vascular endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovascular Diabetology, 2(12), pp. 1. [DOI:10.1186/1475-2840-12-1] [PMID]

Van Vught, L. A., et al., 2017. Diabetes is not associated with increased 90-day mortality risk in critically ill patients with sepsis. Critical Care Medicine, 45(10), pp. e1026-35. [DOI:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002590] [PMID]

Van Vught, L. A., et al., 2016. Association of diabetes and diabetes treatment with the host response in critically ill sepsis patients. Critical Care, 20(1), pp. 252. [DOI:10.1186/s13054-016-1429-8] [PMID]

Venot, M., et al., 2015. Acute kidney injury in severe sepsis and septic shock in patients with and without diabetes mellitus: A multicenter study. PloS One, 10(5), pp. e0127411. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0127411] [PMID]

Vincent, J. L. et al., 1996. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis - Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive and Care Medicine, 22(7), pp. 707-10. [DOI:10.1007/BF01709751] [PMID]

Vieira, A. A., et al., 2015. Obesity promotes oxidative stress and exacerbates sepsis-induced brain damage. Current Neurovascular Research, 12(2), pp. 147-54. [DOI:10.2174/1567202612666150311111913] [PMID]

Wang, Z., et al., 2017. Association between diabetes mellitus and outcomes of patients with sepsis: A meta-analysis. Medical Science Monitor, 23, pp. 3546-55. [DOI:10.12659/MSM.903144] [PMID]

Yang, W. S., et al., 2020. The association between body mass index and the risk of hospitalization and mortality due to infection: A prospective cohort study. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 8(1), pp. ofaa545. [DOI:10.1093/ofid/ofaa545] [PMID]

Ying, C., et al., 2016. Blood glucose fluctuation accelerates renal injury involved to inhibit the AKT signaling pathway in diabetic rats. Endocrine, 53(1), pp. 81-96. [DOI:10.1007/s12020-016-0867-z] [PMID]

Zambonato, B. P., et al., 2013. Association of Braden subscales with the risk of development of pressure ulcers. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem, 34(1), pp. 21-8. [DOI:10.1590/S1983-14472013000200003] [PMID]

Ledoux D., et al., 2008. SAPS 3 admission score: An external validation in a general intensive care population. Intensive Care Medicine, 34(10), 1873-7. [DOI:10.1007/s00134-008-1187-4] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2025/02/19 | Accepted: 2025/08/17 | Published: 2026/02/1

Received: 2025/02/19 | Accepted: 2025/08/17 | Published: 2026/02/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |