Mon, Jan 5, 2026

[Archive]

Volume 5, Issue 4 (Autumn 2019)

JCCNC 2019, 5(4): 257-268 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hakimi R, Kheirkhah M, Abolghasemi J, Hakimi M. The Effect of Face-to-face Sex Education on the Sexual Function of Adolescent Female Afghan Immigrants. JCCNC 2019; 5 (4) :257-268

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-247-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-247-en.html

1- International Campus, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Nursing Care Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,kheirkhah.m@iums.ac.ir.

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Nursing Care Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 808 kb]

(1717 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4935 Views)

The required data were collected by a demographic form and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). The demographic sheet contained 23 questions, including the couple’s age, age at marriage, marriage duration, the couple’s occupational status, the couple’s educational level, the number of children, the number of pregnancies, the number of abortions, initial willingness for marriage, living with others except for children, having a private bedroom, economic status, the use of certain medications or substances to increase libido, their experience of sexual relationship, sexual satisfaction, foreplay by husband, sex initiator, contraception type, as well as the duration and frequency of sexual intercourse per month.

The FSFI is a 19-item inventory which evaluates female sexual performance in 6 domains of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain (Rosen et al. 2010). According to its instructions, because the number of questions in each domain is not similar, to calculate individual domain scores, the scores of the individual items that comprise the domain are added up, and the sum is multiplied by the domain factor. To obtain the total scale’s score, the scores of the 6 domains are added up, which ranges from 2-36. A higher overall score indicates a better sexual function with a cut-off point of 28 (Rosen et al. 2000). Fakhri et al. (2011) evaluated the reliability of the Persian version of the FSFI and reported a correlation coefficient of 0.42 for desire, 0.56 for arousal, 0.65 for lubrication, 0.68 for orgasm, 0.72 for satisfaction, 0.30 for pain, and 0.54 for the total score (Fakhri et al. 2011). In the present study, the test-retest method was applied to assess the reliability of the tool. Twenty subjects, who were not included in the survey, were requested to complete the questionnaire at a two-week interval. After data collection, a test-retest-reliability coefficient of 0.86, 0.82, 0.86, 0.80, 0.91, 0.88, and 0.87 was obtained for the subscales of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, pain, and total sexual function score, respectively.

After receiving ethical permission, an introduction letter was issued by Iran University of Medical Sciences, which was presented to Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. Then, two charity centers in two different regions of the city with the largest number of female Afghan visitors were selected. These centers provided services on various topics, such as first aid, basic reading and writing skills, English language, sewing, Quran learning, child-rearing, etc. to immigrants. These services were provided in the form of educational workshops and classes at meager costs, or sometimes free of charge.

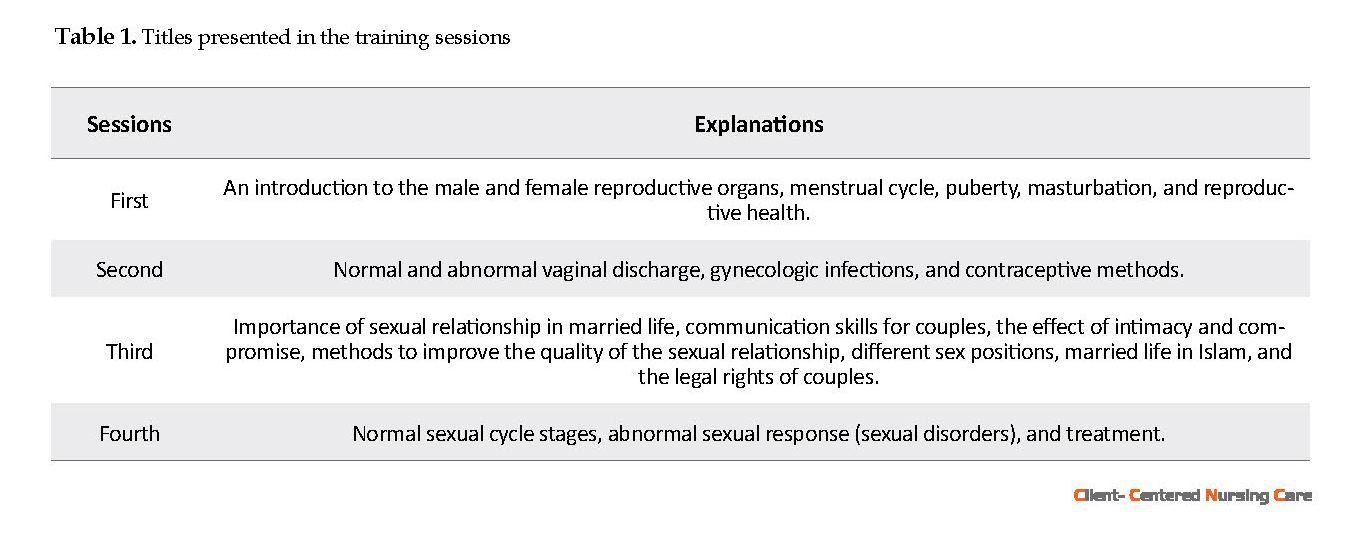

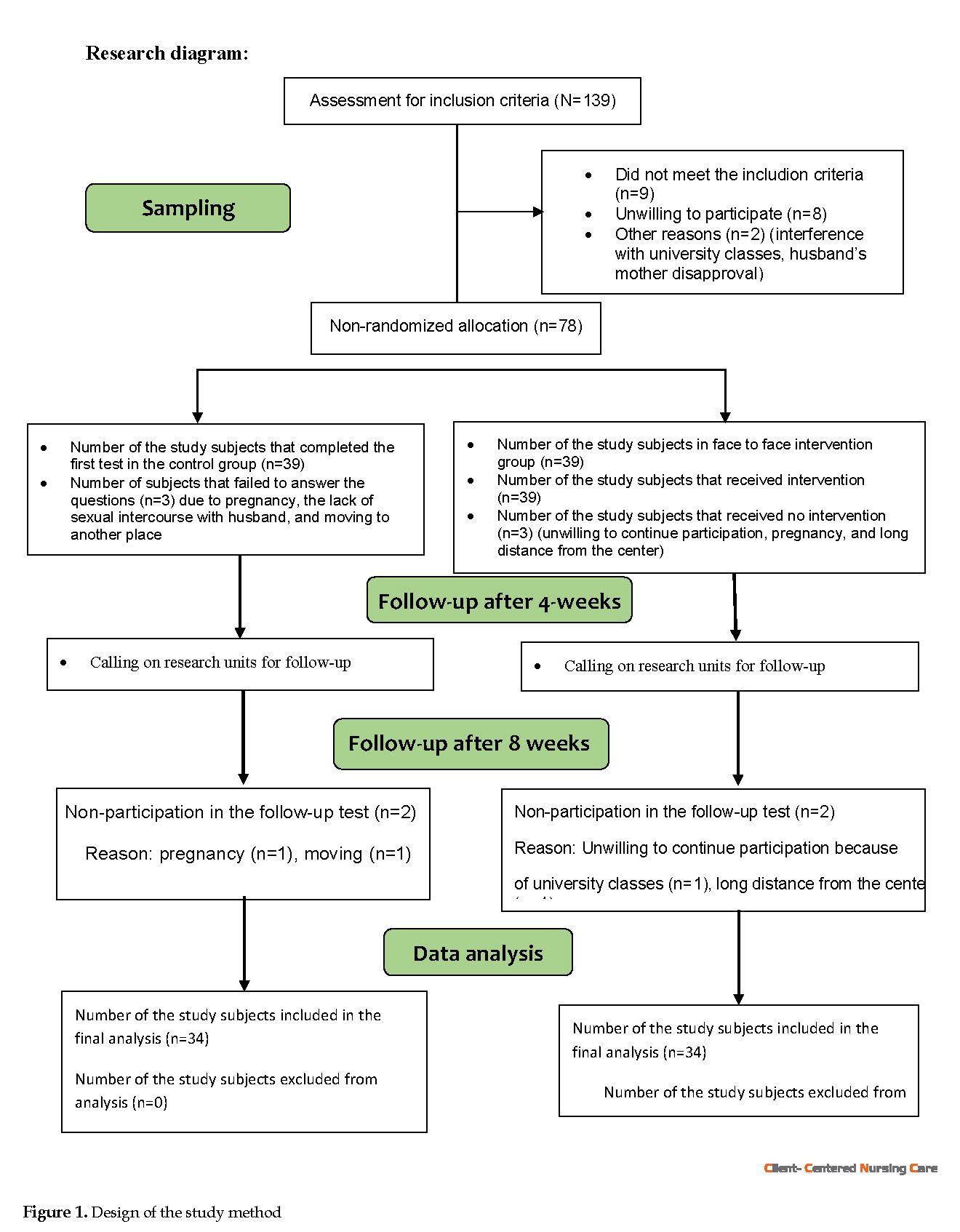

One center was randomly selected as the case center. The eligible subjects that met the inclusion criteria were enrolled, and informed consent was obtained from them after explaining the study objectives. Then, they completed the demographic questionnaire and FSFI. In addition to routine programs of the center, the case group subjects received 4 weekly training sessions for 4 consecutive weeks. The educational content was reviewed and approved by 5 faculty members of Iran University of Medical Sciences. Furthermore, the training was provided by the researcher (Master of Midwifery Student) in 60- to 90-minute sessions. The training was conducted face-to-face using lectures, as well as questions and answers. Slides were also used as teaching aids. At the end of the last session, the study participants’ questions were answered. The content presented in the intervention sessions is presented in Table 1.

Finally, the FSFI was completed by all the study subjects. To evaluate the durability of this educational method, the study participants were contacted via phone to attend the center and complete the questionnaires after 8 weeks. The control group only received routine programs at the charity center. To encourage attendance, the study subjects in both groups received a free-of-charge breast examination. At the end of the study, the relevant CDs were also provided to the control group.

Of 78 participants (39 in the control group and 39 in the case group), 6 and 4 were excluded during and at the end of the study, respectively. Three study subjects were excluded from the control group due to pregnancy, the lack of sexual intercourse with their husband, and moving to another house. In the case group, 3 study subjects were excluded due to unwillingness to continue participating in the study, pregnancy, and long distance from the center. The data of 68 subjects, 34 per group, were eventually analyzed.

The obtained data were analyzed using SPSS. Descriptive statistics, such as frequency distribution tables, numerical indicators, and inferential statistics, such as Chi-squared test, Independent Samples t-test, Paired Samples t-test, one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), repeated-measures ANOVA, and Bonferroni post-hoc test were applied for data analysis (Figure 1).

3. Results

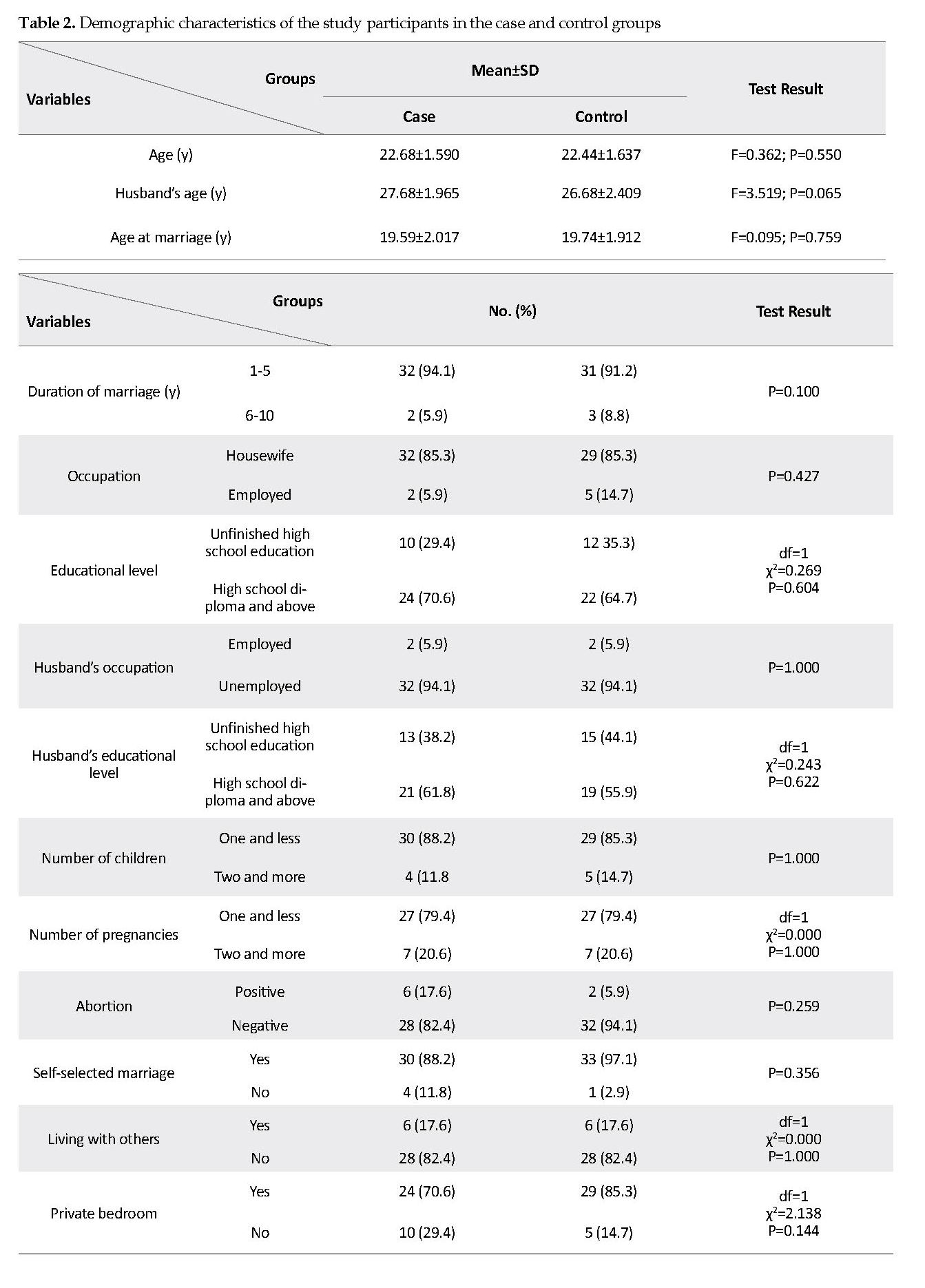

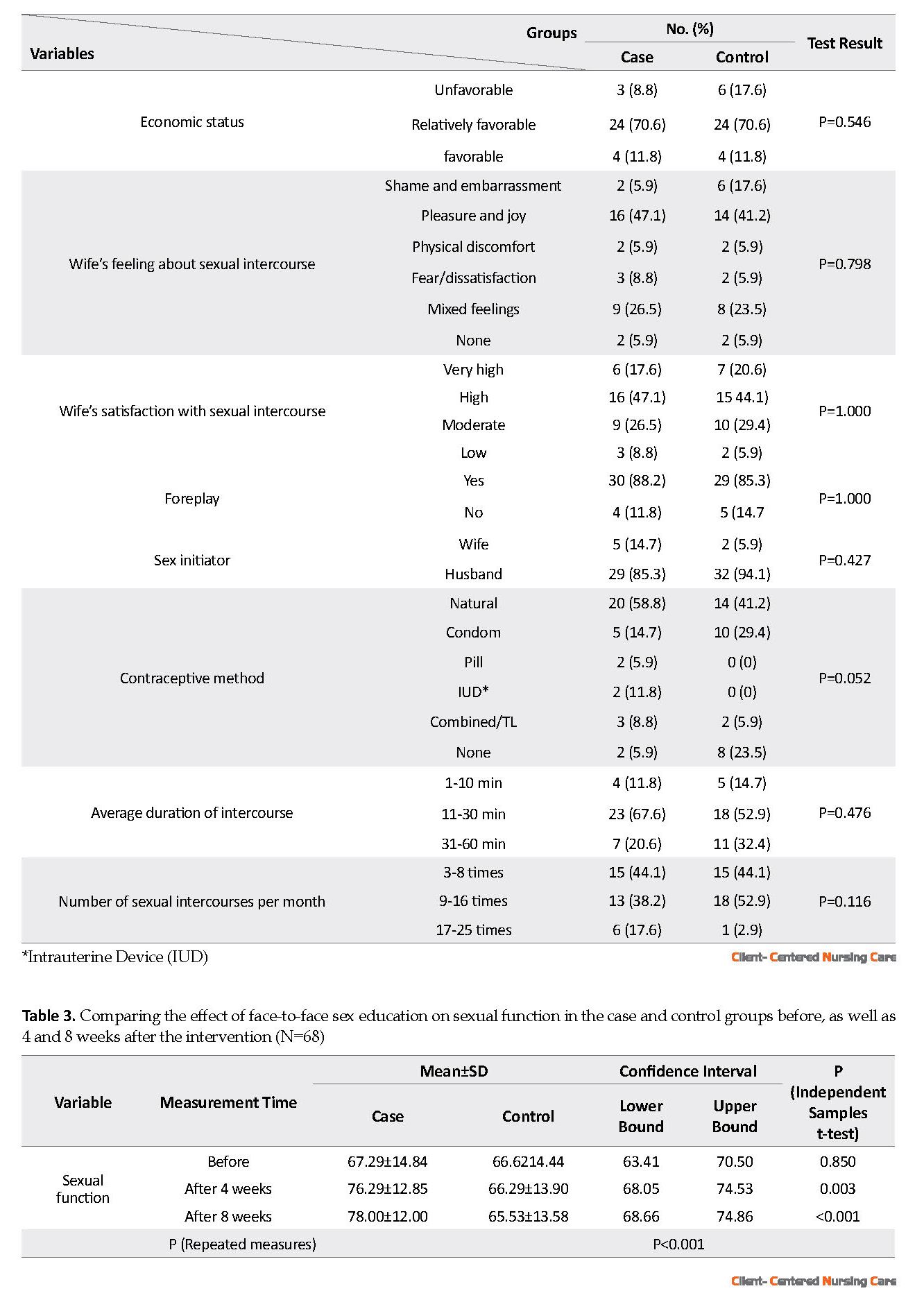

There was no significant difference between the demographic characteristics of the study groups. Table 2 presents the demographic characteristics of the study participants.

4. Discussion

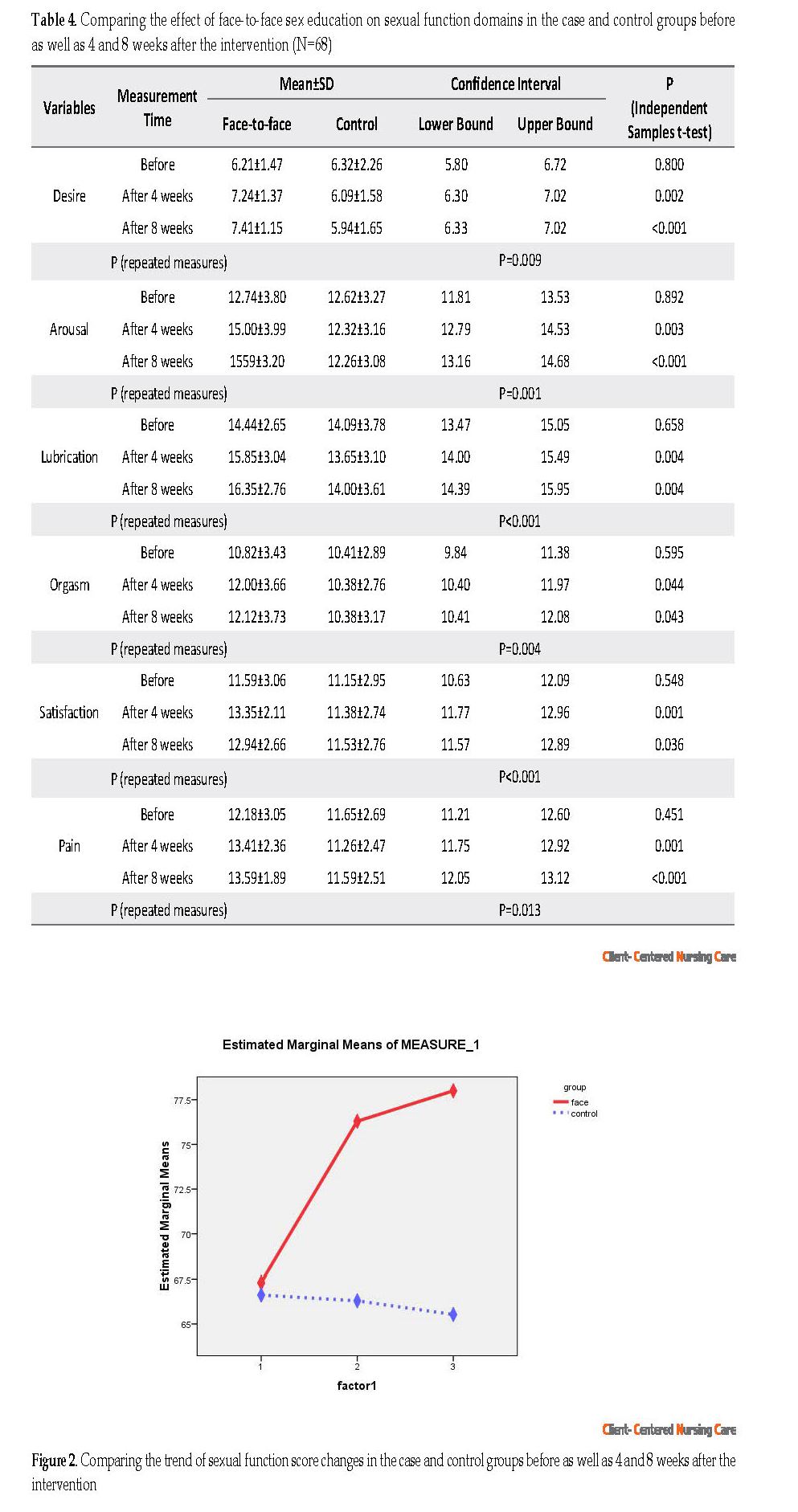

According to the present study data, providing face-to-face sex education has improved sexual function scores and all its components in the investigated Afghan immigrant adolescent women. There was no significant difference in the mean score of sexual function in the two groups before the intervention. In contrast, significant differences were observed 4 weeks and 8 weeks after the intervention in the test group. Moreover, the difference in the values of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain was also significant between the study groups (Figure 2, 3 & 4). Providing the sexual content alongside the young age of the participants, the use of a fellow teacher to reduce misunderstanding and the possibility of discussion among study participants were among the possible causes of the success of this program among the studied immigrants.

● Most marriages of immigrants living in Iran occur during adolescence.

● Unawareness about sexual and marital issues could adversely affect marital relationships.

● Women’s ignorance of various aspects of sexual issues could lead to unsuccessful sexual relationships and undesirable sexual function.

● Sexual education could increase awareness and consequently improve sexual function.

Plain Language Summary

The current study assessed the effect of face-to-face sex education on the sexual function of adolescent female Afghan immigrants in the selected charity centers of the immigrant areas of Mashhad City, Iran. Obtaining accurate, documented, and credible information on sexual issues could prevent undesirable sexual function. This information, in the form of sex education, helps couples to gain the necessary knowledge to satisfy each other’s sexual needs. This study reported that providing face-to-face sexual training has improved the sexual function of adolescent female Afghan migrants; therefore, this training method could be used for sexual education in young female immigrants.

● Unawareness about sexual and marital issues could adversely affect marital relationships.

● Women’s ignorance of various aspects of sexual issues could lead to unsuccessful sexual relationships and undesirable sexual function.

● Sexual education could increase awareness and consequently improve sexual function.

Plain Language Summary

The current study assessed the effect of face-to-face sex education on the sexual function of adolescent female Afghan immigrants in the selected charity centers of the immigrant areas of Mashhad City, Iran. Obtaining accurate, documented, and credible information on sexual issues could prevent undesirable sexual function. This information, in the form of sex education, helps couples to gain the necessary knowledge to satisfy each other’s sexual needs. This study reported that providing face-to-face sexual training has improved the sexual function of adolescent female Afghan migrants; therefore, this training method could be used for sexual education in young female immigrants.

Full-Text: (1423 Views)

1. Introduction

Adolescence is associated with sexual maturity (Tulloch & Kaufman 2013). Moreover, improper parent-adolescent relationships complicate understanding how to behave and manage the sexual needs of this age group (Refaie Shirpak et al. 2007). A total of 979, 400 Afghan, and Iraqi live in Iran (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee 2019). Iran and Afghanistan, like other countries of the South Asian region, have the first rank of marriage in adolescents (UNICEF 2014; UNFPA 2012). Marriage, at this age, has deep cultural roots and is sometimes due to the low socioeconomic status of the girl’s family (Central Statistics Organization 2018; Hadi 2016).

Sexual disorders and the inability to have a healthy and enjoyable relationship could results in widespread biopsychosocial consequences (Shakerian et al. 2014; Tavakol et al. 2012; Ziaee et al. 2014b). Having a satisfying sexual relationship plays a vital role in keeping the family together (Mohammadsadeg et al. 2018). Sexual ignorance is among the factors affecting incompatibility and, consequently, dissatisfaction in relationships (Sadri Damirchi et al. 2016). Lack of knowledge and access to information resources due to religious taboos and cultural norms have led to increased levels of obtaining information from unscientific resources; such issue not only has led to couples’ dissatisfaction but also has caused problems in their relationships (Refaie Shirpak et al. 2007). Education in this area plays a key role in family health (WHO 2014); therefore, providing sexual education to women could be effective (Jahanfar & Molaie Nejad 2013). The importance of this training is especially critical in developing countries because they have limited information services and low access to sexual and reproductive health resources (Hindin & Fatusi 2009). The quality of sexual training and the level of information about these issues vary in different regions depending on the cultural norms.

Despite all cultural developments in training sexual information in families, the culture of societies is still a major obstacle in this regard (Abedini et al. 2016). Within the context of Afghan society, discussing sexual matters is forbidden in families and communities, and this prohibition is observed in disciplining their children (Hadi 2016). Although Afghan immigrants and Iranian citizens are living in similar environments, they have different beliefs and behaviors. As ethnicity affects individuals’ sexual performance (Hosain et al. 2013), there is a need to develop a specific educational program for Afghan immigrants, considering cultural sensitivities. To ensure the success of these programs, it is required to follow the religious context of Islamic societies (Refaie Shirpak et al. 2007).

Sex education is among the top priorities of women’s health (UNICEF 2018). It can lead to improved attitudes and learning special skills needed for everyone to prevent sexual problems (Mahmoudi et al. 2007; TalaiZadeh & Bakhtiyarpour 2016). Fostering a positive attitude on sexuality is inadequate for having a proper sexual function; inappropriate information sources and insufficient information also aggravate such conditions (Refaie Shirpak et al. 2007). There are various instructional strategies that educators can use to improve learner’s knowledge to provide high-quality education (Xu 2016).

Face-to-face training provision is common in the healthcare system. This is a conventional educational approach in the healthcare system, i.e., used along with other methods of education, such as group discussion and presenting educational pamphlets (Karimi Moonaghi et al. 2012; Sargazi et al. 2014). In addition to increased knowledge (Mohammadshahi et al. 2014) and higher levels of awareness in learners (Sharifi, Feyzi & Arteshehdar 2013), this educational method leads to more satisfaction and a positive understanding of the learning process (Ortega-Maldonado et al. 2017). Considering the importance of sex education and its effect on couples’ relationships, this study aimed to determine the effect of face-to-face education on the sexual function of adolescent female Afghan immigrants.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a quasi-experimental with a Pre-test-Post-test and a control group design. This research was conducted in two immigrant neighborhoods of Mashhad City, Iran (Kheir-ol-Bashar Telgerd and Saheb-al-Zaman Golshar). Two charity centers with the largest numbers of Afghan immigrants were selected through purposive sampling technique. One of them was randomly selected as the case center and the other as the control center.

Young Afghan females aged 10-24 years who could communicate in Farsi (reading and writing), were married officially, were the only wives of their husbands, were married for at least one year, had not received official sex education in the past, lacked medical diseases (diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, renal & hepatic diseases), were not dependent on opium and psychedelics (including their husbands), and had not experienced stressful events (death of a child or a first-degree relative, a severe disease of a close relative, imprisonment of a family member, depression, etc.) in the past 6 months, were not pregnant or lactating, did not experience an abortion in the past three months, lived with their husband, and had sexual intercourse with their husband were included in this study (Alimohammadi et al. 2018; Behboodi Moghadam et al. 2015; Yousefzadeh et al. 2017; Kheyrkhah et al. 2014 ).

The exclusion criteria were pregnancy during the study, the lack of sexual intercourse with the husband for any reason during the study, the occurrence of stressful events during the study, withdrawal from the study, as well as missing the third and fourth educational sessions. Eligible subjects were enrolled from October 7 to November 6, 2018. Then, they were assigned to the case and control groups according to the charity center they presented to.

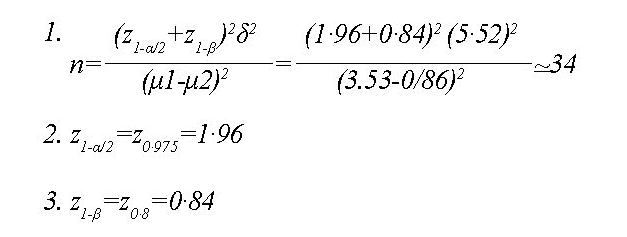

The calculated sample size was 38 subjects per group considering a confidence interval of 95%, power of 80%, and standard deviation (σ) of 5.52, considering the previous studies (Behboodi Moghadam et al. 2015), and an attrition rate of 10% using the following Formula 1, 2 & 3:

Adolescence is associated with sexual maturity (Tulloch & Kaufman 2013). Moreover, improper parent-adolescent relationships complicate understanding how to behave and manage the sexual needs of this age group (Refaie Shirpak et al. 2007). A total of 979, 400 Afghan, and Iraqi live in Iran (Khodabakhshi-Koolaee 2019). Iran and Afghanistan, like other countries of the South Asian region, have the first rank of marriage in adolescents (UNICEF 2014; UNFPA 2012). Marriage, at this age, has deep cultural roots and is sometimes due to the low socioeconomic status of the girl’s family (Central Statistics Organization 2018; Hadi 2016).

Sexual disorders and the inability to have a healthy and enjoyable relationship could results in widespread biopsychosocial consequences (Shakerian et al. 2014; Tavakol et al. 2012; Ziaee et al. 2014b). Having a satisfying sexual relationship plays a vital role in keeping the family together (Mohammadsadeg et al. 2018). Sexual ignorance is among the factors affecting incompatibility and, consequently, dissatisfaction in relationships (Sadri Damirchi et al. 2016). Lack of knowledge and access to information resources due to religious taboos and cultural norms have led to increased levels of obtaining information from unscientific resources; such issue not only has led to couples’ dissatisfaction but also has caused problems in their relationships (Refaie Shirpak et al. 2007). Education in this area plays a key role in family health (WHO 2014); therefore, providing sexual education to women could be effective (Jahanfar & Molaie Nejad 2013). The importance of this training is especially critical in developing countries because they have limited information services and low access to sexual and reproductive health resources (Hindin & Fatusi 2009). The quality of sexual training and the level of information about these issues vary in different regions depending on the cultural norms.

Despite all cultural developments in training sexual information in families, the culture of societies is still a major obstacle in this regard (Abedini et al. 2016). Within the context of Afghan society, discussing sexual matters is forbidden in families and communities, and this prohibition is observed in disciplining their children (Hadi 2016). Although Afghan immigrants and Iranian citizens are living in similar environments, they have different beliefs and behaviors. As ethnicity affects individuals’ sexual performance (Hosain et al. 2013), there is a need to develop a specific educational program for Afghan immigrants, considering cultural sensitivities. To ensure the success of these programs, it is required to follow the religious context of Islamic societies (Refaie Shirpak et al. 2007).

Sex education is among the top priorities of women’s health (UNICEF 2018). It can lead to improved attitudes and learning special skills needed for everyone to prevent sexual problems (Mahmoudi et al. 2007; TalaiZadeh & Bakhtiyarpour 2016). Fostering a positive attitude on sexuality is inadequate for having a proper sexual function; inappropriate information sources and insufficient information also aggravate such conditions (Refaie Shirpak et al. 2007). There are various instructional strategies that educators can use to improve learner’s knowledge to provide high-quality education (Xu 2016).

Face-to-face training provision is common in the healthcare system. This is a conventional educational approach in the healthcare system, i.e., used along with other methods of education, such as group discussion and presenting educational pamphlets (Karimi Moonaghi et al. 2012; Sargazi et al. 2014). In addition to increased knowledge (Mohammadshahi et al. 2014) and higher levels of awareness in learners (Sharifi, Feyzi & Arteshehdar 2013), this educational method leads to more satisfaction and a positive understanding of the learning process (Ortega-Maldonado et al. 2017). Considering the importance of sex education and its effect on couples’ relationships, this study aimed to determine the effect of face-to-face education on the sexual function of adolescent female Afghan immigrants.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a quasi-experimental with a Pre-test-Post-test and a control group design. This research was conducted in two immigrant neighborhoods of Mashhad City, Iran (Kheir-ol-Bashar Telgerd and Saheb-al-Zaman Golshar). Two charity centers with the largest numbers of Afghan immigrants were selected through purposive sampling technique. One of them was randomly selected as the case center and the other as the control center.

Young Afghan females aged 10-24 years who could communicate in Farsi (reading and writing), were married officially, were the only wives of their husbands, were married for at least one year, had not received official sex education in the past, lacked medical diseases (diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, renal & hepatic diseases), were not dependent on opium and psychedelics (including their husbands), and had not experienced stressful events (death of a child or a first-degree relative, a severe disease of a close relative, imprisonment of a family member, depression, etc.) in the past 6 months, were not pregnant or lactating, did not experience an abortion in the past three months, lived with their husband, and had sexual intercourse with their husband were included in this study (Alimohammadi et al. 2018; Behboodi Moghadam et al. 2015; Yousefzadeh et al. 2017; Kheyrkhah et al. 2014 ).

The exclusion criteria were pregnancy during the study, the lack of sexual intercourse with the husband for any reason during the study, the occurrence of stressful events during the study, withdrawal from the study, as well as missing the third and fourth educational sessions. Eligible subjects were enrolled from October 7 to November 6, 2018. Then, they were assigned to the case and control groups according to the charity center they presented to.

The calculated sample size was 38 subjects per group considering a confidence interval of 95%, power of 80%, and standard deviation (σ) of 5.52, considering the previous studies (Behboodi Moghadam et al. 2015), and an attrition rate of 10% using the following Formula 1, 2 & 3:

The required data were collected by a demographic form and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). The demographic sheet contained 23 questions, including the couple’s age, age at marriage, marriage duration, the couple’s occupational status, the couple’s educational level, the number of children, the number of pregnancies, the number of abortions, initial willingness for marriage, living with others except for children, having a private bedroom, economic status, the use of certain medications or substances to increase libido, their experience of sexual relationship, sexual satisfaction, foreplay by husband, sex initiator, contraception type, as well as the duration and frequency of sexual intercourse per month.

The FSFI is a 19-item inventory which evaluates female sexual performance in 6 domains of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain (Rosen et al. 2010). According to its instructions, because the number of questions in each domain is not similar, to calculate individual domain scores, the scores of the individual items that comprise the domain are added up, and the sum is multiplied by the domain factor. To obtain the total scale’s score, the scores of the 6 domains are added up, which ranges from 2-36. A higher overall score indicates a better sexual function with a cut-off point of 28 (Rosen et al. 2000). Fakhri et al. (2011) evaluated the reliability of the Persian version of the FSFI and reported a correlation coefficient of 0.42 for desire, 0.56 for arousal, 0.65 for lubrication, 0.68 for orgasm, 0.72 for satisfaction, 0.30 for pain, and 0.54 for the total score (Fakhri et al. 2011). In the present study, the test-retest method was applied to assess the reliability of the tool. Twenty subjects, who were not included in the survey, were requested to complete the questionnaire at a two-week interval. After data collection, a test-retest-reliability coefficient of 0.86, 0.82, 0.86, 0.80, 0.91, 0.88, and 0.87 was obtained for the subscales of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, pain, and total sexual function score, respectively.

After receiving ethical permission, an introduction letter was issued by Iran University of Medical Sciences, which was presented to Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. Then, two charity centers in two different regions of the city with the largest number of female Afghan visitors were selected. These centers provided services on various topics, such as first aid, basic reading and writing skills, English language, sewing, Quran learning, child-rearing, etc. to immigrants. These services were provided in the form of educational workshops and classes at meager costs, or sometimes free of charge.

One center was randomly selected as the case center. The eligible subjects that met the inclusion criteria were enrolled, and informed consent was obtained from them after explaining the study objectives. Then, they completed the demographic questionnaire and FSFI. In addition to routine programs of the center, the case group subjects received 4 weekly training sessions for 4 consecutive weeks. The educational content was reviewed and approved by 5 faculty members of Iran University of Medical Sciences. Furthermore, the training was provided by the researcher (Master of Midwifery Student) in 60- to 90-minute sessions. The training was conducted face-to-face using lectures, as well as questions and answers. Slides were also used as teaching aids. At the end of the last session, the study participants’ questions were answered. The content presented in the intervention sessions is presented in Table 1.

Finally, the FSFI was completed by all the study subjects. To evaluate the durability of this educational method, the study participants were contacted via phone to attend the center and complete the questionnaires after 8 weeks. The control group only received routine programs at the charity center. To encourage attendance, the study subjects in both groups received a free-of-charge breast examination. At the end of the study, the relevant CDs were also provided to the control group.

Of 78 participants (39 in the control group and 39 in the case group), 6 and 4 were excluded during and at the end of the study, respectively. Three study subjects were excluded from the control group due to pregnancy, the lack of sexual intercourse with their husband, and moving to another house. In the case group, 3 study subjects were excluded due to unwillingness to continue participating in the study, pregnancy, and long distance from the center. The data of 68 subjects, 34 per group, were eventually analyzed.

The obtained data were analyzed using SPSS. Descriptive statistics, such as frequency distribution tables, numerical indicators, and inferential statistics, such as Chi-squared test, Independent Samples t-test, Paired Samples t-test, one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), repeated-measures ANOVA, and Bonferroni post-hoc test were applied for data analysis (Figure 1).

3. Results

There was no significant difference between the demographic characteristics of the study groups. Table 2 presents the demographic characteristics of the study participants.

4. Discussion

According to the present study data, providing face-to-face sex education has improved sexual function scores and all its components in the investigated Afghan immigrant adolescent women. There was no significant difference in the mean score of sexual function in the two groups before the intervention. In contrast, significant differences were observed 4 weeks and 8 weeks after the intervention in the test group. Moreover, the difference in the values of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain was also significant between the study groups (Figure 2, 3 & 4). Providing the sexual content alongside the young age of the participants, the use of a fellow teacher to reduce misunderstanding and the possibility of discussion among study participants were among the possible causes of the success of this program among the studied immigrants.

The current study's findings were consistent with those of another study that investigated the effect of sexual training on women with sexual dysfunction. In this study, like ours, the total scores of study participants’ sexual performance significantly increased after receiving sex training. It also affected the components of sexual desire, sexual arousal, lubrication, and satisfaction; however, contrary to our study, it had no effect on orgasm and sexual pain (Behboodi Moghadam et al. 2015). The inconsistency between these two studies in the components of pain and orgasm could be due to incongruences between the age of the samples and the time of their marriage. Moreover, the prolonged time post marriage could affect the studied samples’ orgasm status (Mazinani et al. 2013).

According to a study on married female students at Ferdows University in Mashhad City, Iran, sex skills training can create a significant difference in the sexual function and components of sexual desire, arousal, vaginal moisture, orgasm, and satisfaction (Ziaee, Sepehri Shamlou & Mashhadi 2014a). This study was relatively consistent with the present study. Besides, the inconsistency in pain components may be due to differences in the level of education and the culture of the study participants (Khaki Rostami et al. 2015). Another study on 18- to 44-year-old women suggested improved scores of sexual desire after the training (Kaviani et al. 2014), i.e. in line with the results of this study. Another research was conducted in Mashhad to determine the effect of educational packages on the sexual function of pregnant women in childbearing age.

According to a study on married female students at Ferdows University in Mashhad City, Iran, sex skills training can create a significant difference in the sexual function and components of sexual desire, arousal, vaginal moisture, orgasm, and satisfaction (Ziaee, Sepehri Shamlou & Mashhadi 2014a). This study was relatively consistent with the present study. Besides, the inconsistency in pain components may be due to differences in the level of education and the culture of the study participants (Khaki Rostami et al. 2015). Another study on 18- to 44-year-old women suggested improved scores of sexual desire after the training (Kaviani et al. 2014), i.e. in line with the results of this study. Another research was conducted in Mashhad to determine the effect of educational packages on the sexual function of pregnant women in childbearing age.

Accordingly, the data suggested that providing sexual function package could change sexual desire dimensions, sexual excitement, the lubrication of the vagina, orgasm, sexual satisfaction, sexual pain, and overall sexual function score (Baradaran-Akbarzadeh et al., 2018). This result is in line with that of our study. The findings of another study are to some extent consistent with ours; however, there was an inconsistency in the components of arousal, vaginal lubrication, orgasm, and sexual pain, which may be due to differences in the age and marital status of the study groups (Yousefzadeh et al. 2017). These factors affect sexual dysfunction (Mazinani et al. 2013). The mean age and the duration of the marriage were 33 and 13 years, respectively, in their studied samples, while the same figures in our study were 22 and 5 years, respectively.

A study revealed that intervention provision had modified the scores of the components of sexual desire, sexual arousal, lubrication, satisfaction, and the total score of sexual function (Brotto & Basson 2014) (Table 4). Teaching topics, such as communication and communication skills in this intervention has focused on the role of psychological factors, and this may have led to consistency between two studies; no change in pain and orgasm components in Brotto and Bassoon’s research may be associated with the older age of the explored subjects and cultural differences between the selected intervention groups. The issue of gender, especially among the Afghan population, is considered as a taboo. Additionally, considering the socio-cultural, religious, and political beliefs in Islamic societies, it is recommended that training sessions be held in migrant areas. Future studies are recommended to establish sex education classes in other immigrant areas with higher sample sizes and by implementing other educational methods and comparing the relevant results with the present study.

Applying the face-to-face sex training approach improved the sexual function of Afghan adolescents. Thus, this method can be used in the sex education of adolescent couples.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC1397.027) and registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (Code: IRCT20180611040054N1). The study was conducted after obtaining approval from Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (Approval Number: 97/32620). An informed consent form was obtained from the study subjects after explaining to them the objectives of the study.

Funding

This study was part of the MSc thesis of Razia Hakimi in Midwifery performed in the International Campus of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS) and financially supported by the UNFPA and Italian Embassy.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in designing, running, and writing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Vice-Chancellors for International Affairs and Research and Technology of IUMS, Salsal Animation Center, all study subjects who participated in the study, UNFPA, Italian Embassy, and Kheir-ol-Bashar and Saheb-al-Zamanan charity centers in Mashhad.

References

Abedini, E., et al. 2016. A qualitative study on mothers’ experience from sex education to female adolescents underlining culture factors. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health, 18(4), pp. 202-11. http://eprints.mums.ac.ir/1925/

Central Statistics Organization., 2018. Afghanistan living conditions survey 2016-17 [Internet]. Cited 6 June 2020, https://www.ilo.org/surveyLib/index.php/catalog/2114/download/17907

Alimohammadi, L., et al. 2018. The effectiveness of group counseling based on bandura’s self-efficacy theory on sexual function and sexual satisfaction in Iranian newlywed women: a randomized controlled trial. Applied Nursing Research, 42, pp. 62-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.apnr.2018.06.011] [PMID]

Baradaran-Akbarzadeh, N., et al. 2018. The effect of educational package on sexual function in cold temperament women of reproductive age. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 7, p. 65. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_7_18] [PMID] [PMCID]

Behboodi Moghadam, Z., et al. 2015. The effect of sexual health education program on women sexual function in Iran. Journal of Research in Health Sciences, 15(2), pp. 124-8. [PMID]

Brotto, L. A. & Basson, R., 2014. Group mindfulness-based therapy significantly improves sexual desire in women. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, pp. 43-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.001] [PMID]

Fakhri, A., et al 2011. Psychometric properties of iranian version of female sexual function index. Jundishapur Scientific Medical Journal 10(4), pp. 345-54. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=208887

Hadi, M. 2016. An analysis of policy and social factors impacting the uptake of sexual and reproductive health services in Kabul, Afghanistan [PhD. thesis]. Durham: University of Durham. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11862/

Hindin, M. J. & Fatusi, A. O., 2009. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing countries: An overview of trends and interventions. International perspectives on sexual and reproductive health, 35(2), pp. 58-62. [DOI:10.1363/3505809] [PMID]

Hosain, G. M., et al. 2013. Racial differences in sexual dysfunction among postdeployed Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. American Journal of Men’s Health, 7(5), pp. 374-81. [DOI:10.1177/1557988312471842] [PMID] [PMCID]

Jahanfar, S. & Molaie Nejad, M., 2013. Sexual dysfunction syllabus. Tehran: Jame-e-Negar Publishing House. http://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/bibliographic/3397039

Karimi MoonaghI, H., et al. 2012. A comparison of face-to-face and video-based education on attitude related to diet and fluids: Adherence in hemodialysis patients. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 17(5), pp. 360-4. [PMID] [PMCID]

Kaviani, M., et al. 2014. The effect of education on sexual health of women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Community based Nursing and Midwifery, 2(2), pp. 94-102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4201195/

Khaki Rostami, Z., et al. 2015. Sexual dysfunction and help seeking behaviors in newly married women in Sari, Iran: A cross-sectional study. Payesh, 14(6), pp. 677-86. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=465777

Kheyrkhah, M., Vahedi, M. & Jenani, P., 2014. The effect of group counselling on infrtility adjustment of infertile women in Tabriz Al-Zahra clinic. Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility, 17(113), pp. 7-14. http://eprints.mums.ac.ir/4230/

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Akhalaghi-Yazdi, R. & Hojati Sayah, M. Investigating gestalt-based play therapy on anxietyand loneliness in female children labour with sexual abuse: A Single Case Research Design (SCRD), 2019. Journal of Client-Centered Nursing Care, 5(3), pp. 147-56. [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.5.3.147]

Mahmoudi, G., Hasanzadeh, R. & Niazi Azar, K., 2007. [The effect of sex education on family health on Mazandaran medical university students (Persian)]. The Horizon of Medeical Science, 13(2), pp. 64-70. http://hms.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-168-en.html

Mazinani, R., et al. 2013. [Evaluation of prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and its related factors in women (Persian)]. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences, 19(105), pp. 59-66. http://rjms.iums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=2402&sid=1&slc_lang=en

Mohammadsadeg, A., Kalantar-Kosheh, S. M. & Naeimi, E., 2018. [The Experience of sexual problems in women seeking divorce and women satisfied with their marriage: A qualitative study(Persian)]. Journal of Qualtative Research in Health Sciences, 7(1), pp. 35-47. http://jqr.kmu.ac.ir/article-1-634-en.html

Mohammadshahi, M., et al. 2014. Comparing two different teaching methods: Traditional and teblog-based teaching (wbt) by group discussion. Educational Development of Jundishapur, 5(2), pp. 157-64. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=428708

Ortega-Maldonado, A., et al. 2017. Face-to-Face vs On-line: An analysis of profile, learning, performance and satisfaction among post graduate students. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 5(10), pp. 1701-6. [DOI:10.13189/ujer.2017.051005]

Refaie Shirpak, K., et al. 2007. Developing and testing a sex education program for the female clients of health centers in Iran. Sex Education, 7(4), pp. 333-49. [DOI:10.1080/14681810701636044]

Rosen, R., et al. 2000. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26(2), pp. 191-208. [DOI:10.1080/009262300278597] [PMID]

Sadri Damirchi, E., Poorzor, P. & Esmaili Ghazivaloii, F., 2016. [Effectiveness of sexual skills education on sexual attitude and knowledge in married women (Persian)]. Journal of Family Counseling & Psychotherapy, 6(1), pp. 1-15. http://fcp.uok.ac.ir/article_42720_en.html

Sargazi, M., et al. 2014. Effect of an Educational Intervention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior on behaviors leading to early diagnosis of Breast Cancer among women referred to health care centers in Zahedan in 2013. Iranian Quarterly Journal of Breast Diseases, 7(2), pp. 45-55. http://ijbd.ir/article-1-342-en.html

Shakerian, A., et al. 2014. Inspecting the relationship between sexual satisfaction and marital problems of divorce-asking women in sanandaj city family courts. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, pp. 327-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.706]

Sharifi, F., Feyzi, A. & Arteshehdar, E., 2013. [Knowledge and satisfaction of medical students with two methods of education for endocrine pathophysiology course: E-learning and lecture in classroom (Persian)]. Journal of Medical Education Development, 6(11), pp. 30-40. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=408326

Talaizadeh, F. & Bakhtiyarpour, S., 2016. [The relationship between marital satisfaction and sexual satisfaction with couple mental health (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology Andisheh va Raftar, 11(40), pp. 37-46. https://jtbcp.riau.ac.ir/article_939_en.html

Tavakol, Z., et al. 2012. [The relationship between sexual function and sexual satisfaction in women referring to centers sanitary health south of Tehran (Persian)]. Avicenna Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Care (Scientific Journal of Hamadan Nursing & Midwifery Faculty), 19(2), pp. 50-4. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=264138

Tulloch, T. & Kaufman, M., 2013. Adolescent sexuality. Pediatrics in Review, 34(1), pp. 29-38. [DOI:10.1542/pir.34-1-29] [PMID]

UNFPA., 2012. Marrying too young: End child marriage [Internet]. Cited 6 June 2020, https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/MarryingTooYoung.pdf [Accessed 5 March 2019].

UNICEF., 2014. Ending child marriage progress and prospects [Internet]. Cited 6 June 2020, https://www.unicef.org/media/files/Child_Marriage_Report_7_17_LR..pdf

UNICEF., 2018. Child marriage latest trends and future prospects [Internet]. Cited 6 June 2020, https://data.unicef.org/resources/child-marriage-latest-trends-and-future-prospects/

WHO., 2014. Health for the World’s Adolescents [Internet]. Cited 6 June 2020, http://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/files/1612_MNCAH_HWA_Executive_Summary.pdf [Accessed 4 March 2019].

XU, J. H., 2016. Toolbox of teaching strategies in nurse education. Chinese Nursing Research, 3(2), pp. 54-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.cnre.2016.06.002]

Yousefzadeh, S., Golmakani, N. & Nameni, F., 2017. The comparison of sex education with and without religious thoughts in sexual function of married women. Journal of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, 5(2), pp. 904-10. http://jmrh.mums.ac.ir/article_8384.html

Ziaee, P., Sepehri Shamlou, Z. & Mashhadi, A., 2014. The effectiveness of sexual education focused on cognitive schemas, on the improvement of sexual functioning among female married students. Evidence Based Care Journal, 4(2), pp. 73-82. http://ebcj.mums.ac.ir/article_2921.html

Ziaee, T., et al. 2014. The relationship between marital and sexual satisfaction among married women employees at Golestan University of Medical Sciences. Iran. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, 8(2), pp. 44-51. [PMID] [PMCID]

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.REC1397.027) and registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (Code: IRCT20180611040054N1). The study was conducted after obtaining approval from Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (Approval Number: 97/32620). An informed consent form was obtained from the study subjects after explaining to them the objectives of the study.

Funding

This study was part of the MSc thesis of Razia Hakimi in Midwifery performed in the International Campus of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS) and financially supported by the UNFPA and Italian Embassy.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in designing, running, and writing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Vice-Chancellors for International Affairs and Research and Technology of IUMS, Salsal Animation Center, all study subjects who participated in the study, UNFPA, Italian Embassy, and Kheir-ol-Bashar and Saheb-al-Zamanan charity centers in Mashhad.

References

Abedini, E., et al. 2016. A qualitative study on mothers’ experience from sex education to female adolescents underlining culture factors. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health, 18(4), pp. 202-11. http://eprints.mums.ac.ir/1925/

Central Statistics Organization., 2018. Afghanistan living conditions survey 2016-17 [Internet]. Cited 6 June 2020, https://www.ilo.org/surveyLib/index.php/catalog/2114/download/17907

Alimohammadi, L., et al. 2018. The effectiveness of group counseling based on bandura’s self-efficacy theory on sexual function and sexual satisfaction in Iranian newlywed women: a randomized controlled trial. Applied Nursing Research, 42, pp. 62-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.apnr.2018.06.011] [PMID]

Baradaran-Akbarzadeh, N., et al. 2018. The effect of educational package on sexual function in cold temperament women of reproductive age. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 7, p. 65. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_7_18] [PMID] [PMCID]

Behboodi Moghadam, Z., et al. 2015. The effect of sexual health education program on women sexual function in Iran. Journal of Research in Health Sciences, 15(2), pp. 124-8. [PMID]

Brotto, L. A. & Basson, R., 2014. Group mindfulness-based therapy significantly improves sexual desire in women. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, pp. 43-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.001] [PMID]

Fakhri, A., et al 2011. Psychometric properties of iranian version of female sexual function index. Jundishapur Scientific Medical Journal 10(4), pp. 345-54. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=208887

Hadi, M. 2016. An analysis of policy and social factors impacting the uptake of sexual and reproductive health services in Kabul, Afghanistan [PhD. thesis]. Durham: University of Durham. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11862/

Hindin, M. J. & Fatusi, A. O., 2009. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing countries: An overview of trends and interventions. International perspectives on sexual and reproductive health, 35(2), pp. 58-62. [DOI:10.1363/3505809] [PMID]

Hosain, G. M., et al. 2013. Racial differences in sexual dysfunction among postdeployed Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. American Journal of Men’s Health, 7(5), pp. 374-81. [DOI:10.1177/1557988312471842] [PMID] [PMCID]

Jahanfar, S. & Molaie Nejad, M., 2013. Sexual dysfunction syllabus. Tehran: Jame-e-Negar Publishing House. http://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/bibliographic/3397039

Karimi MoonaghI, H., et al. 2012. A comparison of face-to-face and video-based education on attitude related to diet and fluids: Adherence in hemodialysis patients. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 17(5), pp. 360-4. [PMID] [PMCID]

Kaviani, M., et al. 2014. The effect of education on sexual health of women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Community based Nursing and Midwifery, 2(2), pp. 94-102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4201195/

Khaki Rostami, Z., et al. 2015. Sexual dysfunction and help seeking behaviors in newly married women in Sari, Iran: A cross-sectional study. Payesh, 14(6), pp. 677-86. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=465777

Kheyrkhah, M., Vahedi, M. & Jenani, P., 2014. The effect of group counselling on infrtility adjustment of infertile women in Tabriz Al-Zahra clinic. Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility, 17(113), pp. 7-14. http://eprints.mums.ac.ir/4230/

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., Akhalaghi-Yazdi, R. & Hojati Sayah, M. Investigating gestalt-based play therapy on anxietyand loneliness in female children labour with sexual abuse: A Single Case Research Design (SCRD), 2019. Journal of Client-Centered Nursing Care, 5(3), pp. 147-56. [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.5.3.147]

Mahmoudi, G., Hasanzadeh, R. & Niazi Azar, K., 2007. [The effect of sex education on family health on Mazandaran medical university students (Persian)]. The Horizon of Medeical Science, 13(2), pp. 64-70. http://hms.gmu.ac.ir/article-1-168-en.html

Mazinani, R., et al. 2013. [Evaluation of prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and its related factors in women (Persian)]. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences, 19(105), pp. 59-66. http://rjms.iums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=2402&sid=1&slc_lang=en

Mohammadsadeg, A., Kalantar-Kosheh, S. M. & Naeimi, E., 2018. [The Experience of sexual problems in women seeking divorce and women satisfied with their marriage: A qualitative study(Persian)]. Journal of Qualtative Research in Health Sciences, 7(1), pp. 35-47. http://jqr.kmu.ac.ir/article-1-634-en.html

Mohammadshahi, M., et al. 2014. Comparing two different teaching methods: Traditional and teblog-based teaching (wbt) by group discussion. Educational Development of Jundishapur, 5(2), pp. 157-64. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=428708

Ortega-Maldonado, A., et al. 2017. Face-to-Face vs On-line: An analysis of profile, learning, performance and satisfaction among post graduate students. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 5(10), pp. 1701-6. [DOI:10.13189/ujer.2017.051005]

Refaie Shirpak, K., et al. 2007. Developing and testing a sex education program for the female clients of health centers in Iran. Sex Education, 7(4), pp. 333-49. [DOI:10.1080/14681810701636044]

Rosen, R., et al. 2000. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26(2), pp. 191-208. [DOI:10.1080/009262300278597] [PMID]

Sadri Damirchi, E., Poorzor, P. & Esmaili Ghazivaloii, F., 2016. [Effectiveness of sexual skills education on sexual attitude and knowledge in married women (Persian)]. Journal of Family Counseling & Psychotherapy, 6(1), pp. 1-15. http://fcp.uok.ac.ir/article_42720_en.html

Sargazi, M., et al. 2014. Effect of an Educational Intervention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior on behaviors leading to early diagnosis of Breast Cancer among women referred to health care centers in Zahedan in 2013. Iranian Quarterly Journal of Breast Diseases, 7(2), pp. 45-55. http://ijbd.ir/article-1-342-en.html

Shakerian, A., et al. 2014. Inspecting the relationship between sexual satisfaction and marital problems of divorce-asking women in sanandaj city family courts. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, pp. 327-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.706]

Sharifi, F., Feyzi, A. & Arteshehdar, E., 2013. [Knowledge and satisfaction of medical students with two methods of education for endocrine pathophysiology course: E-learning and lecture in classroom (Persian)]. Journal of Medical Education Development, 6(11), pp. 30-40. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=408326

Talaizadeh, F. & Bakhtiyarpour, S., 2016. [The relationship between marital satisfaction and sexual satisfaction with couple mental health (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology Andisheh va Raftar, 11(40), pp. 37-46. https://jtbcp.riau.ac.ir/article_939_en.html

Tavakol, Z., et al. 2012. [The relationship between sexual function and sexual satisfaction in women referring to centers sanitary health south of Tehran (Persian)]. Avicenna Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Care (Scientific Journal of Hamadan Nursing & Midwifery Faculty), 19(2), pp. 50-4. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=264138

Tulloch, T. & Kaufman, M., 2013. Adolescent sexuality. Pediatrics in Review, 34(1), pp. 29-38. [DOI:10.1542/pir.34-1-29] [PMID]

UNFPA., 2012. Marrying too young: End child marriage [Internet]. Cited 6 June 2020, https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/MarryingTooYoung.pdf [Accessed 5 March 2019].

UNICEF., 2014. Ending child marriage progress and prospects [Internet]. Cited 6 June 2020, https://www.unicef.org/media/files/Child_Marriage_Report_7_17_LR..pdf

UNICEF., 2018. Child marriage latest trends and future prospects [Internet]. Cited 6 June 2020, https://data.unicef.org/resources/child-marriage-latest-trends-and-future-prospects/

WHO., 2014. Health for the World’s Adolescents [Internet]. Cited 6 June 2020, http://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/files/1612_MNCAH_HWA_Executive_Summary.pdf [Accessed 4 March 2019].

XU, J. H., 2016. Toolbox of teaching strategies in nurse education. Chinese Nursing Research, 3(2), pp. 54-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.cnre.2016.06.002]

Yousefzadeh, S., Golmakani, N. & Nameni, F., 2017. The comparison of sex education with and without religious thoughts in sexual function of married women. Journal of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, 5(2), pp. 904-10. http://jmrh.mums.ac.ir/article_8384.html

Ziaee, P., Sepehri Shamlou, Z. & Mashhadi, A., 2014. The effectiveness of sexual education focused on cognitive schemas, on the improvement of sexual functioning among female married students. Evidence Based Care Journal, 4(2), pp. 73-82. http://ebcj.mums.ac.ir/article_2921.html

Ziaee, T., et al. 2014. The relationship between marital and sexual satisfaction among married women employees at Golestan University of Medical Sciences. Iran. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, 8(2), pp. 44-51. [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2020/03/3 | Accepted: 2020/04/25 | Published: 2020/06/1

Received: 2020/03/3 | Accepted: 2020/04/25 | Published: 2020/06/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |