Fri, Jul 18, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 7, Issue 2 (Spring 2021)

JCCNC 2021, 7(2): 97-108 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Aghaei-Malekabadi M, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee A, Afkari F. Effects of CALM and SPACE Parent Training Programs on Rumination and Anxiety in Mothers With Bully Sons. JCCNC 2021; 7 (2) :97-108

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-282-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-282-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tehran North Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology & Educational Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Khatam University, Tehran, Iran. ,a.khodabakhshid@khatam.ac.ir

3- Department of Educational Science, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tehran North Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology & Educational Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Khatam University, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Educational Science, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tehran North Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 796 kb]

(1192 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4205 Views)

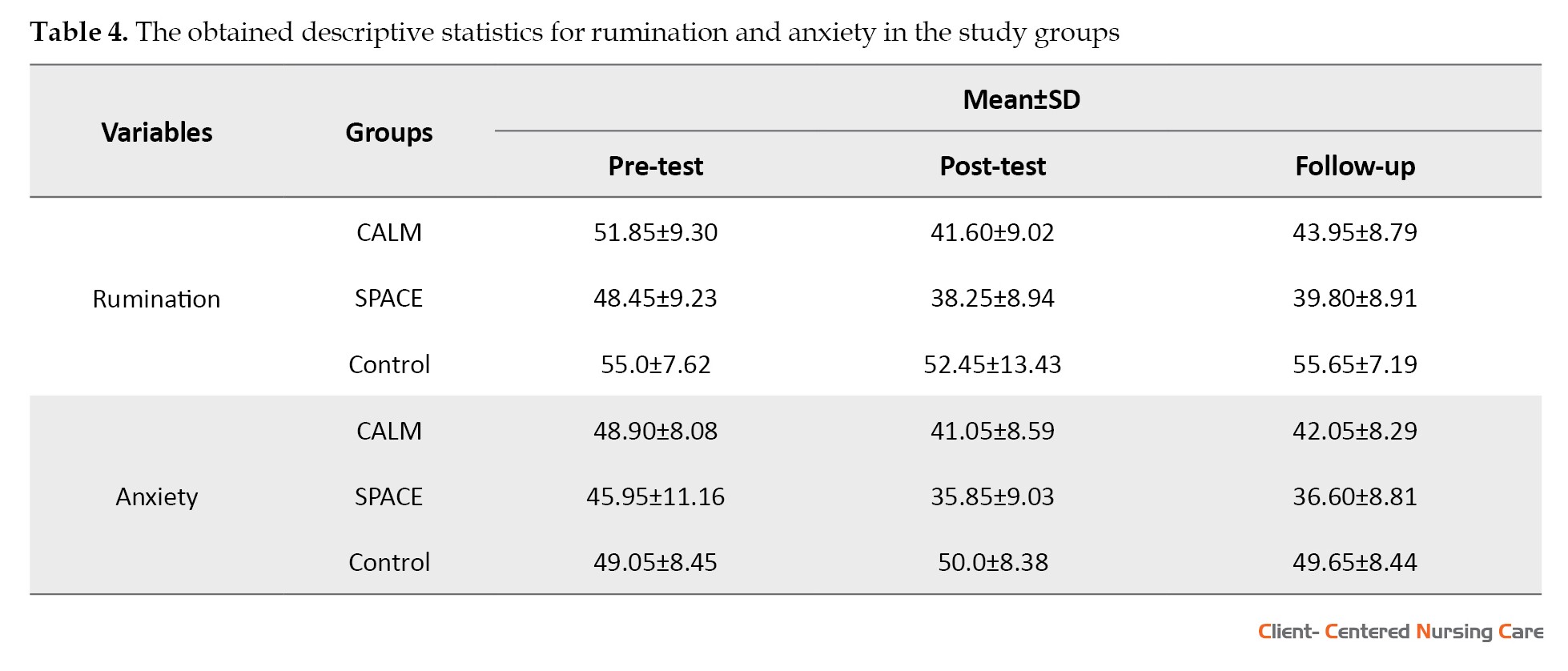

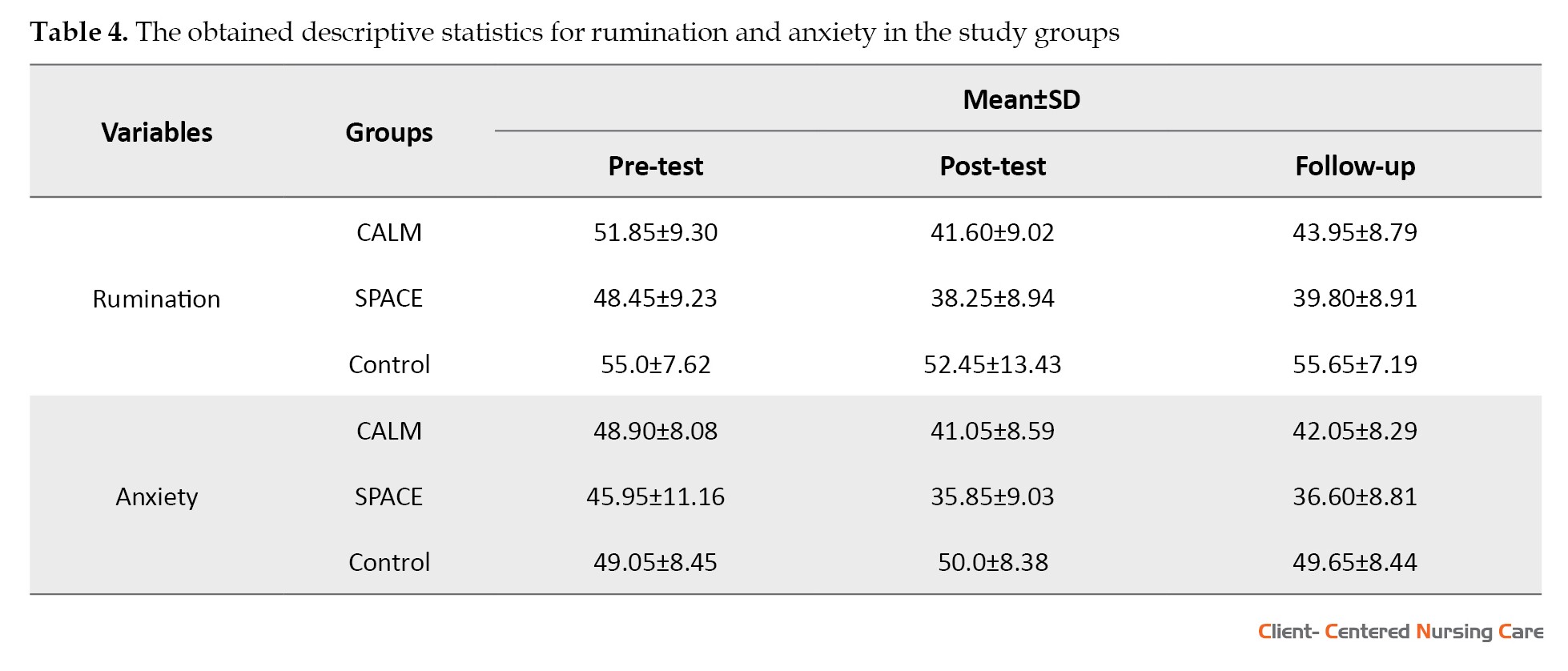

Table 4 displays the Mean±SD scores of the dependent variables in pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages in all study groups. The Independent Samples t-test data indicated no significant differences in the pre-test scores of the intervention groups and the controls concerning the dependent variables (P>0.05).

As per Table 4, SPACE and CALM programs could reduce the mean scores of rumination and anxiety reported by the mothers in the post-test and follow-up stages. However, inferential statistics were used to examine if differences were significant. It was revealed that both study programs were effective in reducing maternal rumination and anxiety in the post-test and follow-up stages. Before running the repeated-measures ANOVA, the assumptions of parametric tests were checked. Accordingly, the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test suggested that the assumption of the normal distribution of the data for rumination and anxiety in the intervention and control groups was established in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages (P<0.05). Besides, the assumption of homogeneity of variances was measured by Levene’s test. The relevant results were not significant, indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variances was established (P>0.05). Furthermore, the Box’s M test data revealed that the equality of multiple variance-covariance matrices was established; thus, the F-test could be implemented. The results of Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated that the data sphericity assumption was not observed for rumination and anxiety. Accordingly, the assumption of sphericity was not established, indicating the relationships between the variables were subject to change the values of the dependent variable; thus, enhancing the odds of type I error rates. Accordingly, the alternative analysis (Greenhouse–Geisser correction) was used to reduce the odds of type I error by reducing the degree of freedom.

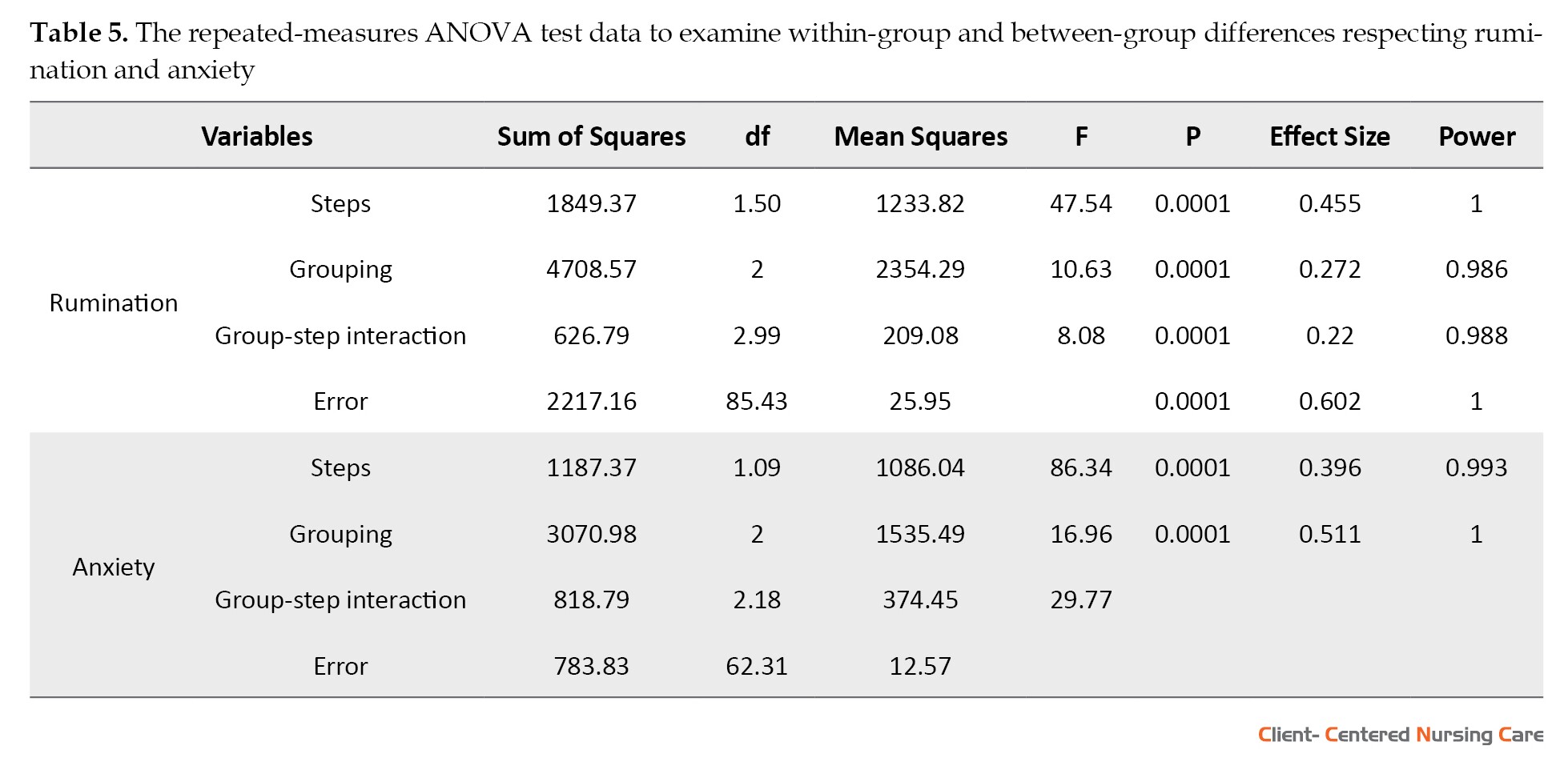

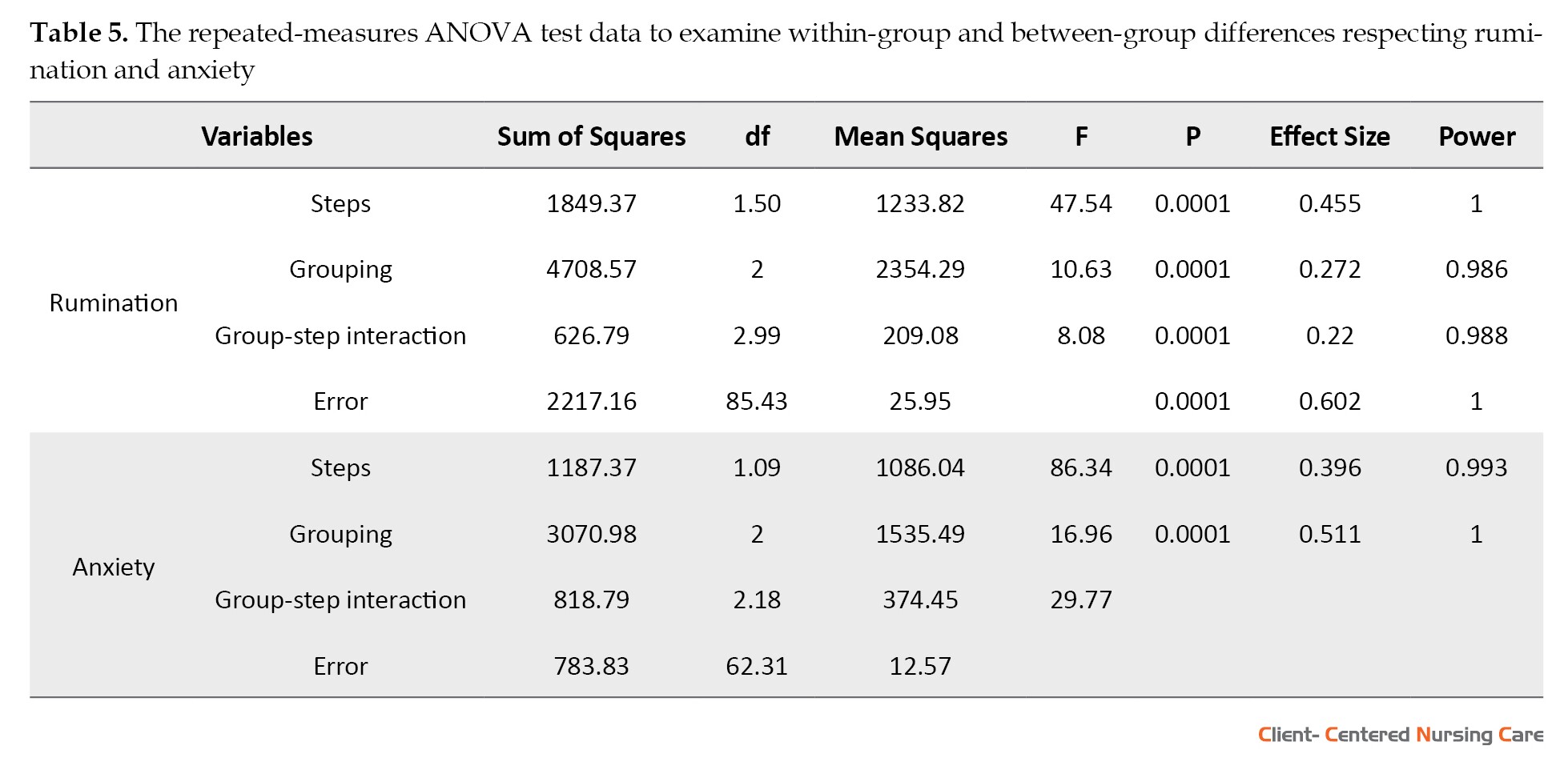

The results of Greenhouse–Geisser correction test identified that the time or step of assessment significantly affected maternal rumination and anxiety; this finding explained 45% and 60% of the differences in the variances of these variables, respectively. Besides, the effect of group membership (SPACE & CALM programs) was significant on maternal rumination and anxiety scores; accordingly, this statistic explained 27% and 39% of the difference in the scores of these variables, respectively. These findings suggested that the effect of the type of treatment and time factor interaction on rumination and maternal anxiety scores was significant and explained 22% and 51% of the difference in maternal rumination and anxiety scores, respectively. The statistical power indicates high statistical accuracy and adequate sample size. Overall, SPACE and CALM programs affected maternal rumination and anxiety in different steps. Table 5 demonstrated the pairwise comparisons of the mean scores of rumination and anxiety in the study participants according to the evaluation step.

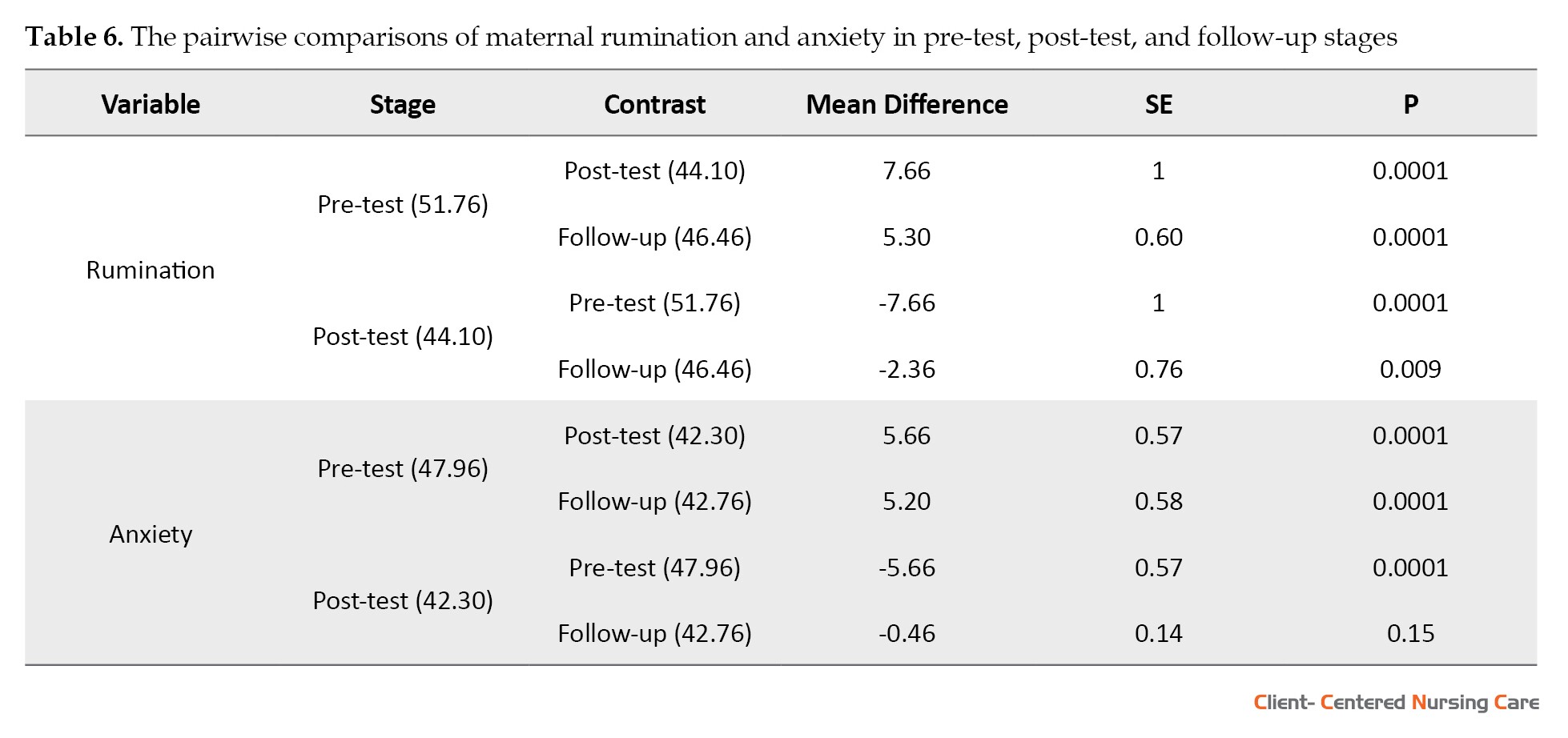

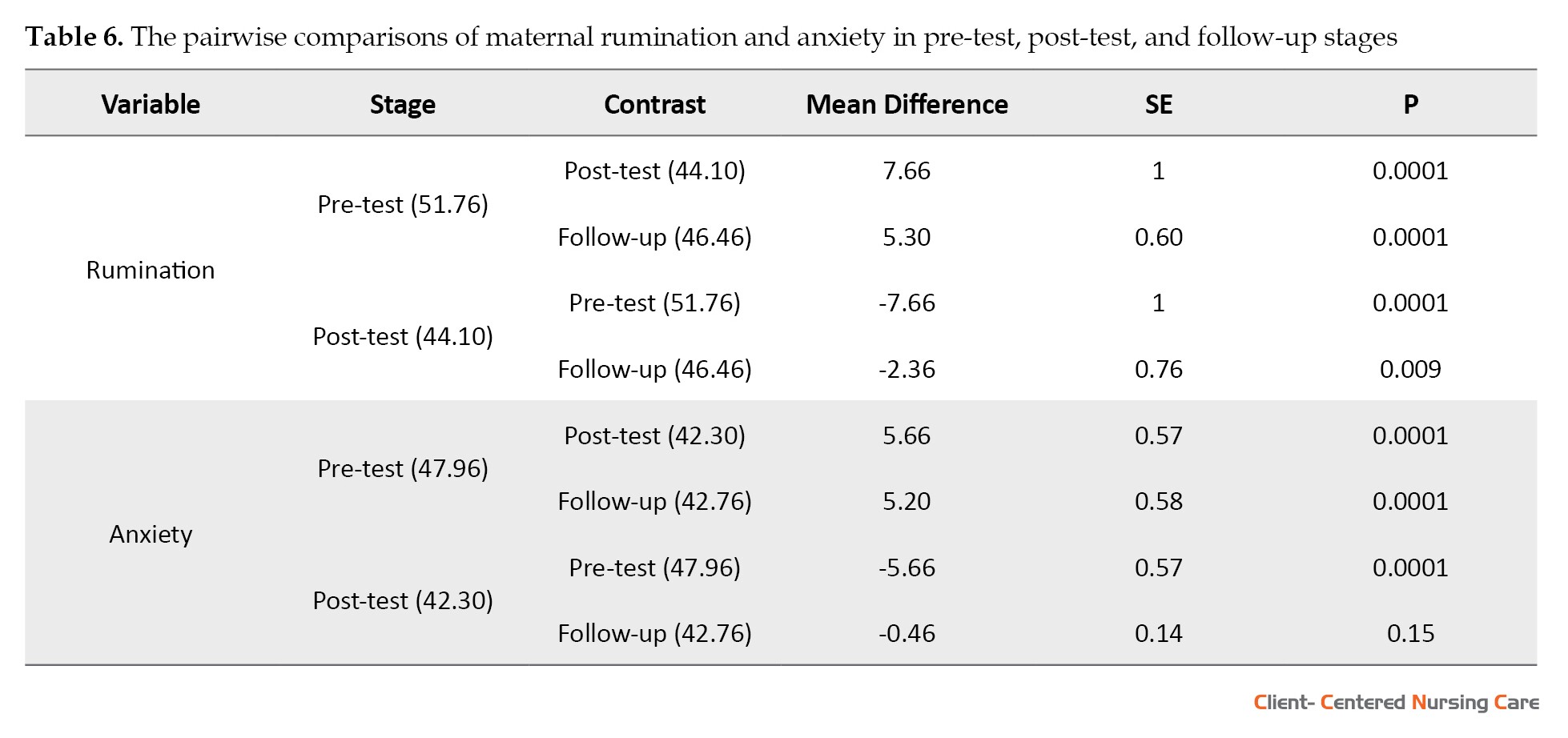

As per Table 5, there was a significant difference between the mean scores of rumination and anxiety in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages. This finding suggests that SPACE and CALM programs significantly reduced rumination and anxiety in the post-test and follow-up steps, compared to the pre-test stage. The results of descriptive statistics signified a decrease in the mean scores of maternal rumination and anxiety after the intervention. There was no significant difference in the mean scores of maternal rumination and anxiety between the post-test stage and follow-up stages. Accordingly, the mean scores of maternal rumination and anxiety significantly reduced in the post-test; the observed changes in these variables were also retained in the follow-up stage. Overall, the CALM and SPACE programs significantly reduced the mean scores of maternal rumination and anxiety in the post-test and also follow-up stages. Table 6 lists the pairwise comparisons of the mean scores of rumination and anxiety in the study participants by group.

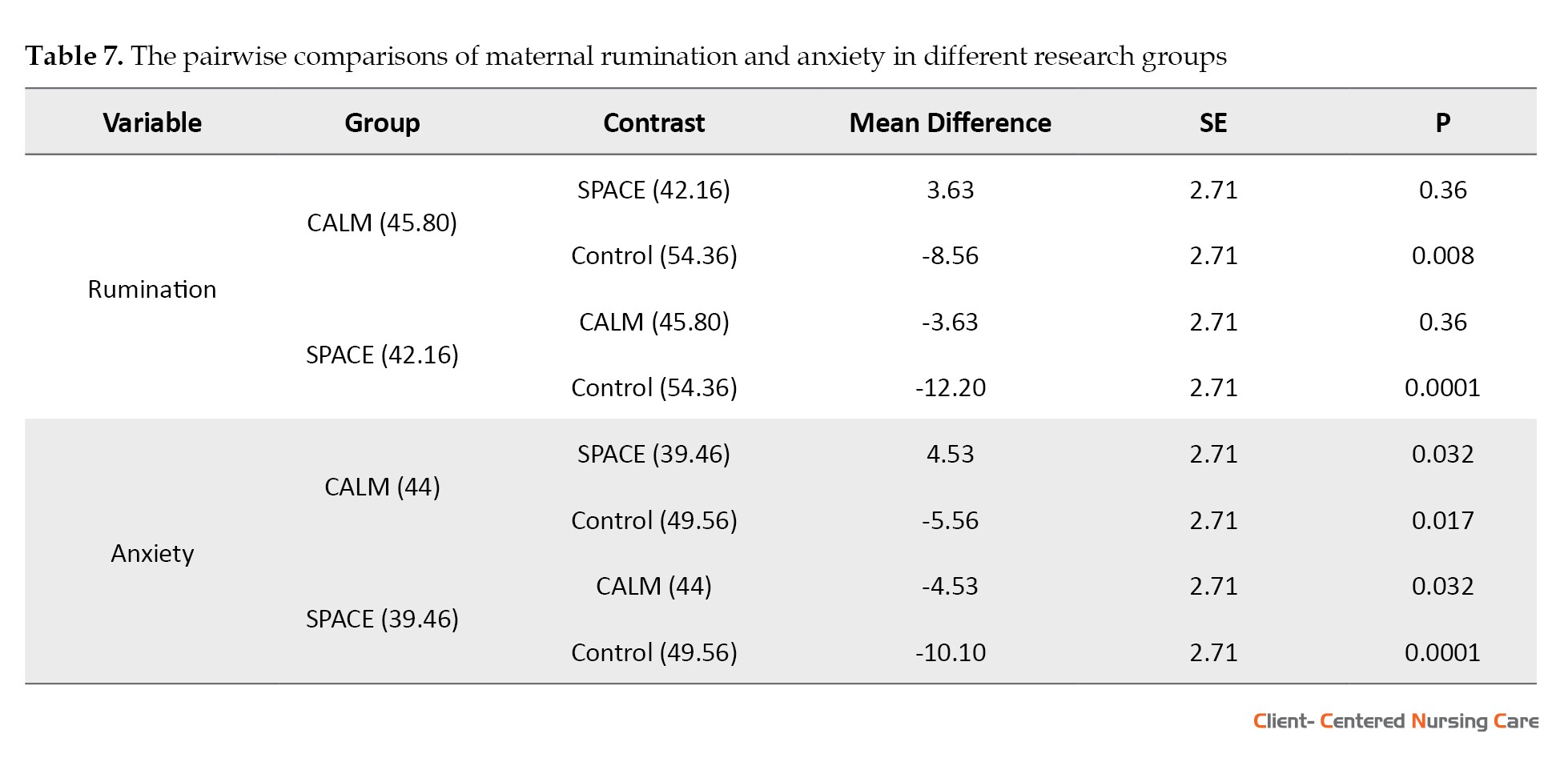

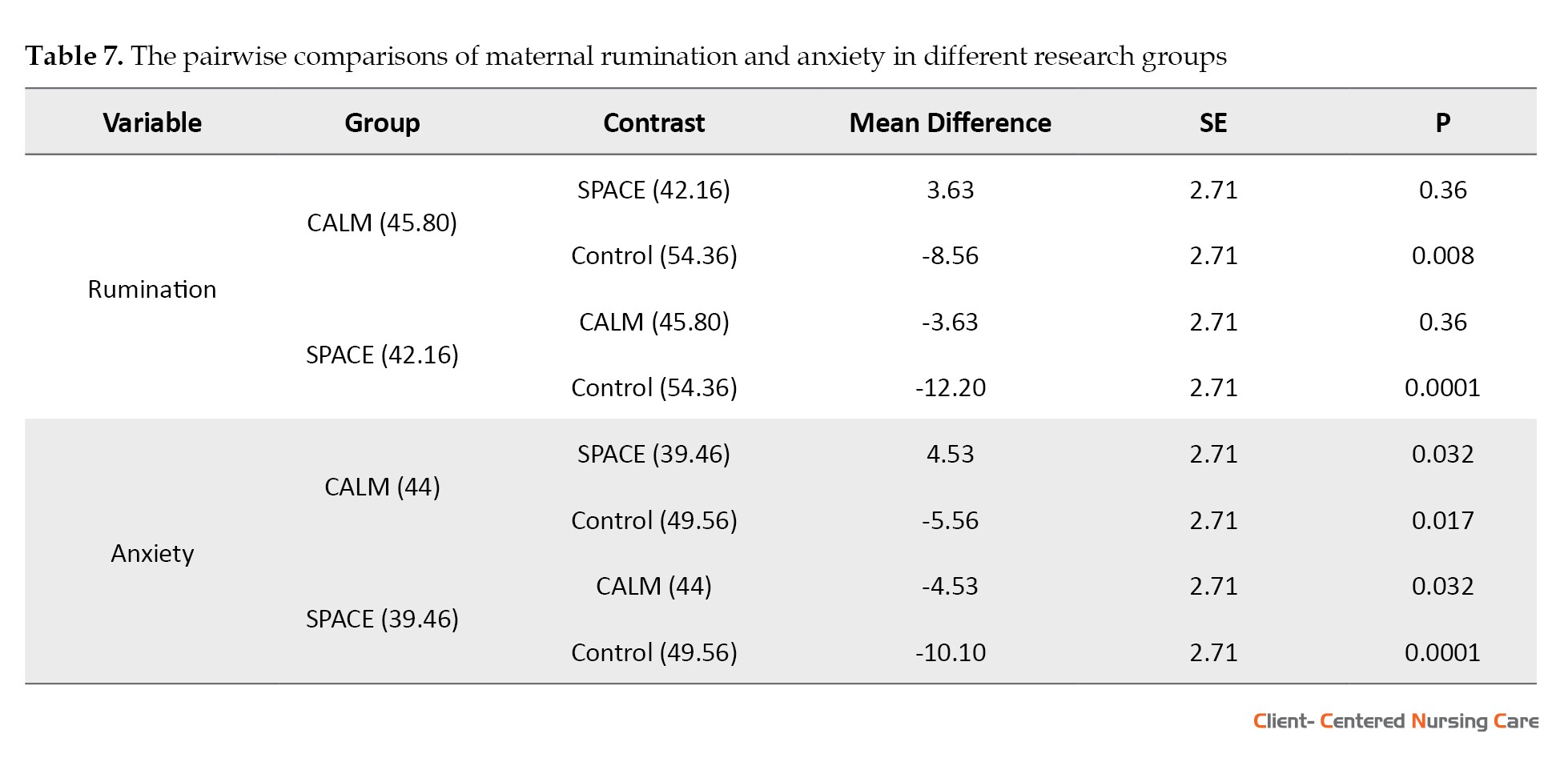

Moreover, significant differences existed between the CALM (45.80), SPACE (42.16), and control (54.36) groups in terms of rumination (P<0.05) (Table 7). Therefore, the CALM and SPACE programs reduced the examined mothers’ rumination. However, there was no significant difference in the mean scores of ruminations between the CALM (45.80) and SPACE (42.16) groups (P≥0.05); accordingly, the CALM and SPACE programs were not different respecting effectiveness in reducing the explored mothers’ rumination. Moreover, there was a significant difference in the mean scores of anxiety group the CALM (44) and SPACE (39.46) groups (P<0.05); thus, both provided programs effectively reduced the examined mothers’ anxiety (P<0.05). Furthermore, the SPACE program was more effective than the CALM program in reducing the study participants’ anxiety.

• Parenting training programs help parents gain an understanding of their children’s psychological, emotional, and behavioral problems.

• Bullying behavior is an intentional and repeated physical, verbal, or psychological pressure on weaker subjects by a stronger individual. Bullying individuals have educational, interpersonal, and psychological problems.

• The explored mothers with bullying sons have reported mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety. Moreover, they are always blamed by the school and other parents, because of their son’s behaviors.

• The CALM and SPACE programs were effective in reducing maternal rumination and anxiety. However, CALM was more effective than SPACE in reducing maternal anxiety.

Plain Language Summary

Parent training programs help parents to learn the best ways to correct their children’s behaviors and have a better relationship with the child. The CALM and SPACE programs could help mothers improve their parent-child relationship; this is achieved by recognizing their children’s psychological and behavioral problems and reduce their problems and worries of themselves, such as anxiety and rumination. This research revealed that the mentioned programs helped the mothers of bullying sons to reduce their anxiety and rumination.

• Bullying behavior is an intentional and repeated physical, verbal, or psychological pressure on weaker subjects by a stronger individual. Bullying individuals have educational, interpersonal, and psychological problems.

• The explored mothers with bullying sons have reported mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety. Moreover, they are always blamed by the school and other parents, because of their son’s behaviors.

• The CALM and SPACE programs were effective in reducing maternal rumination and anxiety. However, CALM was more effective than SPACE in reducing maternal anxiety.

Plain Language Summary

Parent training programs help parents to learn the best ways to correct their children’s behaviors and have a better relationship with the child. The CALM and SPACE programs could help mothers improve their parent-child relationship; this is achieved by recognizing their children’s psychological and behavioral problems and reduce their problems and worries of themselves, such as anxiety and rumination. This research revealed that the mentioned programs helped the mothers of bullying sons to reduce their anxiety and rumination.

Full-Text: (1152 Views)

1. Introduction

Before the 1990s, bullying was considered a subset of aggressive behavior in children and adolescents. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention studied bullying in particular to prevent violence in 2019 and considered it a type of violence threatening individuals’ health (Dawoud 2020). Peter-Paul Heinemann, a Swedish physician, first coined the term mobbing in 1969. Based on his observations, he proposed a hypothesis for understanding human destructive behavior. Another Swedish psychologist, Dan Olweus, later presented a different definition of a bully and a victim child. He considered a bully as an aggressive and impulsive individual who requires domination (Thomas Cook 2020). About one-third of children in primary school are involved in bullying (De Vries et al. 2017). Currently, 15%-30% of students are affected by bullying and its consequences (Hosseini & Rhmadrash 2020). The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) data suggest that 246 million children and adolescents experience school violence, annually. In 2019, 32% of students in the world were bullied (Muhopliah, Tentama & Yuzarion 2020). According to studies conducted in Iran, about 80% of students believe in the presence of bullying. Another study reported a prevalence of bullying to be 38.4% among students aged 10 to 14 years (Hosseini & Rhmadrash 2020; Khodabakhshi-koolaee & Darestani-Farahani 2020). Olweus defines bullying as a negative, repetitive activity characterized by a power imbalance between the bully and the victim. It can be considered an intentional and repeated physical, verbal, or psychological pressure on a weaker subject by an individual or a group of stronger individuals, i.e., usually associated with an unequal power between the involved parties. Bullying includes 4 main components, as follows: voluntariness and intentionality; persistence; power imbalance between the parties to the conflict, and occurrence in familiar social groups. Bullying is demonstrated either physically, directly or indirectly, and emotionally (Hosseini & Rhmadrash 2020). It is considered a multifactorial phenomenon, i.e., affected by the accumulation of individual, family, school, and social factors (Valle & Williams 2020).

Maternal mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety increase the risk of behavioral problems in children (Garcia & O' Neil 2020). Parents’ mental health, their interaction with the child, and other life events, i.e., interpreted by the child significantly impact the assessment of children’s behavioral problems. The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in females is approximately 40%; twice as high as in males (Gregory et al. 2020). High levels of parental anxiety lead to inadequate formation of Emotion Regulation (ER) skills. Anxiety in mother-child relationships, in turn, affects the social learning processes; thus, such conditions lead to unsuitable parent-child role modeling and the child learns inefficient ER strategies (Jamali & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee 2019).

Anxiety is a response to real or potential threats and can jeopardize an individual’s state of balance and homeostasis (Garcia & O' Neil, 2020). It is a common type of emotional disorder that disrupts a subject’s psychological functioning (Pang, Tu & Cai 2019). Research on rumination dates back to studies by scholars, like Aron Temkin Beck followed by Nolen-Hoeksema’s research that highlighted a strong relationship between rumination thoughts and emotional disorders. Rumination predicts the onset of anxiety and triggers psychological stimulation and a negative emotional state (Feldhaus et al., 2020). It is a subject’s mood in response to anxiety and involves an extensive passive focus on disturbing symptoms and their causes. Individuals often tend to reflect on the causes and negative consequences of events and overlook solutions (Chen et al. 2017). Over the past 3 decades, numerous interventions and programs were developed and implemented in different parts of the world, especially in Europe and North America, to combat bullying; these programs were often school-based (Olweus, Solberg & Breivik 2020). Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP) is the most widely used anti-bullying program in schools. Most of these programs are student-centered (Olweus, Solberg & Breivik 2020; Karats & Ozturk 2020; Bandi 2019).

Coaching Approach Behavior and Leading by Modeling (CALM) program is an adaptation of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT). Polyafico et al. modified the treatment techniques based on parent-child interactions to target separation anxiety disorders as well as other anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, and specific phobias. The first stage involves Child-Directed Interactions (CDI). The second step addresses the special and unique aspect of the program. At this stage, special skills are taught to the parents, known as the DADDS (D: Escribe feared situation; A: Pproach feared situation (modeling); D: Irect command for child to approach; S: Tate intent to remain in situation and provide selective attention) steps, and determined based on positive attention to model brave behaviors and ignore anxiety-related symptoms (Bandi 2019; Puliafico, Comer & Albano 2013). It is a direct and short-term treatment that uses an innovative method with live guidance and indirect training through the bug in the ear to treat various anxiety problems in children. It requires skills training for parents to effectively manage their child’s problematic behaviors (Puliafico, Comer & Albano 2013).

The Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions (SPACE) program was developed by Lebowitz. It is a suitable treatment for children aged 2-8 years and relies on parental education (Lebowitz 2013). It consists of 8 treatment parts and 5 modules at the discretion of the therapist, which allows treatment specifically with parents without the participation of their children (Lebowitz et al. 2014).

The SPACE program is an intervention for parental adaptive behaviors and concerns the child’s anxiety. It does not teach specific skills to parents; however, SPACE focuses on how parents interact with the child and the characteristics of their relationship (Bui, Charney & Baker, 2020). There exists a gap in the literature despite the key role played by parents in increasing their child’s ability to adapt to bullying. Accordingly, relatively few studies have focused on mental health and increasing parental adjustment (Benatov 2019). The analysis of anti-bullying programs indicates that an essential element of successful programs is to involve parents in parenting education sessions (Van Niejenhuis, Huitsing, & Veenstra 2020). Previous research identified the positive impact of anti-bullying programs. However, programs that cover broader areas, like parent-teacher involvement are more effective (Khodabakhshi Koolaee et al. 2015; Grief Green et al. 2020). Although the role of parenting is a widely researched area, variables, such as rumination and maternal anxiety in how to manage a bully child remain unaddressed. Research on the SPACE program has focused on anxiety disorders (Lebowitz, 2013) and obsessive-compulsive disorders (Lebowitz et al. 2014). Furthermore, studies on the CALM program have mainly focused on anxiety (Puliafico, Comer & Albano 2013). These programs were translated into Persian for the first time and implemented among the Iranian population. These programs were developed to help mothers solve their children’s behavioral problems. Besides, child bullying, as one of the most important issues in schools and families, has been addressed with a focus on educating mothers. The present study aimed to determine the effects of the CALM and the SPACE programs on rumination and anxiety in mothers with bully sons.

Maternal mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety increase the risk of behavioral problems in children (Garcia & O' Neil 2020). Parents’ mental health, their interaction with the child, and other life events, i.e., interpreted by the child significantly impact the assessment of children’s behavioral problems. The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in females is approximately 40%; twice as high as in males (Gregory et al. 2020). High levels of parental anxiety lead to inadequate formation of Emotion Regulation (ER) skills. Anxiety in mother-child relationships, in turn, affects the social learning processes; thus, such conditions lead to unsuitable parent-child role modeling and the child learns inefficient ER strategies (Jamali & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee 2019).

Anxiety is a response to real or potential threats and can jeopardize an individual’s state of balance and homeostasis (Garcia & O' Neil, 2020). It is a common type of emotional disorder that disrupts a subject’s psychological functioning (Pang, Tu & Cai 2019). Research on rumination dates back to studies by scholars, like Aron Temkin Beck followed by Nolen-Hoeksema’s research that highlighted a strong relationship between rumination thoughts and emotional disorders. Rumination predicts the onset of anxiety and triggers psychological stimulation and a negative emotional state (Feldhaus et al., 2020). It is a subject’s mood in response to anxiety and involves an extensive passive focus on disturbing symptoms and their causes. Individuals often tend to reflect on the causes and negative consequences of events and overlook solutions (Chen et al. 2017). Over the past 3 decades, numerous interventions and programs were developed and implemented in different parts of the world, especially in Europe and North America, to combat bullying; these programs were often school-based (Olweus, Solberg & Breivik 2020). Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP) is the most widely used anti-bullying program in schools. Most of these programs are student-centered (Olweus, Solberg & Breivik 2020; Karats & Ozturk 2020; Bandi 2019).

Coaching Approach Behavior and Leading by Modeling (CALM) program is an adaptation of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT). Polyafico et al. modified the treatment techniques based on parent-child interactions to target separation anxiety disorders as well as other anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, and specific phobias. The first stage involves Child-Directed Interactions (CDI). The second step addresses the special and unique aspect of the program. At this stage, special skills are taught to the parents, known as the DADDS (D: Escribe feared situation; A: Pproach feared situation (modeling); D: Irect command for child to approach; S: Tate intent to remain in situation and provide selective attention) steps, and determined based on positive attention to model brave behaviors and ignore anxiety-related symptoms (Bandi 2019; Puliafico, Comer & Albano 2013). It is a direct and short-term treatment that uses an innovative method with live guidance and indirect training through the bug in the ear to treat various anxiety problems in children. It requires skills training for parents to effectively manage their child’s problematic behaviors (Puliafico, Comer & Albano 2013).

The Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions (SPACE) program was developed by Lebowitz. It is a suitable treatment for children aged 2-8 years and relies on parental education (Lebowitz 2013). It consists of 8 treatment parts and 5 modules at the discretion of the therapist, which allows treatment specifically with parents without the participation of their children (Lebowitz et al. 2014).

The SPACE program is an intervention for parental adaptive behaviors and concerns the child’s anxiety. It does not teach specific skills to parents; however, SPACE focuses on how parents interact with the child and the characteristics of their relationship (Bui, Charney & Baker, 2020). There exists a gap in the literature despite the key role played by parents in increasing their child’s ability to adapt to bullying. Accordingly, relatively few studies have focused on mental health and increasing parental adjustment (Benatov 2019). The analysis of anti-bullying programs indicates that an essential element of successful programs is to involve parents in parenting education sessions (Van Niejenhuis, Huitsing, & Veenstra 2020). Previous research identified the positive impact of anti-bullying programs. However, programs that cover broader areas, like parent-teacher involvement are more effective (Khodabakhshi Koolaee et al. 2015; Grief Green et al. 2020). Although the role of parenting is a widely researched area, variables, such as rumination and maternal anxiety in how to manage a bully child remain unaddressed. Research on the SPACE program has focused on anxiety disorders (Lebowitz, 2013) and obsessive-compulsive disorders (Lebowitz et al. 2014). Furthermore, studies on the CALM program have mainly focused on anxiety (Puliafico, Comer & Albano 2013). These programs were translated into Persian for the first time and implemented among the Iranian population. These programs were developed to help mothers solve their children’s behavioral problems. Besides, child bullying, as one of the most important issues in schools and families, has been addressed with a focus on educating mothers. The present study aimed to determine the effects of the CALM and the SPACE programs on rumination and anxiety in mothers with bully sons.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a quasi-experimental study with pre-test, post-test and a control group design. A three-month follow-up was also performed in this research. The setting was boys’ primary schools in district 4 of Tehran City, Iran, in 2020. The study population included the mothers of bullying sons who were recruited by voluntary convenience sampling method; accordingly, they were randomly assigned into 3 research groups. To this end, the researcher referred to one of the branches of the educational complex in Sepehr-e Marefat, in district 4 of Tehran. The bullying students were first identified with the help of the school principals and deputy principals as per the inclusion criteria. Next, the Illinois Bullying Scale (IBS) was administered to 70 bullying children. Eventually, 60 children who obtained the highest scores on the IBS were selected. The inclusion criteria were students generating disciplinary problems as per the school’s disciplinary records and engaging in bullying behaviors, as diagnosed by the IBS. The exclusion criteria were absence from >2 training sessions and the mother’s or child’s simultaneous participation in another psychological program. The sample size was calculated for each group to be 15 subjects based on the effect size of 0.25, alpha of 0.05, and test power of 0.80. The research subjects were assigned into two intervention groups and one control group by random blocking method (n=20/group) (the sample attrition rate equaled 15).

The following instruments were used to collect the necessary data in this research:

The Illinois Bullying Scale (IBS): The IBS was developed by Espelage and Holt (2001). It contains 18 items and 3 subscales, including bullying (9 items), victimization (4 items), and aggression (5 items) (Espelage & Holt 2001). Each item is scored on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from never (0) to ≥7 times (4). Each subscale is measured via a separate score. Subscale scores are computed by summing the respective items. Scores range from 0 to 74. A high score on each subscale indicates the respondent’s greater frequent engagement in the same behavior. The reliability index for the whole scale was estimated equal to 0.87 using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (Espelage & Holt 2001). In Iran, Balootbangan and Talepasand translated the questionnaire into Persian and reported the relevant Cronbach’s alpha coefficient as 0.87 for the total scale. The Content Validity Ratio (CVR) of the scale’s translated version was 0.72 and its Content Validity Index (CVI) was measured as 0.81 (Akbari Balootbangan & Talepasand, 2015). In this research, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total scale was equal to 0.75.

The Ruminative Response Scale (RRS): The RRS is a subscale of the Response Styles Questionnaire developed by Nolen Hoeksema and Morrow (1991). The scale contains 22 items, scored based on a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from never (1) to 4 (often), depending on the extent to which the respondent uses rumination as a response to boring moods. The total score is calculated as the sum of all individual items. The minimum and maximum obtainable scores are 22 and 88, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this scale ranges from 0.88 to 0.91 (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow 1991). Mansouri et al. (2012), in Iran, translated the scale into Persian and reported the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.90 for the total scale. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of its Persian version in this research was equal to 0.85.

Zung Self -rating Anxiety Scale (SAS): It was developed by Zung (1971). The SAS contains 20 items that measure anxiety levels. Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale. The total score ranges from 20 to 80. In total, 15 items measure emotional symptoms and 5 items assess physical symptoms. Items 5, 9, 13, and 19 are scored reversely. The reliability coefficient of this scale is 0.80, indicating its high reliability. The reliability of the scale was calculated as 0.87 using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in Iran. Besides, its face validity and content validity were also confirmed (Setyowati, Chung & Yusuf 2019). The reliability index of the scale was calculated as 0.77 by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in this study.

The researcher contacted the students’ mothers and provided the required explanations about the research project. Then, the RRS and SAS were completed by all participating mothers in the intervention and control groups. The research participants in each intervention group attended 13 training sessions.

The two programs were translated from English to Persian and divided into 45-minute sessions. The content of the SPACE program was extracted and translated into Persian by the researchers following a study by Lebowitz and associates (Lebowitz et al. 2014). This protocol was performed in thirteen 45-minute sessions. The CALM program was also translated and implemented in thirteen 45-minute sessions, following previous studies (Puliafico, Comer & Albano 2013; Cooper-Vince et al. 2016; Huang et al. 2019). The content of the training sessions is presented in Tables 1 and 2.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The sessions were conducted in groups by the researcher in the school hall of Sepehr-e Marefat Educational Complex, in district 4 of Tehran City, Iran. The mothers in both research groups attended the sessions two days a week (Sundays & Tuesdays) from 10 AM to 12 PM. All related guidelines, brochures, and pamphlets were prepared and distributed to the explored mothers. The researcher also provided her phone number to the mothers for further questions and guidance.

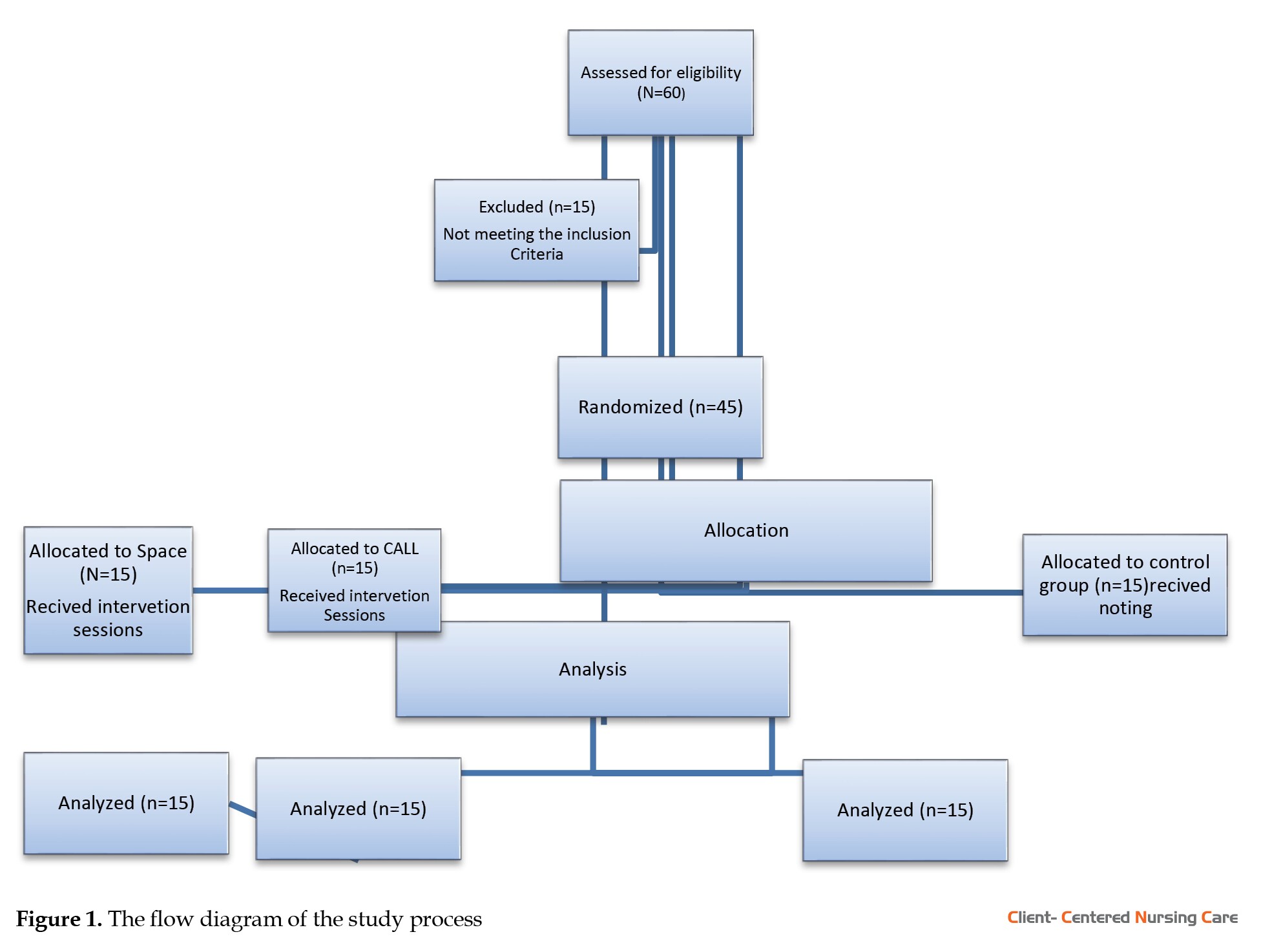

The questionnaires were re-administered to all study groups at the end of the intervention, also at the three-month follow-up phase to assess the retention effects of the provided programs. The chart of the study process is illustrated in Figure 1. Finally, after 3 months, the follow-up examination was administered to all research participants. The collected data were analyzed using repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) in SPSS v. 22.

The following instruments were used to collect the necessary data in this research:

The Illinois Bullying Scale (IBS): The IBS was developed by Espelage and Holt (2001). It contains 18 items and 3 subscales, including bullying (9 items), victimization (4 items), and aggression (5 items) (Espelage & Holt 2001). Each item is scored on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from never (0) to ≥7 times (4). Each subscale is measured via a separate score. Subscale scores are computed by summing the respective items. Scores range from 0 to 74. A high score on each subscale indicates the respondent’s greater frequent engagement in the same behavior. The reliability index for the whole scale was estimated equal to 0.87 using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (Espelage & Holt 2001). In Iran, Balootbangan and Talepasand translated the questionnaire into Persian and reported the relevant Cronbach’s alpha coefficient as 0.87 for the total scale. The Content Validity Ratio (CVR) of the scale’s translated version was 0.72 and its Content Validity Index (CVI) was measured as 0.81 (Akbari Balootbangan & Talepasand, 2015). In this research, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total scale was equal to 0.75.

The Ruminative Response Scale (RRS): The RRS is a subscale of the Response Styles Questionnaire developed by Nolen Hoeksema and Morrow (1991). The scale contains 22 items, scored based on a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from never (1) to 4 (often), depending on the extent to which the respondent uses rumination as a response to boring moods. The total score is calculated as the sum of all individual items. The minimum and maximum obtainable scores are 22 and 88, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this scale ranges from 0.88 to 0.91 (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow 1991). Mansouri et al. (2012), in Iran, translated the scale into Persian and reported the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.90 for the total scale. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of its Persian version in this research was equal to 0.85.

Zung Self -rating Anxiety Scale (SAS): It was developed by Zung (1971). The SAS contains 20 items that measure anxiety levels. Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale. The total score ranges from 20 to 80. In total, 15 items measure emotional symptoms and 5 items assess physical symptoms. Items 5, 9, 13, and 19 are scored reversely. The reliability coefficient of this scale is 0.80, indicating its high reliability. The reliability of the scale was calculated as 0.87 using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in Iran. Besides, its face validity and content validity were also confirmed (Setyowati, Chung & Yusuf 2019). The reliability index of the scale was calculated as 0.77 by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in this study.

The researcher contacted the students’ mothers and provided the required explanations about the research project. Then, the RRS and SAS were completed by all participating mothers in the intervention and control groups. The research participants in each intervention group attended 13 training sessions.

The two programs were translated from English to Persian and divided into 45-minute sessions. The content of the SPACE program was extracted and translated into Persian by the researchers following a study by Lebowitz and associates (Lebowitz et al. 2014). This protocol was performed in thirteen 45-minute sessions. The CALM program was also translated and implemented in thirteen 45-minute sessions, following previous studies (Puliafico, Comer & Albano 2013; Cooper-Vince et al. 2016; Huang et al. 2019). The content of the training sessions is presented in Tables 1 and 2.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The sessions were conducted in groups by the researcher in the school hall of Sepehr-e Marefat Educational Complex, in district 4 of Tehran City, Iran. The mothers in both research groups attended the sessions two days a week (Sundays & Tuesdays) from 10 AM to 12 PM. All related guidelines, brochures, and pamphlets were prepared and distributed to the explored mothers. The researcher also provided her phone number to the mothers for further questions and guidance.

The questionnaires were re-administered to all study groups at the end of the intervention, also at the three-month follow-up phase to assess the retention effects of the provided programs. The chart of the study process is illustrated in Figure 1. Finally, after 3 months, the follow-up examination was administered to all research participants. The collected data were analyzed using repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) in SPSS v. 22.

3. Results

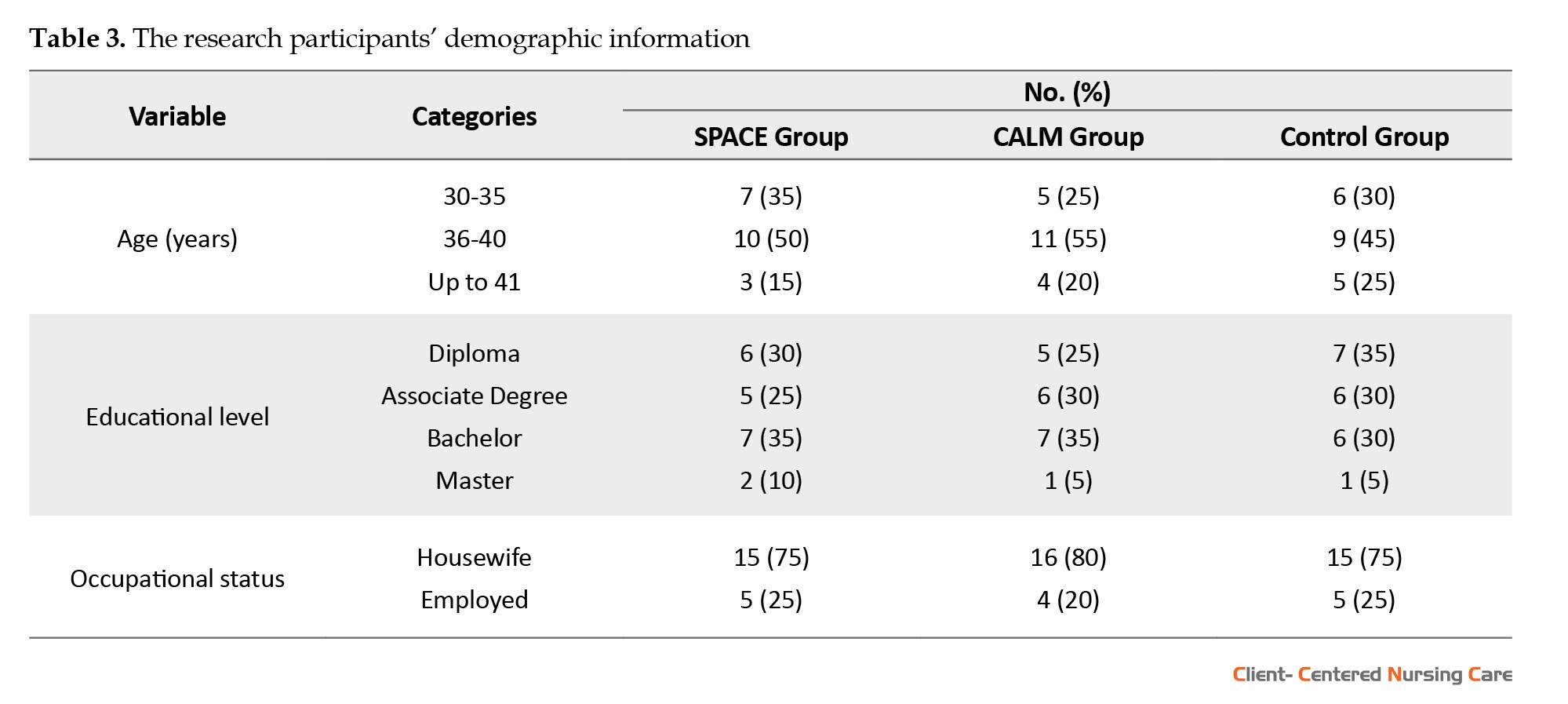

The study participants’ group-wise demographic data are presented in Table 3. There was no significant difference in age, educational level, and occupational status between the research subjects (P>0.05).

Table 4 displays the Mean±SD scores of the dependent variables in pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages in all study groups. The Independent Samples t-test data indicated no significant differences in the pre-test scores of the intervention groups and the controls concerning the dependent variables (P>0.05).

As per Table 4, SPACE and CALM programs could reduce the mean scores of rumination and anxiety reported by the mothers in the post-test and follow-up stages. However, inferential statistics were used to examine if differences were significant. It was revealed that both study programs were effective in reducing maternal rumination and anxiety in the post-test and follow-up stages. Before running the repeated-measures ANOVA, the assumptions of parametric tests were checked. Accordingly, the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test suggested that the assumption of the normal distribution of the data for rumination and anxiety in the intervention and control groups was established in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages (P<0.05). Besides, the assumption of homogeneity of variances was measured by Levene’s test. The relevant results were not significant, indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variances was established (P>0.05). Furthermore, the Box’s M test data revealed that the equality of multiple variance-covariance matrices was established; thus, the F-test could be implemented. The results of Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated that the data sphericity assumption was not observed for rumination and anxiety. Accordingly, the assumption of sphericity was not established, indicating the relationships between the variables were subject to change the values of the dependent variable; thus, enhancing the odds of type I error rates. Accordingly, the alternative analysis (Greenhouse–Geisser correction) was used to reduce the odds of type I error by reducing the degree of freedom.

The results of Greenhouse–Geisser correction test identified that the time or step of assessment significantly affected maternal rumination and anxiety; this finding explained 45% and 60% of the differences in the variances of these variables, respectively. Besides, the effect of group membership (SPACE & CALM programs) was significant on maternal rumination and anxiety scores; accordingly, this statistic explained 27% and 39% of the difference in the scores of these variables, respectively. These findings suggested that the effect of the type of treatment and time factor interaction on rumination and maternal anxiety scores was significant and explained 22% and 51% of the difference in maternal rumination and anxiety scores, respectively. The statistical power indicates high statistical accuracy and adequate sample size. Overall, SPACE and CALM programs affected maternal rumination and anxiety in different steps. Table 5 demonstrated the pairwise comparisons of the mean scores of rumination and anxiety in the study participants according to the evaluation step.

As per Table 5, there was a significant difference between the mean scores of rumination and anxiety in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages. This finding suggests that SPACE and CALM programs significantly reduced rumination and anxiety in the post-test and follow-up steps, compared to the pre-test stage. The results of descriptive statistics signified a decrease in the mean scores of maternal rumination and anxiety after the intervention. There was no significant difference in the mean scores of maternal rumination and anxiety between the post-test stage and follow-up stages. Accordingly, the mean scores of maternal rumination and anxiety significantly reduced in the post-test; the observed changes in these variables were also retained in the follow-up stage. Overall, the CALM and SPACE programs significantly reduced the mean scores of maternal rumination and anxiety in the post-test and also follow-up stages. Table 6 lists the pairwise comparisons of the mean scores of rumination and anxiety in the study participants by group.

Moreover, significant differences existed between the CALM (45.80), SPACE (42.16), and control (54.36) groups in terms of rumination (P<0.05) (Table 7). Therefore, the CALM and SPACE programs reduced the examined mothers’ rumination. However, there was no significant difference in the mean scores of ruminations between the CALM (45.80) and SPACE (42.16) groups (P≥0.05); accordingly, the CALM and SPACE programs were not different respecting effectiveness in reducing the explored mothers’ rumination. Moreover, there was a significant difference in the mean scores of anxiety group the CALM (44) and SPACE (39.46) groups (P<0.05); thus, both provided programs effectively reduced the examined mothers’ anxiety (P<0.05). Furthermore, the SPACE program was more effective than the CALM program in reducing the study participants’ anxiety.

4. Discussion

The present study compared the effects of the CALM and SPACE programs on rumination and anxiety in mothers with bully sons. The relevant results suggested that the SPACE program was more effective in reducing the examined mothers’ anxiety. The SPACE program is dynamic and adaptive. It simulates the treatment space with real-life conditions and problems; thus, it can generalize the findings to environments outside the research setting. Besides, the mother and child can simultaneously participate in the SPACE program; this is a crucial advantage of this program. The present study findings were in line with those of a study by Huang et al. (2019). They cited that school-based anti-bullying programs with a parent component are beneficial for controlling bullying children. Parents’ participants in school programs help the parent-child relationships (Huang et al. 2019).

Kaminetsky (2020) stated that that the CALM program increased mothers’ positive parenting skills, while their negative parenting skills decreased following treatment. This result highlights that the CALM program can be effective for reducing maternal and child anxiety.

The mother’s behavior can prepare the child to learn coping skills or be exposed to further problems (Brumariu & Kerns, 2015). Accordingly, Brumariu and Kerns (2015) found a relationship between the emotions of mothers and children and the onset of anxiety symptoms. The mothers of more anxious children provide less attention, love, and affection for their children and talk less to the child when something goes wrong. Additionally, more anxious mothers express less affection and love to their children; they are less likely to engage in conversations with the child when encountering a problem. Moreover, more anxious children are less likely to talk to others. Finally, they demonstrated that the type of behavior and emotions of anxious mothers present a reciprocal effect on their children’s anxiety. Furthermore, the CALM program familiars parents with the basic concepts of support and adjustment (Brumariu & Kerns, 2015). Lebowitz et al. (2020) argued that the SPACE program is highly appropriate for reducing anxiety in children. This program helps mothers and children by involving parents in the treatment process (Lebowitz et al., 2020). However, in another study, they identified no difference between the SPACE program and the cognitive-behavioral therapy, where both approaches were effective (Lebowitz et al., 2020). Furthermore, both programs were effective in reducing rumination in mothers. Ruminants focus on the content of thoughts and self-criticism. Self-Criticism and rumination are incompatible psychological processes that adversely affect parenting and increase parental stress (Lebowitz et al., 2020). Moreira and Canavarro (2018) studied the effects of rumination on parental stress and mindful parenting dimensions, including careful listening; compassion for the child; non-judgmental acceptance of parental performance; child’s emotional awareness, and ER in parents. The relevant results indicated that rumination was reversely associated with all aspects of mindful parenting dimensions and parental stress (Moreira & Canavarro, 2018). Generally, programs developed to inform and educate mothers can help reduce children’s behavioral problems. They are also effective in reducing parenting stress (Khodabakhshi Koolaee et al. 2015). Moreover, a short video tutorial for avoidant parents who had difficulty in effective communication with their child reduced their problematic communication and avoidance behaviors (Ewing et al., 2020). Jamali and Kolabakhshi-Koolaee concluded that the parenting behavior management training program reduces aggression and disobedience in boys (Jamali & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, 2019).

Overall, the CALM and SPACE programs were effective in reducing anxiety and rumination symptoms in the examined mothers. However, the CALM program was more effective in reducing anxiety symptoms than the SPACE program. The CALM program further emphasis on parent-child interactions (Harcourt, Jaseperse & Green 2014; Lebowitz & Shimshoni 2018). Besides, the CALM program provides the parent the power to coach and supervise during the session and enjoys a more suitable feedback system; therefore, it can help improve the parent-child relationship and parenting skills (Comer et al., 2012).

The research sample was limited to the mothers of male primary school students in Sepehr-e Marefat Educational Complex, district 4 of Tehran, i.e., a study limitation.

Kaminetsky (2020) stated that that the CALM program increased mothers’ positive parenting skills, while their negative parenting skills decreased following treatment. This result highlights that the CALM program can be effective for reducing maternal and child anxiety.

The mother’s behavior can prepare the child to learn coping skills or be exposed to further problems (Brumariu & Kerns, 2015). Accordingly, Brumariu and Kerns (2015) found a relationship between the emotions of mothers and children and the onset of anxiety symptoms. The mothers of more anxious children provide less attention, love, and affection for their children and talk less to the child when something goes wrong. Additionally, more anxious mothers express less affection and love to their children; they are less likely to engage in conversations with the child when encountering a problem. Moreover, more anxious children are less likely to talk to others. Finally, they demonstrated that the type of behavior and emotions of anxious mothers present a reciprocal effect on their children’s anxiety. Furthermore, the CALM program familiars parents with the basic concepts of support and adjustment (Brumariu & Kerns, 2015). Lebowitz et al. (2020) argued that the SPACE program is highly appropriate for reducing anxiety in children. This program helps mothers and children by involving parents in the treatment process (Lebowitz et al., 2020). However, in another study, they identified no difference between the SPACE program and the cognitive-behavioral therapy, where both approaches were effective (Lebowitz et al., 2020). Furthermore, both programs were effective in reducing rumination in mothers. Ruminants focus on the content of thoughts and self-criticism. Self-Criticism and rumination are incompatible psychological processes that adversely affect parenting and increase parental stress (Lebowitz et al., 2020). Moreira and Canavarro (2018) studied the effects of rumination on parental stress and mindful parenting dimensions, including careful listening; compassion for the child; non-judgmental acceptance of parental performance; child’s emotional awareness, and ER in parents. The relevant results indicated that rumination was reversely associated with all aspects of mindful parenting dimensions and parental stress (Moreira & Canavarro, 2018). Generally, programs developed to inform and educate mothers can help reduce children’s behavioral problems. They are also effective in reducing parenting stress (Khodabakhshi Koolaee et al. 2015). Moreover, a short video tutorial for avoidant parents who had difficulty in effective communication with their child reduced their problematic communication and avoidance behaviors (Ewing et al., 2020). Jamali and Kolabakhshi-Koolaee concluded that the parenting behavior management training program reduces aggression and disobedience in boys (Jamali & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, 2019).

Overall, the CALM and SPACE programs were effective in reducing anxiety and rumination symptoms in the examined mothers. However, the CALM program was more effective in reducing anxiety symptoms than the SPACE program. The CALM program further emphasis on parent-child interactions (Harcourt, Jaseperse & Green 2014; Lebowitz & Shimshoni 2018). Besides, the CALM program provides the parent the power to coach and supervise during the session and enjoys a more suitable feedback system; therefore, it can help improve the parent-child relationship and parenting skills (Comer et al., 2012).

The research sample was limited to the mothers of male primary school students in Sepehr-e Marefat Educational Complex, district 4 of Tehran, i.e., a study limitation.

5. Conclusion

The obtained results revealed that the mothers of bullying children experience high levels of anxiety and rumination. Therefore, parenting education programs, such as CALM and SPACE can improve mothers’ awareness and parenting skills. These programs also reduce their rumination and anxiety. Parents are at the forefront of identifying, preventing, and helping the treatment of their children’s bullying behavior; thus, applying parent training programs can play an effective role in reducing mothers’ and their children’s psychological problems. The school counselors, mental health professionals, psychiatric nurses, and school health nurses are suggested to apply the collected findings.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tehran North Branch, Islamic Azad University, (Code: IR.IAU.TNB.REC.1399.006). All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD. dissertation of the first author at the Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tehran North Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the mothers and the staff and managers of Sepehr-e Marefat Educational Complex who contributed to this research.

References

Akbari Balootbangan, A. & Talepasand, S., 2015. Validation of the Illinois bullying scale in primary school students of Semnan, Iran. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health, 17(4), pp. 178-85. [DOI:10.22038/JFMH.2015.4507]

Bandi, S., 2019. Using the Coaching Approach Behavior and Leading by Modeling (CALM) program to examine attachment and parental behaviors in childhood anxiety [PhD. dissertation]. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University. https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1798/

Benatov, J., 2019. Parent’s feelings, coping strategies, and sense of parental self-efficacy when dealing with children’s victimization experiences. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, p. 700 [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00700] [PMID] [PMCID]

Brumariu, L. E. & Kerns, K. A., 2015. Mother-child emotion communication and childhood anxiety symptoms. Cognition and Emotion, 29(3), pp. 416-31. [DOI:10.1080/02699931.2014.917070] [PMID]

Bui, E., Charney, M. E. & Baker, A. W., 2020. Clinical handbook of anxiety disorders: From theory to parctice. Berlin: Springer [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-30687-8]

Chen, X., et al. 2017. The impact of neuroticism on symptoms of anxiety and depression in elderly adults: The mediating role of rumination. Current Psychology, 39(6), pp. 42-50. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-017-9740-3]

Comer, J. S., et al. 2012. A pilot feasibility evaluation of the CALM Program for anxiety disorders in early childhood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(1), pp. 40-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.08.011] [PMID] [PMCID]

Cooper-Vince, C. E., et al. 2016. Video teleconferencing early child anxiety treatment: A case study of the Internet- Delivered PCIT - CALM (I- CALM) Program. Evidenced-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 1(1), pp. 24-39. [DOI:10.1080/23794925.2016.1191976] [PMID] [PMCID]

Dawoud, S., 2020. Bullying, resilience, and victimization: An investigation among special needs high school students [MA.thesis]. Montclair: Montclair State University. https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/etd/325/

de Vries, E. E., et al. 2017. Like father, like child: Early life family adversity and children’s bullying behaviors in elementary school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(7), pp. 1481-96. [DOI:10.1007/s10802-017-0380-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

Espelage, D. L. & Holt, M. K., 2001. Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 2(2-3), pp. 123-42. [DOI:10.1300/J135v02n02_08]

Feldhaus, C. G., et al. 2020. Rumination - focused cognitive behavioral therapy decreases anxiety and increases behavioral activation among remitted adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), pp. 1982-91. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-020-01711-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

Ewing, D., et al. (2020). Helping parents to help children overcome fear: The influence of a short video tutorial. British Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 80-95. [DOI:10.1111/bjc.12233]

Garcia, I. & O’Neil, J., 2020. Anxiety in adolescents. The Journal of Nurse Practitioners, 17(1), pp. 49-53. [DOI:10.7326/M20-0580]

Gregory, K. D., et al. 2020. Screening for anxiety in adolescent and adult women: A recommendation from the women's preventive services initiative. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(1), pp. 48-56. [DOI:10.7326/M20-0580] [PMID]

Grief Green, J., et al. 2020. Engaging professional sports to reduce bullying: An evaluation of the Boston Vs. Bullies program. Journal of School Violence, 19(3), pp. 389-405. [DOI:10.1080/15388220.2019.1709849]

Harcourt, S., Jaseperse, M. & Green, V. A., 2014. We are sad and we are angry: A systematic review of parents perspectives on bullying. Child and Youth Care, 43(3), pp. 373-91. [DOI:10.1007/s10566-014-9243-4]

Hosseini, S. A. & Rhmadrash, R., 2020. [Study of the effectiveness of anti-bullying training program on the perception of elementary students from school and classroom management (Persian)]. Journal of School Administration, 8(1), pp. 115-35. [DOI:10.34785/J010.2020.712]

Huang, Y., et al. 2019. A meta-analytic review of school-based anti-bullying programs with a parent component. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1(5), pp. 32-44. [DOI:10.1007/s42380-018-0002-1]

Jamali, Z. & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., 2019. [The effectiveness of parenting behavior management training via cell phone on mothers in reducing oppositional and aggression symptoms in their children with oppositional defiant disorder: A single case study (Persian)]. Journal of Arak University of Medical Sciences, 22(4), pp. 134-45. [DOI:10.32598/JAMS.22.4.120]

Kaminetsky, A. G., 2020. The effect of PCIT-CALM on child and parent anxiety and parenting behaviors. New York: Hofstra University. https://www.proquest.com/openview/aab429b1f82e33fe39b2f821f499207a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Karats, H. & Ozturk, C., 2020. Examining the effect of a program developed to address bullying in primary schools. Journal of Pediatric Research, 7(3), pp. 243-9. [DOI:10.4274/jpr.galenos.2019.37929]

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A. & Darestani-Farahani, F., 2020. Coloring mandala as jungian art to reduce bullying and increase social skills. Journal of Client-centered Nursing Care, 6(3), pp. 193-202. [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.6.3.33.11]

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., et al. 2015. [The effect of positive parenting program training in mothers of children with attention deficit hyperactivity on reducing children’s externalizing behavior problems (Persian)]. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health, 17(3), pp. 135-41. [DOI:10.22038/JFMH.2015.4312]

Lebowitz, E. R., 2013. Parent-based treatment for childhood and adolescent OCD. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 2(4), pp. 425-31. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocrd.2013.08.004]

Lebowitz, E. R., et al. 2014. Parent Training for childhood anxiety disorder: The space program. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 21(4), pp. 456-69. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.10.004]

Lebowitz, E. R. & Shimshoni, Y., 2018. The SPACE program, a parent-based treatment for childhood and adolescent OCD: The case of Jasmine. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 82(4), pp. 266-87. [DOI:10.1521/bumc.2018.82.4.266] [PMID]

Lebowitz, E. R., et al. 2020. Parent-based treatment as efficacious as cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety: A randomized noninferiority study of supportive parenting for anxious childhood emotions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(3), pp. 362-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.02.014] [PMID] [PMCID]

Mansouri. A., et al. 2012. [The comparison of worry, obsession and rumination in individual with generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depression disorder and normal individual (Persian). Quarterly Journal of Psychological Studies, 7(4), pp. 55-74. [DOI:10.22051/PSY.2011.1535]

Moreira, H. & Canavarro, M. C., 2018. The association between self-critical rumination and parenting stress: The mediating role of mindful parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(7), pp. 2265-75. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-018-1072-x]

Muhopliah, P., Tentama, F. & Yuzarion, Y., 2020. Bullying scale: A psychometric study for bullying perpetrators in junior high school. European Journal of Education Studies, 7(7), pp. 92-106. [DOI:10.46827/ejes.v7i7.3158]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. & Morrow, J., 1991. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 61(1), pp. 115-21. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115] [PMID]

Olweus, D., Solberg, M. E. & Breivik, K., 2020. Long‐term school‐level effects of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP). Scandinavian Journal Of Psychology, 61(1), pp. 108-16. [DOI:10.1111/sjop.12486] [PMID]

Pang, Z., Tu, D. & Cai, Y., 2019. Psychometric properties of the S.A.S., B.A.I, and S-AI in Chinese University Students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, p. 93. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00093] [PMID] [PMCID]

Puliafico, A. C., Comer, J. S. & Albano, A. M., 2013. Coaching approach behavior and leading by modeling: Rational, principles, and a session- by-session description of the calm program for early childhood anxiety. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(4), pp. 517-28. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.05.002]

Setyowati, A., Chung, M. & Yusuf, A., 2019. Development of self-report assessment tool for anxiety among adolescence: Indonesian version of rating anxiety scale. Journal of Public Health in Africa, 10(s1), pp. 15-8. [DOI:10.4081/jphia.2019.1172]

Thomas Cook, D., 2020. The SAGE encyclopedia of children and childhood studies. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. https://books.google.com/books?id=KxHADwAAQBAJ&dq

Valle, J. E., Williams, L. C. A. & Stelko-pereira, A. C., 2020. Whole-school untibullying interventio ns: A systematic review of 20 years of publications. Psychology in the Schools, 57(6), pp. 868-83. [DOI:10.1002/pits.22377]

van Niejenhuis, C., Huitsing, G. & Veenstra, R., 2020. Working with parents to counteract bullying: A randomized controlled trial of an intervention to improve parent-school cooperation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(1), pp. 117-31. [DOI:10.1111/sjop.12522] [PMID] [PMCID]

Zung, W. W. K., 1971. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics, 12(6), pp. 371-9. [DOI:10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0]

Bandi, S., 2019. Using the Coaching Approach Behavior and Leading by Modeling (CALM) program to examine attachment and parental behaviors in childhood anxiety [PhD. dissertation]. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University. https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1798/

Benatov, J., 2019. Parent’s feelings, coping strategies, and sense of parental self-efficacy when dealing with children’s victimization experiences. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, p. 700 [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00700] [PMID] [PMCID]

Brumariu, L. E. & Kerns, K. A., 2015. Mother-child emotion communication and childhood anxiety symptoms. Cognition and Emotion, 29(3), pp. 416-31. [DOI:10.1080/02699931.2014.917070] [PMID]

Bui, E., Charney, M. E. & Baker, A. W., 2020. Clinical handbook of anxiety disorders: From theory to parctice. Berlin: Springer [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-30687-8]

Chen, X., et al. 2017. The impact of neuroticism on symptoms of anxiety and depression in elderly adults: The mediating role of rumination. Current Psychology, 39(6), pp. 42-50. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-017-9740-3]

Comer, J. S., et al. 2012. A pilot feasibility evaluation of the CALM Program for anxiety disorders in early childhood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(1), pp. 40-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.08.011] [PMID] [PMCID]

Cooper-Vince, C. E., et al. 2016. Video teleconferencing early child anxiety treatment: A case study of the Internet- Delivered PCIT - CALM (I- CALM) Program. Evidenced-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 1(1), pp. 24-39. [DOI:10.1080/23794925.2016.1191976] [PMID] [PMCID]

Dawoud, S., 2020. Bullying, resilience, and victimization: An investigation among special needs high school students [MA.thesis]. Montclair: Montclair State University. https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/etd/325/

de Vries, E. E., et al. 2017. Like father, like child: Early life family adversity and children’s bullying behaviors in elementary school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(7), pp. 1481-96. [DOI:10.1007/s10802-017-0380-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

Espelage, D. L. & Holt, M. K., 2001. Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 2(2-3), pp. 123-42. [DOI:10.1300/J135v02n02_08]

Feldhaus, C. G., et al. 2020. Rumination - focused cognitive behavioral therapy decreases anxiety and increases behavioral activation among remitted adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), pp. 1982-91. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-020-01711-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

Ewing, D., et al. (2020). Helping parents to help children overcome fear: The influence of a short video tutorial. British Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 80-95. [DOI:10.1111/bjc.12233]

Garcia, I. & O’Neil, J., 2020. Anxiety in adolescents. The Journal of Nurse Practitioners, 17(1), pp. 49-53. [DOI:10.7326/M20-0580]

Gregory, K. D., et al. 2020. Screening for anxiety in adolescent and adult women: A recommendation from the women's preventive services initiative. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(1), pp. 48-56. [DOI:10.7326/M20-0580] [PMID]

Grief Green, J., et al. 2020. Engaging professional sports to reduce bullying: An evaluation of the Boston Vs. Bullies program. Journal of School Violence, 19(3), pp. 389-405. [DOI:10.1080/15388220.2019.1709849]

Harcourt, S., Jaseperse, M. & Green, V. A., 2014. We are sad and we are angry: A systematic review of parents perspectives on bullying. Child and Youth Care, 43(3), pp. 373-91. [DOI:10.1007/s10566-014-9243-4]

Hosseini, S. A. & Rhmadrash, R., 2020. [Study of the effectiveness of anti-bullying training program on the perception of elementary students from school and classroom management (Persian)]. Journal of School Administration, 8(1), pp. 115-35. [DOI:10.34785/J010.2020.712]

Huang, Y., et al. 2019. A meta-analytic review of school-based anti-bullying programs with a parent component. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1(5), pp. 32-44. [DOI:10.1007/s42380-018-0002-1]

Jamali, Z. & Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., 2019. [The effectiveness of parenting behavior management training via cell phone on mothers in reducing oppositional and aggression symptoms in their children with oppositional defiant disorder: A single case study (Persian)]. Journal of Arak University of Medical Sciences, 22(4), pp. 134-45. [DOI:10.32598/JAMS.22.4.120]

Kaminetsky, A. G., 2020. The effect of PCIT-CALM on child and parent anxiety and parenting behaviors. New York: Hofstra University. https://www.proquest.com/openview/aab429b1f82e33fe39b2f821f499207a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Karats, H. & Ozturk, C., 2020. Examining the effect of a program developed to address bullying in primary schools. Journal of Pediatric Research, 7(3), pp. 243-9. [DOI:10.4274/jpr.galenos.2019.37929]

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A. & Darestani-Farahani, F., 2020. Coloring mandala as jungian art to reduce bullying and increase social skills. Journal of Client-centered Nursing Care, 6(3), pp. 193-202. [DOI:10.32598/JCCNC.6.3.33.11]

Khodabakhshi-Koolaee, A., et al. 2015. [The effect of positive parenting program training in mothers of children with attention deficit hyperactivity on reducing children’s externalizing behavior problems (Persian)]. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health, 17(3), pp. 135-41. [DOI:10.22038/JFMH.2015.4312]

Lebowitz, E. R., 2013. Parent-based treatment for childhood and adolescent OCD. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 2(4), pp. 425-31. [DOI:10.1016/j.jocrd.2013.08.004]

Lebowitz, E. R., et al. 2014. Parent Training for childhood anxiety disorder: The space program. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 21(4), pp. 456-69. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.10.004]

Lebowitz, E. R. & Shimshoni, Y., 2018. The SPACE program, a parent-based treatment for childhood and adolescent OCD: The case of Jasmine. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 82(4), pp. 266-87. [DOI:10.1521/bumc.2018.82.4.266] [PMID]

Lebowitz, E. R., et al. 2020. Parent-based treatment as efficacious as cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety: A randomized noninferiority study of supportive parenting for anxious childhood emotions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(3), pp. 362-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.02.014] [PMID] [PMCID]

Mansouri. A., et al. 2012. [The comparison of worry, obsession and rumination in individual with generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depression disorder and normal individual (Persian). Quarterly Journal of Psychological Studies, 7(4), pp. 55-74. [DOI:10.22051/PSY.2011.1535]

Moreira, H. & Canavarro, M. C., 2018. The association between self-critical rumination and parenting stress: The mediating role of mindful parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(7), pp. 2265-75. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-018-1072-x]

Muhopliah, P., Tentama, F. & Yuzarion, Y., 2020. Bullying scale: A psychometric study for bullying perpetrators in junior high school. European Journal of Education Studies, 7(7), pp. 92-106. [DOI:10.46827/ejes.v7i7.3158]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. & Morrow, J., 1991. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 61(1), pp. 115-21. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115] [PMID]

Olweus, D., Solberg, M. E. & Breivik, K., 2020. Long‐term school‐level effects of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP). Scandinavian Journal Of Psychology, 61(1), pp. 108-16. [DOI:10.1111/sjop.12486] [PMID]

Pang, Z., Tu, D. & Cai, Y., 2019. Psychometric properties of the S.A.S., B.A.I, and S-AI in Chinese University Students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, p. 93. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00093] [PMID] [PMCID]

Puliafico, A. C., Comer, J. S. & Albano, A. M., 2013. Coaching approach behavior and leading by modeling: Rational, principles, and a session- by-session description of the calm program for early childhood anxiety. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(4), pp. 517-28. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.05.002]

Setyowati, A., Chung, M. & Yusuf, A., 2019. Development of self-report assessment tool for anxiety among adolescence: Indonesian version of rating anxiety scale. Journal of Public Health in Africa, 10(s1), pp. 15-8. [DOI:10.4081/jphia.2019.1172]

Thomas Cook, D., 2020. The SAGE encyclopedia of children and childhood studies. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. https://books.google.com/books?id=KxHADwAAQBAJ&dq

Valle, J. E., Williams, L. C. A. & Stelko-pereira, A. C., 2020. Whole-school untibullying interventio ns: A systematic review of 20 years of publications. Psychology in the Schools, 57(6), pp. 868-83. [DOI:10.1002/pits.22377]

van Niejenhuis, C., Huitsing, G. & Veenstra, R., 2020. Working with parents to counteract bullying: A randomized controlled trial of an intervention to improve parent-school cooperation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(1), pp. 117-31. [DOI:10.1111/sjop.12522] [PMID] [PMCID]

Zung, W. W. K., 1971. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics, 12(6), pp. 371-9. [DOI:10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2020/12/26 | Accepted: 2021/02/1 | Published: 2021/05/1

Received: 2020/12/26 | Accepted: 2021/02/1 | Published: 2021/05/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |