Fri, Jul 4, 2025

[Archive]

Volume 11, Issue 1 (Winter 2025)

JCCNC 2025, 11(1): 35-44 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rashvand F, Safari Alamuti F, Shahsavari N, Momeni M. Investigating the Predictive Role of Disability and Comorbidity in the Sleep Quality of Hospitalized Older Adults. JCCNC 2025; 11 (1) :35-44

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-616-en.html

URL: http://jccnc.iums.ac.ir/article-1-616-en.html

1- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Research Institute for Prevention of Non-Communicable Diseases, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran.

2- Student Research Committee, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran.

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Research Institute for Prevention of Non-Communicable Diseases, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran. ,momeni65@gmail.com

2- Student Research Committee, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran.

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Research Institute for Prevention of Non-Communicable Diseases, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 622 kb]

(384 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1105 Views)

Full-Text: (157 Views)

Introduction

Since the beginning of the 21st century, aging has become a growing global problem. Nowadays the physical and mental health of older adults is one of the public health priorities (Yue et al., 2022). Along with the increase in the elderly population, various disorders, such as dementia, depression, and sleep disorders create many challenges for healthcare systems, among which sleep disorders are more important (Suzuki et al., 2017).

Sleep quality is one of the important aspects affecting the quality of life (QoL) in older adults (Hu et al., 2022). Poor sleep quality is a common complaint in older adults. Almost 50% of the older persons report poor sleep quality. It is often overlooked compared to other common health issues because most older adults consider it as part of the natural aging process (Chiang et al., 2018). The hospitalized older adults may experience a poor quality of sleep due to one or more diseases, diseases-associated disability, and environmental changes. The factors that affect the sleep quality of hospitalized older adults are more complex and multifaceted, including the type of ward, the use of sleep-inducing drugs, the length of stay in the hospital, the severity of pain, and suffering from several chronic diseases (Chung et al., 2023).

Among the health-related factors, comorbidities are common in older adults. Comorbidities may destroy the sleep quality of older adults due to the physical and mental burden caused by their worries about their health status (Song et al., 2020). Some recent studies indicated the relationship between suffering from chronic diseases and comorbidity with sleep quality among older adults (Idalino et al., 2023; Muhammad et al., 2023). However, there are discrepancies regarding the relationship between comorbidities and sleep quality in older adults. In some previous studies, comorbidity has not been identified as a predictor of sleep quality among community-dwelling older adults (Aliabadi et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2022).

In recent decades, the issue of disability in older adults has received considerable attention (Luo et al., 2024). In the aging process, the decrease in muscle strength and functional capacity causes weakness, which ultimately leads to disability. Physical disability is defined as the inability to independently perform essential activities of daily living (Chien & Chen, 2015). A previous study reported that sleep quality can have more destructive effects on the daily activities of older adults with disabilities (Mayfield et al., 2023). Also, the results of a previous study indicated that older adults with more disability have reported more insomnia. However, this study was limited to community-dowelling older men (Arakaki et al., 2022). In another study, various comorbidities, such as musculoskeletal disorders and depression were reported as the main cause of disability among community-dwelling older adults in Iran (Vafaei et al., 2014). In contrast, another study involving Iranian community-dwelling older adults showed that poor sleep quality was not associated with dependence in performing daily activities (Aliabadi et al., 2017).

Considering the increasing importance and complexity of the concept of sleep quality, it is important to understand its predictors, especially in older adults. Most previous studies have been conducted among community-dwelling healthy older adults living in Western countries, whereas, individual, lifestyle, and medical factors associated with sleep disorders may vary by ethnicity and culture (Wang et al., 2020). Also, hospitalization can significantly reduce the sleep quality of older adults. It is important to conduct more studies to identify the main factors affecting the sleep quality of hospitalized older adults. To date, limited studies have been conducted to reveal whether the increase in comorbidities and their related disabilities are associated with poor sleep quality among inpatient older adults. Hence, the present study aimed to determine the predictive role of disability and comorbidities in the sleep quality of hospitalized older adults.

Materials and Methods

Study design, setting, and sample

A cross-sectional, correlational design was utilized to perform the study. A total of 300 hospitalized older adults were recruited in the study by convenience sampling from the medical-surgical departments of three major teaching hospitals of Qazvin Province, Iran, in 2023. The inclusion criteria were consent to participate in the study, 60 years of age and older, the ability to communicate verbally, not cognitively impaired, hospitalization only for the diagnosis or treatment of internal diseases, and having a discharge order before sampling. Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria were hospitalization in critical care units, acute stroke, amputation, having surgery, inability to walk, and use of drugs effective on sleep disorders such as antidepressants, antihistamines, and benzodiazepines.

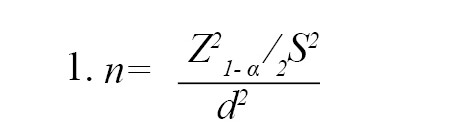

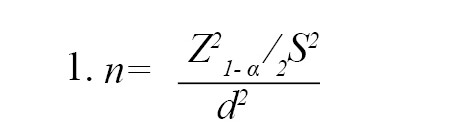

The sample size was calculated based on the study of Davoudi Boroujerdi et al. (2020), in which the sample size was reported considering the Mean±SD of the sleep quality of the elderly equal to 8.29±3.36 and power=0.8, α=0.05, and accuracy 0.543 using the Equation 1. The calculated sample size was 300 people according to the objectives of the current research.

Sampling was done every day of the week. The researcher completed the questionnaires through face-to-face interviews with the older adults.

Study instruments

The data were collected using a four-part questionnaire.

Demographic and clinical characteristics form

The demographic and clinical characteristic form consisted of age, gender, marital status, education, employment, smoking and non-opioid analgesic use, duration of hospitalization, and comorbidities.

The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)

The CCI includes 17 medical conditions, which are scored as 1, 2, 3 and 6 based on the severity of the disease as well as the risk of mortality. The score of each medical condition is as follows: Myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attracts, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, and peptic ulcer disease as (yes=1, no=0), liver disease (none=0, mild=1, moderate to severe=3), diabetes mellitus (none/ diet-controlled=0, uncomplicated=1, end organ damage=2), hemiplegia (yes=2, no=0), lymphoma (yes=2, no=0), AIDS (yes=6, no=0). Also, due to the correlation between age and survival, the age variable is considered in the calculation of the disease burden score, so that the final score is calculated by adding 1 point for each decade over 40 years (50 to 59 years [+1], 60-69 years [+2], 70-79 years [+3],≥80 years [+4]). The total score of the CCI is a simple sum of the points, with higher scores indicating more severe comorbid conditions (Charlson et al., 1994). The validity and reliability of the index have been proven in Iranian older adults (Cronbach α=0.77) (Hosseini et al., 2020).

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

The PSQI is a self-report valid and reliable 19-item index that assesses sleep quality over the past month and examines the following 7 components: Subjective sleep quality, latency, duration, efficiency, disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Its questions are scored based on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty). The overall components’ scores range from 0 to 21, with a score >5 indicating poor sleep quality, and ≤5 indicating good sleep quality (Buysse et al., 1989). The validity and reliability of the questionnaire have been proven in Iranian elderly (Farrahi Moghaddam et al., 2012; Chehri et al., 2020).

World Health Organization (WHO) disability assessment schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0)

The WHODAS 2.0 was used to measure disability levels in older adults. This instrument has 36 items that encompass the six following domains: 1) Cognition (understanding and communicating; 6 items), 2) Mobility (moving and getting around; 5 items), 3) Self-care (hygiene, dressing, eating, and being around people; 4 items), 4) Getting along (interacting with people; 5 items), 5) Life activities (domestic responsibilities, leisure, work, and school; 8 items), and 6) Participation (joining in community activities and participating in society; 8 items). The WHODAS 2.0 uses a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from 0 (no difficulty) to 4 (extreme difficulty or total inability). At first, the sum of items’ scores in each domain was determined and then the sum of the scores of all 6 domains was calculated. Finally, the total scores were converted to 0-100 (0=no disability and 100=complete disability). In other words, lower scores represent less disability (Üstün, 2010). The psychometric properties of the Persian version of the questionnaire have been proven (Salehi et al., 2020; Rajeziesfahani et al., 2019). In the present study, the reliability of the WHODAS 2.0 and PSQI were examined using the Cronbach α on 20 hospitalized older adults, and the Cronbach α was 0.78 and 0.85, respectively. These 20 samples were excluded from the final data analysis.

Data analysis

All of the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software, version 26. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and histogram plots were used to test the normality of the data. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and evaluated with chi-square or Fisher exact test. Continuous data were presented as Mean±SD and were compared using the two-sample independent t-test. A binary logistic regression test was used to determine the predictors of sleep quality. Statistically significant variables in univariate analysis were included in the regression model. The statistical significance level was considered at P<0.05.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics, sleep quality, and disability

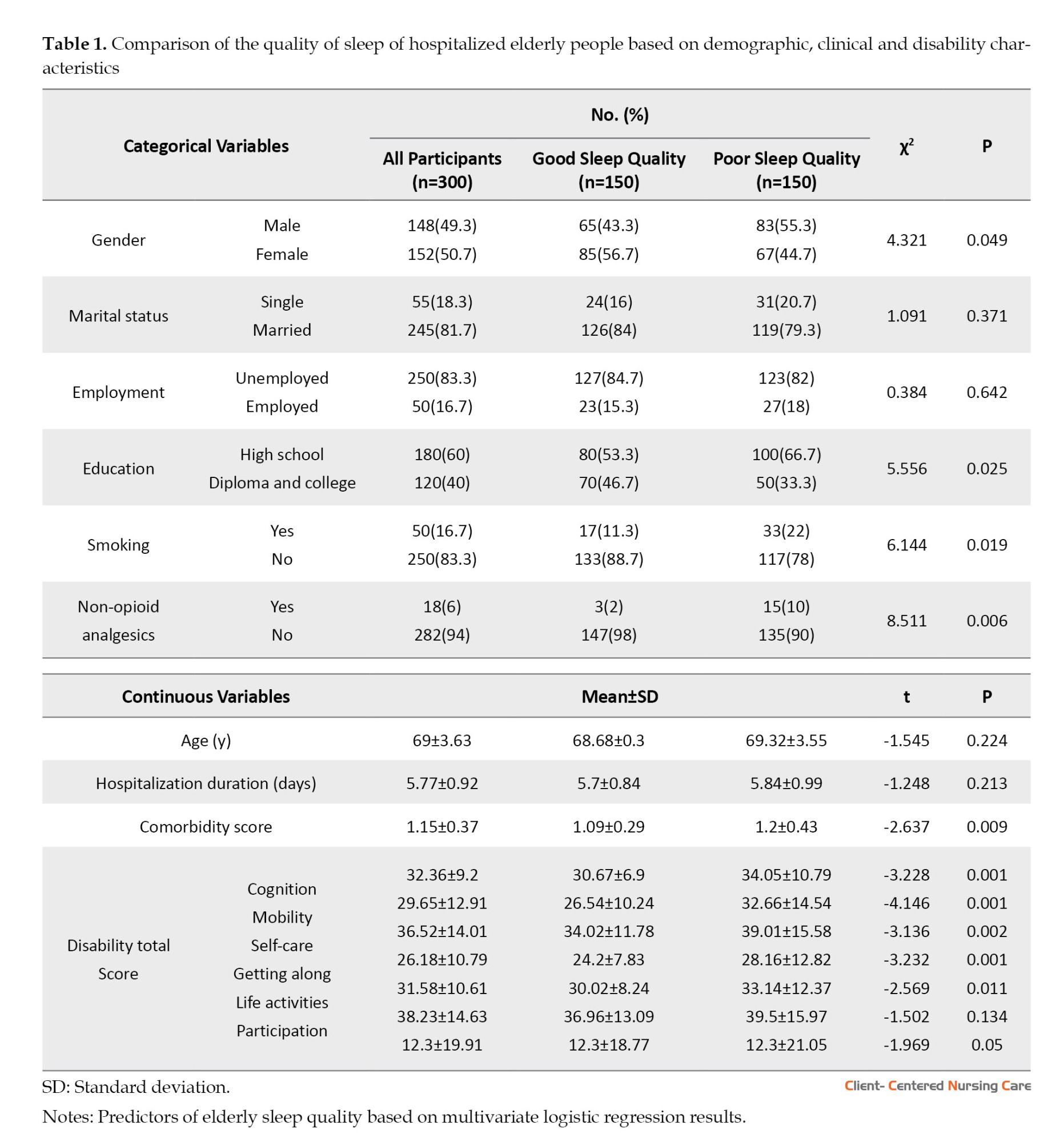

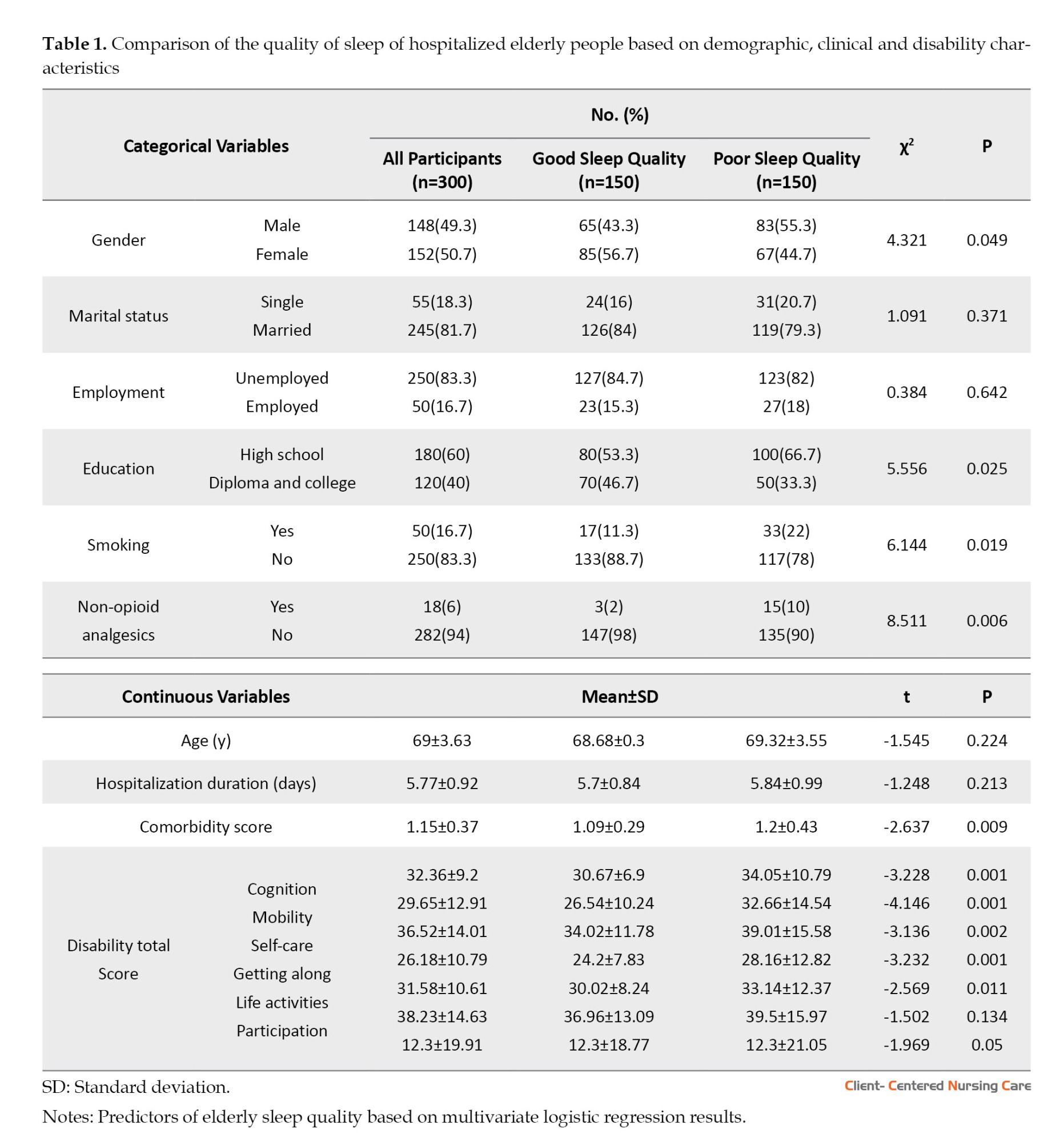

The Mean±SD age of the participants was 69±3.63 years, and the majority of them (50.7%) were women, married (81.7%), unemployed (83.3%), and had high school education (60%). The Mean±SD total disability score was 32.36±9.2. The Mean±SD PSQI score was 6.12±2.99 and 50% of the older adults had poor sleep quality (PSQI >5). The highest disability score of the elderly was reported in the life activities domain (38.23±14.63) and the lowest disability score was reported in the participation domain (12.3±19.91). Of the 300 elderly examined, 43(14.3%) had mild disability, 240(80%) had moderate disability, and 17(5.6%) had severe/very severe disability. The Mean±SD burden of comorbidities was 1.15 (0.37) (Table 1).

Univariate analysis results

In univariate analysis, there was a significant relationship between sleep quality and gender, education, smoking, drug use, co-morbidities, and disability. Male gender (P<0.049), lower education (P<0.025), smoking (P<0.019), non-opioid analgesics (P<0.006), more comorbidities (P<0.009), and higher disability scores (P<0.001) were associated with poor sleep quality. No significant relationship was found between age, marital status, employment, duration of hospitalization, and sleep quality (Table 1).

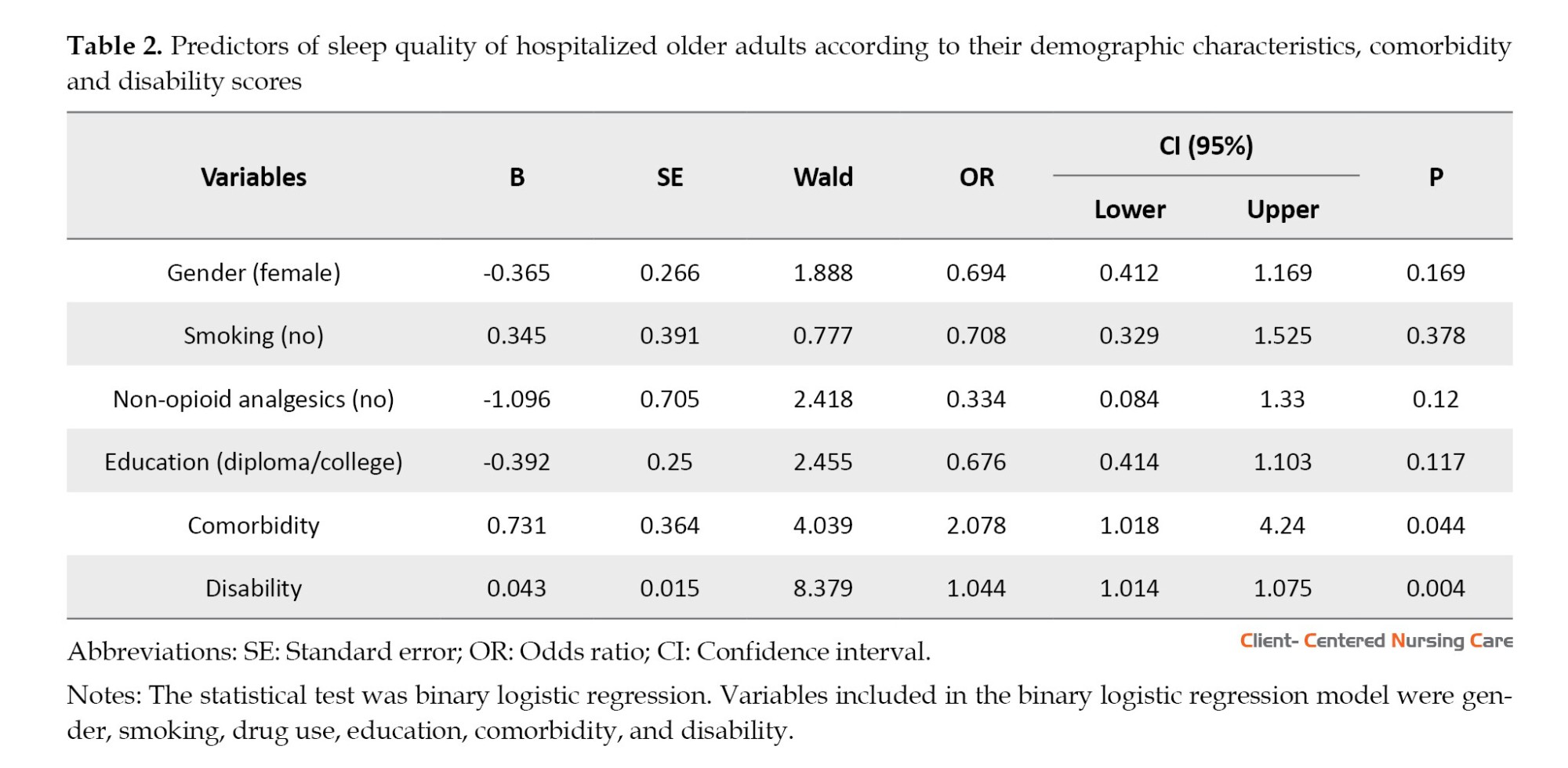

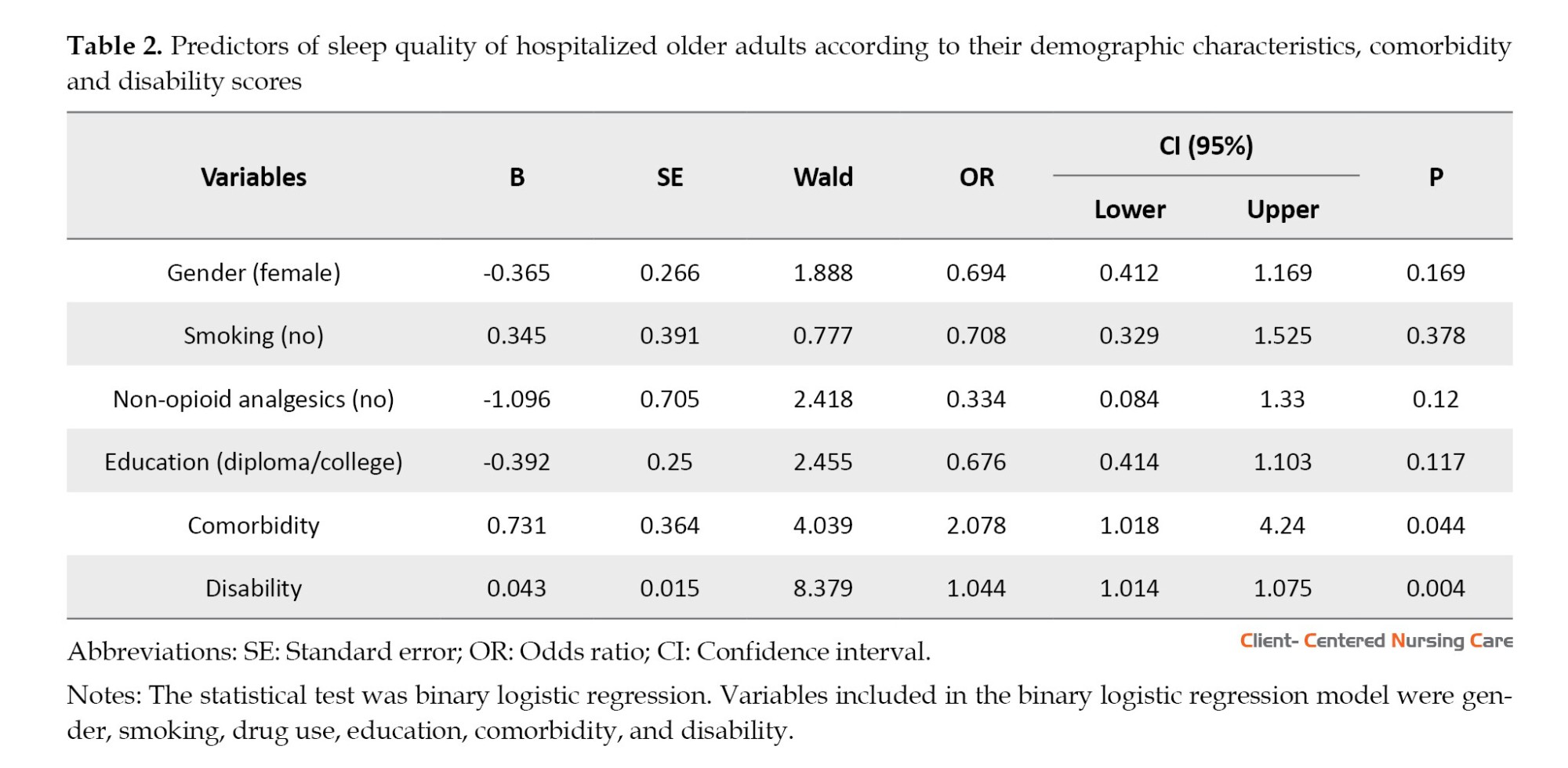

In the multivariate analysis, there was a statistically significant relationship between the burden of comorbidity and the level of disability with poor sleep quality. Accordingly, more burden of comorbidity increased the chance of experiencing poor sleep quality in older adults to the extent of 2.078 times (odd ratio [OR]=2.078, P<0.044). Also, a higher disability score increased the chance of experiencing poor sleep quality in older adults to the extent of 1.044 (P<0.004, OR=1.044; Table 2). Contrary to univariate analysis (Table 1), in the multiple regression model, no significant relationship was found between gender, education, smoking, non-opioid analgesics, and sleep quality of hospitalized older patients (Table 2).

Discussion

Sleep quality is an important issue in hospitalized older people and is affected by several factors. The current study determined the predictive role of disability and comorbidities in the sleep quality of hospitalized elderly patients.

The findings of the present study showed that half of the hospitalized older adults have suffered from poor sleep quality which is in line with the results of Papi et al.’s study on older adults in daycare centers (Papi et al., 2019). A systematic review study also reported that (70%) of Iranian older adults did not have desirable sleep quality (Mortazavi et al., 2021). Contrary to the present study results, Zhang et al. (2020) reported that only (21%) of the older adults suffered from poor sleep quality. They attributed the low prevalence to the definition of poor sleep quality in their study (PSQI >7 vs PSQI >5 recommended by the PSQI developer).

People who are admitted to the hospital usually suffer from disorders such as daytime sleepiness, sleep-wake cycle disruption, and changes in the amount of melatonin hormone secretion due to being confined to bed. Also, hospitalization can be associated with poor sleep quality and reduced sleep duration due to various diseases, stressful conditions, or changes in the sleeping environment (Kulpatcharapong et al., 2020).

In this study, the comorbidities positively predicted poor sleep quality among inpatient older adults which was consistent with the findings of earlier research (Idalino et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2020; Chung et al., 2023; Muhammad et al., 2023). Comorbidities can lead to problems such as insomnia, reduced sleep duration, difficulty breathing during sleep, snoring, and restless legs. These conditions may affect the quality of sleep and cause sleepiness during the day (Appleton et al., 2018). Some chronic diseases may cause changes in the brain regions and neurotransmitters that control sleep. Also, the drugs used to manage comorbidities affect sleep quality (Muhammad et al., 2023). Psychological distress and anxiety associated with comorbidities, including economic burden (Larkin et al., 2021), destructive effects on family relationships and social interactions, and experiencing more negative and stressful life events can lead to the development and exacerbation of sleep problems (Ren et al., 2021; Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al., 2021; Muhammad et al., 2023). On the other hand, Idalino et al. showed that elderly people with sleep problems had a higher chance of developing chronic conditions. They stated that there may be a bidirectional relationship between chronic conditions and sleep quality (Idalino et al., 2023). In contrast to the current study, a prior study showed that there has been no relationship between comorbidities and sleep quality in hospitalized elderly people (Kulpatcharapong et al., 2020). Therefore, early identification and optimizing the management of comorbidities, especially by implementing non-pharmacological interventions, awareness of side effects of medications that aggravate sleep problems, and emphasis on safe nursing care in hospitalized older adults seem necessary to improve the sleep quality of this group (Mc Carthy, 2021; Rashvand et al., 2016).

A previous study suggests that multiple comorbidities and clinical conditions are key elements that should be addressed in the relationship between sleep quality and disability in older adults (Oliveira et al., 2022). In the present study, the highest level of disability was related to the domains of life activities and mobility, and the lowest level of disability was related to the participation domain. In a previous study, the highest level of disability was reported in the domains of life activities and mobility, and the lowest level of disability was related to the self-care domain (Adib-Hajbaghery & Akbari, 2009). In another study, the highest level of disability was reported in the domain of interacting with people and mobility (Ghasemi et al., 2022). The discrepancy in the findings of the studies can be attributed to the differences between the questionnaires, the study setting, and the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

Moreover, our research found a significant positive relationship between disability and sleep quality in inpatient older adults. This finding was similar to the previous studies (Arakaki et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2022; Chien & Chen, 2015). In support of the present study, Mazzotti et al. found that higher levels of disability in older adults have reduced sleep quality and ability to perform daily activities (Mazzotti et al., 2012). Older persons with poor sleep quality suffer fatigue, sleepiness, and lack of concentration during the day. This may reduce their ability to perform life activities (Safa et al., 2015). A prior study reported that older adults with a healthier aging process were able to create more regularity in their sleep patterns, which may have a positive effect on their physical ability (Friedman et al., 2019). Yang et al. suggested that there may be a bidirectional causal relationship between disability and sleep quality in the elderly. Poor sleep quality may hurt physical performance by causing mental fatigue. Also, older persons with moderate and severe disabilities stay longer in bed, which can increase sleep duration and impair sleep quality (Yang et al., 2023). A review study showed that lack of physical activity affects the quantity and quality of sleep in Iranian older adults. Physical activity increases energy consumption and improves sleep quality by endocrine secretions (Mortazavi et al., 2021). Physical activity relieves stress and is associated with good sleep quality in older adults. Encouraging the elderly to exercise and physical activity helps to improve their sleep quality (Song et al., 2020). Strategies to promote healthy sleep, including regular sleep schedules, exercising, and avoiding excessive use of electronic devices before bed, were considered key elements in improving disability associated with sleep disorders in older adults. A healthy and regular sleep pattern may help reduce the risk of developing or worsening chronic conditions in older adults (Idalino et al., 2023; Aliasgharpoor & Eybpoosh, 2011).

Conclusion

The present study added to the existing knowledge regarding the predictors of sleep quality in older adults. Half of the hospitalized older adults had poor sleep quality in our study. Comorbidities and disability were the most important predictors of sleep quality in hospitalized older adults. To promote sleep quality, healthcare providers should educate older adults to report different degrees of disability and symptoms of comorbidities immediately. Also, monitoring older adults for comorbidities and disabilities seems necessary. It is essential to design and implement interventional studies to investigate the effect of physical activity and exercise on sleep quality and disability levels among older adults. Moreover, it is important to identify possible mechanisms (mediating factors) of how comorbidities and disabilities are associated with sleep quality in the older population.

Study limitations

The strength of the present study was the multicenter sampling that increased the generalizability of the findings. However, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits the ability to determine causality. It is suggested that future studies be conducted with a longitudinal design to more clearly understand the predictors of sleep quality in hospitalized older adults. Also, self-reported measurement of sleep quality did not allow objective assessment of sleep quality. It is suggested that future studies use objective methods of sleep quality assessment such as polysomnography.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran (Code IR.QUMS.REC.1402.033). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants after explaining the purpose of the study and ensuring confidentiality and anonymity.

Funding

The current article was taken from a research proposal (No.: 401000095) and it was financially supported by Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, statistical analysis, and supervision: Maryam Momeni and Farnoosh Rashvand; Data collection: Fatemeh Safari Alamuti and Neda Shahsavari; Writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude for the cooperation of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, hospital officials, and elderly people participating in the study.

References

Since the beginning of the 21st century, aging has become a growing global problem. Nowadays the physical and mental health of older adults is one of the public health priorities (Yue et al., 2022). Along with the increase in the elderly population, various disorders, such as dementia, depression, and sleep disorders create many challenges for healthcare systems, among which sleep disorders are more important (Suzuki et al., 2017).

Sleep quality is one of the important aspects affecting the quality of life (QoL) in older adults (Hu et al., 2022). Poor sleep quality is a common complaint in older adults. Almost 50% of the older persons report poor sleep quality. It is often overlooked compared to other common health issues because most older adults consider it as part of the natural aging process (Chiang et al., 2018). The hospitalized older adults may experience a poor quality of sleep due to one or more diseases, diseases-associated disability, and environmental changes. The factors that affect the sleep quality of hospitalized older adults are more complex and multifaceted, including the type of ward, the use of sleep-inducing drugs, the length of stay in the hospital, the severity of pain, and suffering from several chronic diseases (Chung et al., 2023).

Among the health-related factors, comorbidities are common in older adults. Comorbidities may destroy the sleep quality of older adults due to the physical and mental burden caused by their worries about their health status (Song et al., 2020). Some recent studies indicated the relationship between suffering from chronic diseases and comorbidity with sleep quality among older adults (Idalino et al., 2023; Muhammad et al., 2023). However, there are discrepancies regarding the relationship between comorbidities and sleep quality in older adults. In some previous studies, comorbidity has not been identified as a predictor of sleep quality among community-dwelling older adults (Aliabadi et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2022).

In recent decades, the issue of disability in older adults has received considerable attention (Luo et al., 2024). In the aging process, the decrease in muscle strength and functional capacity causes weakness, which ultimately leads to disability. Physical disability is defined as the inability to independently perform essential activities of daily living (Chien & Chen, 2015). A previous study reported that sleep quality can have more destructive effects on the daily activities of older adults with disabilities (Mayfield et al., 2023). Also, the results of a previous study indicated that older adults with more disability have reported more insomnia. However, this study was limited to community-dowelling older men (Arakaki et al., 2022). In another study, various comorbidities, such as musculoskeletal disorders and depression were reported as the main cause of disability among community-dwelling older adults in Iran (Vafaei et al., 2014). In contrast, another study involving Iranian community-dwelling older adults showed that poor sleep quality was not associated with dependence in performing daily activities (Aliabadi et al., 2017).

Considering the increasing importance and complexity of the concept of sleep quality, it is important to understand its predictors, especially in older adults. Most previous studies have been conducted among community-dwelling healthy older adults living in Western countries, whereas, individual, lifestyle, and medical factors associated with sleep disorders may vary by ethnicity and culture (Wang et al., 2020). Also, hospitalization can significantly reduce the sleep quality of older adults. It is important to conduct more studies to identify the main factors affecting the sleep quality of hospitalized older adults. To date, limited studies have been conducted to reveal whether the increase in comorbidities and their related disabilities are associated with poor sleep quality among inpatient older adults. Hence, the present study aimed to determine the predictive role of disability and comorbidities in the sleep quality of hospitalized older adults.

Materials and Methods

Study design, setting, and sample

A cross-sectional, correlational design was utilized to perform the study. A total of 300 hospitalized older adults were recruited in the study by convenience sampling from the medical-surgical departments of three major teaching hospitals of Qazvin Province, Iran, in 2023. The inclusion criteria were consent to participate in the study, 60 years of age and older, the ability to communicate verbally, not cognitively impaired, hospitalization only for the diagnosis or treatment of internal diseases, and having a discharge order before sampling. Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria were hospitalization in critical care units, acute stroke, amputation, having surgery, inability to walk, and use of drugs effective on sleep disorders such as antidepressants, antihistamines, and benzodiazepines.

The sample size was calculated based on the study of Davoudi Boroujerdi et al. (2020), in which the sample size was reported considering the Mean±SD of the sleep quality of the elderly equal to 8.29±3.36 and power=0.8, α=0.05, and accuracy 0.543 using the Equation 1. The calculated sample size was 300 people according to the objectives of the current research.

Sampling was done every day of the week. The researcher completed the questionnaires through face-to-face interviews with the older adults.

Study instruments

The data were collected using a four-part questionnaire.

Demographic and clinical characteristics form

The demographic and clinical characteristic form consisted of age, gender, marital status, education, employment, smoking and non-opioid analgesic use, duration of hospitalization, and comorbidities.

The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)

The CCI includes 17 medical conditions, which are scored as 1, 2, 3 and 6 based on the severity of the disease as well as the risk of mortality. The score of each medical condition is as follows: Myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attracts, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, and peptic ulcer disease as (yes=1, no=0), liver disease (none=0, mild=1, moderate to severe=3), diabetes mellitus (none/ diet-controlled=0, uncomplicated=1, end organ damage=2), hemiplegia (yes=2, no=0), lymphoma (yes=2, no=0), AIDS (yes=6, no=0). Also, due to the correlation between age and survival, the age variable is considered in the calculation of the disease burden score, so that the final score is calculated by adding 1 point for each decade over 40 years (50 to 59 years [+1], 60-69 years [+2], 70-79 years [+3],≥80 years [+4]). The total score of the CCI is a simple sum of the points, with higher scores indicating more severe comorbid conditions (Charlson et al., 1994). The validity and reliability of the index have been proven in Iranian older adults (Cronbach α=0.77) (Hosseini et al., 2020).

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

The PSQI is a self-report valid and reliable 19-item index that assesses sleep quality over the past month and examines the following 7 components: Subjective sleep quality, latency, duration, efficiency, disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Its questions are scored based on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty). The overall components’ scores range from 0 to 21, with a score >5 indicating poor sleep quality, and ≤5 indicating good sleep quality (Buysse et al., 1989). The validity and reliability of the questionnaire have been proven in Iranian elderly (Farrahi Moghaddam et al., 2012; Chehri et al., 2020).

World Health Organization (WHO) disability assessment schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0)

The WHODAS 2.0 was used to measure disability levels in older adults. This instrument has 36 items that encompass the six following domains: 1) Cognition (understanding and communicating; 6 items), 2) Mobility (moving and getting around; 5 items), 3) Self-care (hygiene, dressing, eating, and being around people; 4 items), 4) Getting along (interacting with people; 5 items), 5) Life activities (domestic responsibilities, leisure, work, and school; 8 items), and 6) Participation (joining in community activities and participating in society; 8 items). The WHODAS 2.0 uses a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from 0 (no difficulty) to 4 (extreme difficulty or total inability). At first, the sum of items’ scores in each domain was determined and then the sum of the scores of all 6 domains was calculated. Finally, the total scores were converted to 0-100 (0=no disability and 100=complete disability). In other words, lower scores represent less disability (Üstün, 2010). The psychometric properties of the Persian version of the questionnaire have been proven (Salehi et al., 2020; Rajeziesfahani et al., 2019). In the present study, the reliability of the WHODAS 2.0 and PSQI were examined using the Cronbach α on 20 hospitalized older adults, and the Cronbach α was 0.78 and 0.85, respectively. These 20 samples were excluded from the final data analysis.

Data analysis

All of the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software, version 26. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and histogram plots were used to test the normality of the data. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and evaluated with chi-square or Fisher exact test. Continuous data were presented as Mean±SD and were compared using the two-sample independent t-test. A binary logistic regression test was used to determine the predictors of sleep quality. Statistically significant variables in univariate analysis were included in the regression model. The statistical significance level was considered at P<0.05.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics, sleep quality, and disability

The Mean±SD age of the participants was 69±3.63 years, and the majority of them (50.7%) were women, married (81.7%), unemployed (83.3%), and had high school education (60%). The Mean±SD total disability score was 32.36±9.2. The Mean±SD PSQI score was 6.12±2.99 and 50% of the older adults had poor sleep quality (PSQI >5). The highest disability score of the elderly was reported in the life activities domain (38.23±14.63) and the lowest disability score was reported in the participation domain (12.3±19.91). Of the 300 elderly examined, 43(14.3%) had mild disability, 240(80%) had moderate disability, and 17(5.6%) had severe/very severe disability. The Mean±SD burden of comorbidities was 1.15 (0.37) (Table 1).

Univariate analysis results

In univariate analysis, there was a significant relationship between sleep quality and gender, education, smoking, drug use, co-morbidities, and disability. Male gender (P<0.049), lower education (P<0.025), smoking (P<0.019), non-opioid analgesics (P<0.006), more comorbidities (P<0.009), and higher disability scores (P<0.001) were associated with poor sleep quality. No significant relationship was found between age, marital status, employment, duration of hospitalization, and sleep quality (Table 1).

In the multivariate analysis, there was a statistically significant relationship between the burden of comorbidity and the level of disability with poor sleep quality. Accordingly, more burden of comorbidity increased the chance of experiencing poor sleep quality in older adults to the extent of 2.078 times (odd ratio [OR]=2.078, P<0.044). Also, a higher disability score increased the chance of experiencing poor sleep quality in older adults to the extent of 1.044 (P<0.004, OR=1.044; Table 2). Contrary to univariate analysis (Table 1), in the multiple regression model, no significant relationship was found between gender, education, smoking, non-opioid analgesics, and sleep quality of hospitalized older patients (Table 2).

Discussion

Sleep quality is an important issue in hospitalized older people and is affected by several factors. The current study determined the predictive role of disability and comorbidities in the sleep quality of hospitalized elderly patients.

The findings of the present study showed that half of the hospitalized older adults have suffered from poor sleep quality which is in line with the results of Papi et al.’s study on older adults in daycare centers (Papi et al., 2019). A systematic review study also reported that (70%) of Iranian older adults did not have desirable sleep quality (Mortazavi et al., 2021). Contrary to the present study results, Zhang et al. (2020) reported that only (21%) of the older adults suffered from poor sleep quality. They attributed the low prevalence to the definition of poor sleep quality in their study (PSQI >7 vs PSQI >5 recommended by the PSQI developer).

People who are admitted to the hospital usually suffer from disorders such as daytime sleepiness, sleep-wake cycle disruption, and changes in the amount of melatonin hormone secretion due to being confined to bed. Also, hospitalization can be associated with poor sleep quality and reduced sleep duration due to various diseases, stressful conditions, or changes in the sleeping environment (Kulpatcharapong et al., 2020).

In this study, the comorbidities positively predicted poor sleep quality among inpatient older adults which was consistent with the findings of earlier research (Idalino et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2020; Chung et al., 2023; Muhammad et al., 2023). Comorbidities can lead to problems such as insomnia, reduced sleep duration, difficulty breathing during sleep, snoring, and restless legs. These conditions may affect the quality of sleep and cause sleepiness during the day (Appleton et al., 2018). Some chronic diseases may cause changes in the brain regions and neurotransmitters that control sleep. Also, the drugs used to manage comorbidities affect sleep quality (Muhammad et al., 2023). Psychological distress and anxiety associated with comorbidities, including economic burden (Larkin et al., 2021), destructive effects on family relationships and social interactions, and experiencing more negative and stressful life events can lead to the development and exacerbation of sleep problems (Ren et al., 2021; Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al., 2021; Muhammad et al., 2023). On the other hand, Idalino et al. showed that elderly people with sleep problems had a higher chance of developing chronic conditions. They stated that there may be a bidirectional relationship between chronic conditions and sleep quality (Idalino et al., 2023). In contrast to the current study, a prior study showed that there has been no relationship between comorbidities and sleep quality in hospitalized elderly people (Kulpatcharapong et al., 2020). Therefore, early identification and optimizing the management of comorbidities, especially by implementing non-pharmacological interventions, awareness of side effects of medications that aggravate sleep problems, and emphasis on safe nursing care in hospitalized older adults seem necessary to improve the sleep quality of this group (Mc Carthy, 2021; Rashvand et al., 2016).

A previous study suggests that multiple comorbidities and clinical conditions are key elements that should be addressed in the relationship between sleep quality and disability in older adults (Oliveira et al., 2022). In the present study, the highest level of disability was related to the domains of life activities and mobility, and the lowest level of disability was related to the participation domain. In a previous study, the highest level of disability was reported in the domains of life activities and mobility, and the lowest level of disability was related to the self-care domain (Adib-Hajbaghery & Akbari, 2009). In another study, the highest level of disability was reported in the domain of interacting with people and mobility (Ghasemi et al., 2022). The discrepancy in the findings of the studies can be attributed to the differences between the questionnaires, the study setting, and the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

Moreover, our research found a significant positive relationship between disability and sleep quality in inpatient older adults. This finding was similar to the previous studies (Arakaki et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2022; Chien & Chen, 2015). In support of the present study, Mazzotti et al. found that higher levels of disability in older adults have reduced sleep quality and ability to perform daily activities (Mazzotti et al., 2012). Older persons with poor sleep quality suffer fatigue, sleepiness, and lack of concentration during the day. This may reduce their ability to perform life activities (Safa et al., 2015). A prior study reported that older adults with a healthier aging process were able to create more regularity in their sleep patterns, which may have a positive effect on their physical ability (Friedman et al., 2019). Yang et al. suggested that there may be a bidirectional causal relationship between disability and sleep quality in the elderly. Poor sleep quality may hurt physical performance by causing mental fatigue. Also, older persons with moderate and severe disabilities stay longer in bed, which can increase sleep duration and impair sleep quality (Yang et al., 2023). A review study showed that lack of physical activity affects the quantity and quality of sleep in Iranian older adults. Physical activity increases energy consumption and improves sleep quality by endocrine secretions (Mortazavi et al., 2021). Physical activity relieves stress and is associated with good sleep quality in older adults. Encouraging the elderly to exercise and physical activity helps to improve their sleep quality (Song et al., 2020). Strategies to promote healthy sleep, including regular sleep schedules, exercising, and avoiding excessive use of electronic devices before bed, were considered key elements in improving disability associated with sleep disorders in older adults. A healthy and regular sleep pattern may help reduce the risk of developing or worsening chronic conditions in older adults (Idalino et al., 2023; Aliasgharpoor & Eybpoosh, 2011).

Conclusion

The present study added to the existing knowledge regarding the predictors of sleep quality in older adults. Half of the hospitalized older adults had poor sleep quality in our study. Comorbidities and disability were the most important predictors of sleep quality in hospitalized older adults. To promote sleep quality, healthcare providers should educate older adults to report different degrees of disability and symptoms of comorbidities immediately. Also, monitoring older adults for comorbidities and disabilities seems necessary. It is essential to design and implement interventional studies to investigate the effect of physical activity and exercise on sleep quality and disability levels among older adults. Moreover, it is important to identify possible mechanisms (mediating factors) of how comorbidities and disabilities are associated with sleep quality in the older population.

Study limitations

The strength of the present study was the multicenter sampling that increased the generalizability of the findings. However, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits the ability to determine causality. It is suggested that future studies be conducted with a longitudinal design to more clearly understand the predictors of sleep quality in hospitalized older adults. Also, self-reported measurement of sleep quality did not allow objective assessment of sleep quality. It is suggested that future studies use objective methods of sleep quality assessment such as polysomnography.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran (Code IR.QUMS.REC.1402.033). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants after explaining the purpose of the study and ensuring confidentiality and anonymity.

Funding

The current article was taken from a research proposal (No.: 401000095) and it was financially supported by Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, statistical analysis, and supervision: Maryam Momeni and Farnoosh Rashvand; Data collection: Fatemeh Safari Alamuti and Neda Shahsavari; Writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude for the cooperation of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, hospital officials, and elderly people participating in the study.

References

Adib-Hajbaghery, M. & Akbari, H., 2009. [The severity of old age disability and its related factors (Persian)]. Feyz Medical Sciences Journal, 13(3), pp. 225-34. [Link]

Aliabadi, S., et al., 2017. Sleep quality and its contributing factors among elderly people: A descriptive-analytical study. Modern Care Journal, 14(1), pp. e64493. [DOI:10.5812/modernc.64493]

Aliasgharpoor, M. & Eybpoosh, S., 2011. [Quality of sleep and its correlating factors in residents of Kahrizak nursing home (Persian)]. Nursing and Midwifery Journal, 9(5), pp. 1-10. [Link]

Appleton, S. L., et al., 2018. Prevalence and comorbidity of sleep conditions in Australian adults: 2016 Sleep Health Foundation national survey. Sleep Health, 4(1), pp. 13–19. [DOI:10.1016/j.sleh.2017.10.006] [PMID]

Arakaki, F. H., et al., 2022. Is physical inactivity or sitting time associated with insomnia in older men? A cross-sectional study. Sleep Epidemiology, 2, pp. 100023. [DOI:10.1016/j.sleepe.2022.100023]

Buysse, D. J., et al., 1989. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), pp. 193–213. [DOI:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4] [PMID]

Charlson, M., et al., 1994. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 47(11), pp. 1245–51.[DOI:10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5] [PMID]

Chehri, A., et al., 2020. Validation of the Persian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in elderly population. Sleep Science (Sao Paulo, Brazil), 13(2), pp. 119–24. [PMID]

Chiang, G. S. H., et al., 2018. Determinants of poor sleep quality in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia and hypertension in Singapore. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 19(6), pp. 610–5. [DOI:10.1017/S146342361800018X] [PMID]

Chien, M. Y. & Chen, H. C., 2015. Poor sleep quality is independently associated with physical disability in older adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(3), pp. 225–32. [DOI:10.5664/jcsm.4532] [PMID]

Chung, M. H., et al., 2023. Relationship between traits and sleep quality of hospitalized elderly patients and sleep quality of family caregivers. Nursing Open, 10(7), pp. 4384–94. [DOI:10.1002/nop2.1680] [PMID]

Davodi Boroujerdi, Q., et al., 2020. [Investigating factors affecting sleep quality in the elderly suffering from coronary artery diseasee (Persian)]. Research in Medicine, 44(4), pp. 594-9. [Link]

Farrahi Moghaddam, J., et al., 2012. Reliability and validity of the Persian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-P). Sleep and Breathing, 16(1), pp. 79–82. [DOI:10.1007/s11325-010-0478-5] [PMID]

Friedman, S. M., et al., 2019. Healthy aging: American Geriatrics Society white paper executive summary. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(1), pp. 17–20. [DOI:10.1111/jgs.15644] [PMID]

Ghasemi, Z., et al., 2022. Disability among older adults residing in Poldasht, Iran in 2018: The role of social aupport as a protective factor. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 20(4), pp. 481-90.[DOI:10.32598/irj.20.4.825.3]

Gonzalez-Gonzalez, A. I., et al., 2021. Everyday lives of middle-aged persons living with multimorbidity: Protocol of a mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Open, 11(12), pp. e050990.[DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050990] [PMID]

Hosseini, R. S., et al., 2020. Validity and reliability of Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) among Iranian community-dwelling older adults. Acta Facultatis Medicae Naissensis, 37, pp. 160-70. [DOI:10.5937/afmnai2002160H]

HU, W., et al., 2022. The role of depression and physical activity in the association of between sleep quality, and duration with and health-related quality of life among the elderly: A UK Biobank cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), pp. 338. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-022-03047-x] [PMID]

Idalino, S. C. C., et al., 2023. Association between sleep problems and multimorbidity patterns in older adults. BMC Public Health, 23(1), pp. 978. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-023-15965-5] [PMID]

Kulpatcharapong, S., et al., 2020. Sleep quality of hospitalized patients, contributing factors, and prevalence of associated disorders. Sleep Disorders, 2020, pp. 8518396.[DOI:10.1155/2020/8518396] [PMID]

Larkin, J., et al., 2021. The experience of financial burden for people with multimorbidity: A systematic review of qualitative research. Health Expectations, 24(2), pp. 282–95. [DOI:10.1111/hex.13166] [PMID]

Lee, Y. H., et al., 2022. Socio-demographic and behavioural factors associated with status change of sleep quality and duration among Chinese older adults. Ageing & Society, 42(9), pp. 2206-23. [DOI:10.1017/S0144686X21000015]

Luo, M., et al., 2024. Sleep duration and functional disability among Chinese older adults: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Aging, 7, pp. e53548. [DOI:10.2196/53548] [PMID]

Mayfield, K. E., Clark, K. C. & Anderson, R. K., 2023. Sleep quality and disability for custodial grandparents caregivers in the southern United States. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 9, pp. 23337214231163028. [DOI:10.1177/23337214231163028] [PMID]

Mazzotti, D. R., et al., 2012. Prevalence and correlates for sleep complaints in older adults in low and middle income countries: a 10/66 Dementia Research Group study. Sleep Medicine, 13(6), pp. 697–702. [DOI:10.1016/j.sleep.2012.02.009] [PMID]

Mc Carthy C. E., 2021. Sleep disturbance, sleep disorders and co-morbidities in the care of the older person. Medical Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 9(2), pp. 31. [DOI:10.3390/medsci9020031] [PMID]

Mortazavi, S. S., 2021. [Negative factors affecting the sleep quality of the elderly in Iran: A systematic review (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation, 22(2), pp. 132-53. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.22.2.3011.1]

Muhammad, T., Meher, T. & Siddiqui, L. A., 2023. Mediation of the association between multi-morbidity and sleep problems by pain and depressive symptoms among older adults: Evidence from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India, wave-1. Plos One, 18(2), pp. e0281500. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0281500] [PMID]

Oliveira, S. D., et al., 2022. Sleep quality predicts functional disability in older adults with low back pain: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(11), pp. 2374–81.[DOI:10.1177/07334648221113500] [PMID]

Papi, S., et al., 2019. [Determining the prevalence of sleep disorder and its predictors among elderly residents of nursing homes of Ahvaz city in 2017 (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Ageing, 13 (5) , pp. 576-87. [DOI:10.32598/SIJA.13.Special-Issue.576]

Rajeziesfahani, S., et al., 2019. Validity of the 36-item Persian (Farsi) version of the world health organization disability assessment schedule (WHODAS) 2.0. International Journal of Mental Health, 48(1), pp. 14-39. [DOI:10.1080/00207411.2019.1568172]

Rashvand, F., et al., 2016. Iranian nurses perspectives on assessment of safe care: An exploratory study. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(3), pp. 417–26. [DOI:10.1111/jonm.12338] [PMID]

Ren, Z., 2021. Associations of negative life events and coping styles with sleep quality among Chinese adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 26(1), pp. 85. [DOI:10.1186/s12199-021-01007-2] [PMID]

Safa, A., Adib-Hajbaghery, M. & Fazel-Darbandi, A. R., 2015. [The relationship between sleep quality and quality of life in older adults (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 3(3), pp. 53-62. [Link]

Salehi, R., et al., 2020. Validity and reliability of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 36-Item Persian version for persons with multiple sclerosis. Korean Journal of Family Medicine, 41(3), pp. 195–201. [DOI:10.4082/kjfm.18.0155] [PMID]

Song, D., et al., 2020. Correlates of sleep disturbance among older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), pp. 4862. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17134862] [PMID]

Suzuki, K., Miyamoto, M. & Hirata, K., et al., 2017. Sleep disorders in the elderly: Diagnosis and management. Journal of General and Family Medicine, 18(2), pp. 61–71. [DOI:10.1002/jgf2.27] [PMID]

World Health Organization., 2010. Measuring health and disability: Manual for WHO disability assessment schedule WHODAS 2.0. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Link]

Vafaei, Z., et al., 2014. [Prevalence of disability and relevant risk factors in elderly dwellers in Isfahan Province-2012 (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing, 8(4), pp. 32-40. [Link]

Wang, P., et al., 2020. Prevalence and associated factors of poor sleep quality among Chinese older adults living in a rural area: A population-based study. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, pp. 125-31. [DOI:10.1007/s40520-019-01171-0] [PMID]

Yang, S., et al., 2023. The relationship between sleep status and activity of daily living: Based on China Hainan centenarians cohort study. BMC Geriatrics, 23(1), pp. 796. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-023-04480-2] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2024/05/21 | Accepted: 2024/11/5 | Published: 2025/02/1

Received: 2024/05/21 | Accepted: 2024/11/5 | Published: 2025/02/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |